Out of Control

A former Big Green basketball player looks back on well-intentioned drug treatments that cost him a spot on the team.

Mar/Apr 2005 Lance Roberts ’66A former Big Green basketball player looks back on well-intentioned drug treatments that cost him a spot on the team.

Mar/Apr 2005 Lance Roberts ’66A former Big Green basketball player looks back on well-intentioned drug treatments that cost him a spot on the team.

IT ALL CAME APART FOR ME IN Indiana after a Dartmouth game at Pur- due—just before Christmas 1963, during a holiday tour through the Midwest. I was close enough to my hometown to be able to play in front of family and friends who had followed myall-state high school bas- ketball career in Illinois. I was intent on showing them I still had it.

Our road trip had started against Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where I played with my left leg wrapped in elastic from ankle to thigh. I was coming off an injury from playing touch football on the Green on a beautiful fall day. We were a young team that had showed a lot of promise, but—as usualweld been creamed by Marquette. I'd ended the game unable to get airborne for a last-second lay-up and had left the court to the jeers of the crowd. I was also in trouble with Coach Doggie Julian—a first—for wearing a sweater my mother had knitted for me while traveling rather than the coat and tie he required.

Purdue would be different, I thought. I felt strong and could again push off my leg. I was going to start and guard some 7-footer. My folks would be there.

I remember several things about that game: I was playing the 7-footer tight, guarding his belt buckle, so to speak. He took a pass at the top of the key, literally stepped over me and went in for the dunk. He hit his elbow on the rim and we both watched the ball rocket out to about midcourt. What a stiff! I ended up playing the game of my career, scoring more than 20 points only to watch us lose big again.

I hung back from going into the locker room, because I felt crushed to have lost so badly in front of my home crowd. I missed the Midwest, and from personal results saw that I could play Big Ten basketball. When I entered I heard Coach Julian talking to an alumnus, saying that it wasn't his fault he had such a "bad team." I came around the lockers and looked him square in the eye.

Then I went into the dressing room, where Vic Mair '65, the team captain,was telling everyone that they had tried,which was more important than winning. I threw a punch at Vic that knocked him over the bench before I was held back by others on the team. I had "red-lined!"

Dinner that night with my parents consisted of me trying to make conversation with tears coursing down my cheeks. All I wanted to do was "come

home." The night that was to have been the pinnacle of my career was instead profoundly depressing. I was running out my string with Dartmouth basketball. The leg was not the problem. I was just plain angry at everything and everyone: at my parents for making me go away to a college that embraced football and hockey and chewed up basketball players; at Coach Julian, who I felt was an end-of-the-line hasbeen; at the Division I system that meant if I went home to play at Northwestern, I would lose a year of eligibility. I didn't know how to play feeling angry all the time; most of my career I had been known as "Mr. Cool/The Ice Man." When my high school coach signed me up for a summer league in inner Chicago to toughen me up, I lost a few teeth in the process—but staying cool under pressure was my specialty.

Losing my cool previously had already resulted in technical fouls and—on the road in Worcester, Massachusetts—a police escort out of the Holy Cross gym after I took an opposing player by the feet and sent him cartwheeling into the stands. There also had been good times, such as when I held Senator-to-be Bill Bradley to 35 points in a game against Princeton, and when I enjoyed facing a former teammate and all-state Illinois player as well.

But everything came to a head in practice one day, within a month of the Purdue game, when Julian challenged my attitude and team spirit in front of my teammates.I recall throwing a basketball in his general direction and walking off the court. He wasn't about to keep me on the team after that. I was done—literally and figuratively.

It would have been impossible for me to imagine such an end to my Dartmouth career only a few months earlier, when I'd suffered that touch-football injury. Both Gary Bryson '66 and I were going for a pass, and he was knocked into me hard, with his leg whipping around and catching me above my left knee.

I ended up flat on my back for several weeks in Dicks House with a massive hematoma that wiped out most of the muscle in the front of my thigh. It was as if someone had scooped out a portion of my leg. I was 19 years old and was scheduled to start for the varsity basketball team after a sterling freshman year in which I was the top scorer. We were filled with such promise then: Chris Kinum '66, Neil Castaldo '66 and the others actually had a winning record and were going to do for Dartmouth what Bill Bradley had done for Princeton—put us on the basketball map.

Instead,I was limping around on crutches at Dicks House when a doctor arrived to tell me that the coaching staff wanted to try a new experimental drug on me that showed great promise in developing muscle mass, sol could be ready for the winter tour to the Midwest. They called the drug steroids. This drug and a physical rehab program ought to get me back on my feet, I was told. My family, according to my dad, was never consulted. When I left the team, the steroid treatments ended. So did my emotional outbursts. It didn't occur to me to make any cause-effect connections at the time. Unlike today, steroid use was not a news topic.

I wanted to try out for the basketball team the following year, so I attended an organizational meeting as a potential walk-on. After the meeting Julian pulled me aside and told me he was not going to allow me to play because I was a troublemaker. I was disappointed but resigned. I was responsible for my own behavior after all. Or was I? As things turned out, I went on to play basketball recreationally for another 30 years—without a single incident. Never was I riled.

Recently I tuned into a local talk radio show while driving through Massachusetts on business. The topic was steroid use by athletes. The head of the Major League Baseball union described them as less dangerous than cigarettes. Young athletes spoke of them as a means of getting an edge on competition. Finally, a health care professional who had written numerous books and articles on the topic said that while most athletes on steroids do not experience short-term health problems, there are long-term problems and, for many people, specific side effects, which include aggressive or even violent behavior and mood swings. (Dartmouth steroid researchers Ann Clark and Leslie Henderson made similar observations last year in Neuroscience and Biobehavorial Reviews.)

As I listened to this information, I almost drove my car off the road. For the first time I understood my previously inexplicable mood swings and violent outbursts. Even knowing the "why," however, has not kept me from wondering all too often what might have been if I had not been administered steroids and had not reacted as I did.

I attempted to get my medical records from Dicks House but was told they would have been discarded after seven years. I wrote to President Jim Wright, hoping for some response that would bring closure after all these years, but received instead a letter expressing relief there had been no permanent damage to me as a result of the treatments.

There is little comfort in knowing that today athletes and doctors can make more informed choices. I wish that had been the case at Dartmouth when I was there.

Losing my cool earlier had already resulted in technical fouls and a police escort out of the Holy Cross gym.

LANCE ROBERTS lives in Bedford, NewHampshire, where he is a principal in the investment-advisory firm Advisors Capital Resource.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

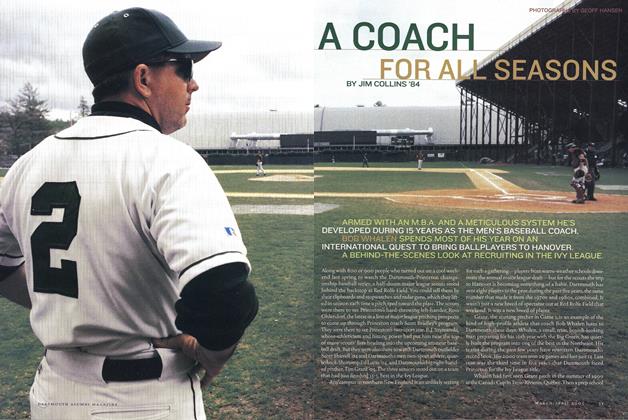

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

March | April 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

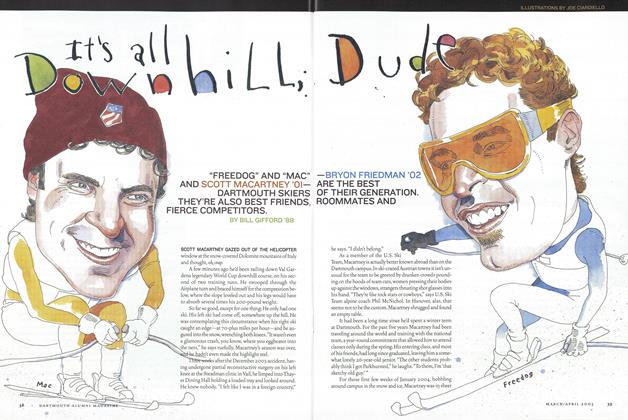

FeatureIt’s All Downhill, Dude

March | April 2005 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

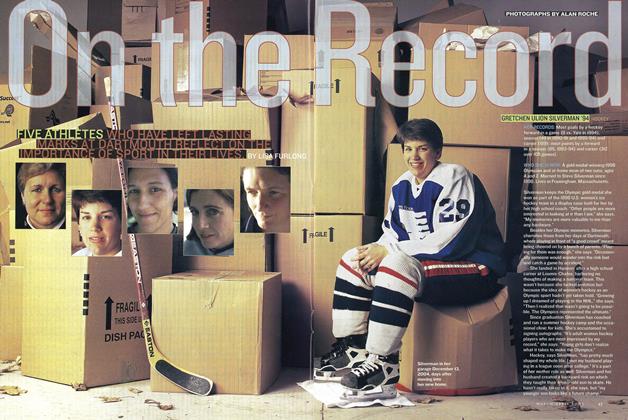

FeatureOn the Record

March | April 2005 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2005 By Gray Mercer '83 -

NEWS ANALYSIS

NEWS ANALYSISFraming the Letter

March | April 2005 By Brad Parks ’96

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLiving Room Learning

Mar/Apr 2008 By Jane Varner Malhotra '90 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

MAY 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryAwakening

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JOE GLEASON ’77, JOE GLEASON ’77 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThere and Back Again

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By MARTY JACOBS ’82 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOver the Hill?

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By MIKE STANITSKI ’92 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryThe Evolved Eater

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By NICK TARANTO ’06