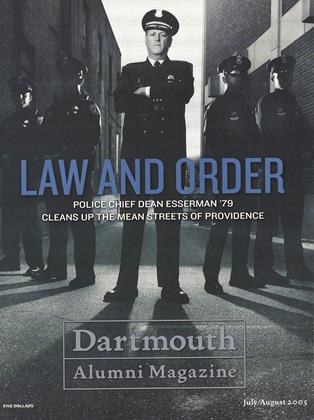

Police Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July/August 2005 DIRK OLIN ’81Police Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence DIRK OLIN ’81 July/August 2005

Police chief Dean Esserman steers his black SUV through the crunching slush of Providence, Rhode Island, on a starless night in Janurary. Across the street from an abandoned laundromat on Federal Hill, he pulls over and points at the dimly lit storefront. "You wouldn't know it to look at it, but that was the headquarters of the Patriarca family, when the mob ran roughshod over this city," he says. "The old man used to sit right in there. For New England, this was the home of the mob. And the mob became city hall."

Esserman's summation of public corruption in Providence is no hyperbole. But the mob wasn't his big problem when he took over the police department in 2003. The feds had cleaned up much of the mafia there during the 1980s and 19905. The new chief had a tougher task: cleaning up the department itself.

Mayor David Cicilline, who hired Esserman, had succeeded Vincent A. "Buddy" Cianci Jr., who was convicted in 2002 on federal charges of racketeering. The cops—known as "Buddy's Boys" for their participation in his culture of cronyism—were in disarray. Bribery to fix exams was widespread among both aspirants to the police academy and cops seeking promotion. The local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union had to sue to force departmental compliance with a state program to cure racial profiling. On the streets, crime was rampant; in the department, sloth was viral: "The department had been a king's army for a generation," recalls the chief. "You could purchase your way in, so for every two or three good academy students or cops, there'd be one who was rotten. At the first three murders I went to, no chief of detectives showed up. And senior officers weren't showing up when other officers were wounded." The decrepitude had attracted national media attention. "Grime dropped across America in the 19905, but the 1990s nev- er happened here," says Esserman. "The mayor asked me what had to happen first. I said the first thing needed was moral outrage. They were burying one or two children a month here."

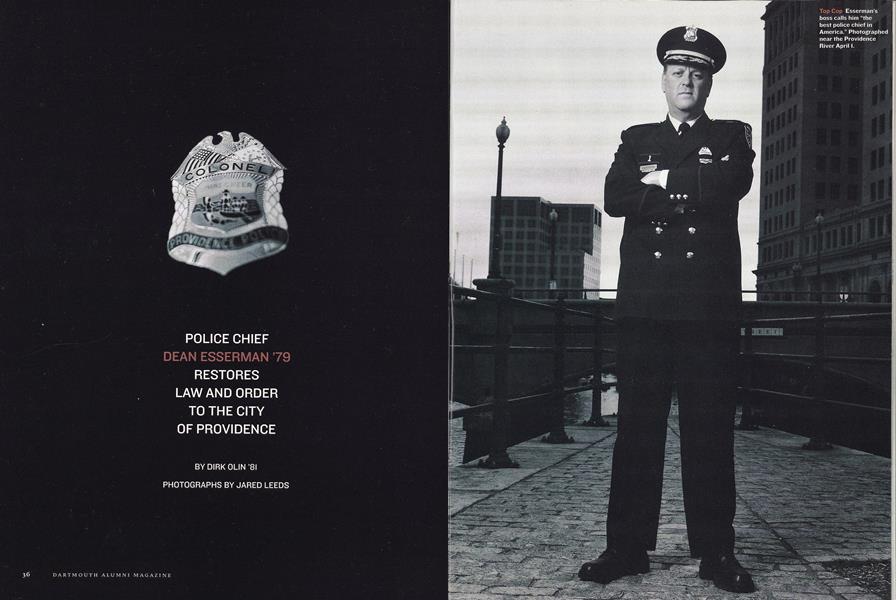

In just two years the chief has cleaned the Augean stables. His internal department reforms and promotion of "social justice" and "community policing" have won him plaudits from business and civil libertarians alike.This January marked the second straight year that the chief could announce a double-digit drop in crime. And the mayor, his boss, calls Esserman "the best police chief in America." This, from a former Dartmouth premed?

SOMEWHAT UNWITTINGLY, ESSERMAN HAD STEPPED ONTO THE PATH that would lead to his current post long before he graduated from Dartmouth. He grew up on the Upper East Side of New York. His father was personal physician to authors Tom Wolfe and Isaac Asimov. His mother was a child psychologist. When he was 12, a pair of bullies burned him with a cigarette and stole his bike. He told his mother. She said, "Run at me." He did, and she flipped him over her shoulder. He was soon taking judo lessons himself and earned a first-degree black belt.

Although that and other experiences instilled what he calls a formative anger, Esserman's outlook was tempered by his family's annual summer trips to developing countries—Guatemala, Ethiopia, China—to provide medical aid for the poor. At the Ethical Culture Society school that he attended during adolescence, Esserman applied to work on an ambulance corps, which brought him into frequent contact with patrol cops. He entered Dartmouth as a history major with an eye toward medical school, and he was still moving in that direction during the summer after his sophomore year when he took an off-term internship offered by Dartmouth Medical School. Under the guidance of then-dean Gregory Prince and Dr. Thomas Almy, he created a medical rescue unit for the New York transit cops. In the summer after his senior year, he deferred enrollment at NYU Law School to accept a one-year position as director of special projects for the transit force. He wrote a grant that received New York City and private funding at a time when the city was too financially strapped to hire badly needed Spanish-speak- ing officers. Esserman brought more than two dozen officers, who sacrificed their vacations, to Hanover for immersion language study under professor John Rassias. "It's one of my greatest memories," Esserman says, "seeing the officers crossing the Green to the Bema for a ceremony as the bells of Baker tolled."

Esserman gradually abandoned the sciences. He became intrigued by how cops were so often pressed into service as first responders in a variety of social situations—landlord disputes, imminent births, domestic altercations, the loss of heat in a tenement. He decided he could enter that world as an attorney. After attending law school he became an assistant prosecutor in Brooklyn, where he first came into contact with his future wife, Gilda Hernandez, who was a paralegal in the office.

Then came the life-changing move. Looking for an intersection of his interests, in 1987 he became general counsel to the New York Transit Police. He began dating Gilda, who had become a detective, and he also became protege to chief William Bratton, who attended Essermans wedding in 1992 and remains a mentor to this day. "I could see from the start he was just this very bright individual with a New York background and someone with one of the most extensive collections of books about police and crime I'd ever seen," recalls Bratton, who is now chief of the Los Angeles Police Department.

Within a couple of years, the assistant chiefs job in New Haven opened, and Esserman landed it. "He was coming in laterally, at a very high level, without having moved up through the ranks," says Bratton. "That's just never done. But he did it the right way—he went through the academy right then, and that helped allay concerns." Esserman reminisces: "I was the highest-ranking rookie ever, but the academy was definitely a tougher road than law school." In New Haven, and a subsequent post running the Metro-North Police in New York, Esserman earned a reputation for cutting crime and invigorating police operations.

Esserman had agreed to raise his wife's son, Rolando, as his own when they wed, and they've since had two of their own, Nellie-June, 12, and Sammy, 8. But when Rolando, now 22, was approaching college age, and with the other two children also attending private school, Esserman took a turn through the private sector. He worked for the security firm that was in charge of preventing the mob from infiltrating reconstruction work at the ruins of the World Trade Center. It was important work, but he was dissatisfied. "It wasn't for me," he says. "I realized this is what I do. I'm a cop."

Still, when Providence's mayor David Cicilline came calling in late 2002, Esserman was careful. He negotiated a package that is extremely lucrative by police standards; with an endowed teaching job as part of the arrangement, he earns just south of $200,000 annually. He also made clear he'd be home every night at 6:30 to be with the kids (before heading back to work after dinner, that is). But, as much as anything, Esserman wanted to be certain that he and Cicilline would be on the same wavelength: "A police chief is only as good as his mayor lets him be," says Esserman.

ESSERMAN'S SMILE IS SLIGHTLY MISCHIEVOUS, A BIT OF A SQUINT that conveys an "I-know-more-about-you-than-you-realize" air. It's the expression of a guy who has found success through the embrace of his calling. But a worldliness lurks behind the twinkle. The kid who got cigarette burns has worked his way through departmental soap operas and media-soaked politicking to get where he is.

The chiefs world was rarely as klieglit as earlier this year when the murder of a Providence detective right in police headquarters garnered national media attention. Even the most disgruntled member of the force could unite with the chief after that incident, but Esserman's longer term campaign to reform the department was not so universally acclaimed. "Right, a lawyer from New York with a Puerto Rican wife has come to town," Esserman recalls with a laugh. "Now you know why I let her start my car in the morning." But it wasn't really his wife or background that unsettled the troops. "They knew I'd come to look for the names on the bathroom wall," he says.

Esserman immediately became übiquitous. The local press captured him making appearances at shooting sites, chatting up cops on the streets, visiting victims in hospitals. Equally important, within months he had replaced the vast majority of the command structure He assigned a senior team, including highly respected members of the homicide unit, to investigate the testing scandal. Training and promotion were made rigorous and transparent.

Esserman is unapologetic. "You have to understand," he says. "I'll never forget one of my first days, when a guy came to ask me if he should fix the tape machine. I said, "What are you talking about?' And it turns out they had a secret taping system right in headquarters!"

smoke inhalation than firefighters? I took from my father and his medical training that cops should follow the Hippocratic oath too. First, do no harm."

And then some. On the night of the windshield tour, a blizzard is coming. Esserman is mostly obsessing about two things: getting the homeless indoors and making sure the public works department would be able to clear the streets. "The cops," he repeats like a mantra, "we're the 24/7 government."

Nor were his subordinates being obsequious when they addressed Esserman as "colonel." It's merely an anachronistic tradition the chief says dates to a predecessor who had assumed the Providence job after holding the military rank as head of the state troopers. (In a state as small as Rhode Island, the urban force is the more powerful, with significantly more personnel.) Indeed, in contradiction of the honorific, Esserman is abjectly non-militaristic True, he wears his chiefs garb well. Preparing for a state trooper ceremony the next morning, he reveals the common police officer s trait of wearing his uniform far more smartly than his (mildly disheveled) civvies. But after the trooper ceremony, his recollection of one speaker's allusion to "the war on crime" makes him cringe as we drive back to his office. "How," he asks rhetorically, "can you declare war on your own citizens?"

Pretty lefty for a cop. And yet Steven Brown, executive director of the local ACLU, ultimately gives Esserman a mixed report card. "He's had a very positive impact on the department and its professionalism. But it hasn't all been roses. We sued his predecessor over compliance with the program to compile statistics about traffic stops to deal with racial profiling. But in fact, the city has continued its appeal of that suit, and that's troubled us. The other big one was that we learned the police had obtained $100,000 in homeland security funds to have officers receive training in what was euphemistically called 'handling' protests and civil actions. This was right around the time they were putting protesters in pens at the Boston convention. We found it disturbing that of all the training they could get, this is the one they chose."

On the profiling appeal, Esserman is dismissive. "That's about lawyers getting fees—and that's an issue decided by the mayor in consultation with the city lawyer." And the protestor control grant? "He's got it just plain wrong—Boston was where they did it right. There were T-shirts everywhere that said, 'We take no prisoners,' because they made no arrests. That was a model, not a problem."

THOSE FAMILIAR WITH IMAGES OF ROLL CALLS FROM TV COP SHOWS would have been disappointed by the real thing, at least on the night (months before the detective shooting) Esserman provided his guided tour. It was essentially a tedious chant-and-response of patrol car assignments in a cramped, fluorescent-lit room that resembled a community college classroom. No avuncular advice from the sarge. No witty repartee or dark mutterings. No mugshots of hardened fugitives passed around in a foreshadow of some dramatic manhunt. So for what possible reason had the chief dropped by roll call on a frigid January midnight? "I try to make at least one midnight roll call a week," he says. "And now all senior officers put on the uniform at least one night a week."

Chief Bratton might have the explanation here. "There was a time when Dean was probably more attuned to the higher-ups," he says. "But he's learned to focus and manage from the middle down. He's been through a lot of shark-infested waters, and he's matured. That's why I get a lot from him. And that's why a major city department will be knocking on his door someday."

Replies Esserman: "It's true I used to spend a lot of time looking up, but now I focus on the people who do the work. Bill Bratton is one of the greatest teachers I ever had. I used to go on patrol with him where he'd spend his time trying to catch officers—catch them doing something right so he could talk about it. You cannot lead cops unless you love 'em." And his big city aspirations? "I've come to live in the moment. And I've come to realize that making change can be easier than sustaining change, which is more important. If they knock on my door anytime soon, I'm going to say, 'Thank you, but no.'"

If Esserman is still occasionally self-promoting, he's also frequently self-effacing. Perhaps, then, the most meaningful object in Esserman's capacious office overlooking the highway (besides the gazillion family photos) is not the small picture of Baker Tower tucked into his bookshelf. Rather, it's the quote from Atilla the Hun that's taped inside his desk drawer: "Chieftains make great personal sacrifices for the good of their Huns."

Esserman's boss calls him "the best police chief in America." Photographed near the Providence River April I.

A Forci To Reckon With Esserman's no-nonsense manner has led to reforms that are transforming a once-corrupt department and reducing crime.

All In a Day's Work I After the April shooting death of one of his detectives, IB Esserman appeared !■ at a roll-call (right) n and conferred with I other officers (mid- I die) at police head- I quarters. A few days later (far right) H Esserman struggled B to revive a sense H of normalcy within the department.

" You cannot lead cops unless you love 'em," says the chief.

DIRK OLIN is executive director of the Institute of Judicial Studies. Hiswork has appeared in The New York Times, Slate and The American Lawyer, where he is a contributing editor. He lives in Maplewood, New Jersey.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMud, Madras and Madness!

July | August 2005 By Gina Barreca ’79 -

Feature

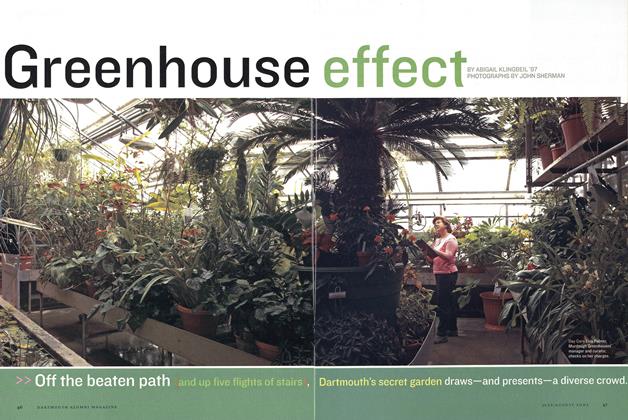

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July | August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80 -

FACULTY

FACULTYLearning Curve

July | August 2005 By James Heffernan -

Sports

SportsGoing the Distance

July | August 2005 By Jennifer Dziura ’00

DIRK OLIN ’81

-

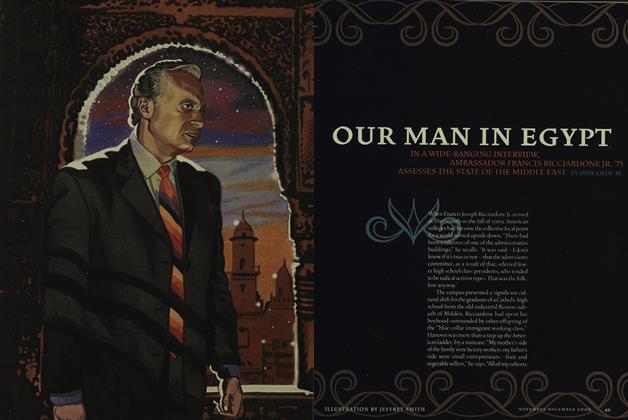

Cover Story

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

Nov/Dec 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

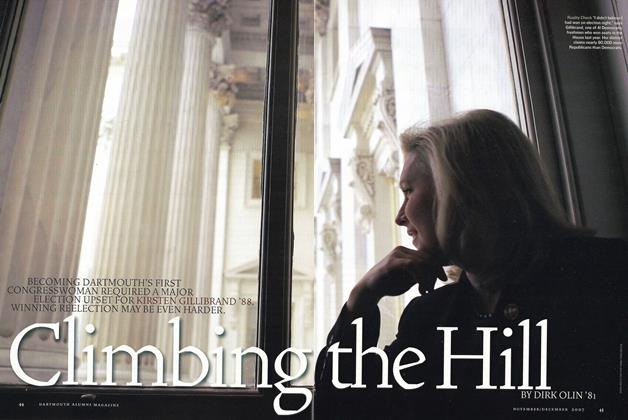

Cover Story

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

Nov/Dec 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

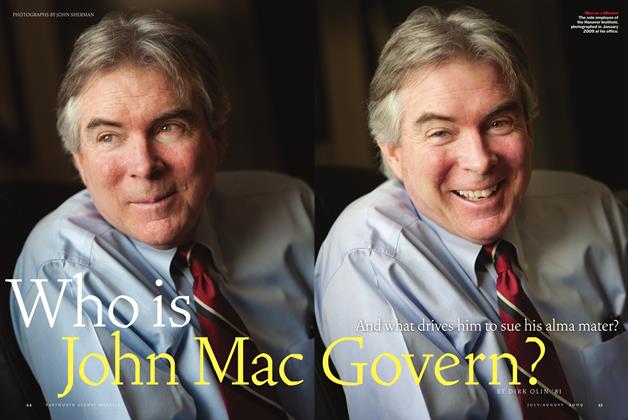

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July/Aug 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Cover Story

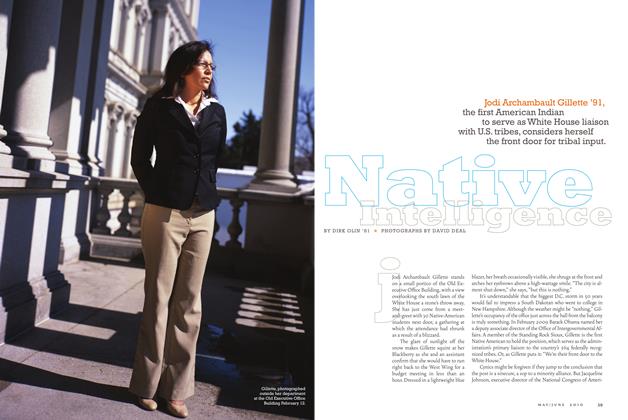

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Article

ArticleSpecial K

MAY | JUNE By Dirk Olin ’81