Seeing and Believing

In a world where digital images aren’t always as they seem, computer science professor Hany Farid is in great demand.

Nov/Dec 2008 Carolyn Kylstra ’08In a world where digital images aren’t always as they seem, computer science professor Hany Farid is in great demand.

Nov/Dec 2008 Carolyn Kylstra ’08In a world where digital images aren't always as they seem, computer science professor Hany Farid is in great demand.

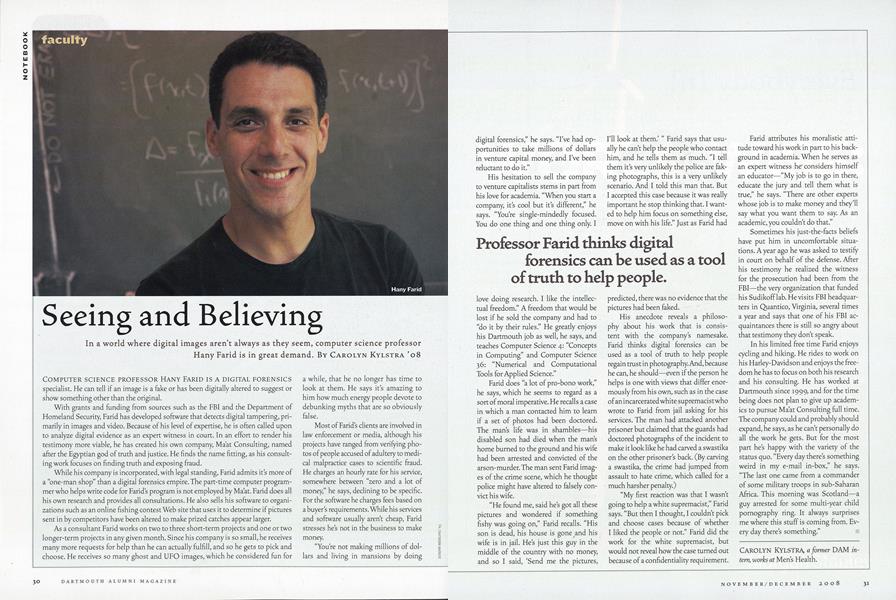

COMPUTER SCIENCE PROFESSOR HANY FARID IS A DIGITAL FORENSICS specialist. He can tell if an image is a fake or has been digitally altered to suggest or show something other than the original.

With grants and funding from sources such as the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, Farid has developed software that detects digital tampering, pri- marily in images and video. Because of his level of expertise, he is often called upon to analyze digital evidence as an expert witness in court. In an effort to render his testimony more viable, he has created his own company, Ma'at Consulting, named after the Egyptian god of truth and justice. He finds the name fitting, as his consult- ing work focuses on finding truth and exposing fraud.

While his company is incorporated, with legal standing, Farid admits it's more of a "one-man shop" than a digital forensics empire. The part-time computer programmer who helps write code for Farid's program is not employed by Ma'at. Farid does all his own research and provides all consultations. He also sells his software to organizations such as an online fishing contest Web site that uses it to determine if pictures sent in by competitors have been altered to make prized catches appear larger.

As a consultant Farid works on two to three short-term projects and one or two longer-term projects in any given month. Since his company is so small, he receives many more requests for help than he can actually fulfill, and so he gets to pick and choose. He receives so many ghost and UFO images, which he considered fun for a while, that he no longer has time to look at them. He says it's amazing to him how much energy people devote to debunking myths that are so obviously false.

Most of Farid's clients are involved in law enforcement or media, although his projects have ranged from verifying photos of people accused of adultery to medical malpractice cases to scientific fraud. He charges an hourly rate for his service, somewhere between "zero and a lot of money," he says, declining to be specific. For the software he charges fees based on a buyers requirements. While his services and software usually aren't cheap, Farid stresses he's not in the business to make money.

"You're not making millions of dollars and living in mansions by doing digital forensics," he says. "I've had opportunities to take millions of dollars in venture capital money, and I've been reluctant to do it."

His hesitation to sell the company to venture capitalists stems in part from his love for academia. "When you start a company, it's cool but it's different," he says. "You're single-mindedly focused. You do one thing and one thing only. I love doing research. I like the intellectual freedom." A freedom that would be lost if he sold the company and had to "do it by their rules." He greatly enjoys his Dartmouth job as well, he says, and teaches Computer Science 4: "Concepts in Computing" and Computer Science 36: "Numerical and Computational Tools for Applied Science."

Farid does "a lot of pro-bono work," he says, which he seems to regard as a sort of moral imperative. He recalls a case in which a man contacted him to learn if a set of photos had been doctored. The mans life was in shambles—his disabled son had died when the mans home burned to the ground and his wife had been arrested and convicted of the arson-murder. The man sent Farid images of the crime scene, which he thought police might have altered to falsely convict his wife.

"He found me, said he's got all these pictures and wondered if something fishy was going on," Farid recalls. "His son is dead, his house is gone and his wife is in jail. He's just this guy in the middle of the country with no money, and so I said, 'Send me the pictures, I'll look at them.' " Farid says that usually he can't help the people who contact him, and he tells them as much. "I tell them it's very unlikely the police are faking photographs, this is a very unlikely scenario. And I told this man that. But I accepted this case because it was really important he stop thinking that. I wanted to help him focus on something else, move on with his life." Just as Farid had predicted, there was no evidence that the pictures had been faked.

His anecdote reveals a philosophy about his work that is consistent with the company's namesake. Farid thinks digital forensics can be used as a tool of truth to help people regain trust in photography. And, because he can, he should—even if the person he helps is one with views that differ enormously from his own, such as in the case of an incarcerated white supremacist who wrote to Farid from jail asking for his services. The man had attacked another prisoner but claimed that the guards had doctored photographs of the incident to make it look like he had carved a swastika on the other prisoner's back. (By carving a swastika, the crime had jumped from assault to hate crime, which called for a much harsher penalty.)

"My first reaction was that I wasn't going to help a white supremacist," Farid says. "But then I thought, I couldn't pick and choose cases because of whether I liked the people or not." Farid did the work for the white supremacist, but would not reveal how the case turned out because of a confidentiality requirement. attributes his moralistic attitude tude toward his work in part to his background in academia. When he serves as an expert witness he' considers himself an educator—"My job is to go in there, educate the jury and tell them what is true," he says. "There are other experts whose job is to make money and they'll say what you want them to say. As an academic, you couldn't do that."

Sometimes his just-the-facts beliefs have put him in uncomfortable situations. A year ago he was asked to testify in court on behalf of the defense. After his testimony he realized the witness for the prosecution had been from the FBI—the very organization that funded his Sudikoff lab. He visits FBI headquarters in Quantico, Virginia, several times a year and says that one of his FBI acquaintances there is still so angry about that testimony they don't speak.

In his limited free time Farid enjoys cycling and hiking. He rides to work on his Harley-Davidson and enjoys the freedom he has to focus on both his research and his consulting. He has worked at Dartmouth since 1999, and for the time being does not plan to give up academics to pursue Ma'at Consulting full time. The company could and probably should expand, he says, as he can't personally do all the work he gets. But for the most part he's happy with the variety of the status quo. "Every day there's something weird in my e-mail in-box," he says. "The last one came from a commander of some military troops in sub-Saharan Africa. This morning was Scotland—a guy arrested for some multi-year child pornography ring. It always surprises me where this stuff is coming from. Every day there's something."

Hany Farid

Professor Farid thinks digital forensics can be used as a tool of truth to help people.

Carolyn Kylstra, a former DAM intern, works at Men's Health.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

November | December 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureOn the Money

November | December 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

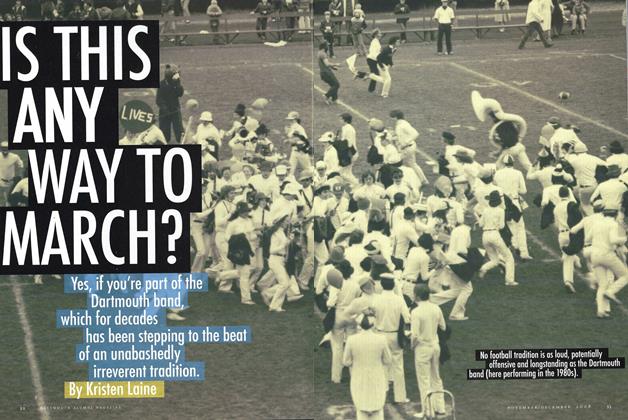

FeatureIs This Any Way To March?

November | December 2008 By Kristen Laine -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

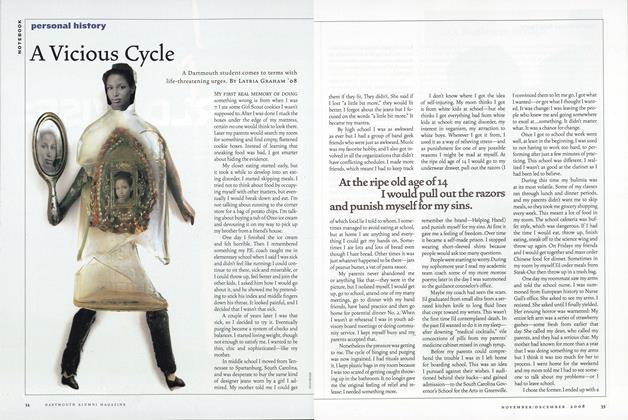

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

November | December 2008 By Latria Graham ’08

Carolyn Kylstra ’08

-

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May/June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticlePlanet Dartmouth

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

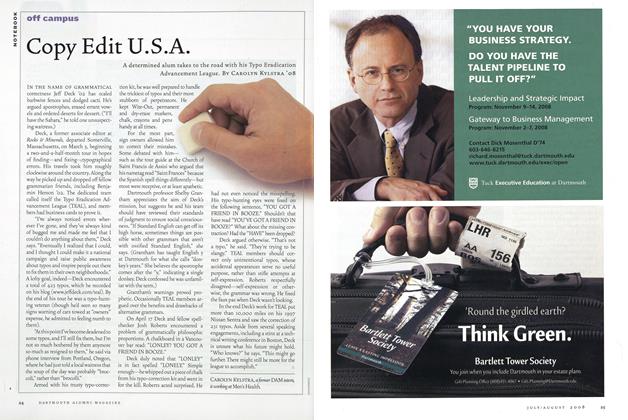

Off Campus

Off CampusCopy Edit U.S.A.

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

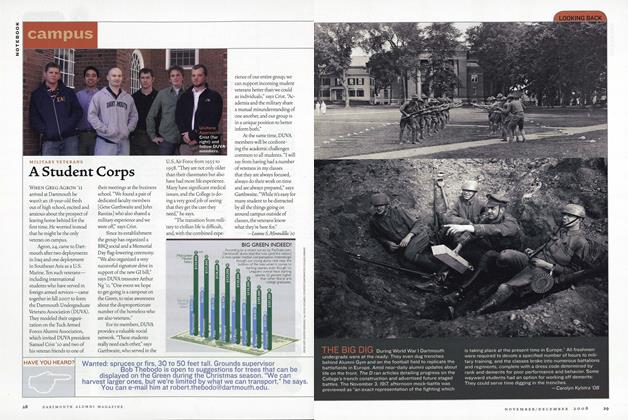

Article

ArticleLOOKING BACK

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

STUDENT LIFE

STUDENT LIFEEverybody In!

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

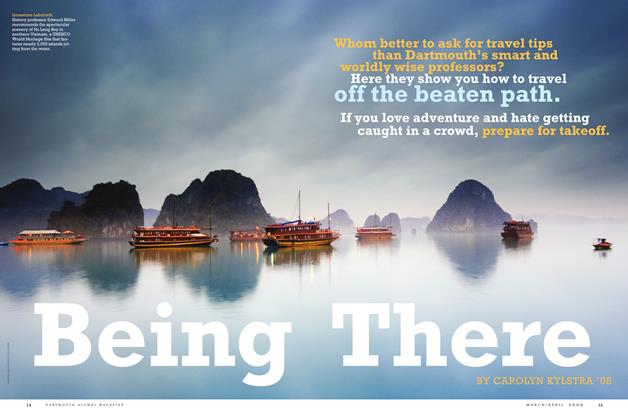

COVER STORY

COVER STORYBeing There

Mar/Apr 2009 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08

FACULTY

-

Faculty

FacultySubject Matter

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 -

FACULTY

FACULTYThe Beat Goes On

Nov/Dec 2011 By Ben Moynihan ’87 -

FACULTY

FACULTYLearning Curve

July/August 2005 By James Heffernan -

FACULTY

FACULTYOut of the Ordinary

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By LAUREN VESPOLI '13 -

FACULTY

FACULTYMore than a Game

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

FACULTY

FACULTYThe Truth Is Out There

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14