The Life of Riley

Long before any hockey fan believed in miracles, Jack Riley ’44 was the sport’s original “America’s Coach.”

July/August 2005 Joe BertagnaLong before any hockey fan believed in miracles, Jack Riley ’44 was the sport’s original “America’s Coach.”

July/August 2005 Joe BertagnaLong before any hockey fan believed in miracles, Jack Riley '44 was the sport's original "America's Coach."

HE IS A GRACIOUS HOST TO VISITORS to his Cape Cod home. The place is not unlike a museum. There are the game action photos from hockey rinks around the world. There are the posed head shots in uniforms, some athletic, some military. There are the framed letters from U.S. presidents and other dignitaries.

"Now just look at this," the 83-year-old legend says, pointing to an outrageous error identifying someone other than him as coach of the 1960 gold medal-winning U.S. Olympic Hockey Team. "Do you believe that? And it's from the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame!"

Before hockey coach Herb Brooks won championships with American kids at the University of Minnesota and won Olympic gold at Lake Placid in 1980, becoming immortalized as "Americas Coach," Riley had already earned the right to that title. But Riley made his mark without the impact of todays mass media and before "Do you believe in miracles?" became a household phrase.

A look at the life of Riley—from childhood in suburban Boston to establishing records at Dartmouth to military heroism to coaching greatness—supports the proposition that it was Riley who was truly 'America's Coach."

Long before his remarkable adult life unfolded, Riley was well prepared for greatness. A native of Med ford, Massachusetts, he grew up in a competitive household with three brothers, two of whom would eventually be enshrined, with Jack, in the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame, the only trio so honored.

Their father, John, performed locally as a singer but it was their mother, Elizabeth, whose influence propelled Jack to his accomplished career. She ran Bostons most fashionable dress shop, Driscoll's, which catered to high society. Anyone who was anyone bought formal wear at Driscoll s.

Young Jacks world was expanded beyond Medford as he regularly accompanied his mother abroad for fashion shows and rubbed elbows with movers and shakers of the time. One such contact was Walter Brown, a leading sportsman of the era, who owned both the Boston Bruins and the Boston Celtics, as well as the Boston Garden. (He once offered Elizabeth a percentage of Celtics ownership in return for wiping out a small debt. She declined.)

Riley's first step onto a bigger stage began when he enrolled at Dartmouth in the fall of 1940. From the start he would be linked with Dick Rondeau '44 and Bill Harrison '44. Together they formed one of college hockeys most productive lines and set numerous Dartmouth records. Each went on to become a head coach at the college level: Riley at West Point, Rondeau at Providence and Harrison at Clarkson.

Part of their lofty place in Dartmouth history stems not only from their individual statistics but also from their role in launching The Streak, the run of 45 games without a loss that four Dartmouth teams assembled from December 23, 1941, to January 5, 1946.

The three were on the Big Green roster when The Streak began with a 5-4 overtime win at Illinois in which Rondeau scored four goals and Riley sat out with two broken fingers. He would eventually return to the lineup in January and participate in 12 of The Streaks first 15 wins. But his first varsity season would ultimately be interrupted by more than aching fingers. A week before the first game of the season Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Returning to Hanover after that early-season trip to Illinois, the young men of Dartmouth had to face the reality thrust upon them by Pearl Harbor. The draft board mailed notices to all eligible young men. Physicals were ordered. Fulfilling hockey dreams seemed doubtful.

Riley's season ended with a handful of games left on the schedule. The three sophomore stars—Riley, Rondeau and Harrison—combined for 101 goals and 83 assists for an amazing 184 points. The goal production accounted for nearly 70 percent of the team output for the season.

While the three stars would each wear the Dartmouth jersey in other seasons, they would never play together again.

From the summer of 1942 to May 1945 Riley prepared for war. His training took him from Squantum to stops in Jacksonville, Atlanta, Corpus Christi and Pensacola until he was ready to enter the Pacific theater. The values learned from athletic competition formed no small part of his training—and proved invaluable through 20 wartime missions in the South Pacific.

Riley's willingness to tell the story of his preparation for war stands in contrast to his reluctance to play up his wartime accomplishments. Says his fellow Indian Squadron member Bob McLaughry 44, "I'm sure Jack downplays all that he did. And perhaps there wasn't anything spectacular or headline-grabbing. But he was reliable and if he went on a mission, he was going to do it right. He was in a number of roles that carried great responsibility with them and he did those jobs well. And that's why many commanders wanted athletes for so many assignments that required discipline."

In January 1946, when Dartmouth hockey tasted defeat for the first time in four years, Riley was being discharged from the Navy and preparing to return to the College—and the top levels of amateur ice hockey.

What followed was an unparalleled Hall-of-Fame string of successes, any one of which would make for another persons career highlight. There he was on the 1948 Olympic team, fresh out of Hanover. Next he served as player-coach of the 1949 U.S. national team. His playing days over, the former Navy pilot began a 36-year coaching career at West Point, overseeing 542 Army victories. And then came an Olympic gold medal with the U.S. team at Squaw Valley, Nevada, in 1960.

He also became the head of college hockeys "First Family." Oldest child Jay played at Harvard and served as an assistant at Cornell and Brown. Sons Mark and Rob were captains at Boston College; Rob followed Jack as head coach at West Point for 18 years and 306 career wins. Son Brian played at Brown, later assisting Rob with the Cadets, and is now in his first season as the new Army head coach. And there is daughter Mary Beth, a female hockey pioneer who played on the early women's teams at St. Lawrence.

Last fall, in Boston Jack Riley entered the Massachusetts Hockey Hall of Fame. For all he has done, it was a belated honor. When Riley stepped to the podium he accepted his hardware with pride and deliberately spoke only of the 1960 Olympic team. Earlier he had pointed out the omission of a gold medal mention in the bio written for the evening's program. He has earned the right to a little mischief in this, his ninth decade. He has served the nation in battle and he has served its youth on the playing fields. He is America's Coach.

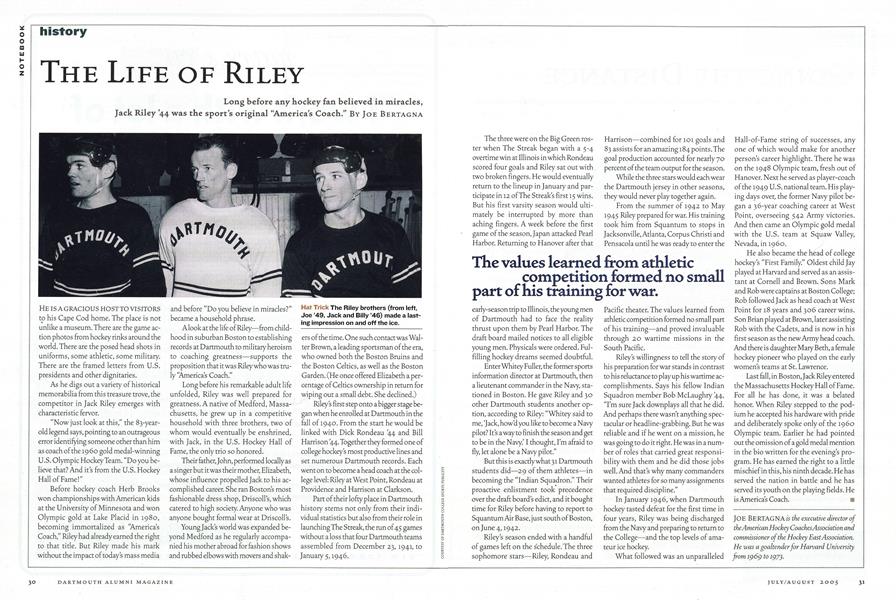

Hat Trick The Riley brothers (from left,Joe '49, Jack and Billy '46) made a lasting impression on and off the ice.

The values learned from athletic competition formed no small part of his training for war.

JOE BERTAGNA is the executive director ofthe American Hockey Coaches Association andcommissioner of the Hockey East Association.He was a goaltender for Harvard Universityfrom 1969 to 1973.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

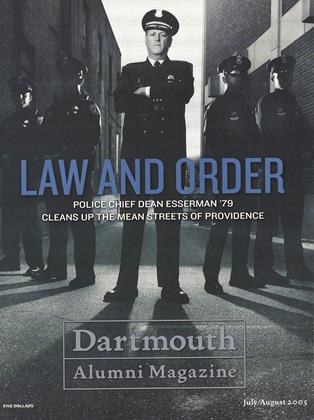

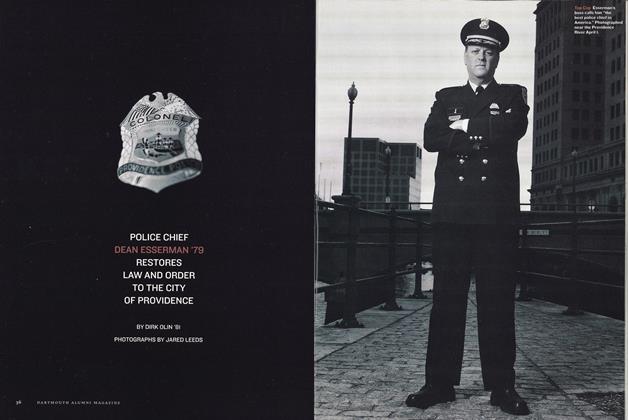

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July | August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureMud, Madras and Madness!

July | August 2005 By Gina Barreca ’79 -

Feature

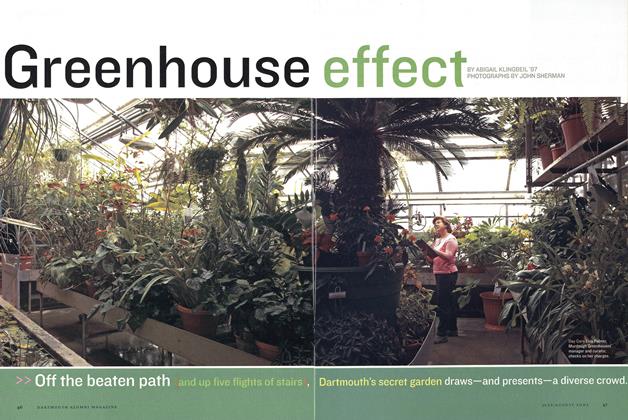

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July | August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80 -

FACULTY

FACULTYLearning Curve

July | August 2005 By James Heffernan

HISTORY

-

HISTORY

HISTORYTies that Bind

May/June 2013 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

HISTORY

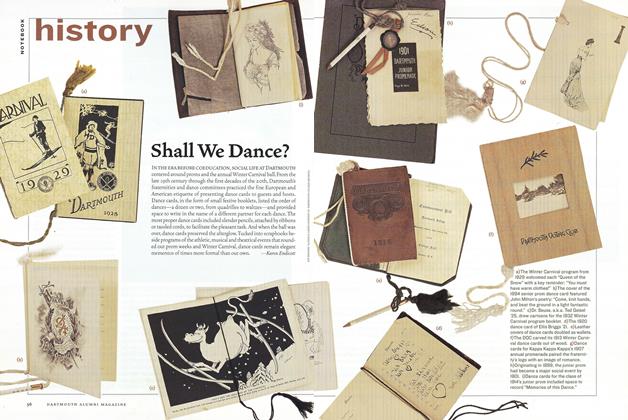

HISTORYShall We Dance?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

History

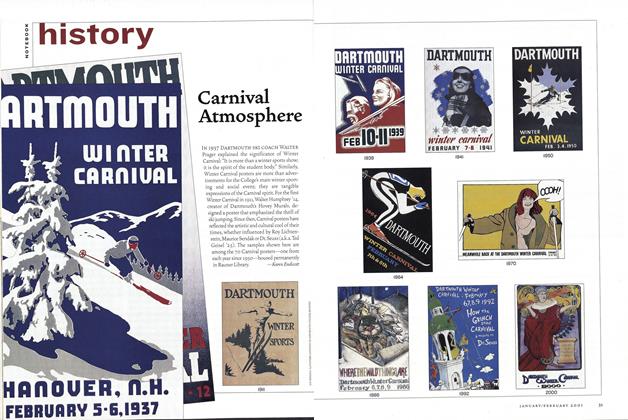

HistoryCarnival Atmosphere

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott -

HISTORY

HISTORYDéjà Vu All Over Again

Mar/Apr 2008 By Marilyn Tobias -

HISTORY

HISTORYA House United

May/June 2011 By Michael Lasser ’57 -

HISTORY

HISTORYDate of Infamy

Nov/Dec 2010 By Takanobu Mitsui ’43