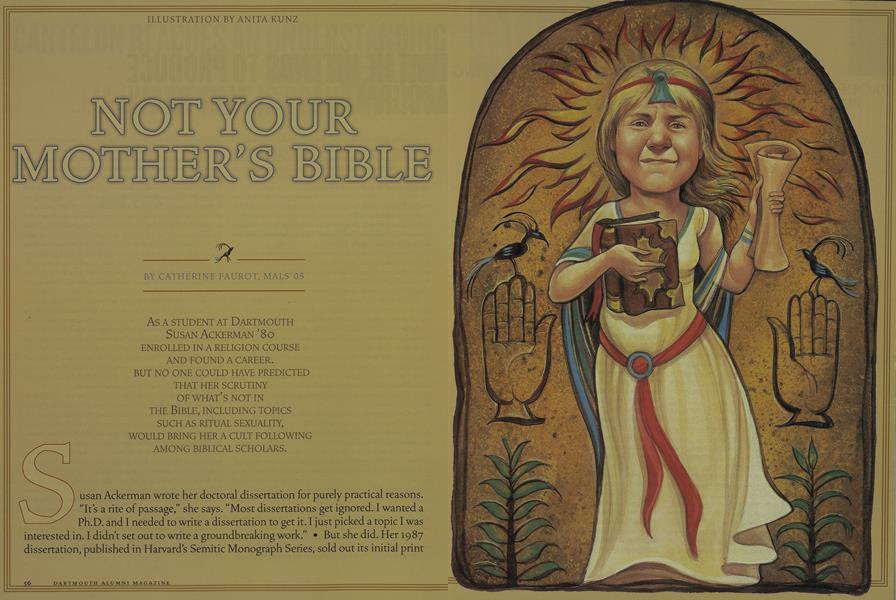

Not Your Mother’s Bible

As a student at Dartmouth Susan Ackerman ’80 enrolled in a religion course and found a career. But no one could have predicted that her scrutiny of what’s not in the bible, including topics such as ritual sexuality, would bring her a cult following among biblical scholars.

Nov/Dec 2006 CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05As a student at Dartmouth Susan Ackerman ’80 enrolled in a religion course and found a career. But no one could have predicted that her scrutiny of what’s not in the bible, including topics such as ritual sexuality, would bring her a cult following among biblical scholars.

Nov/Dec 2006 CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05As A STUDENT AT DARTMOUTH SUSAN ACKERMAN ' 80 ENROLLED IN A RELIGION COURSE AND FOUND A CAREER. BUT NO ONE COULD HAVE PREDICTED THAT HER SCRUTINY OF WHAT'S NOT IN THE BIBLE, INCLUDING TOPICS SUCH AS RITUAL SEXUALITY, WOULD BRING HER A CULT FOLLOWING AMONG BIBLICAL SCHOLARS.

usan Ackerman wrote her doctoral dissertation for purely practical reasons. "Its a rite of passage," she says. "Most dissertations get ignored. I wanted a Ph.D.and I needed to write a dissertation to get it. I just picked a topic I was interested in. I didn't set out to write a groundbreaking work." • But she did. Her 1987 dissertation, published in Harvard's Semitic Monograph Series, sold out its initial print run of 700, and is still in print almost 30 years later.

Ackerman, who earned both a master s of theological studies degree and a doctorate from Harvard in biblical studies, was interested in what she terms "the losers" in an ancient theological battle. The ancient Jewish authors of the Hebrew Bible were the winners, and they present an image of early Judaism that is uniformly monotheistic and rigidly distinct from the religion practiced in neighboring Canaan. What Ackerman found in her research was a profound difference between what the winners were saying and what the early Israelites were actually doing. What they were doing touches on flash points in our culture including ritual sexuality and worship of the divine feminine. Ackermans subsequent work continued to focus on ancient topics that resonate deeply in modern society. Her subsequent books have generated both scholarly impact and a public cult following.

he future biblical scholar grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, with polarized views of religion. Her own family was nonreligious, but she lived in the heart of the Bible Belt. "Little Rock may not have been the buckle of the Belt," says Ackerman, "but it was a place where a classmate could tell me that God created the world in six days and on the seventh created the fossils to test our faith."

Her family, which had once belonged to a Unitarian fellowship, eschewed all religion after she turned 10. Given that Unitarians reject both the divinity of Christ and the concept of the Trinity, Ackerman's tenuous religious affiliation was at odds with the beliefs of her fundamentalist peers. Further, her experience of the Unitarians was primarily as a political group.

"It was basically a front for the Civil Rights movement," she says. "The community revolved around ultra-liberal social activism. We met on Sunday, but were actively planning our next counter sitin. I remember singing 'We Shall Overcome.'"

When her family stopped going to any sort of church, Ackerman was a target for conversion attempts by her classmates. "Prior to coming to Dartmouth my sense of peoples relationship to the Bible was that they either thought it was a fairy tale or that it was literally true," she says. "I understood it as a dichotomy, something that you either believed in or you didn't."

Following her advisors recommendation to explore areas she knew nothing about, Ackerman signed up for Religion 1 in her freshman year. She listened to people talking about the Bible in ways she'd never dreamed of, in challenging and intelligent ways unlike her family's dismissive attitude or her high school classmates' literal interpretation. "The field of religious studies is not about be- lief," she says. "But it understands that for the community of believers religion is a profound, complex and complete expression of beliefs. That first course was revelatory for me, and the study of religion has never ceased to be exciting to me."

While finding a major fell into place fairly effortlessly, not all of Ackermans transitions at Dartmouth went so smoothly. She came to a campus just four years into coeducation. "Dartmouth was an intensely male place," says Ackerman. "There were three guys for every woman. It was an historically male college steeped in allmale traditions. The alumni body was virtually all male and it was a big deal for the alumni to come back." She laughs. "There were a lot of portraits of dead men, and it was hard to even find women's bathrooms."

Coming from the South, Ackerman also found Dartmouth's social scene jarring. "I didn't even know what a prep school was," she says. "The only private high schools in Arkansas were Catholic. During orientation week I had no answer to the question, 'Where did you prep?' " To make matters worse, she disliked the fraternity system.

Although she made accommodations to fit in—including shedding her Southern accent—Ackerman eventually retreated from Dartmouth's social life and devoted herself to her academic work. She also spent significant portions of time away from campus. She studied in London her junior fall term and didn't return to campus until the following fall. (She had taken enough extra classes that she still graduated with more than the required number of credits.)

When Ackerman graduated with a major in religious studies she was determined to pursue biblical studies at Harvard. To celebrate graduating she plunged right into a summer intensive course in Hebrew—a year-long course completed in eight weeks. Half her fellow students at the Harvard Divinity School were studying for the ministry in a progressive political atmosphere that contrasted sharply with the Southern Baptists of her childhood. She was in the other half of the student body, immersed in language studies.

Ackerman took three years of Hebrew, two years of Greek and one year of Aramaic and taught herself Latin—on top of the French and German she brought with her. And this was before she began her doctoral studies, where she added three years of Akkadian, one year of Ugaritic and a final year of miscellaneous Semitic languages.

It was the Ugaritic that started the controversy.

"Ugaritic is a Canaanite language, and my professor and I were most interested in Ugaritic mythology," she says. "As I read the myths it became clear that these texts are parallel to huge parts of the Bible. The biblical tradition says that Israel stood opposed to everything Canaanite, but in a lot of fundamental ways the ancient Israelites couldn't look more Canaanite, including the worship of other deities and fertility rituals."

The evidence that Ackerman and colleagues were unearthing showed ritual devotion to deities other than Yahweh: Both the Bible and archeological evidence suggest that Yahweh was worshiped along with a female consort called Asherah. Other ritual practices offered devotion to the god Tammuz and the goddess known in the Bible as the Queen of Heaven, who is probably a composite of Ishtar and Astarte, two other Near Eastern goddesses. The biblical writers present these religious practices as occasional aberrations, when in fact they were normative for centuries before being eliminated.

The process of elimination was so complete that the biblical record contains little information about these religious practices, says Ackerman, who compares the biblical editing process to the modern political practice of "spinning" public opinion. "I was interested in what was actually happening in religious practice, not what the spin doctors said was going on," she says. The official term for those early spin doctors is "Deuteronomistic redactors," after the Book of Deuteronomy, one of several books in the Hebrew Bible that chronicles a series of religious reforms. Ackerman found an especially rich source for her research in the books of the prophets. By condemning particular actions as heretical, the prophets illuminated the very ritual practices and religious beliefs that are "spun" almost into oblivion in other parts of the Bible.

T he title of Ackerman's dissertation,which became her first book, is Under Every Green Tree (Scholars Press, 1992), a reference to Isaiah 57:5, which reads, in part, "you that burn with lust among the oaks, under every green tree." This is a semi-veiled reference to ritual sexual practices designed to "emulate and stimulate" the gods who bring fertility to the land, livestock and humans, says Ackerman.

"The fact that there were Israelites who seemed to find ritual sex religiously appropriate has always pleased me," says Ackerman. "This is not your mothers Bible. It's a lot messier than we're normally told."

Other aspects of worship the ancient Israelites shared with their Canaanite neighbors include ancestor worship, dream incubation, solar worship and child sacrifice. In fact, the prophet Isaiah includes child sacrifice in his condemnation: Verse 57:5 continues, "...you that slaughter your children in the valleys, under the clefts of the rocks."

Putting such a horrific practice into context, Ackerman notes that child sacrifice was extremely common in the ancient Near East at that time. As to why, she says, "No one gets up in the morning and says, 'I am going to do something really sinful today.' These religious practices were obviously very meaningful to the people doing them. Child sacrifice is a vivid illustration of the issue. It must have felt tremendously religious, an act of ultimate devotion to give up their most precious possession."

U nderEvery Green Tree created a buzz in the academic world even before its publication, and the attention came at a good time for Ackerman. She had what she wryly calls "terrible interviewing skills." Her credentials from Harvard had gotten her an impressive number of interviews, but her ill-at-ease manner when interacting with interviewers landed her a job in the bottom tier of the South Carolina state university system. She was the only religion professor at the school, teaching the Bible, Buddhism and everything in between—and she was desperate to leave.

"The book brought my scholarship to peoples attention when I really needed people to be impressed," she says. One of those people was William G. Dever, a noted archeologist of ancient Israel who hired Ackerman at the University of Arizona. Although she disliked Arizona's climate and scenery, it was a wonderful job and she was teaching doctoral students. When the call came from Dartmouth in 1990 about a job opening, Ackerman had mixed feelings, not only about leaving her position in Arizona but about returning to Hanover.

In spite of her reservations, Ackerman interviewed and had what she calls "a miraculous day." Not only did she feel relaxed during her interviews, she was pleased to find that the professors she had admired as an undergrad wanted her to return as a colleague and equal. "It has been a very happy decision," she says of her return.

With her own student experience in mind, Ackerman tackled Dartmouth's social system from a faculty perspective. At various points she invested a great deal of time trying to change aspects of the social life on campus, and she lent her voice to the faculty move to abolish the Greek system. The frat system remains one of her least favorite parts of campus life.

"I wouldn't say that I've made my peace with the decision to keep the fraternities," she says. "I think we'd be a better campus without it, and nothing I've heard in the debates has changed my mind."

One thing she valued as an undergraduate at Dartmouth was very positive relationships with professors, and Ackerman has made a conscious effort to continue the cycle of faculty involvement with students. "Mary Kelley, who's now at the University of Michigan, had drinks with my family at my graduation," says Ackerman. "That really meant a lot to me. Last year at graduation I had dinner with two of my honors students and their families." Ackerman also hosts students at her 1792 farmhouse in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and enjoys the opportunity to be with a small group of students during the religion departments foreign study program to Edinburgh, Scotland, where she travels periodically.

Ackerman now teaches Religion 1, the course that started her journey as a biblical scholar. She also teaches a popular—and controversial—class on biblical archeology. Most of the students in her class assume they will study how archeology coordinates with the Bible. This was the scholarly presumption when the field of biblical archeology was launched 100 years ago. What began as a scholarly attempt to prove the Bibles historical accuracy shifted when the archeological record disproved more than it proved.

"People were looking for the walls of Jericho," says Ackerman. "There was an intellectual crisis when they realized the walls didn't actually tumbledown. In fact Jericho was unoccupied when the walls should have fallen. Many of my students go through a comparable intellectual crisis. They are looking for scholarly confirmation of what they learned in Hebrew school or Sunday school, and they are distressed and irritated to find that the Bible is not the neat, clean package that they'd like it to be or that tradition has suggested it is."

There is a cost to Ackerman in being true to scholarship in the face of faith's disbelief. "It is hard," she says, "to teach students who are angry at what they are learning, and it is sad for me to absorb the brunt of that frustration. Since Dartmouth is experiencing the U.S. demographic trend toward greater fundamentalism, I'm seeing it more rather than less."

N or does Ackerman have simplistic or easy answers for those on the other side of the American cultural divide. Like many feminist scholars in religious studies, she started her career with hopes of reclaiming or unearthing stronger images of women in the Biblical tradition. Her second book, Warrior Dancer Seductress Queen (Anchor Bible Reference Library, 1998), is a close reading of the Book of Judges and looks at women who took advantage of the limited power available to them, including queen mothers, war heroines and religious leaders. But Ackerman says she would write it differently now.

"I'm less optimistic," she says ruefully. "Even within the process of recovering women's history, the limitations are so enormous. And almost everyone who does feminist biblical scholarship has the same arc, becoming more and more discouraged."

In the same vein, gay rights activists have wanted Ackerman to use her extensive knowledge of the Bible and ancient Israel to unearth biblical support for homosexual relationships. Her book When Heroes Love (Columbia University Press, 2005) addresses this question, looking closely at the love between David, the future king of Israel, and Jonathan, the crown prince. Davids lament for Jonathan after his death in battle (2 Samuel 1:26) has been held up as a counterpoint to other anti-gay biblical sentiments, and it is a suggestive text:

I grieve over you, my brother Jonathan,

You were such a delight to me.

Your love to me was wonderful,

Greater than the love of women.

W hile Ackerman supports gay rights, she sees no evidence that th ancient Israelites condoned homosexual relations or even acknowledged the idea of homosexuality—much less specific sexual acts between men. She interprets the data to show a rigid hierarchy of gender roles that made it horrifically sinful to make a man symbolically female by penetrating him. In turn, this analysis contributes to her discouragement about the roles of women in ancient Israel.

"The Bible is unremittingly patriarchal," she says. "In the biblical world it was better to be a male slave than a woman." But Ackerman also says the Bible provides a model for disagreement within its patriarchal model, and she returns to its complexity and difficulty as a source of ongoing fascination.

"The Bible doesn't take its theology as a given, but as constantly open to discussion and debate. The Bible wants us to debate, to argue, to wrestle," Ackerman says. "The best biblical example of this is the Book of Job. He questions God, challenges God. Ultimately God puts him in his place but never says that we're not welcome to ask the questions."

Faithful Scholar "Dartmouth was not the easiest place for me to be socially as a student," says Ackerman. "I spent a lot of time in the library, and many of my closest social bonds were with my professors."

ACKERMAN COMPARES THE BIBLICAL EDITING PROCESS TO THE MODERN POLITICAL PRACTICE OF "SPINNING" PUBLIC OPINION.

"MANY OF MY STUDENTS ARE DISTRESSED AND IRRITATED TO FIND THAT THE BIBLE IS NOT THE NEAT, CLEAN PACKAGE THAT THEY'D LIKE IT TO BE."

CATHERINE FAUROT writes about religion and other topics from herhome in Western NewYork. Her last pieceforDAM was theMay/June 2005cover story, "Finding God on Campus."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

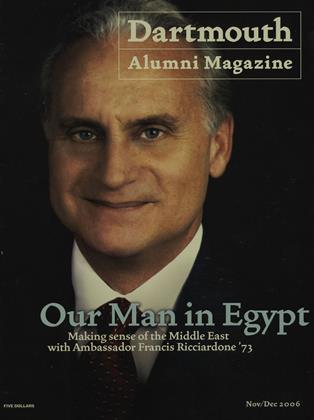

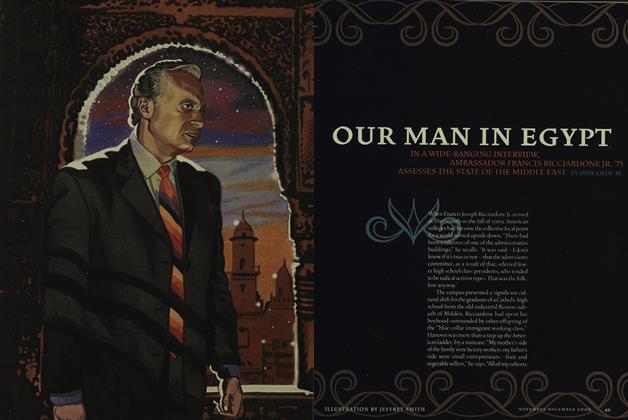

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

November | December 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

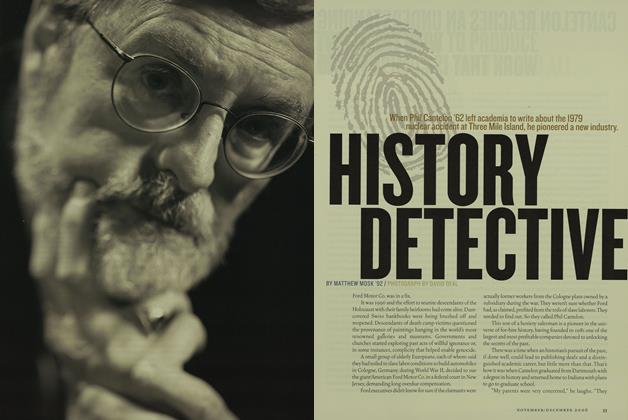

FeatureHistory Detective

November | December 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

November | December 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

November | December 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Sports

SportsTips of the Trade

November | December 2006 By Courtney Banghart ’00 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

November | December 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

Features

-

Feature

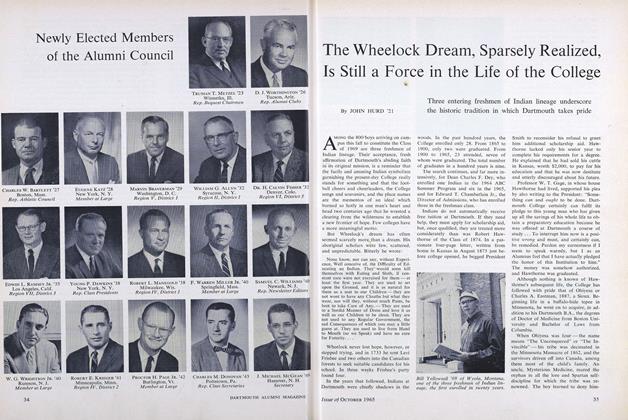

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

OCTOBER 1965 -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Cover Story

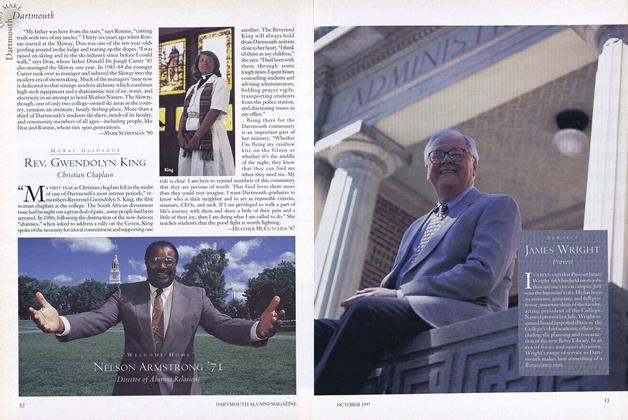

Cover StoryNelson Armstrong '71

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

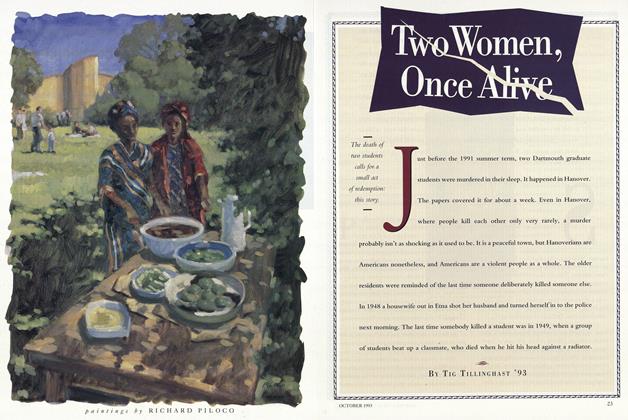

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93