Return of Pinto

He’s back. The alum behind Animal House strikes again with his “awesomely depraved saga of the fraternity that inspired the movie.”

Nov/Dec 2006 Christopher Kelly ’96He’s back. The alum behind Animal House strikes again with his “awesomely depraved saga of the fraternity that inspired the movie.”

Nov/Dec 2006 Christopher Kelly ’96He's back. The alum behind Animal House strikes again with his "awesomely depraved saga of the fraternity that inspired the movie."

FOR NEARLY TWO DECADES CHRIS Miller '63 wanted nothing more than to taste the glory he once knew. He had made a tremendous splash in the late 1970s, when his Dartmouth fraternity experiences at Alpha Delta became the basis for National Lampoon's Animal House, one of the most beloved film comedies of the era.

The 1980s and 1990s, however, were considerably less kind to the writer: He sold a couple of screenplays to the studios, but they languished in development and never got made. Another of his scripts, about a male chauvinistwho wakes up and discovers that God has transformed him

into a woman, was about to go into production—until, that is, Blake Edwards' very similarly plotted Switch came along and turned Millers project into an afterthought. Even his experience with his one produced screenplay, Multiplicity, turned very sour: The original script (which was co-written by Millers wife, Mary Hale) was extensively reworked by two other writers. The finished product, which starred Michael Keaton and Andie MacDowell, opened to indifferent reviews on the same day the 1996 Summer Olympics kicked off—and it very quickly disappeared between the cracks.

"After Animal House I was racing around Hollywood, trying to get things going," says Miller, who still lives in Los Angeles. (Hale died in 2002.) "It worked for awhile, and there was a stretch of time where it didn't work, and that was a drag, because there was a baby coming. The movie industry is a game of Chutes and Ladders, with almost all chutes."

Well, Miller is about to enjoy a long overdue second act: In November Little, Brown and Co. publishes The Real AnimalHouse: The Awesomely Depraved Saga of theFraternity That Inspired the Movie, a raunchy, fast-paced and surprisingly poignant memoir that recounts the writer's sophomore year at Dartmouth, when he first pledged A.D. The book, which Miller says is almost entirely factual (save for a few composite characters, changed names and creatively altered details), draws on the stories he first wrote for National Lampoon magazine in the 1970s, including "The Night of the Seven Fires," about A.D. Hell Night, and "Pinto's First Lay," about his illfated journey to a brothel. But the author has added new material and broadened the cast of characters, and he's offered up a neatly old-fashioned narrative act: The sentimental education of "Pinto," Miller's alter ego, who over the course of the book goes from an overeager, naive virgin to cool, collected (and sexually experienced) man-about-campus.

The result, not unlike the screenplay for Animal House, is an unfettered celebration of shockingly boorish, proudly sociopathic behavior: The night, for instance, one of the brothers scooped human brains off the windshield of a fatal car wreck and served them up with cold beer in the frat basement; or the hazing incident involving a frozen hot dog and mayonnaise that, if repeated these days, would likely result in a few dozen lawsuits being filed against the College.

But the book also probes much deeper than the film. Miller offers up an affectionately detailed portrait of a very distinct era in Dartmouth history, when 1950s propriety was slowly giving way to 1960s liberation. He also portrays Alpha Delta as a place where, hiding beyond all the tapped kegs and projectile booting, there was real heartbreak and pathos. The A.D. we read about turns out to be a kind of haven for decidedly broken souls—a place where men who could barely function in proper society gathered to be with their own. During the course of just nine months nearly a half-dozen of Millers brothers are expelled from Dartmouth; in one quietly devastating moment, an A.D. members homosexuality is exposed—and he promptly disappears from the fraternity, never to be seen again.

Miller believes that the College was undergoing an evolution—one that likely began in the years following World War II but which didn't fully take root until the early 1950s. "[Dartmouth was matriculating] vets from the Korean War, who were there on the G.I. Bill," he explains. 'And these were unlike the boys who were just coming out of prep school. These were guys coming back from a war where they had killed people and eaten dogs. And when they came back they didn't transform back into nice little prep school boys. They caused some serious hell."

According to Miller, this golden period of resplendently rowdy behavior didn't actually last very long—a little more than a decade, perhaps. Miller, who stayed around an extra year to get a degree at Tuck, says by then attitudes about fraternities were already beginning to changenot just at Dartmouth, but at colleges across the country.

"The Vietnam War was going on," he says. "And being in a fraternity wasn't hip anymore. Being in a fraternity meant that you were aligning yourself with the jerks who were running the country."

Miller spent the years immediately after Dartmouth working as a copywriter for an advertising agency in New York City (his most memorable contributions were to General Mills' "I'm cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs" campaign). He began contributing to National Lampoon in 1971. A few years after that the Lampoon editors struck a deal with Universal Studios to produce movies—and they immediately looked to Miller, whose fraternity tales seemed perfeet for the big-screen treatment. Working with Lampoon co-founder Doug Kenney and Harold Ramis, Miller developed a screenplay about warring fraternities at a small Northeast college in the early 19605. ("It was written on clouds of marijuana," he remembers fondly.) When the movie opened in July 1978 it tapped straight into the Zeitgeist: Fouryears after Americas withdrawal from Vietnam the public was suddenly eager to indulge in a bit of Kennedy-era nostalgia. Moviegoers seemed especially enticed by a movie that viewed young American men not as war-battered and soul-deadened but filled with ardor, promise and sexual energy. Animal House earned stellar reviews (Roger Ebert gave it four stars) and quickly turned into a box office sensation, grossing $120 million during its initial run and $20 million more when it was reissued a year later.

What tends to be forgotten, of course, is that, much more than a celebration of the hard-partying lifestyle, Animal House is actually a paean to nonconformity—an exultant middle finger flipped in the direction of the prigs and conservatives who populate Delta Houses archrival fraternity, Omega House. Miller acknowledges that the film was likely directly responsible for the uptick in fraternity membership nationwide throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He also concedes the point that, these days, the movie is often embraced most fiercely by the very conservative, conformist frat boys it's actually making fun of.

"No fraternity brother thinks he's an Omega," he says. "They all think they're like the Animal House brothers. But of course they're not."

That said, Miller has little patience for anyone who would dare to suggest that his movie had any kind of negative impact. Or that it unfairly tagged Dartmouth with a reputation as the least intellectually serious, most party-minded of the Ivies—a reputation that, nearly three decades later, a lot of administrators, professors and alumni are still trying to erase. "What it did was continue a reputation that was already there, and that had always been there," he insists. He says he was last on campus in the spring of2005,whileonatourofNewEngland colleges with his then college-bound son Jack (who ended up at Oberlin). The visit, not surprisingly, included a detour to the Alpha Delta basement.

"The brothers seemed different from when I was there, in the sense that every generation is very different," he says. "On the other hand, there did seem to be a basic love of beer."

As for his new career as an author, after nearly a quarter-century of Sisyphean struggle in Hollywood, Miller sounds positively giddy—particularly when he recounts the details of conceiving and pitching The Real Animal House. It was sold to Little, Brown in the summer of 2004 as part of a two-book deal (a collection of Millers short stories, including a number of non-Animal House pieces he wrote for National Lampoon, will follow, likely within the next 18 months). Working on the manuscript, he says, proved to be a glorious trip down memory lane: He got in touch with many old Adelphian brothers, including ones he had never before met, and their stories enhanced Millers own and helped him to create a more kaleidoscopic portrait of fraternity life at Dartmouth in the early 1960s. Millerwas so jazzed by the experience that he says he's eager to get started on yet another book: A second memoir, about his experiences in New York in the 1970s, running in the same drugs-and-booze-fueled circles as John Belushi and P.J. O'Rourke.

If you were pitching a screenplay of Miller's life,you'd call it a classic comeback story. About the underdog who couldn't be counted down for the fight. About the writer who never lost sight of his passion to tell stories.

You might just say it's like Rocky II meets Barton Fink.

Miller himself puts it much more plainly. "Foryears I did nothing much that I was pleased with or proud of," he says. "But this is my return to the majors."

Miller Time Chris Miller (left) hangs outat an unidentified fraternity house during senior year. "I certainly haven'tbecome stuffy about the things we did,"he says. "I still glory in the crazy stuff."

CHRISTOPHER KELLY is the film critic forthe Fort Worth Star-Telegram in Texas.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

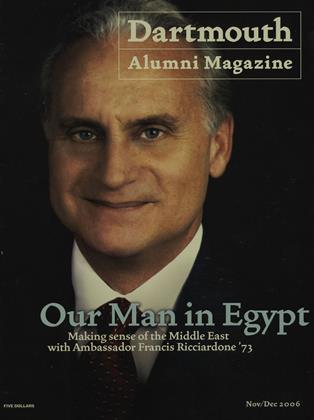

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

November | December 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureNot Your Mother’s Bible

November | December 2006 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05 -

Feature

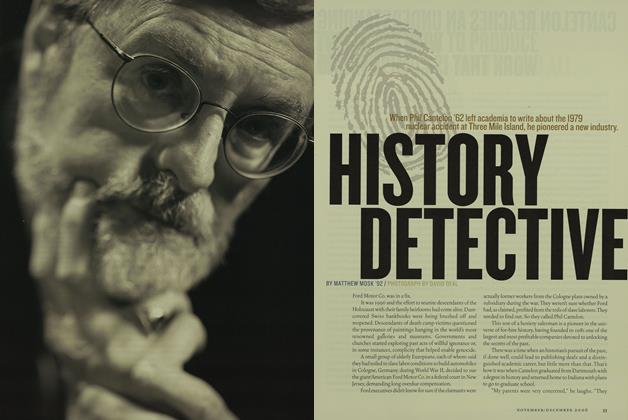

FeatureHistory Detective

November | December 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

November | December 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

Sports

SportsTips of the Trade

November | December 2006 By Courtney Banghart ’00 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

November | December 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

Christopher Kelly ’96

-

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLThe Film Society Turns 50

JANUARY 2000 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Interview

InterviewPicture Perfect

MARCH 2000 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryA Critical Relationship

Mar/Apr 2001 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Feature

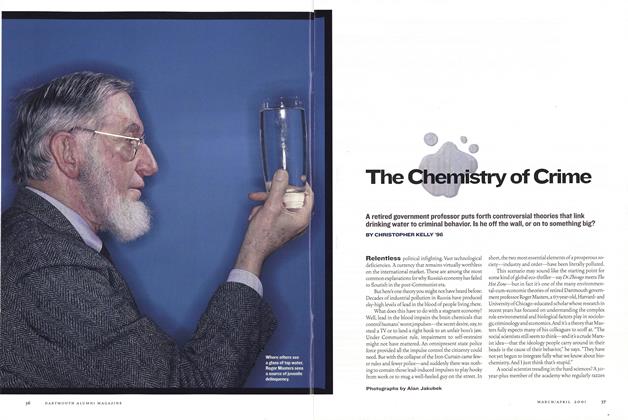

FeatureThe Chemistry of Crime

Mar/Apr 2001 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Feature

FeatureBrenda and Mindy and Matt and Ben

Jan/Feb 2004 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May/June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96

OFF CAMPUS

-

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Off Campus

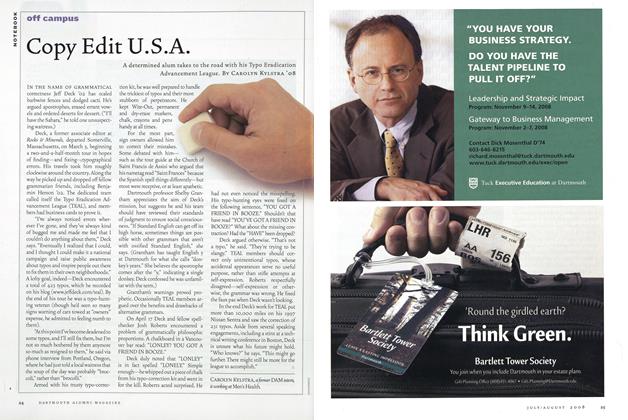

Off CampusCopy Edit U.S.A.

July/August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSWeathering the Storm

Sept/Oct 2008 By Diederik Vandewalle -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSTrading Places

Jan/Feb 2013 By Judith Hertog -

OFF CAMPUS

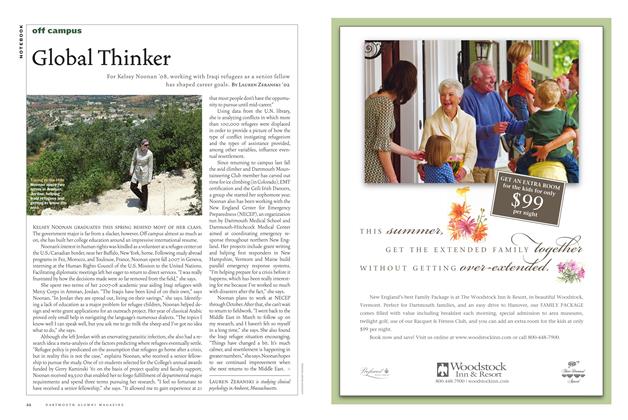

OFF CAMPUSGlobal Thinker

July/Aug 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02