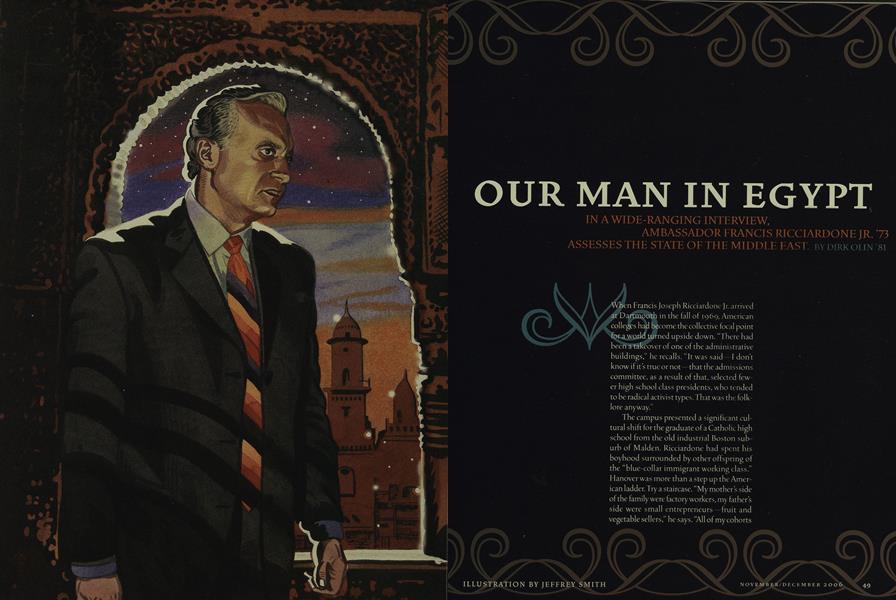

Our Man in Egypt

In a wide-ranging interview, Ambassador Francis Ricciardone Jr. ’73 assesses the state of the Middle East.

Nov/Dec 2006 DIRK OLIN ’81In a wide-ranging interview, Ambassador Francis Ricciardone Jr. ’73 assesses the state of the Middle East.

Nov/Dec 2006 DIRK OLIN ’81IN A WIDE-RANGING INTERVIEW, AMBASSADOR FRANCIS RICCLARDO«E JR. '73 ASSESSES THE STATE OF THE MIDDLE EAST

When Francis Joseph Ricciardone Jr. arrived at Dartmouth in the fall of 1969, American colleges had become the collective focal point for a world turned ups ide down." There had been a takeover of one of the administrative buildings," he recalls. "It was said-I don't know if its true or not-that the admissions committee, as a result of that, selected fewer high school class presidents, who tended to be radical activist types. That was the folklore anyway."

The campus presented a significant cultural shift for the graduate of a Catholic high school from the old industrial Boston suburb of Maiden. Ricciardone had spent his boyhood surrounded by other offspring of the "blue-collar immigrant working class." Hanover was more than a step up the American ladder.Try a staircase." My mother s side of the family were factory workers, my father's side were small entrepreneurs fruit and vegetable sellers," he says. "All of my cohorts who went on to college were the first generation of their families to do that."

He is surely the only one who went on to double-major in French and psychology, graduate summa cum laude and land a Fulbright scholarship in Italy. He then married his high school sweetheart before expatriating to teach and become a self-described "hippie backpacker" around Europe and the Middle East. He continues that journey now as the U.S. ambassador to Egypt.

Since the summer of 2005 Ricciardone has run the diplomatic mission in Cairo—one of Americas biggest permanent overseas embassies—surrounded by another world turned upside down. But if there was ever an ambassador who was more than the cliched campaign donor rewarded by sinecure, it's Ricciardone. (For the record, he calls himself "a lifelong Yankee independent.") Fluent in Arabic and Turkish (as well as French and Italian, of course), he brings years of on-the-ground experience in the Middle East. After a series of U.S. Foreign Service stints—in the Ankara embassy overseeing peacekeeping operations in the Sinai Desert and coordinating Iraqi refugee intelligence from an Amman, Jordan, posting after Desert Storm—he became known as former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright s "czar for overthrowing Saddam."

His service under President Bill Clinton prompted a brief pas de deux with the incoming Bush administrations neoconservatives in 2000. But he danced well, eventually landing an ambassadorship to the Philippines (a post once held by Stephen Bosworth '61, who is now dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy) from 1984 to 1987. Then last year came Ricciardones appointment to his current post.

Dartmouth language professor John Rassias was among those not in the least surprised by the rise of his former protege. After Ricciardone spent the night at the Rassias home in Norwich, Vermont, on the eve of his Egyptian ambassadorial confirmation hearings, the professor waxed rhapsodic to the Manchester, New Hampshire, UnionLeader, calling Ricciardone "fantastic in every sense of the word."

I met Ricciardone in late 2005, during his first trip back to the States since his posting in Cairo. In March and then in August, he again shared his thoughts—specifically about the role he plays in the fast-changing socio-political landscape of the Middle East and more broadly about the continuing strife in Iraq, the ongoing struggle for reform in Egypt, and Israel's retaliation against Hezbollah in Lebanon.

How do you feel about the aftermath of the Israel-Hezbollah conflict of this past summer?

With faith and courage, insight and skill, out of the aftermath of wars we can shape peace. Luck helps, too. In diplomacy, the long view enables us both to deal with deeper threats and to see immediate opportunities. October 1973 saw a terrible war, or perhaps it was the culmination of an episodic single war begun in 1948. The outcome was painful all around, but both sides declared victory, and still do. Nearly six years later, after the intensive engagement of three American administrations—two Republican, one Democratic—in March 1979 Israel and the largest Arab country, Egypt, signed a historic peace treaty. Through three Gulf Wars and numerous Lebanon crises and the chronic Israel-Palestinian conflict, the Egyptian-Israeli Treaty of Peace stands solid today.

Bush administration officials have acknowledged a possibility thatsome already believe a reality: Iraq suffering civil war. In early2006 you counted yourself "soberly optimistic." Are you still?

Remember what I said about the long view. The deadly stagnation of Saddam Husseins dictatorship is over, and this makes everything possible, over time—from democracy to civil war and everything in between. Ultimately, the Iraqis will choose their fate, and we are committed to supporting those Iraqis who choose democracy and freedom.

What is your role on a day like the one last April when there wasa terrorist attack in the Sinai?

One of the primary roles of American embassies anywhere is to take care of American citizens, both routinely and especially in mass casualty incidents like natural disasters, transportation accidents and terrorist attacks. We plan and practice our preparations for such situations so that when the first news breaks of any such catastrophe we can spring an organized, multi-disciplinary team into action. We work with host nation contacts across the government and private sector and we marshal U.S. government resources both locally and globally. Timely, accurate, relevant information is vital, as is the ability to manage it and communicate it at multiple levels. In the April terrorist attack we did all of this, working from an operations center within the embassy. We worked with Egyptian officials and private medical, security and other emergency services to get critical care to the several gravely wounded Americans and to communicate with their families. During and since that attack we also have been in close and productive cooperation with the Egyptians in forensic and intelligence follow-up. This has resulted in the killing and capturing of several suspected terrorists in the April case and apparent disruption of their group.

What's been the fallout from last year's elections in Cairo?

Egypt is a pillar of the Islamic world that has been open to the West for centuries. Egypt does everything in its own, peculiar way, both borrowing from the West and shunning Western influence as it chooses. President Hosni Mubarak has repeatedly affirmed his commitment to political and economic reforms. By Western standards these have been limited and inconsistent, sometimes showing real progress and other times reversals. The case [of Mubarak opponent and reform candidate Ayman Nour] certainly appears to us as a reversal—the [Cairo] Supreme Court rejected his appeal in May and he remains in prison reportedly suffering medical problems. New laws in the summer of 2006 on the judiciary and libel—or press freedom—have produced mixed results, whose meaning Egyptians themselves hotly and freely debate.

But what really matters for the course of history in Egypt is what Egyptians think. Thanks to one of the most substantial democratic advances in Egypt—the emergence of a much freer mass media—we now have a sense of that. Most Egyptians evidently considered 2005 a year of historic reforms, yet many found them insufficient. Others found the results of 2005 stressful and worrisome. I would say Egyptians both want change and fear it. They are deeply attached to their timeless stability, yet they reject stagnation. President Mubarak repeatedly has denied the widely held perception that he is planning to install his son as his successor. If he or [his son] Gamal Mubarak have a plan for such a scenario or, for that matter, any plan to force a succession outside of Egypt's constitutional processes, it is not apparent. What does seem clear is that in amending the constitution to oblige himself to run in the first multi-candidate direct elections in 2005, Mubarak deliberately established a right unprecedented in 7,000 years of Egyptian history: that Egyptians will choose their leader. With all the international and domestic criticisms about the conduct of the 2005 presidential and parliamentary elections, some of which Mubarak has acknowledged and pledged to address, that seems to me grounds for hope.

The 2005 parliamentary vote gave the Muslim Brotherhood and other radicals about 20 percent of parliament. What is the significance of this?

It was an exciting year. It was the first time an Egyptian leader appealed to the peopleand he had to ask them to support him in the face of other candidates.

Of course, the election has also been dismissed as "three minutes of freedom," right?

Yes,but this is a culture where there's traditional apathy or inherent support for the ruler. One surprise for the government was how few people showed up to vote. They were also surprised that the second-highest vote-getter was Nour. So Egyptians are quite excited and anxious. And in parliament its not just the Brotherhood, but 77 percent of the parliament is new.

So is the Bush doctrine of democratizingthe Middle East working?

What we're seeing in Iraq is historic and huge. As I said, I'm soberly optimistic. In five years I still think there's a good chance that the country is going to be on a pretty good track. Iraq won't become Sweden in our lifetimes, but it will never again be Saddam's hell.

Was Iraq's election more than an ethniccensus, and will those results prove asdurable as what you think we're seeing inEgypt?

Sure. Iraq is much harder because we have to try to help Iraqis create a civil society where there was none. In Egypt I'm even more optimistic. I don't think I'm being naive. Egypt has historical institutions of state, not just a dictatorship. It has a strong court system and a sense of the rule of law. Yes, there's corruption and there are abuses. But the sense of law in Egypt is so strong that Egyptian judges are in high demand throughout the Gulf. They're brought in by other Middle Eastern countries to teach law and to actually be judges. That's why they were chosen to be the monitors of the recent election, and where there were abuses some judges wouldn't tolerate it and said vote-fixing was going on.

Might Egypt become the model?

It could. Its stock market was, relatively, the best-performing stock market in the world in the past year. There is a reformist group of economic technocrats in the cabinet. The country has laws that govern customs and finances. They have a freely converted currency. Is it enough? Not by American standards. But more importantly, Egyptians don't think it's enough. And now Nour has been imprisoned. Everybody in Egypt and, of course, Iraq believes it's political.The state is claiming document forgery. Although I said that if they sentence this guy they could well create a Nelson Mandela, he hasn't yet become a national hero. But it's safe to guess that if he pursues his political ambitions, he will have reason to claim his prison time as a badge of honor.

But then you have the problems with Abu Ghraib or circumvented wiretap laws. Do Egyptians ask you about these issues?

All the time. They say, "How can you preach human rights when you do Abu Ghraib?" And I say, "Easy Abu Ghraib was a violation of our own standards. It was dreadful, but the president himself has said so. He said it was disgusting, and we have acted against it."

There was little talk of Palestine during the Egyptian campaigning. Was it all about domestic concerns with, maybe, a subtext of insecurity among the Arab bourgeois about their lack of political evolution?

There's a lot to that. Egyptians do care about Palestine and Israel and what they see as historical injustices and the U.S. role in all that. But not even the Muslim Brothers deny that they'll respect all of Egypt's international obligations. It is telling that in these elections Egyptians were focused on other issues. Corruption, jobs, so forth. That's another reason I'm so optimistic.

Not every Foreign Service officer makes it up the ladder you've climbed. What happened between your first posting in Ankara in the late 1970s and the first Gulf War?

I had these little forks in the road. You make a choice, in your 20s, with no greater thought than that. When I came back from Turkey in the early 1980s there was an opening on the Iraq desk. So I took that. That turned out to be seminal. After three years on the Iraq desk I got preparation to go to Egypt. Again, for no good reason. After a few years I was put on a job out in the Sinai called the Multinational Force, a peacekeeping operation. I went around the Sinai in helicopters and four-wheel drive. The Israelis had withdrawn from the Sinai in April 1982.I worked with Egyptians, Israelis, military intelligence officers. You get to know them real well when you drive around for hours in the desert. There were parties. An Israelis son might have a bar mitzvah and the Egyptian officers would come over for that, and an Egyptian officer would be promoted and an Israeli would go to that. So that gave me five years in Egypt, and then the first Iraq war broke out in January of 1991 and they asked me if I wanted to be the guy to reopen the embassy in Baghdad.

What do you mean when you say theywanted you to open the next Baghdad embassy?

In 1991 I was posted to Amman in Jordan. I was supposed to be ready—as soon as we heard there'd been any kind of a takeover in Iraq—to blitz into Baghdad and open an embassy.

Should we have invaded Baghdad duringDesert Storm?

I never thought we should push on into Baghdad. But we had other options. We had encouraged an uprising against Hussein [Shiites in the south, Kurds in the north], and I will never understand why [General Norman] Schwarzkopf allowed the Iraqi military to put down the uprising. Things were chaotic, I understand that, but at that time we were apparently worried about an Iranian-backed popular Islamic uprising because, frankly, we didn't know what we were doing. Some of us who had some sense of Iraq understood that Iraqi Shiites' primary identity was as Arabs, not Persians.

Later, as the Clinton administration woreon, you worked with Iraqi expats?

Come January of 1999 I got a call saying, "You have to come back to Washington. Secretary Albright wants to speak with you about this job." And I described to her my concerns about having the United States work with Ahmad Chalabi. I thought he was a visionary, a patriot. And I still do. He's a brilliant, brilliant man. I thought deposing Saddam was necessary—a positive thing for the United States—but I thought it required more than giving Ahmad $100 million to work with trainees. You had to prepare for the morning after Saddam goes down.

How could you build democratic institutions—such as schools, courts or a freemedia—when Saddam was still in power?

Well, ifyou're good and you're lucky the people may come to see you as an alternative. So the United States held conferences and worked to develop cadres of judges and prosecutors and schools of law enforcement. We used the FBI academy syllabus. We went over how to draft a constitution. We funded educators creating school curricula and translating that into Arabic. So the Clinton administration strategy was clear: We were looking to contain Saddam, keep him off balance and prepare for a different future. Then came our elections of 2000, and the Bush administration comes in.

Which for you meant Colin Powell?

Right. I'd had some contact with him before. It was clear he wanted nothing to do with regime change. And he saw that I was on the outs with the neo-cons. You'd think otherwise. But [former President Reagan staffer] Dick Perle and those people attacked me for having found excuses to do things other than training and equipping an armed force under Ahmad Chalabi. It became clear that I was radioactive.

Which meant?

The outgoing Clinton administration had put my name forward to be ambassador of Oman. And Powell, who owed me nothing, sent it along. Mark of a good man. But, ironically, there were [Arab] forces there that perceived me as hard-line, and the government of Oman declined to agree to my nomination—though their reasons were unstated. My nomination crashed and burned.

So then your stock suddenly went up withthe neo-cons?

Yes. But for the time being they had me doing restructuring work back in Washington. Then September 11 came and they put me in charge of the State Departments crisis group. Next they looked around at ambassadorial vacancies—remember, we were going into Afghanistan at this point—and they made me ambassador to the Philippines. So I had gotten a much better embassy than Oman, and one with its own Islamic issues. I had three good years in the Philippines when Iraq reared its ugly head again. So in January of 2004 Powell borrowed me to work to set up an embassy in Iraq. The Coalition Provisional Authority at that point wasn't working, and we needed an embassy rather than being the occupier. I got yanked from the Philippines and made four trips into Iraq.

How did your wife, Marie, feel about that?

Not very good. So she came back here [to Washington] also and got a job in the [State] Department. Now she is working with Libyan scientists who formerly had been involved in the Libyan nuclear weapons program, helping them get involved in alternative research projects that can exploit their skills for peaceful and productive purposes, like desalinization projects.

And now comes Egypt, which could provemore important than all the rest.

It's a pivotal country at an historic moment.

You're nearing your first anniversary inthis post. What's been the worst day?

July 12,2006. Just as senior U.S. colleagues had arrived in Cairo to advance diplomacy aimed at resolving the June 25 Hamas kidnapping of an Israeli soldier, we got word that Hezbollah had kidnapped the two Israeli soldiers and killed others. Five weeks of horrific carnage and destruction ensued, followed by a tenuous ceasefire. Besides the human toll to Lebanese and Israelis, the damage to American influence and interests in the region has been historic.

Ambassador in Action Ricciardone (from left)sharing coffee with thegovernor of North Sinai;at Ibshadat primaryschool with his wife,Marie, greeting childrenwho received booksthrough a USAID program; speaking at theAmerican University inCairo last year on thefourth anniversary of theSeptember 11 attacks.

"IRAQ WON'T BECOME SWEDEN IN OUR LIFETIMES, BUT IT WILL NEVERAGAIN BE SADDAM'S HELL." —RICCIARDONE

DIRK OLIN, former national editor for The American Lawyer and a former columnist for The New York Times Magazine, is director ofthe Institute for Judicial Studies in New York City,which publishes Judicialßeports.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNot Your Mother’s Bible

November | December 2006 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05 -

Feature

FeatureHistory Detective

November | December 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

November | December 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

OFF CAMPUS

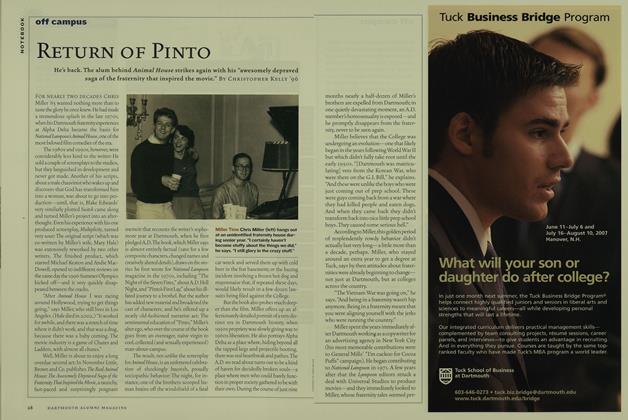

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

November | December 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Sports

SportsTips of the Trade

November | December 2006 By Courtney Banghart ’00 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

November | December 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

DIRK OLIN ’81

-

Cover Story

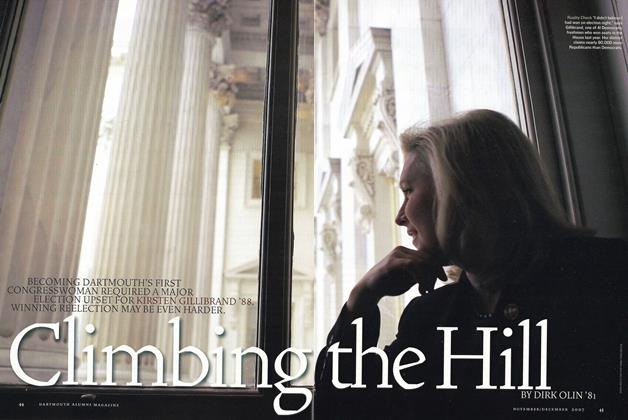

Cover StoryClimbing the Hill

Nov/Dec 2007 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

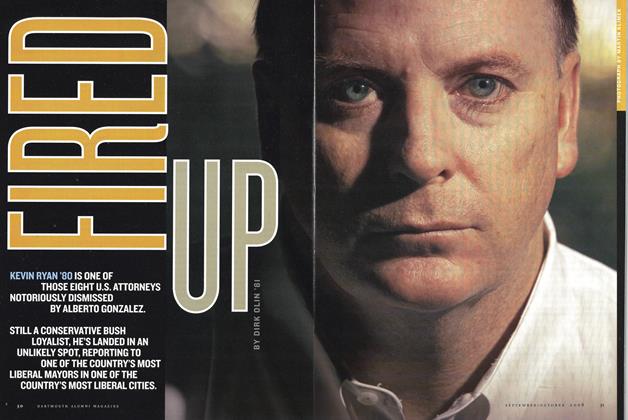

FeatureFired Up

Sept/Oct 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

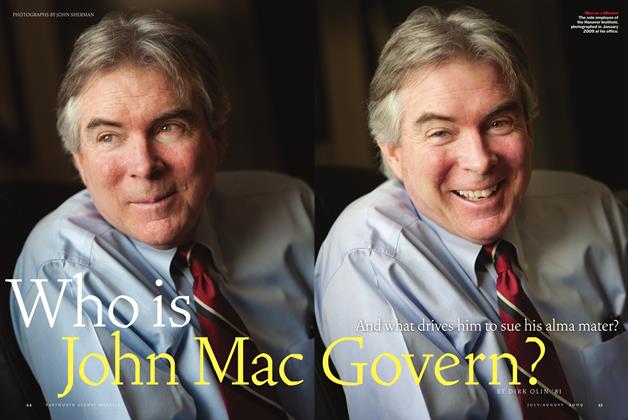

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July/Aug 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Cover Story

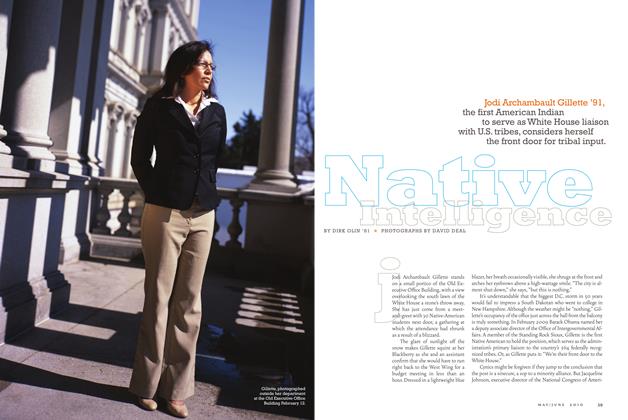

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

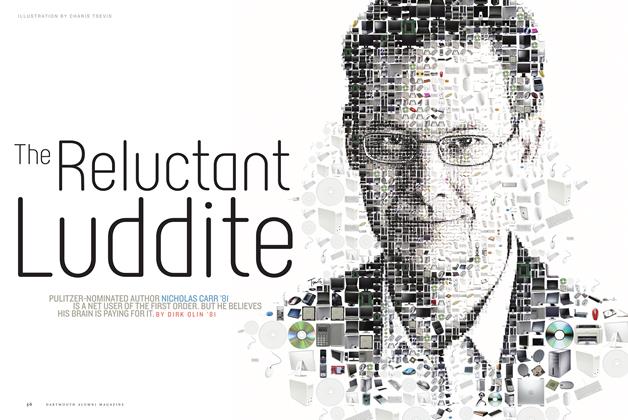

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Article

ArticleSpecial K

MAY | JUNE By Dirk Olin ’81

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMara Rudman '84

March 1993 -

Feature

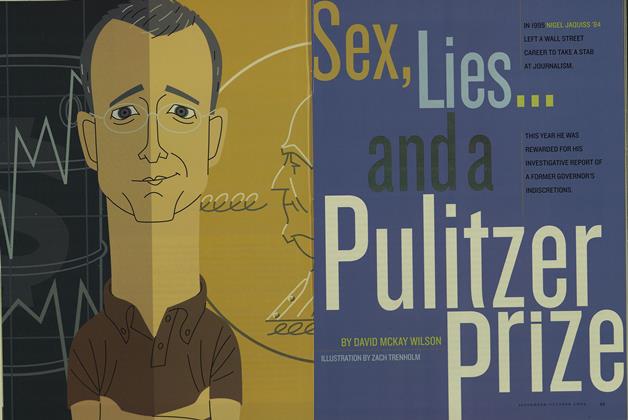

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

Sept/Oct 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

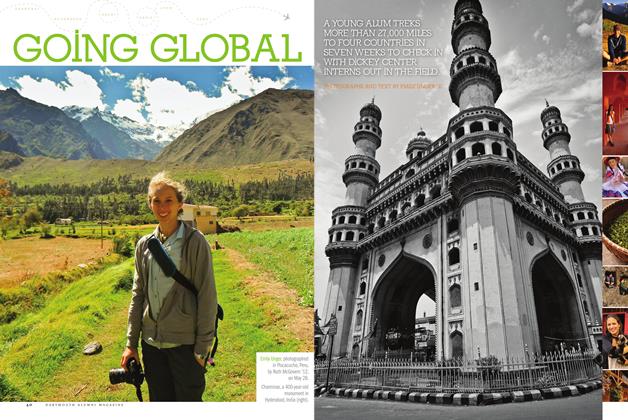

FeatureGoing Global

Nov - Dec By Emily Unger ’11 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

JULY 1959 By JOHN E. BALDWIN '59 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Cover Story

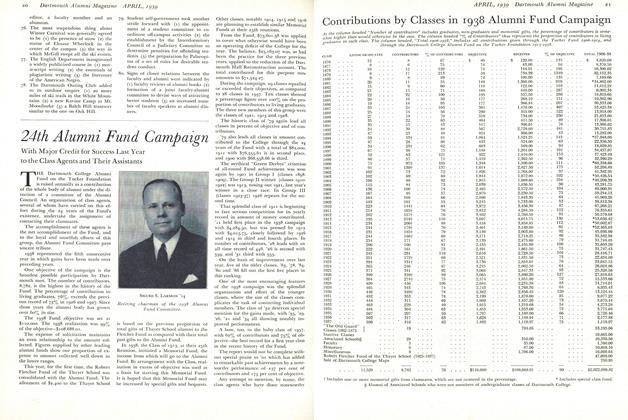

Cover Story24th Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 By Luther S. Oakes '99, Edward K. Robinson '04, Fletcher R. Andrews '16, 2 more ...