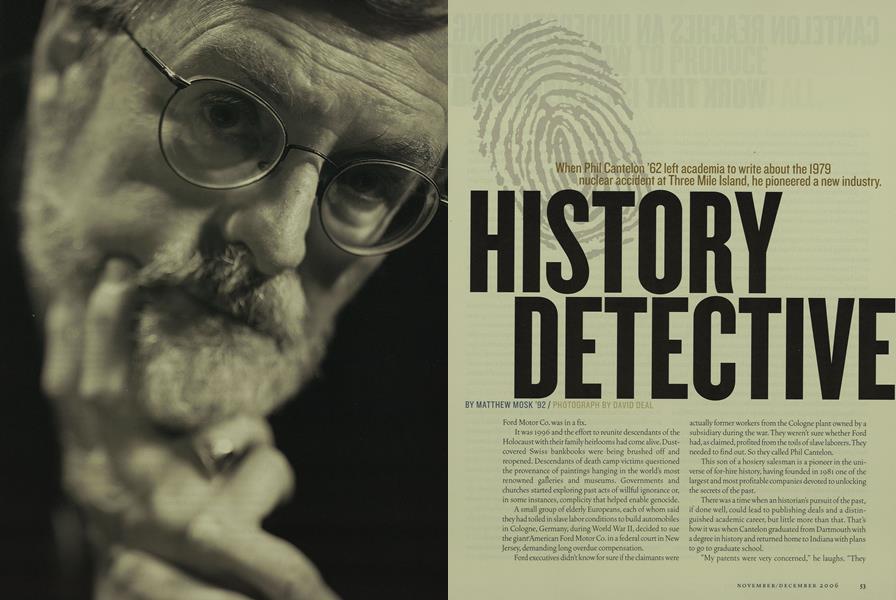

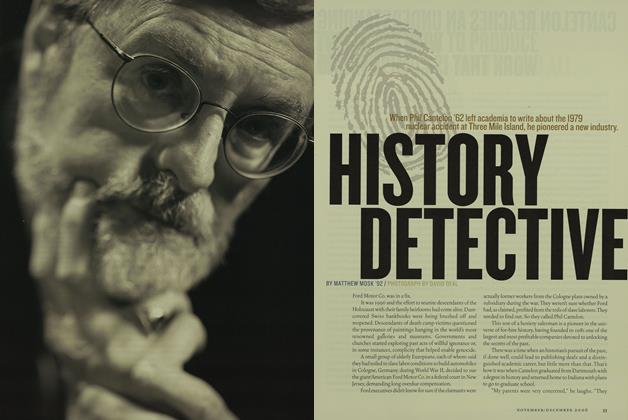

History Detective

When Phil Cantelon ’62 left academia to write about the 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, he pioneered a new industry.

Nov/Dec 2006 Matthew Mosk ’92When Phil Cantelon ’62 left academia to write about the 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, he pioneered a new industry.

Nov/Dec 2006 Matthew Mosk ’92When Phil Cantelon '62 left academia to write about the 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, he pioneered a new industry,

Ford Motor Co. was in a fix.

It was 1996 and the effort to reunite descendants of the Holocaust with their family heirlooms had come alive. Dustcovered Swiss bankbooks were being brushed off and reopened. Descendants of death camp victims questioned the provenance of paintings hanging in the worlds most renowned galleries and museums. Governments and churches started exploring past acts of willful ignorance or, in some instances, complicity that helped enable genocide.

A small group of elderly Europeans, each of whom said they had toiled in slave labor conditions to build automobiles in Cologne, Germany, during World War II, decided to sue the giant American Ford Motor Co. in a federal court in New Jersey, demanding long overdue compensation.

Ford executives didn't know for sure if the claimants were actually former workers from the Cologne plant owned by a subsidiary during the war. They weren't sure whether Ford had, as claimed, profited from the toils of slave laborers. They needed to find out. So they called Phil Cantelon.

This son of a hosiery salesman is a pioneer in the universe of for-hire history, having founded in 1981 one of the largest and most profitable companies devoted to unlocking the secrets of the past.

There was a time when an historians pursuit of the past, if done well, could lead to publishing deals and a distinguished academic career, but little more than that. That's how it was when Cantelon graduated from Dartmouth with a degree in history and returned home to Indiana with plans to go to graduate school.

"My parents were very concerned," he laughs. "They thought I'd never make a dime."

Cantelon's field is called "professional history" or "applied history," and as in many instances where academia and commercialism collide, it has provoked controversy. Some historians have decried the work of professional historians as unreliable, saying no one should embark on a quest for truth and profit at the same time.

Cantelon may have been one of those people had he been granted tenure at Williams College, where he started his academic career, but in the late 1970s academic jobs were constricting. He was forced to seek other options. In March of 1979, as he was considering an offer to teach summer school at Babson, he got a phone call from a friend that would change everything. Robert Williams, a historian working for the U.S. Department of Energy, needed help on a new project.

"He asked me if I'd be interested in writing a history of Three Mile Island," Cantelon recalls. "I said, 'Ahistory? It just happened. What do you mean a history?' " "He said, 'Well, that's what I've been asked to do. People here say this was the most important event in nuclear energy, period. It needs to be documented.' "

And so Cantelon hopped into his car, drove to Washington and signed a contract to write the book. Together, Cantelon and Williams literally scraped documents off the desks at the nuclear plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and interviewed dozens of employees to gather material for a 214-page, minute-by-minute account of an accident that forever altered the field of nuclear energy.

Cantelon says it never dawned on him to call Dartmouth President John G. Kemeny.who chaired the commission tasked by President Carter to dissect the accident at Three Mile Island.

"I probably thought I would only be bothering him," Cantelon says. "I had not seen him since a freshman-year math course, and I was not a particularly outstanding math student."

Before Crisis Contained: The Department of Energy at Three Mile Island was published in 1982 by the U.S. Department of Energy, Cantelon began to realize he was sitting on an even larger opportunity. He and Williams approached the energy department s chief historian, Richard G. Hewlett, who was retiring after 27 years, and the three began meeting in Cantelon's Gaithersburg, Maryland, apartment to talk not about the past but about their future.

They agreed they would each invest the $3,000 needed to form one of the nations first "history-for-hire" companies, History Associates. Hewlett said he would commit his share on the basis that he never have to deal with the federal government again. Cantelon recalled thinking, "Oh God. He's the guy with all the government contacts."

These contacts paid off with a succession of federal contracts, including a job examining the Atomic Energy Commissions records on radioactive fallout from atmospheric weapons testing. Soon government work accounted for 70 percent of their portfolio, and Histoiy Associates' gross earnings climbed from $100,000 in 1981 to $1.5 million in 1986, earning the firm a spot on Inc. magazine's list of fastest-growing small companies.

"Then, in one year, that all went away," Cantelon says.

In 1992 competition from another firm left History Associates without renewal of its most lucrative government contracts, and the company was suddenly at a crossroads. According to a 20-year company history prepared by the firm's own historians, Cantelon made several attempts to branch out into new areas, not all of them successful.

An historic preservation specialist couldn't find clients. And an effort to create an information services division that year found clients initially, but it was fast eclipsed by the seemingly limitless offerings of the Internet.

The company took more work writing company histories and managing large corporate archives. But the sleeper hit was litigation research. The firm began availing its historians to lawyers at a time when a number of suits were being filed against corporations that had operated factories on what had since been designated as Superfund sites. If the corporations could prove that some prior landowner had fouled the acres around their factories, they could attempt to saddle someone else with the heavy financial burden of cleaning it up. Rather than poring through land records themselves, the lawyers began hiring History Associates.

It was in this context that a law firm representing the Ford Motor Co. reached out for help in understanding the troubling past at its facility in Germany. James Lide, the History Associates partner charged with heading up the investigation, says Ford executives first approached Histoiy Associates in April 1998. Ford had already started an internal review to find records of the Cologne operation in its corporate records, but recognized it would also need to do a great deal of probing into other sources, both at the U.S. National Archives and in Germany.

Lide hired German researcher Katrin Paehler to plumb the Cologne factory for clues. "She basically borrowed a pair of workman's overalls and went through every building, basement, attic, closet, using a master key to the entire plant," Lide says. "My favorite story of hers is that she even went so far as to climb up a disused water tower at the plant since we found reports here at the U.S. National Archives that suggested the company may have been storing records there at the end of the war." The tower was empty.

Whether History Associates' findings would help or harm Ford's image was never a concern, Lide says. "Our role was to locate any relevant documentation and providean historical analysis of what the documents indicated," he says. "In other Words, we left it to the attorneys and public relations people to worry about any legal or public relations implications."

Even as historians worry that such research can result in a whitewash of the past rather than a candid inspection, David B. Sicilia, an associate professor of history at the University of Maryland, says commissioned work has become more accepted as it has evolved to include more than just a "celebratory" look at the company or individual who is footing the bill.

"It's a mistake to think that just because someone does research for hire that they'll automatically be corrupt," says Sicilia, whose specialty is business and economic history. "It really depends on the particular project. A lot of historians-for-hire have contracts that safeguard their editorial control over their work.

During work on a book chronicling the history of the Bank of New York, Cantelon realized firsthand the potential for uncomfortable situations when editorial control is in the hands of the client.

As he researched the rich history of the bank founded by Alexander Hamilton—the oldest bank in the country still operating under its original name—Cantelon took an interest in its role in a 1972 scandal involving Robert L. Vesco, the New Jersey fugitive financier who was charged with looting a Swiss mutual fund operator. This blot on the banks history, which led the bank to pay a $20 million settlement, was one that then-bank chairman J. Carter Bacot didn't want to relive in a book he was giving out to his 5,000 dearest depositors.

As Cantelon recalls it, the two met in Bacot's office. "I don't want to go back over that, Bacot told him. "I know the story. We learned some lessons from that. But thats not what the purpose of this book is."

"I argued with him," Cantelon says. "I said, 'It happened, didn't it?'" Cantelon contended that the bank looked pretty good in the episode because bank executives eventually helped expose the swindle.

Bacot replied, "No, it was a very hard time for us." He would not relent.

"Finally," says Cantelon, "I met with our author, who was writing it for us, we talked about it and decided to let it go. The Vesco story was deleted and never addressed in the book.

Cantelon says that because of the nature of the product an internal history being passed out to depositers he wasnt uncomfortable with the decision. But with most of the firms work, he says, he reaches an understanding with the client that he intends to produce work that is complete and accurate, warts and all.

In this respect, Cantelon believes the Ford case represents the best of what professional historians can accomplish.

Work by Lide and his colleagues resulted in the 2001 release by Ford of a report chronicling the labor shortages in Germany that led first to the use of foreign workers and then, beginning on August 13,1944, to the use of inmates from the Buchenwald concentration camp. Researchers found, for instance, that workers toiled in 12-hour shifts without food or pay and were guarded by armed SS soldiers.

Fords insistence that the results be made public was something of a gamble, Cantelon says. No one knew how it would play.

John Rintamaki, Fords chief of staff, issued a statement at the time saying the publication of the study was a critical aspect of the three-year endeavor. "By being open and honest about the past, even when we find the subject reprehensible, we hope to contribute toward a better understanding of this period of history," he said.

The work was the first in a sequence of contracts History Associates signed to research the uglier aspects of a company's past, and Lide says the Ford case set the stage for all of the projects to conclude with a frank disclosure by those companies as to their past actions. After its work with Ford, History Associates uncovered that predecessor banks of financial giant JPMorgan Chase & Co. listed approximately 13,000 slaves among the property covered by mortgages given to the banks between 1831 and 1835. Furthermore, the firm owned about 1,250 individuals as collateral.

Cantelon believes the fact that an open, honest historical accounting did not prove harmful to Ford was particularly instructive for JPMorgan Chase. It set a precedent that making things available, in the end, would not destroy the company. In fact, Cantelon says, clients realized "this is a great thing to do." When History Associates did its research for JPMorgan Chase, he says, all the findings went right up on the Internet. It was a sign, Cantelon believes, that professional historians have attained a degree of credibility that matches their counterparts in academia.

Their objectives, after all, are the same. As Cantelon and Williams wrote in the introduction to Crisis Contained, the goal was "telling the story, distinguishing the significant from the insignificant, comparing planned or intended actions with what actually happened, and making known the unknown."

CANTELON REACHES AN UNDERSTANDING WITH THE CLIENTWORK THAT IS COMPLETE ANO THAT HE INTENDS TO PRODUCEACCURATE,

MATTHEW MOSK/S the Maryland statehouse reporter for the Wash- ington Post and a regular contributor to DAM. He lives near Annapolis,Maryland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

November | December 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureNot Your Mother’s Bible

November | December 2006 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’05 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONFailing the Test

November | December 2006 By John Merrow ’63 -

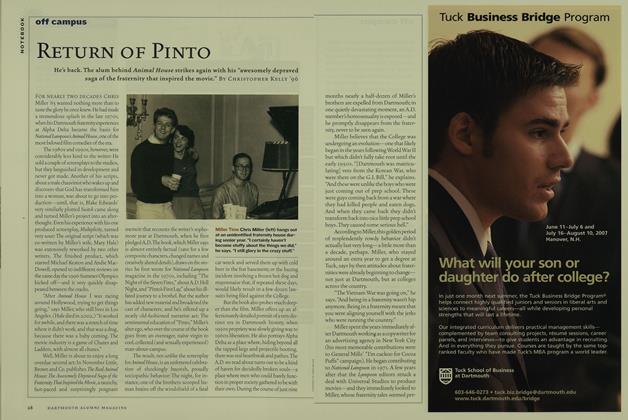

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

November | December 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Sports

SportsTips of the Trade

November | December 2006 By Courtney Banghart ’00 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

November | December 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

Matthew Mosk ’92

-

Feature

FeatureHistory Detective

Nov/Dec 2006 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

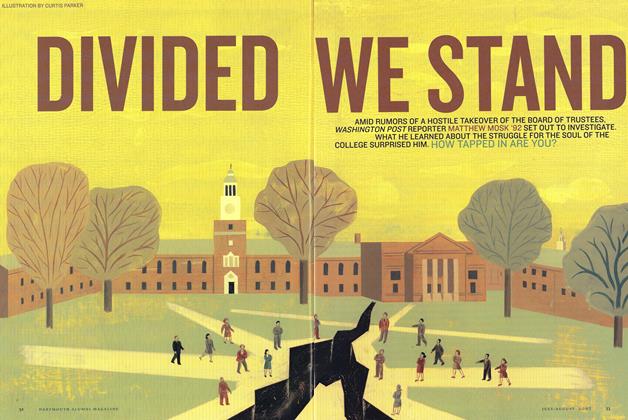

Cover Story

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July/August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

COVER STORY

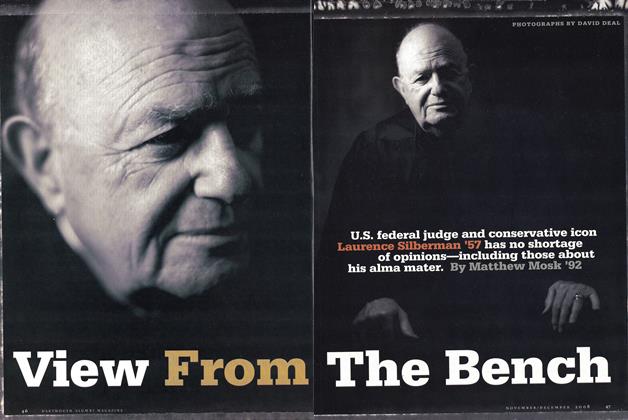

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Dissenting Opinion

Nov/Dec 2010 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

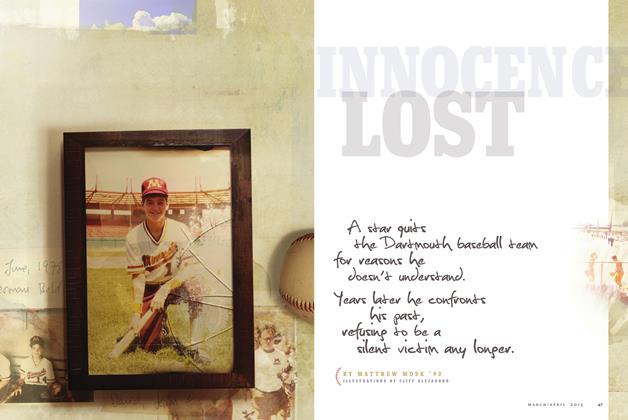

FeatureInnocence Lost

Mar/Apr 2013 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

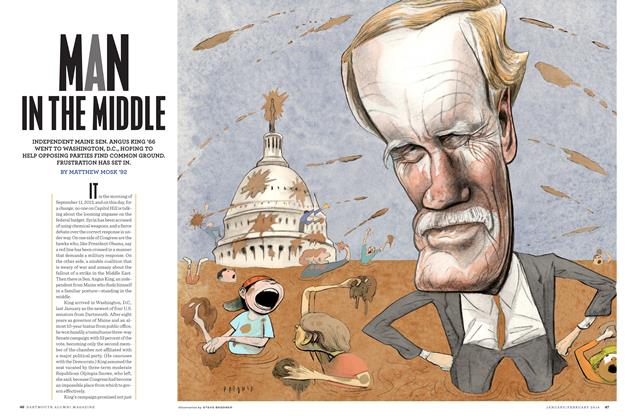

FeatureMan in the Middle

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92

Features

-

Feature

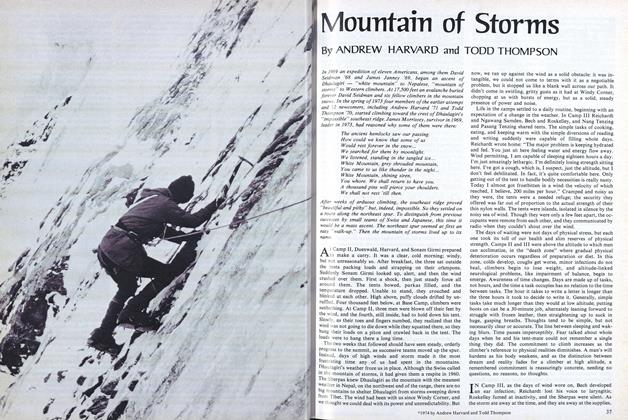

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

JUNE 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/Aug 2013 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

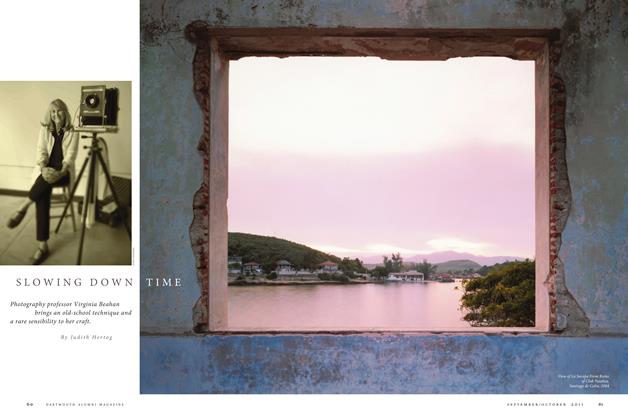

FeatureSlowing Down Time

Sept/Oct 2011 By Judith Hertog -

Feature

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

JUNE 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

FEATURES

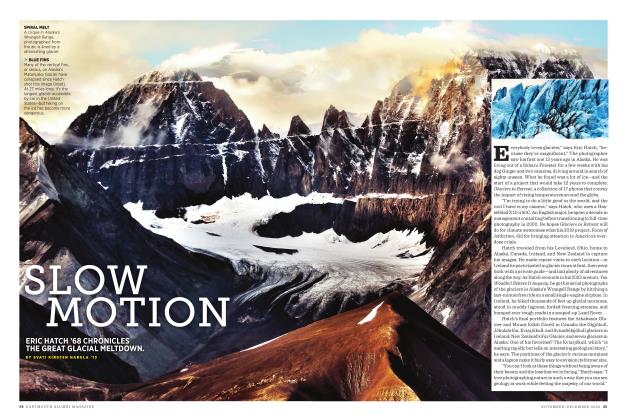

FEATURESSlow Motion

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13