Daily Lessons

Working at The Dartmouth more than 50 years ago taught the value of taking responsibility—and of giving it.

May/June 2006 Ken Roman ’52Working at The Dartmouth more than 50 years ago taught the value of taking responsibility—and of giving it.

May/June 2006 Ken Roman ’52Working at The Dartmouth more than 50 years ago taught the value of taking responsibility—and of giving it.

I'VE ALWAYS ENVIED CLASSMATES who had a relationship with a professor at Dartmouth that changed their lives. I had several inspiring teachers, but no such paragons. I also envied those who had mentors, describee by former President James O. Freedman as teachers who worked with and encouraged their proteges. I didn't have one of those either.

This absence of special relationships prompted me to consider who did influence me at Dartmouth. The answer was easy. It was an institution— the constellation of people and issues that surrounded me for four years on TheDartmouth.

Not The Daily Dartmouth, although it was daily (except Sunday). Just TheDartmouth, "The Oldest College Newspaper in America." Not the oldest daily or the oldest continuously published paper, just the oldest. Daniel Webster, class of 1801, was a contributor, we liked to remind people. It was said we didn't graduate from Dartmouth, we graduated from The Dartmouth. It certainly taught us and guided us. Here are some of the things I learned.

MY FRESHMAN YEAR WAS AN ELEC- tion year—President Harry Truman vs. New York Governor Tom Dewey, with Dewey far ahead. Even Henry Wallace, on the Progressive Party ticket, ran ahead of Truman in a campus poll.

For coverage of breaking news, TheDartmouth was the only game in town. There was no local TV station. The Hanover Gazette was a weekly. The closest daily, The Claremont Eagle, was 35 miles away. We were the local daily—with an Associated Press (AP) wire.

In those primitive days, type was set on a clanking Linotype machine at the Gazette's printing plant just off Main Street. Six days a week an entertaining, foul-mouthed French-Canadian with the memorable name of Al l'Ecuyer (pronounced "le queer") showed up around 6 p.m. to set the next day's edition in type. The night editor followed shortly with the news stories, ready to be set, and stayed until the paper was put to bed (around 1 a.m.). He was the final decision-maker on which stories made it and which were cut.

For photos with national stories,

Ecuyer poured hot lead into cardboard mats the AP mailed in anticipation of events. Since the Republican ticket was a sure winner, we were sent two-column mats of Dewey and vice-presidential candidate Earl Warren, and one-column mats of Truman and running mate Senator Alben Barkley of Kentucky.

As the evening wore on, however, there was no clear winner, and Pete Martin '51, the night editor, found himself staring at gaping holes on the front page. Finally, around 6 a.m., he had to make a call. With nobody around to question his decision, Martin opted to run the pictures of the Republican ticket upside down—with the headline, "Democrats Leading in Upset." We may have been the oldest college paper, but that wasn't going to prevent Martin from being creative and taking responsibility, virtues clearly admired (and expected) by the top editors.

EVERY WEEKDAY AT NOON THE editorial staff assembled at our Robinson Hall offices for the critique of that day's edition by the managing editor, who had marked his comments on the paper with red grease pencil. The marked-up paper remained on display in the staff room, its lessons there for all to study and digest.

The managing editor that year was Frank Gilroy '50, who later became editor- in-chief as well as a Pulitzer Prize- winning playwright (The Subject WasRoses). Gilroy's criticism carried the extra barb of literacy. Headlines that "revealed" information were impaled with a red, "Only God reveals. Man discloses." Our style book, indicating proper usage, started with the words: "Accuracy. Terseness. Accuracy." With insight and wit Gilroy sharpened our thinking and our writing.

WE ALL KNEW THERE WAS A LIBERAL tradition at the paper, going back at least to editor-in-chief Budd Schulberg '38, who went on to literary fame with novels (What Makes Sammy Run) and movies (On the Waterfront). Schulberg showed his sympathies as student editor by supporting striking Vermont quarry workers. Worse, the quarry was owned by an alumnus and major contributor. Schulberg and the paper stood firm, with the support of the administration.

Ted Las kin '51 followed Gilroy as editor- in-chief. It was the McCarthy period. Whittaker Chambers and the Pumpkin Papers. The McCarren Immigration Act. Douglas Mac Arthur challenging Truman, to the cheers of the right wing. Laskin strode into the fight (with mixed support from his editorial board). The largely conservative student body retaliated with letters to the editor. Laskin believed in the Tightness of his cause, and never flinched.

As a matter of principle the paper ran several editorials every day. While the guideline was that we shouldn't be writing about Afghanistan if Baker Library needed new lights, there was a larger principle: the right to comment. More than a right—a mandate. There must be an edtorial everyday, Laskin preached, whether or not we have something to say.

The charter to take a position on issues beyond the College was long-standing. We savored the story of the 1940 editorial board making the case that the war in Europe was our war, too. When challenged to do more than just editorialize, board members debated the point and, conceding its merit, resigned from the College and drove to Boston to enlist.

I TOOK OVER AS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF the spring of 1951, a period of Red-baiting excesses by the McCarthyites. Publisher William Loeb of the right-wing Manchester Union-Leader dispatched a reporter to Hanover to check the new United Nations flag and make sure it was not flying higher than the American flag (part of a series to "find red tinges on the ivy")-The equally conservative New Hampshire State Legislature got into the act with a bill proposing that teachers take a loyalty oath and swear they would not encourage students to overthrow the government.

We knew an attack on academic freedom when we saw it, so I wrote an editorial to expose the flaws of this pernicious legislation, the Hart Bill. Editorials were unsigned, to signify they represented the views of the paper, and I enlisted the support of the entire editorial board. We also agreed I would go to the hearings and read our editorial into the record.

I drove to Concord and found myself in a cartoon-like situation. Opposing the bill with me were the Dartmouth Christian Union, the left-leaning Progressive Party and the Communist Party of New Hampshire. Support for the bill was led by the chairman of the Americanism committee of the American Legion. When the report on the hearing appeared on the front page of the Union-Leader, my father called to ask what was going on. I had to agree it didn't look terrific.

Back in Hanover, President John Sloan Dickey '29 called me in. We talked about the bill and his experience in the State Department working with Alger Hiss. He was convinced Hiss was guilty. While Dickey disagreed with some of our editorials, at no point did he suggest the paper should back down. Instead, he suggested I visit trustee Dudley Orr '29, who indicated privately the bill would be killed. It was. With Dickey there were no demands, only an open door. I've often thought about the sense of responsibility that was invested in us as student editors.

DURING MY YEAR AS EDITOR-IN- chief Schulberg published The Disen-chanted, his fictional account of working with F. Scott Fitzgerald in his declining, alcoholic years on a movie about Winter Carnival. (Winter Carnival used to show up on late-night TV.) Schulberg was my hero. I had read his earlier books and was excited to meet him when he came to Hanover. I regret not saving the dust jacket where he wrote that being editor of The Dartmouth was the most important thing he ever had done. At the time I was gratified by the comment but regarded it as a bit of overstatement. Since then I've begun to see some truth in it.

There must be an editorial every day, the editor preached, whether or not we have something to say.

KEN ROMAN spent a career in advertising,capped by serving as chairman/CEO of Ogilvy& Mather. He is the author of two books, Writing That Works and How to Advertise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

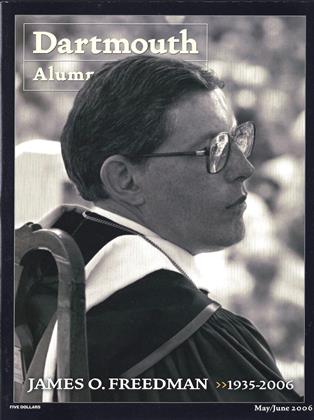

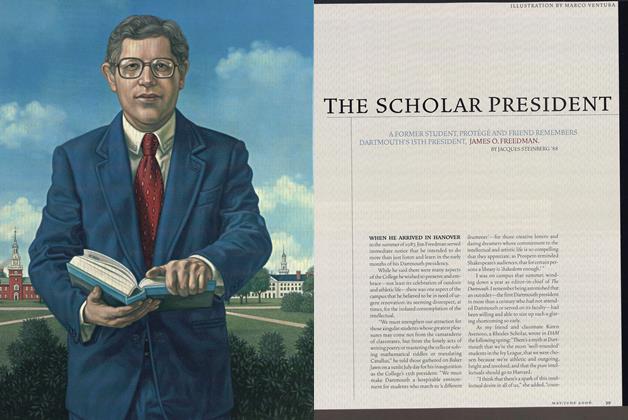

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May | June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

FeatureCapitol Steps

May | June 2006 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

FeatureThe Producer

May | June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May/June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

MAY 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeet the Beatles!

JULY | AUGUST 2019 By RICHARD HERSHENSON ’67 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeasure of the Mind

Mar/Apr 2002 By Robbing Barstow ’41 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBreakaway

MAY | JUNE By SAM HULL ’56