River Dance

Two buddies, a cool current on a summer day, and the unforgettable lightness of being.

Sept/Oct 2002 Jonathan Agronsky ’68Two buddies, a cool current on a summer day, and the unforgettable lightness of being.

Sept/Oct 2002 Jonathan Agronsky ’68Two buddies, a cool current on a summer day, and the unforgettable lightness of being.

RICK FLOORED THE ACCELERATOR with the hand controls, pushing the light blue Fury to its limit. We hurtled down the twisting blacktop past wood-frame houses, cows and weathered barns, rural mailboxes and birches, our hair blowing in the wind, our lips wearing the adrenaline smile of daredevil youth. Only minutes after leaving the Dartmouth campus, six miles away, we were crossing the top of the thousand-foot-long earthen dam near Union Village, Vermont. At the end of the dam, the car left the pavement and kicked up a trail of dust as we raced down the dirt and gravel road flanking the Ompompanoosuc, the river with the onomatopoetic Indian name that feeds the dam. Rick stopped the car near a cluster of pines. There were no other cars around. He pulled out a joint.

"It's a great life in New England," intoned the announcer for the College radio station. "Live it with WDCR."

Who could argue with that, we thought, as we passed the feel-good cigarette back and forth. It was the summer of 1970, an idyllic interlude in politically troubled times for 19-year-old Rick, an Argentine-born Californian and child of divorce who was heading into his senior year at Dartmouth, and his long-haired, bearded partner in crime, who at 24 had just returned to the all-male bastion after flunking out a second time earlier that year. When the DJ spun Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze," we both croaked along in stoned unison: "'Scuse me while I kiss the sky!"

A few minutes later, properly stoked, we started down the woodsy hill leading to the falls, where on hot summer afternoons college students and townies ("pinheads" and "emmetts," respectively, in the local jargon), with uncharacteristic cooperativeness, shed their inhibitions along with their clothes to partake of the cool, clear, chest-deep waters together. I led the way, making sure I didn't get too far ahead of Rick, who was making his way on aluminum crutches—which he called "sticks"—down the steep trail strewn with pine needles slippery enough to drop me on my tail a few times during previous visits. But Rick, who had the upper torso of a gymnast, made the descent look easy, his powerful arms and shoulders swinging his shriveled legs between his crutches almost as an afterthought. We both arrived at the sandy river bank, 40 yards below, without a slip.

The falls on this late summer afternoon were deserted, the usual complement of nymphs and satyrs nowhere in sight. The river, and all it conveyed to us, was ours and ours alone to enjoy. Seating himself on a rock, Rick quickly stripped off his T-shirt, jeans and leg braces, then lowered himself into the river and began stroking smoothly, even gracefully, toward the deep pool directly beneath the falls.

"Come on in Jo-Jo," he called. "Don't be a pussy!"

I jumped in, shrieking joyfully at the shock of the heart-racing, scrotum-tightening iciness of the water. Rick ignored me, a quiet smile on his face, as he sidestroked and backstroked, breaststroked and crawled, released temporarily from the constraints of gravity and the unwanted legacy of a childhood bout with polio, a muscular merman free at last in the aqueous element.

Later, he called from the river to a figure reclining on the bank: "Hey, Wildman, could you hand me my sticks?"

I roused myself, picked up the crutches, waded into the shallows where a seated Rick already had strapped on his leg braces. I helped Rick stand, then held his crutches upright as he slipped first one, then another of his brawny forearms into the braces and gripped the rubber-covered handles. For just a moment, as he stood in the waist-deep water, he seemed caught between two worlds, the one in which he had just enjoyed a brief interlude of freedom and the one with a heavier gravity that never let him forget his handicap. But Rick's face betrayed only the look of a man who had learned to embrace his human limits with more grace and courage than many of his contemporaries who, on the surface at least, seemed healthy enough.

Walking behind him, I watched as Rick planted his sticks into the earth, swung his braced legs forward and, using them as an anchor, propelled himself up the hill. We both were blowing and sweating when we reached the top, as much from the effect of the grass, I suspect, as the exertion.

BACK THEN, DRUGS AND HILL CLIMBS weren't the only things that left one feeling breathless, enervated, even paranoid. The country was being torn apart politically by an undeclared war. A president who'd promised to bring us peace with honor was bringing us lies and more body bags instead. Inner-city blacks, after their greatest leader was slain by a white gunman, seemed to have lost their faith in the efficacy of nonviolent protest. We all faced these problems together; but Rick's extra burden was personal, immediate, apolitical, real enough to touch.

In December 1970, just four months after Rick and I swam together in the Ompompanoosuc, I finally completed my studies and was awarded a B.A. in English. On a frigid winter night I packed my gear, along with my weimaraner, Irving, into my beat-up '63 Impala with its broken heaterdefroster. For the next 12 hours, stopping frequently to chip ice from the frozen windshield, we shivered our way home to the nations capital, where I would take a series of blue-collar jobs before finally launching myself as a writer. Psych major Rick stayed in Hanover for another six months, graduating cum laude from Dartmouth in June 1971, then headed for Madison, Wisconsin, where he would eventually earn a master's degree in city planning.

In August 1971, in an outdoor ceremony near our alma mater, Rick married 19-year-old Ann Pike, a nursing student at Indiana's Ball State University, whom he had courted for just over a year. Following the nuptials the wedding party drove in a caravan to the river: With Edenlike innocence, men and women in their 20s, strangers and friends alike, stripped to their most vulnerable selves and waded into the pristine waters of the Ompompanoosuc, just below the falls.

After returning to the capital city, I wrote a poem memorializing the occasion and sent it to Rick and Ann as a wedding gift. I kept a copy and, every so often, I pull it out and read it again. I guess all of us, from time to time, need to be reminded of the madcap days of our youth when nothing seemed impossible, when two young men in the peak of their lives, could go down to a country river, one on crutches, the other witness to an unforgettable act of self-liberation; both able to postpone, for a magical moment, the hard choices of adulthood looming just around a bend in the river.

Today Rick Paris '71, vice president for humanaffairs at the Children's National MedicalCenter in Washington, D. C., is the father of twoand still happily married to Ann. JonathanAgronsky lives in the capital city and still makeshis living with a pen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

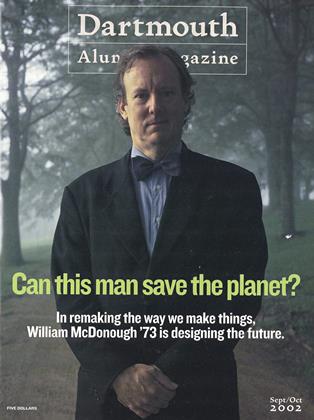

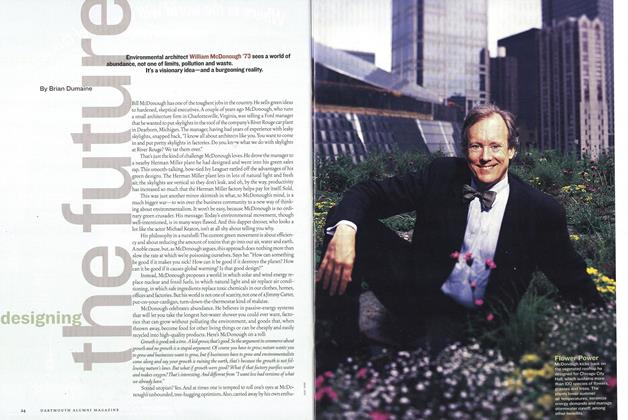

Cover StoryDesigning the Future

September | October 2002 By Brian Dumaine -

Feature

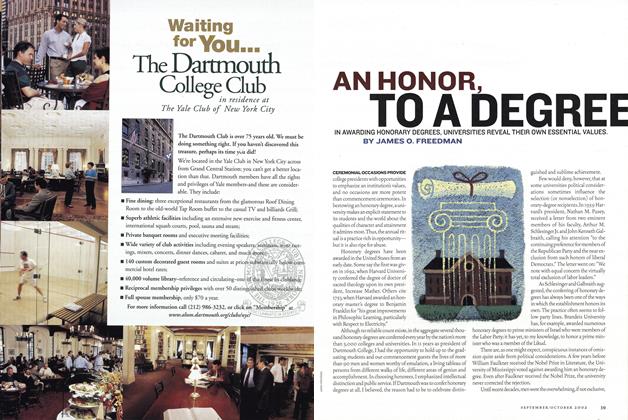

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

September | October 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

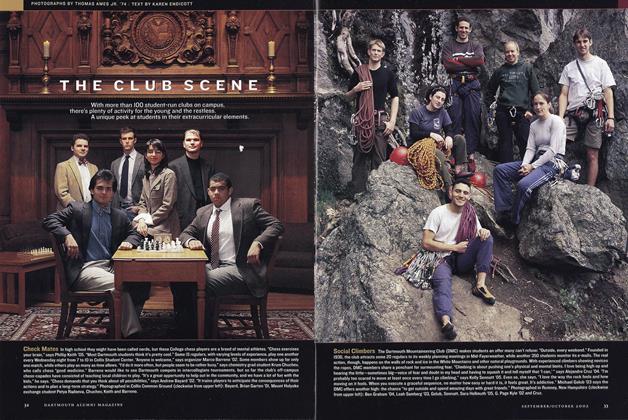

FeatureThe Club Scene

September | October 2002 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2002 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Aesthetics

September | October 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

September | October 2002 By Abby Klingbeil

Jonathan Agronsky ’68

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGetting the Picture

May/June 2008 By Andrew Mulligan ’05 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYClose to Home

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2022 By APOORVA DIXIT '17 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYClutch Situation

July/Aug 2013 By Daisy Alpert Florin ’95 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYValentine for Life

Mar/Apr 2013 By Steve Brosnihan ’83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYReel Oddity

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By TOM ROPELEWSKI