A former student salutes his mentor—classics professor Edward Bradley- who retires in June after 43 years at Dartmouth.

"DAMMIT, MAN, YOU MUST COME to Rome with me! We'll walk in the footsteps of the saints!"

For years those words, spoken to me by professor Edward Bradley in his Reed Hall office, spring quarter 1989, have rung in my ears.

I met Professor Bradley in my first class at the College. Latin 3 met at 8 a.m. on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. I slept through my alarm on the first day of college and—without time to take a shower—put on a baseball cap to cover my unruly bowl cut and ran to class. Breathless, I arrived a few minutes late. Bradley looked at me disapprovingly: "No hats in class." Bad-hair terror consumed me for the next 50 minutes.

Our little Latin class came to be less terrified of "Bradley, the Latin God," over the course of the quarter. He lived on a mountainside past White River Junction, Vermont, and his commute was often our salvation. If the gods were smiling on us, Bradley had listened to a commercial radio station on the drive in and was sure to be completely torqued about the poor grammar in the latest McDonald's commercial. If we played our cards right, we could stoke the fire of his outrage and keep him talking about the devolution of the English language for nearly the entire class period, and that meant no Latin. We took to calling him "Bradley, Master Grammarian" behind his back, of course.

I took off both the spring before and the fall after my sophomore summer, and when I returned in January of my junior year it seemed all of my friends were on foreign study trips (I had failed to get into the history departments trip to Scotland). I ran across Professor Bradley, who invited me to join him and a group of guys for pick-up hockey a couple of times a week at Campion Rink on the outskirts of Hanover. I told him I didn't have a car. He said he'd give me a ride.

Over the winter, as we drove back and forth to the rink, we started to talk about faith. I was a Protestant. He said he was a "born-again Catholic," a phrase I'd never heard. He told me about his spiritual journey. I told him about mine. We talked hockey, campus politics, grammar and women.

When I saw a sign my junior spring announcing a meeting for the classics department's foreign study program in Rome, I swung by Bradley's office to ask about it. He'd be leading the second half of the FSP.

I was ambivalent, I told him. To go on that trip would mean missing senior fall, Dartmouth Night, football games....

Of all the words that pass others' lips and slip into our ears in a lifetime, so many hundreds of thousands, so many millions, are meaningless. Of the trillions of words that have been uttered in the history of the College, so many with contrived gravitas, few ever hit their mark. But some, a few words in every life, a few syllables every academic year—they stick.

When Bradley entreated me to make the Rome trip, he uttered just such words. My life turned on a pivot when I heard them.

I did go to Rome. I learned how to recognize the four types of Pompeian wall painting, and I could tell in which century an Etruscan wall was built. I learned where to find good wine for less than 4,000 lire, and I made out with a girl from an FSP of another college. I walked to the Vatican every day, just to look at the Pieta. I learned how to smoke Gauloises, Bradley's chosen smoke— "French cigarettes with Turkish tobacco," he would say.

"By the end of this trip Rome will be your city," Bradley told us. "Rome is a walking city. Don't take cabs or buses- walk, and this city will be yours for the rest of your life."

So I walked. I learned how to drink coffee and wine, and I learned how to read a train schedule. I learned how to make spaghetti carbonara (illegally) in a hotel room with one pot and a camping stove. Every morning I went to the market in the Campo dei Fiore, every noon I got pizza or half a roasted chicken at Pizza Rustica ("Old Fashioned Pizza") and every night, around 11, I'd walk with my friends to Giolitti's for gelato that makes

American ice cream taste like Elmers glue.

Bradley took us to Ravenna, the mosaic capital of Early Christianity. He showed us pristine churches with little pieces of glass so blue that they seemed otherworldly. He took us to Florence and we climbed Brunelleschi's dome. He told us about the ingeniousness of its construction, how the two onion-peel-like layers meet and are held together, almost miraculously, at the oculus. We looked up at the mosaics in the Florentine baptistery as he walked us through every biblical scene, explaining the connections to the rite of baptism.

"Why are baptisteries octagons?" he asked.

Silence.

"How many people were on the ark?"

I counted in my head. "Eight?"

"That's right." Bradley smiled. "Eight were saved from the waters of the flood, so baptisteries are eight-sided to remind us of the association between water and salvation."

Back in Rome, at St. Peters Basilica, the truly holy moment took place. We met there in the morning. Bradley sat us down in the portico. It was the last lecture of the quarter, the end of our classes in Rome. He began by pulling out of his bag an 8-by- -10, glossy, black-and-white photo. It was of a plain New England Congregational church—austere, clapboard siding and plain, clear windows.

"This," he said, "is what is most valued in American spirituality. Simple, plain, nothing ostentatious." He went on to describe how our culture values a modest, humble faith—it's based on our Puritan past and the "Protestant work ethic." Then he swung around, his arm sweeping across the countenance of the grandest church in the world. He told us about Catholic sacramental theology, about the extravagance that runs in Mediterranean blood and about how the church had to make a statement to the worldly governments about where true power lay. Don't be judgmental, was his point; there are plenty of good reasons to build a church this big and beautiful.

Then, for the next two hours, we walked from the portico, through the piazza, into the basilica, through the side aisles, down the nave, under the dome and to the apse. There, an enormous empty chair, suspended from the wall, awaits its cosmic owner. Along the way he stopped and quizzed us on translations of Latin and Greek inscriptions, spoke of the sculptures and marble-inlaid floors, about the four massive piers that hold up the cupola and the holy relics ensconced therein, and the baldacchino that shelters the high altar. Every bit of that overwhelming structure Bradley explained with the passion of an evangelist. It was as religious an experience as I've ever had.

I wrote my final paper in Rome on basilican architecture. Bradley gave me an A with a citation—he wrote that my essay was "at times eloquent." I had never been called eloquent.

When I returned to Hanover I petitioned to become a classics major. My final six classes at Dartmouth were all in the department. I went from one of dozens of history majors to one of six classics majors. My proudest moment of graduation week was introducing my parents to Professor Bradley at the cocktail reception for classics majors.

Bradley will retire from reaching at Dartmouth this spring. His younger colleagues may wonder why he didn't make more of a mark on academia. Where are the award-winning books? The quotes in The New York Times and interviews on National Public Radio? Where are the kudos from the guild of Latinists upon his retirement?

I have an entirely different standard for measuring the man's career.

I'll raise a glass to my friend, Edward, at his retirement dinner. I'll thank him for driving me to the hockey rink, for challenging me to go to Rome, for reading scripture at my wedding, for praying for my children. I'll thank him for not chasing the brass ring of academic achievement. I'll thank him for helping me become a man.

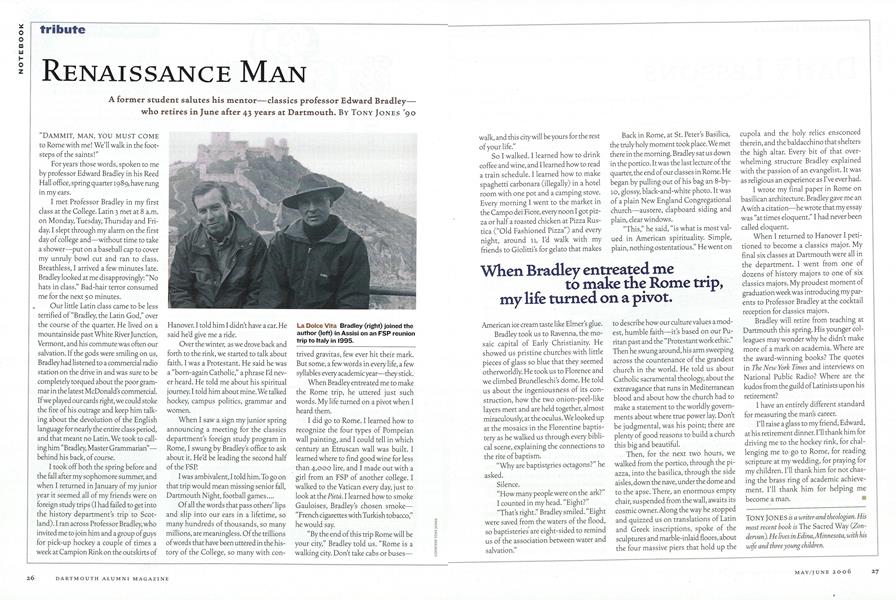

La Dolce Vita Bradley (right) joined the author (left) in Assisi on an FSP reunion trip to Italy in 1995.

When Bradley entreated me to make the Rome trip, my life turned on a pivot.

TONY JONES is a writer and theologian. Hismost recent book is The Sacred Way (Zondervan).He lives in Edina,Minnesota, with hiswife and three young children.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

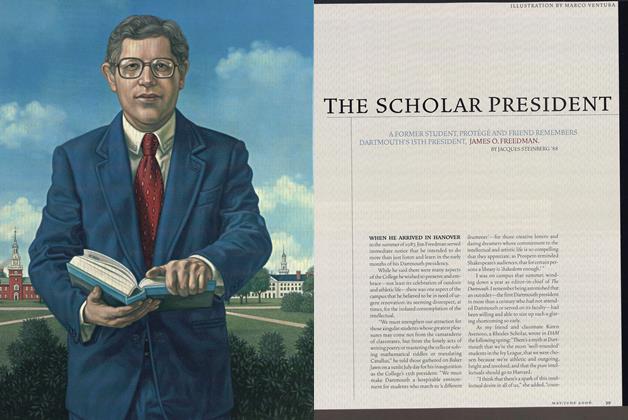

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May | June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

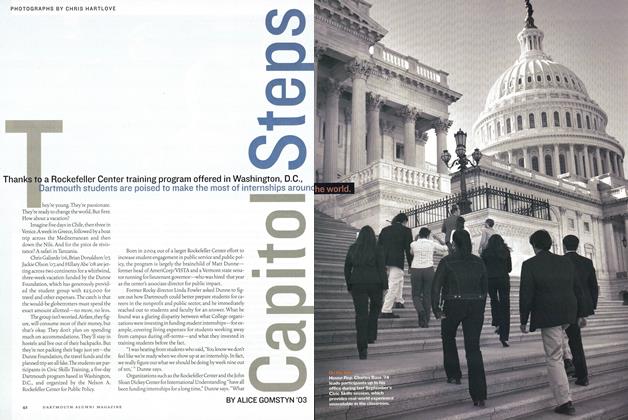

FeatureCapitol Steps

May | June 2006 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

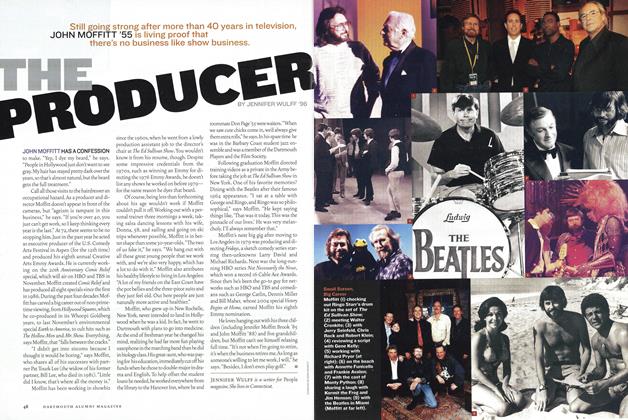

FeatureThe Producer

May | June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

Article

-

Article

ArticleSTATISTICS OF REGISTRATION

December, 1911 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1940 -

Article

ArticleFALL WRAPUP

JANUARY 1973 -

Article

ArticlePresident of the Year

JUNE 1973 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Award

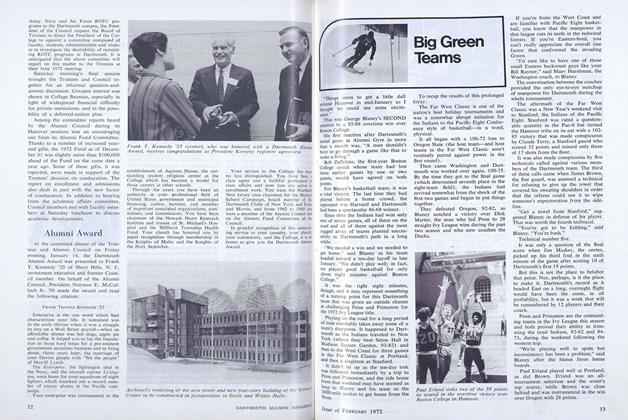

FEBRUARY 1972 By FRANK THOMAS KENNEDY '25 -

Article

ArticleA Sun-Powered Race Between Two Very Different Schools

December 1988 By Timothy J. Burger '88