River Hogs

Early 20th-century loggers braved no shortage of dangers to harvest timber from the Second College Grant.

May/June 2006 STEVE GORMANEarly 20th-century loggers braved no shortage of dangers to harvest timber from the Second College Grant.

May/June 2006 STEVE GORMANEarly 20th-century loggers braved no shortage of dangers to harvest timber from the Second College Grant.

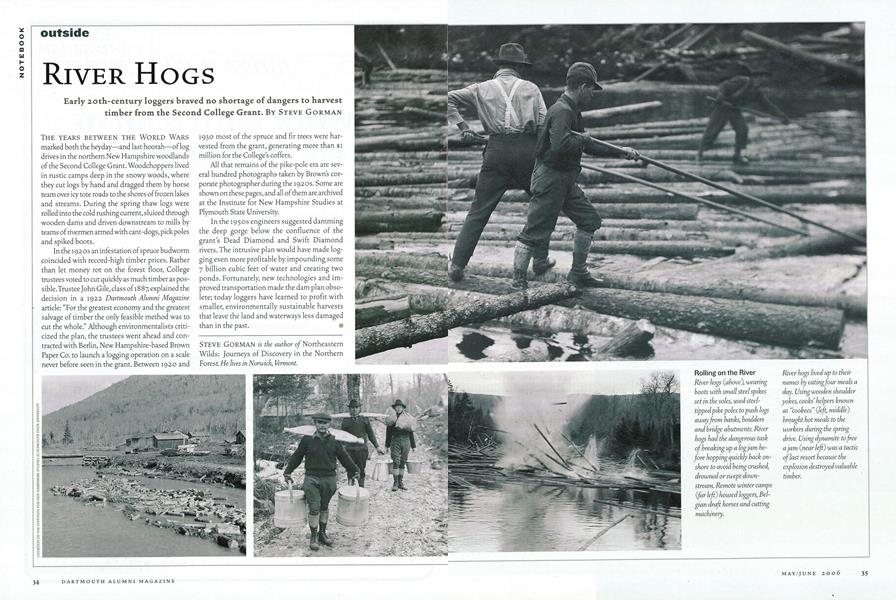

THE YEARS BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS marked both the heyday—and last hoorah—of log drives in the northern New Hampshire woodlands of the Second College Grant. Woodchoppers lived in rustic camps deep in the snowy woods, where they cut logs by hand and dragged them by horse team over icy tote roads to the shores of frozen lakes and streams. During the spring thaw logs were rolled into the cold rushing current, sluiced through wooden dams and driven downstream to mills by teams of rivermen armed with cant-dogs, pick poles and spiked boots.

In the 1920s an infestation of spruce budworm coincided with record-high timber prices. Rather than let money rot on the forest floor, College trustees voted to cut quickly as much timber as possible. Trustee John Gile, class of 1887, explained the decision in a 1922 Dartmouth Alumni Magazine article: "For the greatest economy and the greatest salvage of timber the only feasible method was to cut the whole." Although environmentalists criticized the plan, the trustees went ahead and contracted with Berlin, New Hampshire-based Brown Paper Cos. to launch a logging operation on a scale never before seen in the grant. Between 1920 and 1930 most of the spruce and fir trees were harvested from the grant, generating more than $1 million for the College s coffers.

All that remains of the pike-pole era are several hundred photographs taken by Brown's corporate photographer during the 19205. Some are shown on these pages, and all of them are archived at the Institute for New Hampshire Studies at Plymouth State University.

In the 1950s engineers suggested damming the deep gorge below the confluence of the grants Dead Diamond and Swift Diamond rivers. The intrusive plan would have made logging even more profitable by impounding some 7 billion cubic feet of water and creating two ponds. Fortunately, new technologies and improved transportation made the dam plan obsolete; today loggers have learned to profit with smaller, environmentally sustainable harvests that leave the land and waterways less damaged than in the past.

River hogs lived up to theirnames by eatingfour meals aday. Using wooden shoulderyokes, cooks' helpers knownas "cookees" (left, middle)brought hot meals to theworkers during the springdrive. Using dynamite to freea jam (near left) was a tacticof last resort because theexplosion destroyed valuabletimber.

Rolling on the RiverRiver hogs (above), wearingboots with small steel spikesset in the soles, used steeltippedpike poles to push logsaway from banks, bouldersand bridge abutments. Riverhogs had the dangerous taskof breaking up a logjam beforehopping quickly back onshoreto avoid being crushed,drowned or swept downstream.Remote winter camps(far left) housed loggers, Belgiandraft horses and cuttingmachinery.

STEVE GORMAN is the author of Northeastern Wilds: Journeys of Discovery in the Northern Forest He lives in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

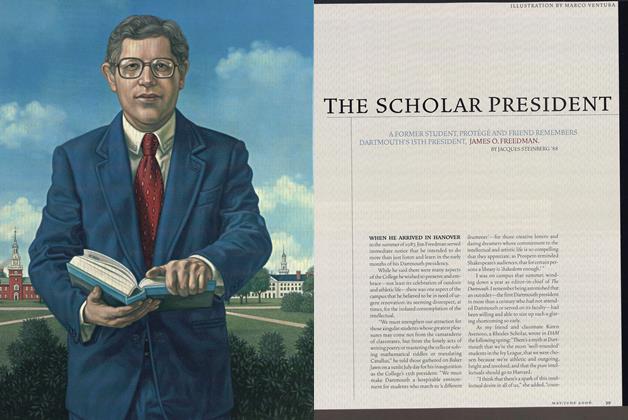

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May | June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

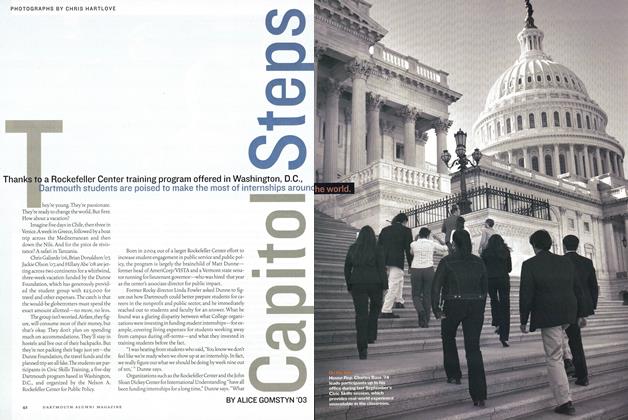

FeatureCapitol Steps

May | June 2006 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

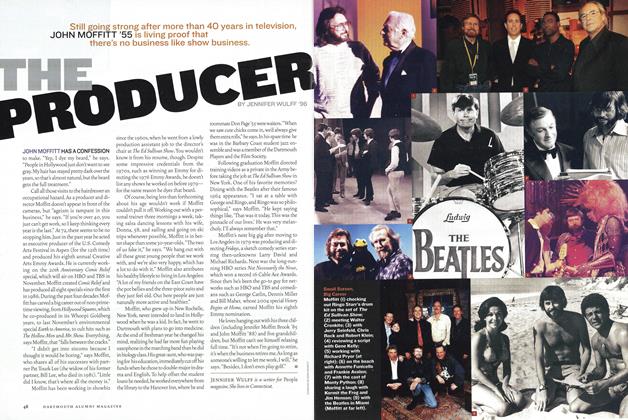

FeatureThe Producer

May | June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

OUTSIDE

-

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Creek Kid

MAY | JUNE By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEStill Trippin’

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By ED GRAY ’67 -

OUTSIDE

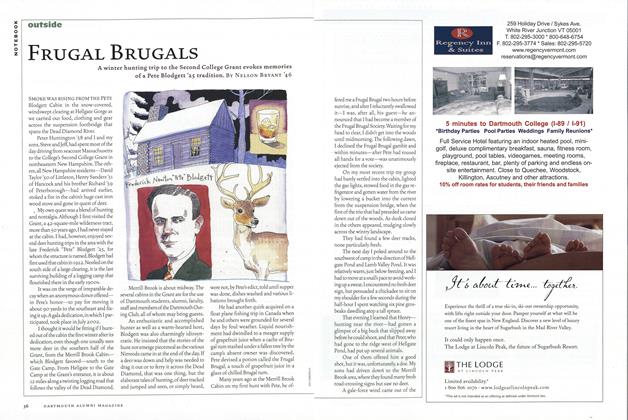

OUTSIDEFrugal Brugals

Nov/Dec 2003 By Nelson Bryant ’46 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDECall Me Kook

May/June 2011 By Peter heller ’82 -

OUTSIDE

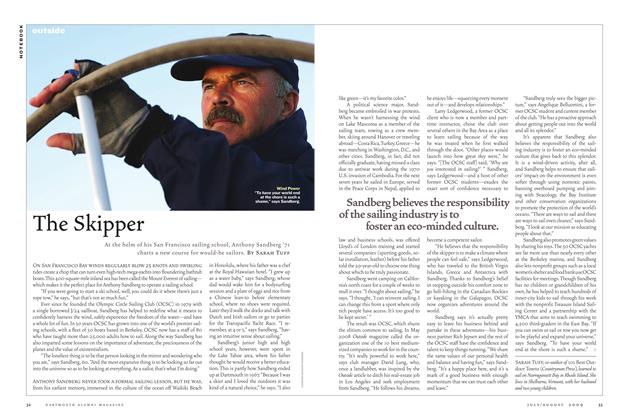

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July/Aug 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAnimal Attraction

Mar/Apr 2004 By Ted Levin