QUOTE/UNQUOTE: "Officers and employees do not always understand who sets institutional priorities and makes decisions...there is insufficient accountability around departmental and individual performance." FROM THE MCKINSEY REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ISSUED APRIL 25 AFTER THE FIRM'S STUDY OF THE COLLEGE'S ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE (WWW.DARTMOUTH.EDU/~PRESOFF/REPORT/SUMMARY.HTML)

WHEN THE COLLEGE BOARD informed Dartmouth that 57 applicants for the class of 2010 were among the 4,411 students across the country whose SAT tests were incorrectly scored too low—a story that made national headlines—each of the cases was reviewed but not a single decision changed. Most of the affected Dartmouth applicants had scores that were off by only 10 to 20 points, while a few may have gained 60 to 100 points when corrected, both in keeping with the national norm. The College Board says 83 percent of corrections on the 2,400-point test gained 40 or fewer points.

While some schools indicated the errors have forced them to reconsider the value placed on SAT scores, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid Karl Furstenberg says that Dartmouth still considers SAT a valid criterion. (Thirty-three percent of the class of 2010 will matriculate with a perfect score in either the math or verbal portion of the test.)

Schools with SAT-optional policies (among them Bates, Bowdoin and Mount Holyoke) are simply not as selective as Dartmouth, Furstenberg says. "We need all the information that we can possibly get to make decisions," he says. "The SAT is the only measure we have that is a standardized measure across the country and the world."

office works to assemble a portrait of a student that includes qualities such as leadership as well as academic preparation and potential. Standardized tests "supplement" the high school academic record. Dartmouth has no formula weighting any factor more than others, he says. Nonetheless, SAT scores remain only one of many factors considered during the admissions process, Furstenberg says a point underscored, he claims, by the recent scoring error. Furstenberg says his

Admissions officers consider scores against background factors such as whether a student is the first in a family to go to college, comes from an under-resourced high school or speaks a language other than English at home. National data on the socioeconomic and other biases of the tests have shown "you have to take the SAT scores with a very large grain of salt," Furstenberg says.

While the scoring problem has not convinced Furstenberg to do away with the SAT, he thinks it leaves the College Board with a credibility problem—especially among high school students for whom the test is so important. "It undermines confidence in something that should be 100 percent accurate," he says.

The College Board wants to assuage such concerns. Each answer sheet from last April's test was scanned twice, on two different days, by two different machines. Still, Furstenberg and other observers bet more high school students will ask for their tests to be hand scored. Two such requests for the October 2005 test eventually revealed the larger problem.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July | August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

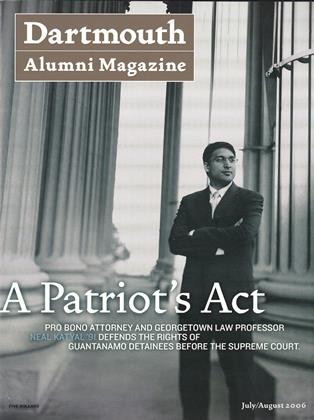

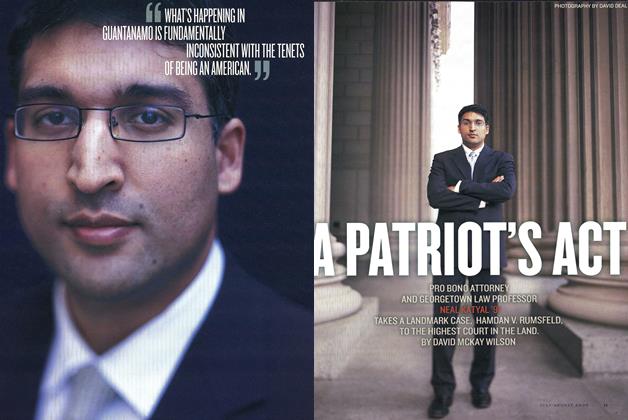

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July | August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

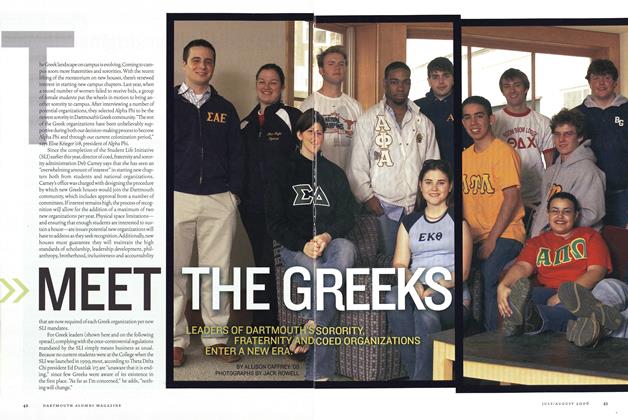

Feature

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July | August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMaking a Comeback

July | August 2006 By Lauren Zeranski ’02

Victoria McGrane '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOREIGN COMMENT ON PROFESSOR MOORE'S EDITION OF CICERO'S "DE SENECTUTE."

DECEMBER 1905 -

Article

ArticleD. O. C. WINTER CARNIVAL FILM RECORDS EVENTS

June, 1926 -

Article

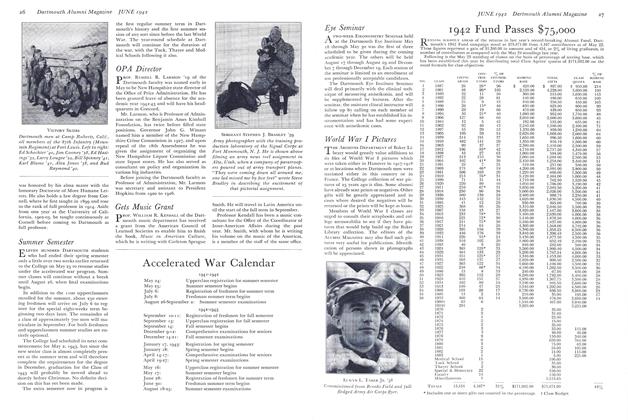

ArticleAlumni Trustee

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleAids Retarded. Children

February 1952 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

March 1981 -

Article

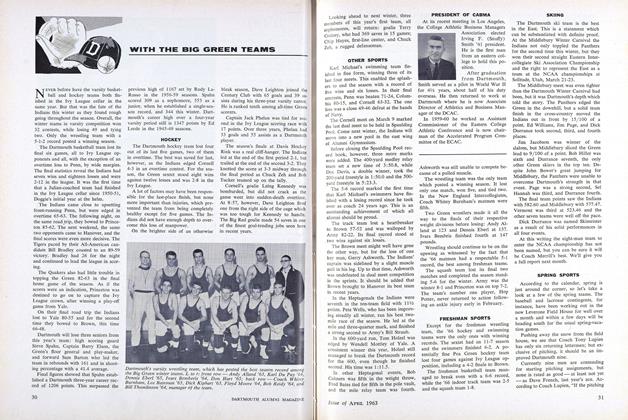

ArticleSPRING SPORTS

APRIL 1963 By DAVE ORR '57