QUOTE/UNQUOTE "[Sustainability Director Jim] Merkel should be tackling more obvious problems. The restrictions on kegs are a prime example. For every keg that is banned from a house, approximately 165 cans are used in its place." THE DARTMOUTH SUMMER EDITORIAL BOARD, WRITING IN THE DARTMOUTH, JULY 11

ERIC WINN '04 LEFT Dartmouth carrying more than $40,000 in student debt. He graduated, however, during a period of historically low interest rates and was able to convert the government-sponsored portion of his loans into a single fixed-rate loan at a 2.15 percent rate. "I couldn't have graduated at a better time," he says.

Students just now borrowing for college undoubtedly agree. Recent changes to federal student loan programs—the largest source of education loans—have ended the opportunity to consolidate and lock in low rates. Now interest rates are fixed for the life of the loan, and the new 8.5 percent rate is no bargain. These changes occur as student debt levels are already on the rise.

Students are increasingly taking on private loans in addition to federal loans that come as part of a financial-aid package, says Sandy Baum, a senior policy analyst for the College Board. She credits the rising student debt burden to college costs that jump about 6 percent a year while family incomes and savings rates stagnate.

Dartmouth is fighting rising student debt with more generous scholarship aid funded from its own coffers. While Princeton —which in 2001 eliminated all loans for students who qualified for financial aid—has been credited as being at the forefront of this effort, Dartmouth has increased its scholarship budget 399 percent since 1986 to address higher costs.

The College recently acted to further ease the loan burden for students from the lowest-income brackets. Starting with the class of 2009, students with family incomes less than $30,000 are no longer asked to take out loans as part of the financial aid offered by the College. Students with family incomes of less than $45,000—there are 457 of them currently on campus—are also fully funded by the College for their first year.

These efforts do not mean students from the lowest-income levels won't have to borrow any money. There are still costs for computers, foreign study programs and other extras. "Our goal," says financial aid director Virginia Hazen, "was that they could graduate with a total loan that would not be more than what the highest-income students graduate with." In addition to being need- blind when making admissions decisions, Dartmouth pledges to meet each students full need. Fewer than 7 percent of 1,500 schools surveyed by Thomson Petersons, a publisher of education data, do this.

Hazen's staff develops aid packages with two different analyses. One uses the formula that determines eligibility for federal funds; the second, which determines a students need for Dartmouth funds, employs a formula involving family size, number of kids in college, the amount the family earns and its net worth, Hazen says. Her staff also considers special circumstances, such as high medical bills, to judge how much a family can contribute. Once family contribution and "self-help" funding from federal loans and on-campus employment are projected, the Colleges aid is determined. The College does not automatically ask a student to borrow the maximum available from the government.

The percentage of students needing Dartmouth scholarships has increased steadily over the decades since the College promised to meet any student's needs: from 30 percent in 1974-75 to 43.1 percent in 2004-05. Hazen expects that nearly 47 percent of the incoming class of 2010 will receive aid from various sources.

The College's need-blind, full-need policy relies on a healthy endowment. "That is what will protect need-blind admissions and meeting the full need," says Hazen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

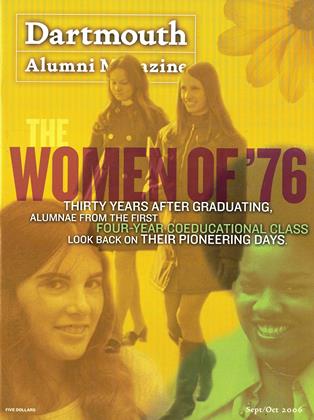

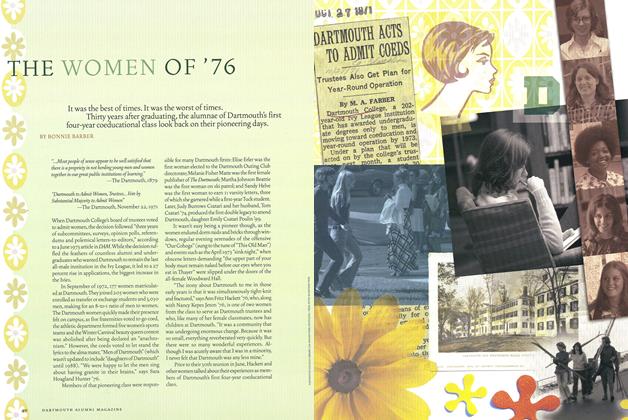

Cover StoryThe Women of ’76

September | October 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

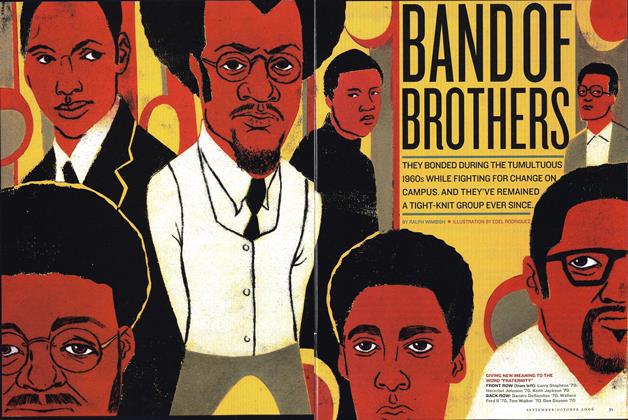

FeatureBand of Brothers

September | October 2006 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

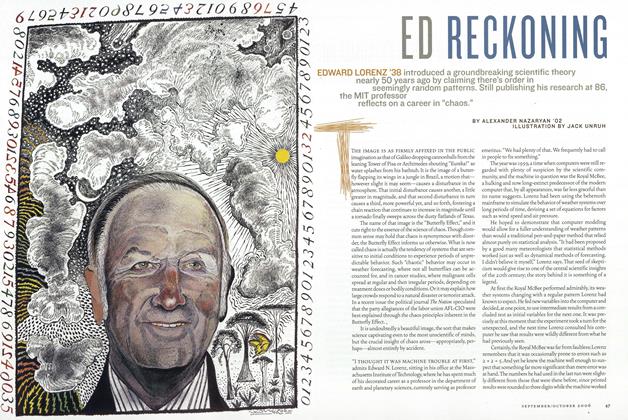

FeatureEd Reckoning

September | October 2006 By ALEXANDER NAZARYAN ’02 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2006 By Russell Hardy' 62 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2006 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SPORTS PUBLICITY -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

September | October 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88

Victoria McGrane '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleSEASON'S MUSIC PROGRAM ONE OF GREAT VARIETY

November, 1025 -

Article

ArticleFred Howland '87, Trustee Emeritus

May 1953 -

Article

ArticleBarbary Coast to Play At Meadowbrook Nov. 21

November 1953 -

Article

ArticleA CIVIL WAR STUDENT

February 1945 By EDWARD CHASE KIRKLAND '16 -

Article

ArticleWho Wauls to Be Right?

JUNE 2000 By Jen Whitcomb '00 -

Article

ArticleWhat Is "New" in the Program?

May 1958 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28