The constitution blunts theability of petition candidatesto rise to the board.

Since 1891 Dartmouth alumni have had the power to elect half the board of trustees directly and the other half indirectly. It is not a power they have exercised jealously. Mostly, what passed for an election was an anointing by a nominations committee; often there was only one candidate, and no ballots were mailed to the alumni whose duty it was to choose. That was not the way the system was supposed to work.

The way the game was played changed in 1980, when John Steel '54 gathered petitions to qualify for a place on the ballot and won. This immediately precipitated an attempt to overturn the election; led by chairman Sandy McCulloch '50, the trustees bid the alumni association to investigate for "any irregularities" and determine whether the election result "should or should not be affirmed." After both sides hired lawyers, Steel finally took his seat. Yet this did not settle the issue. With the encouragement of President John Kemeny, some trustees and alumni officers explored various alterations to lessen the likelihood of victory by another independent petition trustee candidate including outright elimination of the petition route—but eventually the "something must be done" movement satisfied itself with campaign restrictions and a doubling of the number of petitions required to qualify. The higher barrier proved impermanent, however. In 2004 T.J. Rodgers '70 ran as a petitioner and received 55 percent of the vote. The next year two more petitioners, Peter Robinson '79 and Todd Zywicki '88, overcame a nasty campaign against them to win in a complicated election procedure. Anxieties within the inner circle that has counted on a docile alumni body once again soared.

The alumni governance task force (AGTF) constitutioin being vigorously promoted is still another, and more concerted, "reform" designed to impede election of petitioners as alumni trustees by regaining control over the process. You have been—and will be told otherwise, but this is the truth.

The most forceful evidence lies in Article VII. In an earlier draft the AGTF repeated the ploy used since Steel's election to hinder unofficial candidates: It increased the number of petitions required to qualify—this time by a third. When protests arose the AGTF insisted that this higher number was necessary to legitimize a candidacy because of growth in the size of the alumni association. But in the latest draft, suddenly, the required number has been cut in half. Why? A newfound passion for the petition option? Hardly.

The obvious answer is that the AGTF hopes to multiply petition candidates and thereby divide the anti-establishment vote. Because splitting the opposition still leaves too much at risk, the AGTF has introduced a clever scheme. Petition candidates must obtain official petition forms from the nominations committee (NC) 30 days before the NC announces its one or two candidates. This prior notification makes it easy to game the system. Article VII requires that there be at least two candidates on the ballot. Thus, if there is no petition candidate, the NC will run Tweedle-Dum and Tweedle-Dee—one safely a photocopy of the other. If there is more than one petition candidate, the petitioners will split the opposition, virtually insuring that the NC's single candidates will win. Even if there is only one petition candidate, the NC still can gain the advantage by nominating, as its second candidate, someone who will attract some of the same support as the petition candidate. Indeed, the advantage is all the greater because, under the special rules that come into play when there are more than two candidates in the field, voters can cast ballots for as many, or as few, candidates as they wish. Under those conditions, the odds in favor of the "house" rise dramatically.

If the AGTF was honestly seeking to "increase choice," as it claims, it would nominate a fixed number of candidates. All candidates would be announced simultaneously, and there would be no reason for reducing the period for collecting signatures. The petition candidates could issue their own petition forms, and the election rules would be the same regardless of the number of candidates.

Article VII clearly illustrates that the AGTF constitution is not at all the instrument for broader participation and inclusiveness that it advertises itself to be. Indeed, it is exactly the opposite: a means of shuffling control of the association among an inner circle that never engages gears to drive any significant purpose. Yes, the proposed constitution will generate a spate of elections every year, but no provision serves to make these elections about anything. A liaison board would be created to communicate to the board of trustees, but what, specifically, is it designed to communicate? And what happens after something is communicated? The association would have three presidents—with a fourth always next at bat—and each would serve a one-year term in a particular, very limited role. Is this a formula for leadership-or is it an engine for fecklessness? An assembly is presented as the arm of the association, but it takes very little examination to realize that this new body is really the old council of old boys, male and female, and although it contains more elected representatives, its scramble of constituencies and purposes makes it unrepresentative of the majority of alumni.

The most unrepresentative portion, by design, is the delegation from the affiliated groups—alumni organizations defined by race or sexual preference. Qualification, as stipulated by the College, depends on whether a group has been historically "marginalized." Thus, leverage on questions dealing with Dartmouth would be awarded as a form of restitution for societal injustice. This not only seems a strange principle to invoke but also a measure calling for a calculus too complex to determine. The five groups certified at present patently fail to accommodate all of even the most obvious objects of discrimination. One has to wonder how large an assembly would be required to distribute electoral compensation on an equitable basis. And whether, like the apartheid legislature it mimics, it is finally a good idea.

At no time in American history has academe been in greater need of independent judgment as to its course. Vital involvement of the alumni offers a means of furnishing it. The AGTF constitution, however, is a fraudulent response to that need. Its defeat is the imperative first step toward restoration of the alumni to their historically intended role. IS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

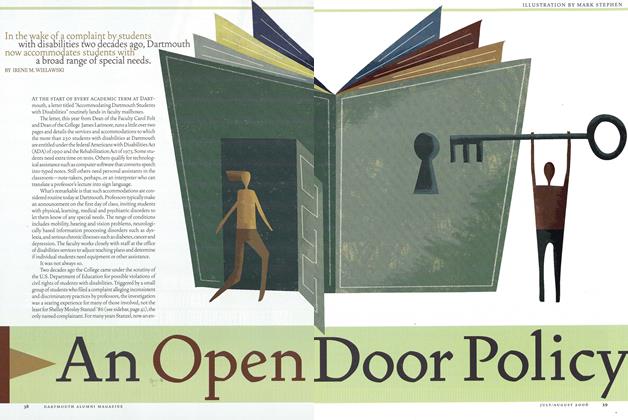

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July | August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

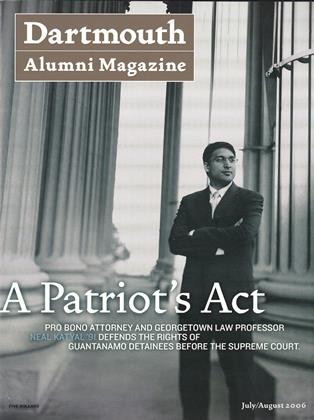

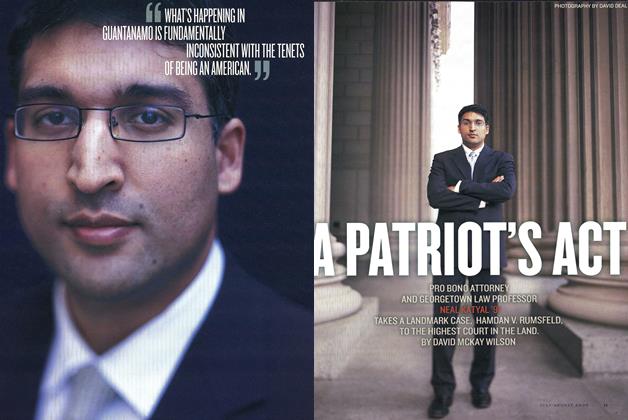

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July | August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July | August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMaking a Comeback

July | August 2006 By Lauren Zeranski ’02

Frank Gado '58

Article

-

Article

ArticleRICHARD GODDARD '20 TRAVELS WITH MACMILLAN

August, 1923 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

November 1950 -

Article

ArticleA Treasured Frost Item

OCTOBER 1962 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for —

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleOther Sports

November 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1949 By W. J. Mulligan '50