MANAGING DIRECTOR, "THE ECONOMIST

THE subject we have been instructed to speak on today is "What Are the Great Issues of the Anglo-Canadian-American Community?" There is hardly anything that happens in the world that is not an issue of the ACA community. We share so many of our problems - from Asian flu to the educational value, or the reverse, of television. Just offhand, there's only one problem you have that I can think of that we don't. There is no poison ivy in Great Britain. But not all of those are great issues, and we're invited to select, to identify the great issues.

Weil, in thinking on this question, it seemed to me that I could most usefully employ my few minutes in a few reflections on the greatest issue, on the supreme issue of the ACA community, the one which, although it is supreme, it seems to me we tend to take far too much for granted. It is, I think, the underlying assumption of this convocation and in particular of the question that has been set for discussion this morning. It is the underlying assumption that if we can identify the great issues, if we can dissect them and understand them, then we, our three countries and those that march with us, intend and will be able in some measure to move towards the solution of those issues together - that we shall not revert to the old practices of dealing with our problems in ignorance, in isolation, and in indifference. That, it seems to me, is the assumption underlying all of what we are discussing here this week. And I want to examine it because, I think, like so many assumptions it could come unstuck. It's astonishing how quickly one can move from the miraculous to the platitudinous, how within a very short space of years what was impossible becomes fact and is then regarded as obvious.

We have had a miracle in these ten years of the Great Issues Course. It is worth reminding you that when the Great Issues Course started in 1947 there was no North Atlantic Treaty, and there was no Marshall Plan. I remember very clearly engaging in an argument in the closing days of the war as to what continuing mechanisms and habits of alliance it was possible to hope for in the postwar era, and coming to the conclusion - not only myself but everybody engaged in that discussion - that one could hope for very little. Certainly it didn't seem at all likely in 1945 that we should have a North Atlantic Treaty of alliance or a Marshall Plan, or a continuing program of economic aid from the United States. Yet it has happened and now we take it for granted that it will continue.

The two misconceptions that I have in mind are these. First of all we tend, looking backwards, to assume that this way of conducting our affairs, which for the sake of brevity I will call simply the Alliance, was the natural and obvious application of the clear lessons of the war. I think we have all got into that habit of mind. We found out during the war that we had to act together, so we decided we'd go on doing so. But that is not so. At the end of the war the mechanisms and the habits of alliance were dismantled, as some people thought, with indecent speed. There was even a time, it seems fantastic to recollect, that there was a period immediately after the war when gravest apprehensions were felt in London whether we might not be seeing the first stages of a diplomatic alliance between Washington and Moscow against London. There was nothing obvious about the creation of the alliance, nor was it the result of positive and rational discussion. It was not the result of a meeting of minds, of saying clearly it is a good thing that we should form what I call the mecha- nisms and the habits of alliance and therefore we will do it. That didn't happen either. Mr. Douglas gave us yesterday a number of excellent reasons why we should work together. All of them are perfectly sound save that in matters of politics decisions are not taken, very rarely taken, on rational grounds. Certainly it was so in this case. No, we owe the alliance neither to wartime experience, nor to rational analysis; we owe it to fear and to anger. What restored the wartime mechanisms in 1947 and the years afterward was fear of Soviet aggression. The great architect of the alliance was Joseph Stalin.

As one looks back, it is astonishing how frequently Marshal Stalin came to the rescue of the Western community. Whenever the alliance seemed to be limping, whenever there were difficulties, whenever the capitals were drifting apart, with an uncanny sense of timing, and with perfect effectiveness, the Russians would always do something that would drive us together. Whether they are still doing it today is one of the questions one asks oneself. . . . The relationship between our countries is not a stable equilibrium. We are being pushed into this position by external force, and the question, the supreme issue to me, is whether when that external force is removed the equilibrium will remain.

I want to mention some of the apprehensions I have of some other forces that may push us apart. First of all, there seems to me to be a risk that what I am calling the Alliance - and I would remark again in passing that I mean something both less precise and much broader than the dictionary meaning of that word when I use it - may suffer from the steady erosion of domestic politics in all our countries. Open opposition to the alliance is astonishingly small in any of our countries. There is less of it than there was ten years ago. Virtually every public man in every one of our three countries if asked to answer the direct question whether he was in favor of the alliance would say "Yes" and mean it. Nevertheless, each of us in our own way, concerned with our own domestic politics, is constantly doing things that eat away at the base of the alliance. My most obvious and recent example is taken from the politics of my own country. I'm not going to go into the extraordinary mixture of diplomacy, emotion, jealousy, fear, apprehension, and other emotions that went into the unfortunate results of last autumn. But the way things turned out, it was necessary as a matter of domestic politics to have a scapegoat. The scapegoat was found in the United States, and the politicians of my country seemed to me for a period which is now happily coming to an end to be unforgivably reckless in the way in which, for their own immediate political concern, they took risks with the base of the alliance. I'm not denying that there was cause for some resentment and irritation, but I believe that the mechanisms of internal politics blew up passing irritation into something that could be regarded as being a serious wave of discontent, so serious that the artist who composed the admirable heraldry that is hanging behind our heads as a symbol of our purpose here found it necessary to depict the Lion turning his back on the Eagle and the Maple Leaf. . . .

I've taken my example from Great Britain. I could have done so from Canada where at this moment the relationship of Canada to the United States is at the center and forefront of domestic politics, and where also, I fear, there will be a great deal of articulation on the things that divide and of silence on those that unite. Or in the United States where, it seems to me, the normal constitutional position is now being restored, where the great doctrine, the great pernicious doctrine, of the separation of powers which has been suspended more or less for the last twenty years or so is resuming its sway and we are going back to the normal position in which the world's strongest power has a divided government. There too, I fear, one of the casualties, unless we take care, is going to be the base of the alliance in which we all believe.

There are economic dangers. Mr. Randall has touched on them. I am myself profoundly skeptical about our ability to control the economic climate. One of the great myths of the present age is that we have conquered the trade cycle, that we can make ourselves just as prosperous or depressed as we wish. I don't believe it. I don't believe that we know half as much as we think we do about how to control the climate, and some day we're going, again, to have years of slack tide. Then, precisely because of all the boasting about our ability to control, the politicians in each country will be under the heaviest pressure to produce results at once. Unless we take steps beforehand to rule it out, the easiest step they can take will be to try to export the depression to others. That, if I were a Canadian, would be a matter of the greatest apprehension to me - lest at some future time, in return for all those depressions of weather you get coming down from Canada, there may be some return of an economic depression sent up to Canada.

Then there is another economic problem which seems to me to have in it the seed of considerable dissension between us. Somebody once said that living with the United States is rather like sharing a loose box with an elephant. In an economic sense, it's worse than that because we're in the loose box with an elephant that is rapidly growing in size. For countries which do not share the superabundant economic dynamism of the United States, to have to live with you in the same loose box is at times an uncomfortable experience. I have always maintained, since long before the war, that what is called "the problem of the dollar" is not a temporary awkwardness; that it is an organic difficulty when the economic constitution of the countries of the world in the twentieth century is such that you have this one so strong, so wealthy, that there are no free means by which the rest of the world can balance its payments with the United States; that there is bound to be to some degree a network of restrictive, discriminatory protections against the sheer strength of the United States.

Now hitherto in the twelve years since the end of the war we have been very successful in preventing this economic discrimination which all the non-American nations of the world practice against your goods from poisoning political relationships. But I have a suspicion that that has been possible only because we have been living through prosperous years, and that if at some future time trade becomes less prosperous than it is now, these inevitable discriminations are going to have unfortunate political reactions.

One could go on with other ways, but, perhaps, I have sufficiently made my point: that there are forces which instead of pushing us into the equilibrium that we are now in, thank God, will be pulling us apart. We cannot always rely on the intervention of Joseph Stalin.

As Mr. Randall said, and it's a great comfort to me, our job this morning is to identify issues and not to solve them. But I want to say just one word on this problem, this issue that I have raised. How do we keep the equilibrium? I think we can by understanding what it is that brought it about, by being articulate about the underlying premises and not taking them for granted. If we can't somehow work out a statement of the essential basis of alliance, pure "hands across the sea" stuff and the rest about undefended frontiers and a common cultural heritage won't carry us very far.

On the other hand, to the other extreme, I would myself, with all respect for the devotion and the enthusiasm of the people who think differently, think it a waste of time and effort to attempt to construct elaborate, federal constitutions for our community. But somewhere between those extremes, between the pure platitude and the constitutional document, it ought to be possible to construct a statement of the essential bases, which seem to me to be a list of those things that we are going to try to do together and those things that we are going to do in isolation. If we can do that and can construct, so to speak, a litany, and say it every day, and teach it to our children, until what has been the accident of Soviet pressure is replaced by a positive faith in the absolute necessity of a continuance of community, then, I believe, that is the line on which we might solve this issue, that we might in time be granted by God's grace what we now take for granted, and that instead of the negative base of fear that brought us together we could have a positive faith and conviction that would prevent us from pushing any of these things, domestic policies, economics pressures or the rest, to the point where they endanger the basic principles on which we hope to proceed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

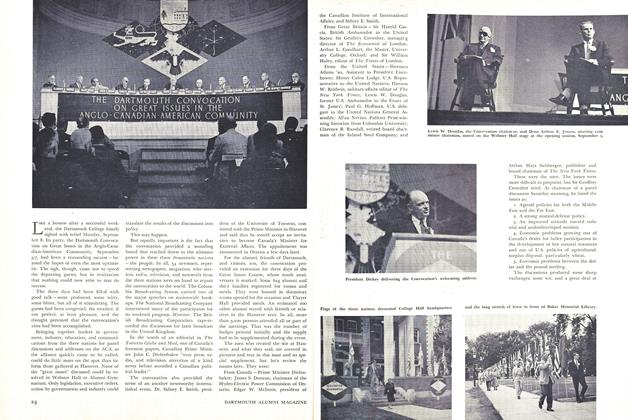

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1957 By ALLAN NEVINS

SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER

Features

-

Feature

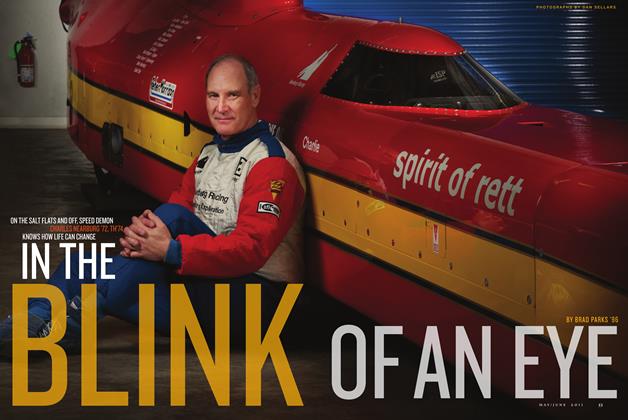

FeatureIn the Blink of an Eye

May/June 2011 By BRAD PARKS '96 -

Feature

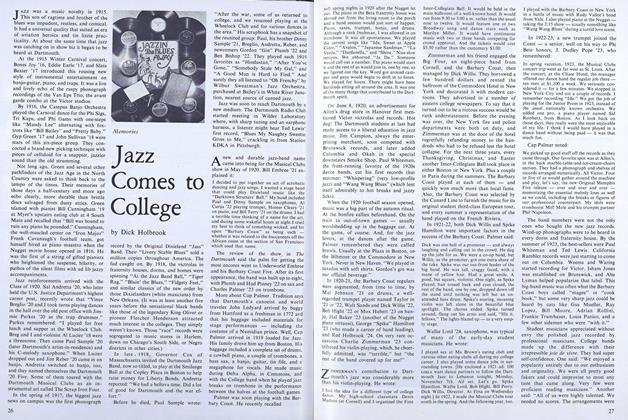

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

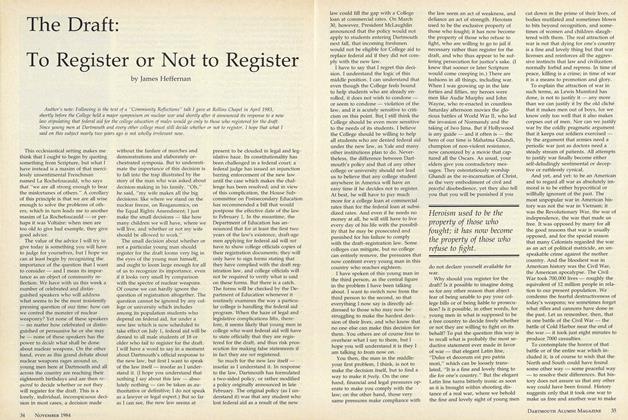

FeatureThe Draft: To Register or Not to Register

NOVEMBER 1984 By James Heffernan -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1972

JULY 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

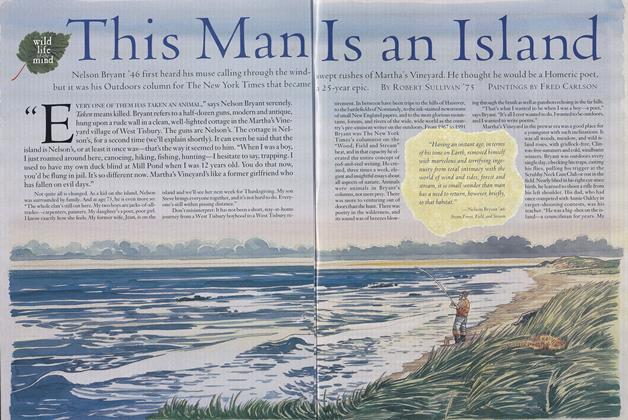

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureCarnival Art

Nov/Dec 2010 By STEVEN HELLER