The Pursuit of Happiness

Years after recovering from the depression that darkened his student days, a teacher tries to pass along the humanity he found in Dartmouth’s classrooms.

May/June 2007 Daniel Becker ’84Years after recovering from the depression that darkened his student days, a teacher tries to pass along the humanity he found in Dartmouth’s classrooms.

May/June 2007 Daniel Becker ’84Years after recovering from the depression that darkened his student days, a teacher tries to pass along the humanity he found in Dartmouth's classrooms.

I DECIDED TO ATTEND DARTMOUTH AT THE AGE OF 11, WHILE VISITING THE campus for my dad's 25 th reunion. I spent most of the time in the Kiewit computer center with undergraduate guides who showed us all the cool things we could do on the schools state-of-the-art computer. One day I learned how to use the giant dot-matrix printer to produce an oversized banner of my name. I can still recall the pocking sound of the printer head banging against the slack roll of brown paper as my name magically took shape out of random rows of letters and numbers. I brought the banner home to San Francisco, a private contract between me and my future alma mater.

Another reason that reunion was so special was the presence of my mom. Eight years earlier, when I was only 3, Mom had first been diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, a disorder so rare at the time that no adequate treatment was available in San Francisco. She spent four of the next eight years at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, a thousand miles from home. She had recently been released from her second stay there, and her presence at the reunion seemed to confirm that we would finally return to being a normal family.

By the time I was accepted to Dartmouth, seven years later, her illness was again evident. Perhaps as a result of the strange situation at home or perhaps from the normal pressures of adolescence, I began to suffer from an increasingly debilitating depression. I felt like a tri-athlete I had once seen on Wide Worldof Sports who, approaching the end of the race, collapsed and crawled over the finish line. I had cast out my college applications like grappling hooks, hoping to gain purchase somewhere that would rescue me from my unhappiness at home. Perhaps this was too much pressure to put on any college—or myself.

The excitement of the new carried me forward through my first few months in Hanover. I was assigned to a triple room on the third floor of Richardson with its own fireplace and bathroom. My two roommates couldn't have been nicer. There was always something going on. I loved my freshman seminar on Utopias and dystopias and having my workout clothes washed and waiting for me each day at JV soccer practice.

But as the weather turned in mid-October and the smell of wood smoke mixed with the sharp, cold and dulling light, my mood likewise darkened. Suddenly the upbeat spirit that my classmates seemed to ooze—"Isn't this place great? Don't you just love it here?"—left me feeling more and more isolated.

I remember the first evening it snowed, when everyone ran outside to pelt the residents of the women's dorm next door with snowballs or to catch a ride on the icy ground by grabbing onto the fenders of passing cars. I remember wondering how, surrounded by so much happiness, I could feel so sad and alone.

The inner voice that had become my companion in high school—"What's wrong with me? Am I going crazy?"—returned, and its presence seemed to confirm that I had reached the end of hope.

On Christmas break I admitted for the first time to my parents that I was depressed. They encouraged me to see a psychiatrist, but I did not have enough time to make much progress. I returned to Hanover in early January feeling despondent and suicidal. After a week of lying in my bed I somehow managed to gather my belongings and return to San Francisco. Three months of intense therapy ensued, in which my therapist urged me to recognize that what was going on with my mom was not normal and it was understandable that it would lead me to feel depressed. At one point he posed a seminal question: Could I ever allow myself to feel happier than my parents? His words helped to create a crack in the unrelenting gloom and let me consider moving on with my life. My goal had always been to return to Dartmouth as soon as possible. The therapist probed whether that was such a good idea. "Why don't you consider Reed College?" he asked. "Everyone there is depressed."

But I had already made Dartmouth the vessel for my hopes for normalcy. My mood having somewhat improved, I returned for the spring quarter. I'd like to say that everything was different upon my return, but that would be fiction. It was not easy to be at Dartmouth and express any ambivalence about the College. Either you loved it or there was something wrong with you. As if I needed any further confirmation that something was wrong.

The College did, however, provide some great opportunities for restless spirits. I spent the spring of my sophomore year in an Outward Bound program where I lived in a house with 10 other students and two Outward Bound instructors. We spent weekends exploring the mountains and lakes of New Hampshire. Thanks to the Dartmouth Plan, I spent fall and winter of my senior year in London, where I interned with a member of Parliament and developed an interest that led to a career in public policy.

Where I really found refuge at Dartmouth was in the classrooms. Not only did my professors show me that it was okay to be intellectual, they also revealed to me their humanity. I remember professor Michael Dorris not only helping me to see American history from a Native American perspective, but also turning from the board once during summer quarter to share with the class how he had prepared that day's lecture the previous afternoon while sitting in a stream.

I recall professor Charles Wood, a renowned medievalist, telling the class how he and several colleagues had recently celebrated the 1,000 birthday of a famous Gothic architect by sharing a birthday cake in his honor. "We medievalists can be a little odd," he added as an afterthought.

EIGHT YEARS AFTERI GRADUATED MY mom finally succumbed to her anorexia. Only many years after that did I begin to experience what life could be like out from under the pain and sorrow of her illness.

I have always remained ambivalent about my Dartmouth experience. It could not rescue me from my own unhappiness, and I guess at some level I have always blamed it for that. Only with the beauty of perspective can I now see that it was an unrealistic expectation to put on the College.

In 2005 I changed careers and became a high school history teacher. Every day I stand in front of a group of 15- and 16-year-old students who regard me with a mix of boredom, curiosity and whatever results from the unpredictable consequences of hormones. Thanks to my own experience, I realize that many of them have difficulties in their lives that might interfere with their ability to devote themselves to the school or the classroom. For the brief time I have their attention, I often find myself trying to channel to them the humanity, passion and unembarrassed love of learning that my Dartmouth professors passed on to me.

For many years I thought about what Dartmouth didn't do for me. Now I'm glad to focus on what it did.

"I remember wondering how,surrounded by so muchhappiness, I could feel so sad."

DANIEL BECKER chronicled his experienceof growing up with an anorexic mother in This Mean Disease (Gurze Books, 2005). Heteaches social studies at Interlake High Schoolin Bellevue, Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

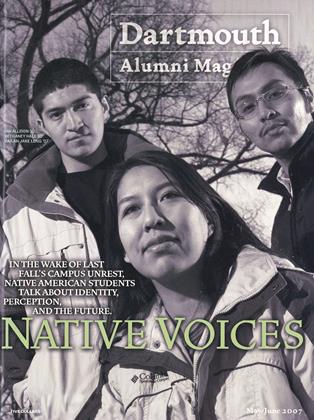

Cover StoryNative Voices

May | June 2007 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05 -

Feature

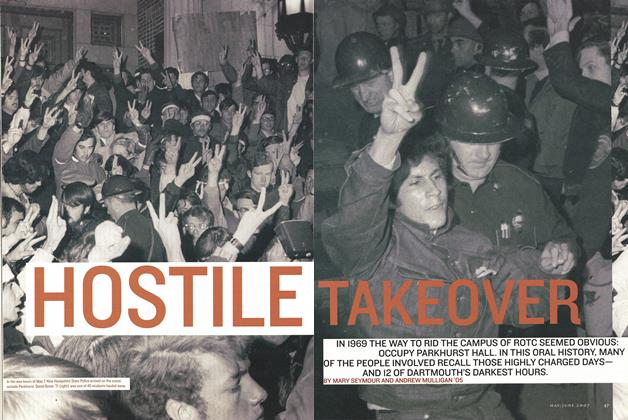

FeatureHostile Takeover

May | June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

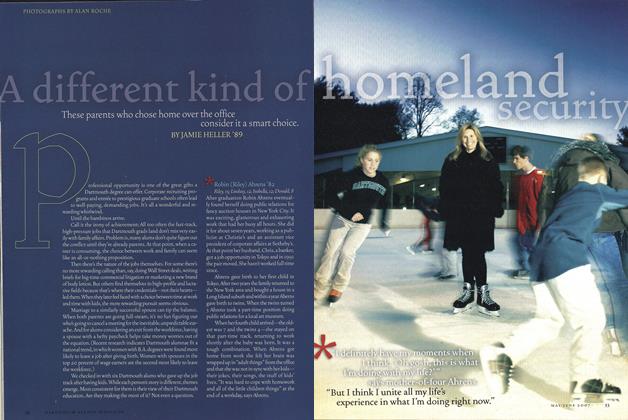

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May | June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2007 By BONNIE BARBER

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

MAY 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe “Happy” Swindler

May/June 2011 By John Grossman ’73 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYDaily Lessons

May/June 2006 By Ken Roman ’52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

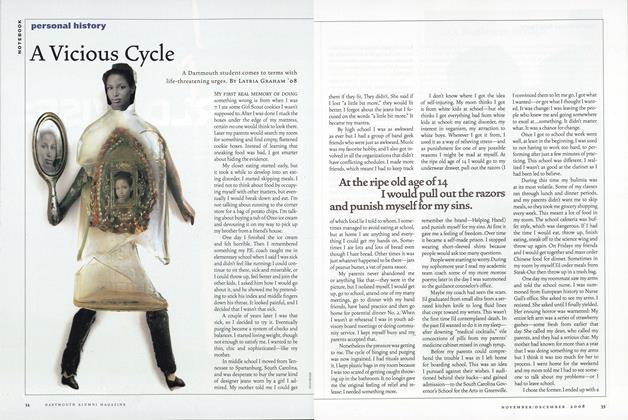

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

Nov/Dec 2008 By Latria Graham ’08 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBeyond Words

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By ROSALIE LIPFERT ’13 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYChasing Pollock

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By SAM SEYMOUR '79