A Different Kind of Homeland Security

These parents who chose home over the office consider it a smart choice.

May/June 2007 JAMIE HELLER ’89These parents who chose home over the office consider it a smart choice.

May/June 2007 JAMIE HELLER ’89These parents who chose home over the office consider it a smart choice.

Professional opportunity is one of the great gifts a Dartmouth degree can offer. Corporate recruiting programs and entree to prestigious graduate schools often lead to well-paying, demanding jobs. It's all a wonderful and rewarding whirlwind.

Call it the irony of achievement: All too often the fast-track, high-pressure jobs that Dartmouth grads land don't mix very easily with family affairs. Problem is, many alums don't quite figure out the conflict until they're already parents. At that point, when a career is consuming, the choice between work and family can seem like an all-or-nothing proposition.

Then there's the nature of the jobs themselves. For some there's no more rewarding calling than, say, doing Wall Street deals, writing briefs for big-time commercial litigation or marketing a new brand of body lotion. But others find themselves in high-profile and lucrative fields because that's where their credentials—not their heartsled them. When they later feel faced with a choice between time at work and time with kids, the more rewarding pursuit seems obvious.

We checked in with six Dartmouth alums who gave up the job track after having kids. While each persons story is different, themes emerge. Most consistent for them is their view of their Dartmouth education. Are they making the most of it? Not even a question.

Robin (Riley) Ahrens '82 Riley, 15; Lindsay, 12; Isabella, 12; Donald, 8

After graduation Robin Ahrens eventually found herself doing public relations for fancy auction houses in New York City. It was exciting, glamorous and exhausting work that had her busy all hours. She did it for about seven years, working as a publicist at Christies and an assistant vice president of corporate affairs at Sotheby's. At that point her husband, Chris, a banker, got a job opportunity in Tokyo and in 1991 the pair moved. She hasn't worked full time since.

Ahrens gave birth to her first child in Tokyo. After two years the.family returned to the New York area and bought a house in a Long Island suburb and within ayear Aherns save birth to twins. When the twins turned 3 Ahrens took a part-time position doing public relations for a local art museum.

Part of the problem was the half-time nature of the work. When you're working part time, "sometimes you feel like you're not good at anything," says Ahens. "Whether it's sports or academics or having fun, Dartmouth people give 100 percent, and I wasn't used to giving less than 100 percent."

The turning point came on a winter-morning run before work when she considered what she really wanted to be good at during this point in her life. "I realized what I really wanted to be good at was raising these kids," she says.

With the support of her husband and children she gave up her job. In the intervening years she's found places where her interests and her children's coincidecoaching power skating and lacrosse and teaching yoga and poetry seminars in her kids' school.

Not that it's a perfect setup. Her husband commutes to Manhattan daily and has long hours. Sometimes she's incredibly bored. "I definitely have my moments when I think, 'Oh gosh, this is what I'm doing with my life?' Especially when I spend a lot of time in the car." But on the whole, "I think I unite all my life's experience in what I'm doing right now," she says. "I can't imagine another job where I can do that."

Carole (Sonnenfeld) Geithner '83 Elise, 15; Ben, 13

Carole Geithner lucked out.

The career she loves also proved eminently flexible, letting her work a little—but never too much—once her two kids were born.

After Dartmouth Geithner decided to become a social worker and eventually earned her masters at Smith College. After working full time for two years—the only period she would work full time in her profession thus far—she stopped because she and her husband, Timothy '83, moved to Japan for his job with the U.S. Treasury Department. There they had their first child. Geithner scaled back to part time, counseling English-speaking foreigners. After returning to the United States she eventually went into private practice and declined to take clients during the popular after-school and evening hours.

She acknowledges that the boundaries limited her professional growth. But there was an upside.

"I was really thankful and happy for the time I had and the flexibility," she says. "Earning more money wouldn't compensate for the flexibility. Mainly I wanted to be there after school. So much happens then—the stories, the successes, the stresses with their teachers, with their peers." Her husband's busy travel schedule also meant she needed to be the parent there for their kids. When Tim took a job as the president of Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the family moved to Westchester County, New York, just north of New York City.

Christine (Clougher) Blel o'ch '85 Nicholas, 13; Laura, u; Danielle, 9

Christine Bielloch tried to work part time, she really did. But at a certain point this math major figured the economics just didn't make sense.

Blelloch joined an actuarial consulting firm in Boston after graduating and worked there full time for eight years until her first child was born. Then she scaled back to three days, commuting an hour to Boston from a distant suburb, where she left her son, and later her daughter, in a daycare center three days a week. If something went awry—if, for example, a child fell sick—she and her husband took turns handling it.

The arrangement worked fine until her husband, David, got a new job in his industry, construction, that allowed no flexibility for runny noses. Blelloch became the primary parent. When a third child arrived the situation proved untenable. Blelloch's part-time pay didn't outweigh the stress and the cost of daycare. "I figured it just wasn't worth it," she says.

Part of the calculus turned on the fact that even before kids, Christine didn't love her work enough to give it the kind of life commitment required to make partner at her firm. That would have required working some 3,000 hours a year.

"I was not going fast-paced to become an actuary, with or without kids," she says. "I knew I wasn't going to go the whole way at my job." She also knew she wanted to be home more with her kids. So when the time came to get behind one career as a family, her husbands was the obvious choice.

His focus on his career is paying off financially for the family. "My being home has allowed my husband to get great raises. He always says 'yes,' heworks late," Blellock says.

Although she misses Boston and colleagues, Blellock doesn't miss her job. "I love having a Dartmouth education. I love my kids knowing I have a Dartmouth education and that people think I'm smart. I like it for what it is because it makes me who I am," she says. And right now, she says, that's an at-home mom.

Paul Blackburn '88

Althea, 11; Rosalie, 6

When Paul Blackburn and his wife, Kristen Dillon '89, were first married they agreed that when they had kids childrearing would do "equal damage" to their careers. As their lives took shape, however, they took another approach: They settled into a reverse LeaveIt to Beaver lifestyle, in which Dillon, a family doctor, is the breadwinner and Blackburn is their two daughters' stay-at-home dad.

Full-time fathering is not what one might expect from Blackburn's employment history. During college summers and after graduation Blackburn worked in huts for the Appalachian Mountain Club and learned how to cook food for 100 people at a time. He transferred that know-how to soup kitchens, supervising staff that made dinner for 500 people a night. As his career developed he moved into nonprofit administration, fundraising and public relations.

Meanwhile Dillon was in medical school. When the time came for a grueling residency, the couple agreed Blackburn would take care of their I-year-old daughter. He found the stay-at-home lifestyle suited him. When the family moved to Hood River, Oregon, for Dillons practice, he continued to anchor home base.

One reason the arrangement works is that money is not an issue. "We've got lots of time in our family and not as much money. But for Hood River, we have plenty of money," he says. Moreover, they see their contributions to their lifestyle as equal.

"On the good days I say, 'Thanks for going to work,' and she says, 'Thanks for staying home,'" says Blackburn. "We both acknowledge the value of what the other person is doing. The dangers are that it can look pretty good when I'm out mowing the grass at 10 o'clock on a Tuesday and she's slogging through a difficult morning at the office." On the other side, when a child wakes up with a fever, a bike ride that had been planned is off. Then it seems it would be "kind of nice to just go to work," Blackburn says.

Robin (Hitt) Hall '86

Carly, 13; Charles, 11; Ernie, 8; Kate, 6

When Robin Hall, an environmental lawyer, had her first child, she hadn't planned to stay home. Her husband, Brad, an investment banker-turned-entrepreneur, was working long days at a new job and they had no family in the area to help take care of the baby.

Plus, law-firm life wasn't exactly family-friendly, she says. "The legal profession isn't particularly flexible in that you can say, 'I'll be there for five hours tomorrow.'"

What about her husband staying at home? That approach was not in the cards. For one, "he was a born worker; he always wanted to own his own businesses," says Hall. Also, he was making more money than she. was.

In some ways Hall was the proverbial victim of her own success. She had the education and drive to forge a career in a demanding field that didn't mesh well with parenting for her. "It's ironic," she says, "because if you shoot for a career where there is a high barrier to entry and you accomplish it, then some of what goes with it is difficult to manage with a family."

Timing is another factor. "The time when you need to be ramping up your career is also a time when women are building families," Hall says. "Those two spheres are so big at the same time."

When the Halls' fourth child was born, in December 2000, the family moved to Vermont. With the kids getting a bit older Hall started teaching power skating, coaching her son's hockey team and running a girls' hockey camp in the summer. "I didn't plan that I'd go to an Ivy League school and have four children and be a stay-at-home mom," says Hall. But her Dartmouth education "is the crux of why I am home. I am the one who teaches the kids, and they get the benefit of my experience and knowledge."

She also began doing some work again with her husband, who now owns a snack food company. That provides intellectual stimulation, as do her book club and her friends and interests, she says. As her kids get older, Hall says she expects to work more closely with her husband. With her littlest one just 6, she won't be ramping up soon. "I have another 25 years to work," she says. "The kids won't be this little forever."

Julie (Gjichouse)Mannes '86

Philip, ly, David, iz;Madison, 9;Benjamin, 10 mos.

On paper Julie Mannes has a profile that would read "work." An engineering science graduate, she started out in banking in New York, then joined an energy company in Washington, D.C. From there she enrolled at Wharton, got an M.B.A. in finance in 1992 and took a job in health-care planning. Her husband, Andrew, The 83, now an anesthesiologist, was also on the fast track to career success.

Two years after Mannes graduated from Wharton and just as she and her husband were anticipating a relocation for his career, her first child arrived. Within the next four years they had two more kids and moved twice.

There was no single conversation, no one moment when she and her husband agreed that she'd stay home full time, she says. There was a sense his scaling back would hurt his long-term career opportunities. "I never really asked him to change his career path," she says. "I was very happy being the one to do that."

Having felt the pressure of climbing the corporate ladder, Mannes considered the arrival of her first child a time "to take a little bit of a break and step back and reassess."

"I probably did things backwards, like a lot of women from Dartmouth," she says. "We went into our career choices not really thinking about what that would mean for ramifications of family life. If I had wanted to stay in the finance field and continue working full time, it really would have meant a live-in nanny or someone else taking a major role in our lives and raising the kids, and I just decided that wasn't an avenue that I wanted to pursue."

"I definitely have my moments when I think, 'OH gosh, this is what I'm doing with my life?" says mother-of-four-Ahrens. "But I think I unite all my Life's experience in what I'm doing right now"

I love having a Dartmouth education" says Blelloch. " I like it for what it is because it makes me who I am."

"It can look pretty good when I'm out mowing the grass at 10 o'clock on a Tuesday and [my wife] is slogging through a difficult morning at the office," says Blackburn.

JAMIE HELLER is an editor at The Wall Street Journal online and a mother of two. She edits the Journal's work and family blog, thejuggle.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

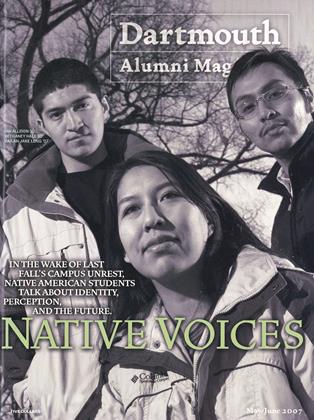

Cover StoryNative Voices

May | June 2007 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05 -

Feature

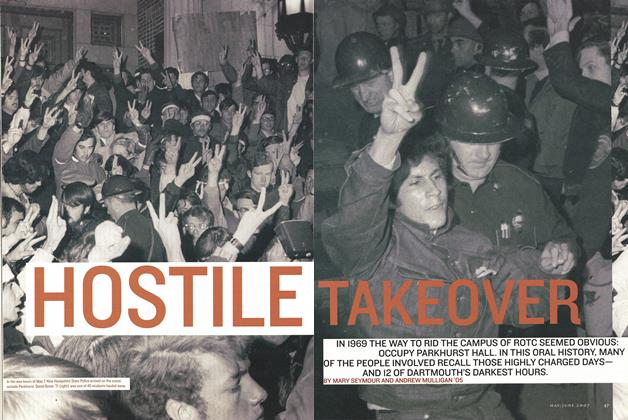

FeatureHostile Takeover

May | June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May | June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2007 By BONNIE BARBER

JAMIE HELLER ’89

Features

-

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

OCTOBER 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThorne Smith 1914

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureThe Surrogacy Option

September | October 2013 By Lisa baker ’89 -

Feature

FeatureCAN CONGRESS SURVIVE?

JANUARY 1965 By ROGER H. DAVIDSON -

Feature

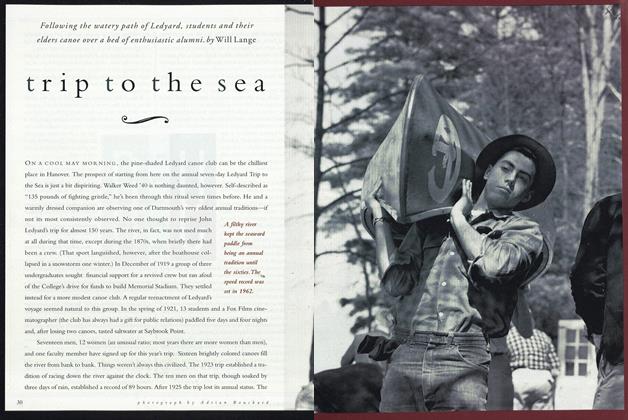

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange