A Critical Relationship

He never knew it, but legendary film critic Vincent Canby ’45 was the mentor I never met.

Mar/Apr 2001 Christopher Kelly ’96He never knew it, but legendary film critic Vincent Canby ’45 was the mentor I never met.

Mar/Apr 2001 Christopher Kelly ’96He never knew it, but legendary film critic Vincent Canby '45 was the mentor I never met.

I Never talked to Vincent Canby. Is there any reason I should have spoken with the longtime chief film critic for The New York Times, who died last October at the age of 76? Well, to take a page from the famous play (and movie) Six Degreesof Separation: In my current job, as film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, I replaced Elvis Mitchell, who was one of three replacements for Janet Maslin, who replaced Canby in 1993, when he stepped down after 24 years on the job. That's two degrees of separation. Last year, I interviewed Maurice Rapf '35, a former film critic himself and a longtime friend of Canby's, for this magazine. That's only one degree.

But there were other connections, elusive but sur-ely just as vital—those intellectual and emotional bonds we all form with complete strangers. In Canby's case: Because I started regularly reading his work in high school; because I ended up attending the same college as he did; because, as I began to find my place and voice at Dartmouth, I realized that film criticism was avocation I wanted to pursue. But, no, I never did talk to Canby.

There were times when I almost did. In college I was active with the Dartmouth Film Society, and we spoke of bringing Canby to campus. It never happened. Senior year, my friend Michael Ellenberg '97 and I considered calling him up and asking if he would let us interview him for Cahiers du Dartma, the film journal we founded. We never made the call.

And then, upon graduating, friends implored me to write or call him; ask him for one of those "informational interviews," they said. I asked other Dartmouth alumni how to break into entertainment journalism. One of them, Ty Burr '80, led me to my first job—an internship at EntertainmentWeekly. Another, Jim Meigs '80, gave me my first major break by offering me a regular freelance writing arrangement with Premiere. But for some reason I couldn't bring myself to seek out Canby.

Then, last summer, the editor of this magazine called to ask if I might try to interview Canby for a story—a conversation between two Dartmouth film critics, one in the twilight of his career, one just starting out. It sounded like a terrific idea to me—and this time, I did finally write a letter. No reply ever came. A few weeks later, I tried calling him; his voice mailbox was full. A few weeks after that I picked up The New York Times and learned that he had succumbed to a battle with cancer. I would never get to talk to Canby.

Permit me this flashback: It's a Friday morning, September 1993. I've just begun my sophomore year at Dartmouth. I buy a copy of The New York Times, and I eagerly turn to Canby's review of Robert Altman's Short Cuts—the opening night highlight of the New York Film Festival, a movie that probably won't make it to Hanover for months hence. I read his glowing review twice. The first time I ask myself: How can I see this movie? The second time I ask myself: How can I get Canby's job?

Week after week, this was my ritual. I turned to Canby to hear about the major new films that I wasn't yet able to see. But I found myself lingering upon his work. I read those reviews the way an aspiring actor might watch a Meryl Streep film, or the way a cooking student might dine at a four-star restaurant. I analyzed them, picked them apart and criticized, telling myself I could do better. I looked upon them in envy and frustration and begrudging admiration. I wondered how someone who was once a Dartmouth student landed a job so utterly cool.

In retrospect, I probably wasn't reading Canby closely enough. He got that job—and maintained it and flourished in it—because of his talent and insight and intelligence. I've spent the last few weeks sifting through The New York TimesGuide to the Best 1,000 Films Ever Made. Canby—perhaps by virtue of the modesty for which he was widely regarded by his colleagues—claimed that his reviews would never hold up in anthologized form. This is the closest thing we have to a collection of his work.

On display is his lucidity, thought-fulness and always surprising wit; despite being written under the pressure of daily newspaper deadlines, these reviews hold up just fine. Writing about The CryingGame without revealing its twist, for instance, he deftly described it as "a tale of love that couldn't be but proudly is, although even this love could be a substitute for another love that never quite was." He wrote smart, challenging reviews of films (Stanley Kubricks Barry Lyndon and Full Metal Jacket, for instance) that were unfairly dismissed or misunderstood upon their initial release. He cut to the heart of original but deeply flawed works (Apocalypse Now, One Flew Over The Cuckoo'sNest) that were perhaps too quickly embraced as masterpieces by others. His review of Gus Van Sant's male hustler drama My Own Private Idaho—a film I've written about extensively myself—offers an observation so trenchant (of the director's decision not to address AIDS, Canby wrote, "It could be that Mr. Van Sant means the film to be a fable set in its own privileged time") that it makes me angry for not having thought of it first.

Which isn't to say that if I were reviewing Canby's body of work, my praise would be unqualified. Now that I'm writing for a daily newspaper, I'm more attuned to some movie critic tricks he would too often rely upon—plot summary, for instance, as an easy way of avoiding engaging with material that you haven't quite sorted through, or describing actors as "a joy to watch" instead of explaining how and why their performances work. He also never seemed capable of embracing the low-brow pleasures of the art form—the "movies" that adamantly refused to be "cinema." Films such as Night of the Living Dead or A Nightmare on Elm Street, for instance, may be widely regarded as horror classics, but you'd never know it from Canby's casual dismissals.

And yet, the more I do my own job, the more I also admire the way Canby did his. In an interview with the Valley News in 1982, he talked about the difficulty of maintaining one's energy level as a film critic; after I recently endured a week of eight film screenings—three of which were perhaps the most tedious literary adaptations imaginable—I finally understand what he means. And becoming a film critic, in a way, has made me even more envious of Canby. He had a great job for the largest part of his professional life. I can only hope I'm so lucky.

In the end, I don't necessarily feel disappointed that I never actually spoke to him. At Dartmouth we have it hammered into our heads that we should take full advantage of the vast network of alumni connections out there for us. Would Canby have been able to offer me something—a jump-start to my career? Wisdom I couldn't glean elsewhere? Maybe. But there seems virtue, too, in sometimes keeping those alumni degrees of separation intact, in moving forward at one's own steady pace. As it turned out, I didn't need to talk to Vincent Canby. He still managed to offer me all the encouragement in the world.

A Man of His Times The critic "seldom cheers, sings or writes home," wrote Canby, whose style was described as direct and unadorned.

Christopher Kelly's movie reviews canbe read at www.star-telegram.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

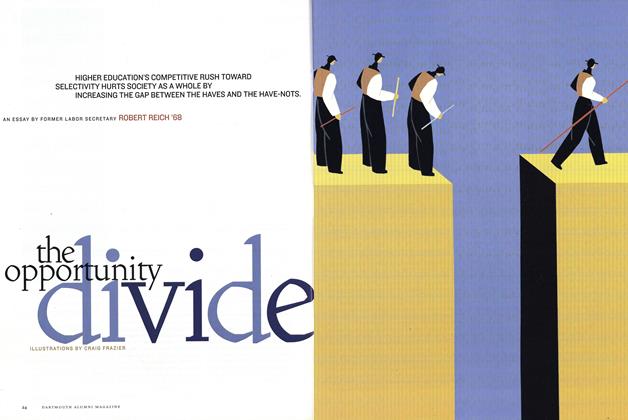

Cover StoryThe Opportunity Divide

March | April 2001 By ROBERT REICH ’68 -

Feature

FeatureRisky Business

March | April 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

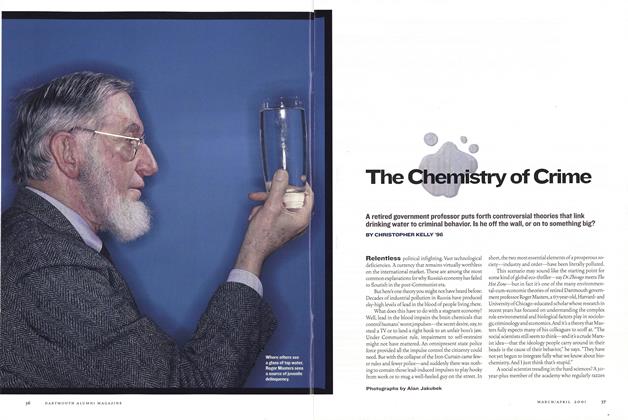

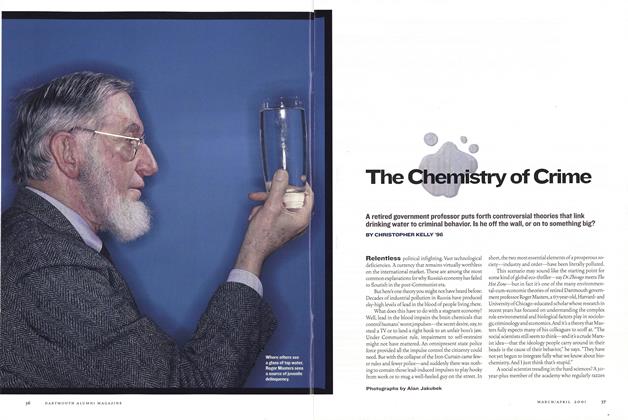

FeatureThe Chemistry of Crime

March | April 2001 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2001 -

Interview

Interview"I Was Made For This"

March | April 2001 By Henry Homeyer '68 -

Article

ArticleNorth Campus Takes Shape

March | April 2001

Christopher Kelly ’96

-

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLThe Film Society Turns 50

JANUARY 2000 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Interview

InterviewPicture Perfect

MARCH 2000 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Chemistry of Crime

Mar/Apr 2001 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Feature

FeatureBrenda and Mindy and Matt and Ben

Jan/Feb 2004 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May/June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

Nov/Dec 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPumped Up

Jan/Feb 2007 By Joel Lasky ’54 with Dan Anzel ’55 and Don Kennedy ’54 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryGreen Jacket Abroad

Mar/Apr 2004 By Laurence Sterne ’52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOne of the Boys

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By LYNN LOBBAN -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYRoyal Treatment

Sept/Oct 2009 By Richard Hansen ’07 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeasure of the Mind

Mar/Apr 2002 By Robbing Barstow ’41 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPride and Progress

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By VAL WERNER '21