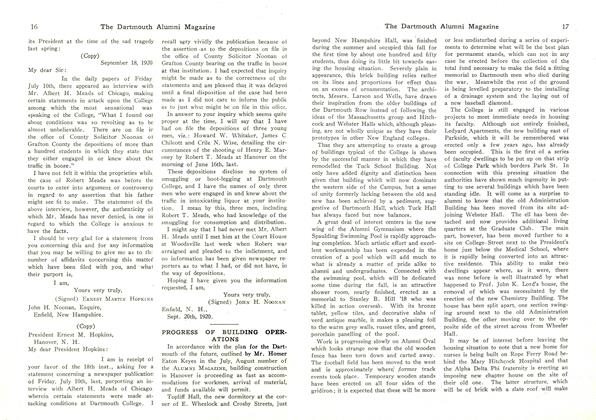

A Joyce scholar tips his hat to a demanding, charismatic mentor, English professor Peter Bien.

SEPTEMBER 1965. DARTMOUTH STUDENTS FILL Carpenter Hall for professor Peter Bien's course on the modern European novel. Physically unimposing, of medium height, balding, bespectacled, carrying a thick three-ringed notebook, he strides to the podium. In a forceful, earnest tone he says that if we read James Joyces notoriously difficult Ulysses with attention and passion, we will spend the next three weeks physically in Hanover but spiritually in Dublin, Ireland, on June 16,1904. Bien exhorts us to examine mundane experience in quest of meaning. It won't be easy. The reading list also includes The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, two volumes of Proust, Kafka, Conrad and other intricate, complex works. The professor says that because so many of the texts are despairing of human possibility, the course will begin and end with exuberantly optimistic novels, Ulysses and Zorba the Greek by Nikos Kazantzakis.

Thus began Comparative Literature 24, "Modem European Novel," for me a thrilling and utterly life-transforming course. Bien, now 76, taught the course many times between 1961, when he arrived in Hanover, and his retirement in 1997. Countless students discovered that if the unexamined life was not worth living, an examined life could be remarkably rich.

Renowned for charismatic teaching, Bien was also exceptionally demanding. "He was the most inspiring and the hardest teacher I had," recalls Jeffrey Murphy '76. "He struck terror in us the first day, announcing: 'Since the flesh is weak, quizzes will be frequent—and nasty.'" In Bien's classes there was no jollying the students with jokes or pop culture; you climbed higher summits and breathed purer air.

All the fun was in thinking, imagining, reflecting, inquiring. Michael Groden '69, a distinguished Joyce scholar, was one of many students galvanized by Bien's teaching. "I think that I have spent the rest of my life trying to give to others what Peter gave to me," he says.

The professors passionate love of language and ideas was the catalyst. Once, discussing Nietzsche's influence on Thomas Mann, Bien mused, "You know, I actually get paid for doing this!" Students would festoon campus construction fences with Comp Lit 24 graffiti, mantras and tag lines from Ulysses.

My first visit to Terpni, the Biens' farm in upstate New York, was in July 1969, when I was a graduate student in need of the mentoring I had been given at Dartmouth. I found Bien tinkering with an ancient tractor. "It's 35 years old," he said, energetically turning the crank, "and sometimes it's obstinate." Eventually, to his gratification, the engine sputtered and started.

I was astonished to discover that Bien, my model of spiritual, intellectual and aesthetic pursuit, was also a farmer, builder and mechanic. As a 20-year-old undergraduate at Harvard he had purchased 120 acres for $1,200, cleared the land and constructed a log cabin with trees that he felled, skidded with a horse, peeled and dried on the farm. When he married, he and his bride, Chrysanthi expanded the house for their three children. (He now summers there, spending the rest of his time in Hanover.) "Terpni" is the name of the village in Macedonia where Chrysanthi was born, and in ancient Greek, Bexplains, the word has "a very nice meaning: enjoyable.'"

Finding and giving joy always animated Bien's teaching; he was bearingwitness as a professor, and his texts were humanist gospel. What do Ulysses or The MagicMountain or Zorba the Greek want us to believe and feel? Bien testified to the power of literature, "the human activity," in Lionel Trilling's words, "that takes the fullest and most precise account of variousness, possibility, complexity and difficulty."

One perennial source of Bien's gusto and commitment is his spirituality, especially the Quaker ideal of nonviolence. When we students conducted peaceful protests against the Vietnam War he joined us in vigils; it was another form of bearing witness. In class Bien stressed that Joyces Leopold Bloom is a man of pacifist sympathies, humane instincts, uncommon decency. Bien celebrated what he called Blooms "pure ability to exist sensually and his strong will to live fully."

Bien's perspective as a lecturer was both micro and macro, moving from minute details to the overall vision of the work. "Joyces novel approaches poetry," he said. "As a 'rule of thumb, absolutely nothing in Joyce is accidental. Everything in Joyce is done in two modes," often con- tradictory ones or opposites. "We can only know the spiritual by comprehending the material; to know God we must immerse ourselves in a world of flux." One is, or might be, capable of sudden intuitive glimpses through ordinary expereince. A Joycean "epiphany," according to Bien, is a "showing forth of essential meaning of some object or event or sensual experience; it comes in a flash, where- in the object becomes radiant."

Joyce, Bien emphasized, is "one of the sanest, least pathological of writers. The flesh is also God's work, and human foibles are treated as comic, not sick. Joyce finds life stimulating, exhilarating—and positive." In the end, Bien said, "Reason triumphs—not in the old heroic manner, but in a victorious fashion. The optimism of Joyce is analogous to the optimism of Christianity, in a modern, non-dogmatic spirit." Joyce, Bien said, demonstrates the "the ability to stand off from one's own grief and to see the humor."

A course with Bien was a complete liberal arts education in miniature. Drawing deeply from philosophy, the arts, relighion, psychology, political science and history to illuminate Woolf, Kafka, Conrad and Proust, Bien linked 20th- century novelists to Freud or Nietzsche, Wagner or World War I. Especially dear to Bien are the Greek connections. Bien, who married a Greek woman of beauty, vitality and warmth, often visits Greece. He loves Homer and has written three textbooks on Modern Greek; he is the world's foremost expert on Zorba author Kazantzakis. In addition to literary critical and biographical studies of the 20th-century writer, Bien has translated The Last Temptation of Christ and Reportto Greco.

Returning last summer to Terpni, I found him essentially unchanged: physically active, enjoying life lustily, over- flowing with projects and perceptions. In "retirement" he seems busier, if possible, than ever. The pillars of his life remain solid—visiting professorships at Columbia, Princeton, Brown and the University of Crete; his wife and family; schol- arship; his Quaker mission; and work at the farm.

Bien's library is crammed floor to ceil- ing with books. He writes and conducts his research under a large yellow birch tree in a three-sided Adirondack lean-to facing south, where he is so quiet that deer often graze undisturbed in front of him. The second, concluding volume of his critical and biographical study, Kazantzakis:Politics of the Spirit, was published in January by Princeton University Press, and his massive, annotated Kazantzakis correspondence Nears completion.

As an emeritus professor about the only thing Bien no longer does is hold important administrative positions. At Dartmouth he served on the faculty- elected committee advisory to the president and the committee on organization and policy, chaired the comp lit program, co-directed the War/Peace Studies Program, and founded the composition center and the Center for the Humanities university seminars program. Freed from such administrative responsibilities, Bien has developed a new passion—the music of Johnny Cash. "What a voice!" says Bien. As Chrysanthi says, "I've been with him 50 years and I still don't knowwhat's in his head. His head must be very split; he has so many branches."

Bien indeed is many-minded. Correspondence with his former students produces a consistent portrait. Murphy, now a lawyer in New York, says that he has never encountered anyone "who was able to balance genius, achievement and hu- manity as does Professor Bien. I only hope that my children encounter such a teacher." Biens teaching, writes Groden, opened "many different worlds to me: Ulysses and all its wonders; literature and ways of thinking and talking about it that matter to us in our lives; the university professor who lives immersed in literature and dedicates a life to thinking, talking and writing about books."

Bien taught us that "victory is contingent, but we squeak through. We survive. Joyce depicts 20th-century man not as noble but heroic, limited but, barely, triumphant. What we learn from this course," Bien concluded in 1965, is that "civilization has given a splendid way to answer life: ait." No wonder so many of Biens students shared what he characterized as "a sense of awe before such miracles."

In his life and work Bien embodies the optimism and faith, discipline and commitment, magnanimity and agape (Greek for love) that touched and stimulated countless students, colleagues and friends. His translation of Cavafy's poem "Ithaca" offers a prayer that is also, I believe, Biens conviction:

Pray the route be long. That on many a summer morning (with what delight with what joy!) you enter harbors you have never glimpsed before... Always keep Ithaca in mind. Arrival there is your destined end. But do not hasten the journey in the least. Better it continue many years and you anchor at the isle an old man, rich with all you gained along the way...

Joy of Joyce The Irishauthor demonstrated the"ability to assuage thetragic in life with humor,"says Bien, now retired.

A course with Bien was a complete liberal arts education in miniature.

ROBERT H. BELL is the William R. KenanProfessor of English at Williams College andauthor of Jocoserious Joyce: The Fate of Folly in Ulysses. In 2004 he was namedthe Carnegie Foundation/CASE Professor of the Year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

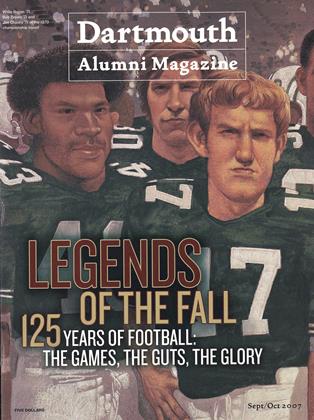

SPORTS

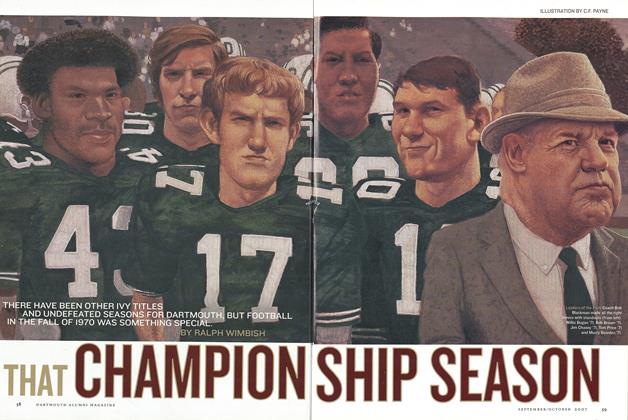

SPORTSThat Championship Season

September | October 2007 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

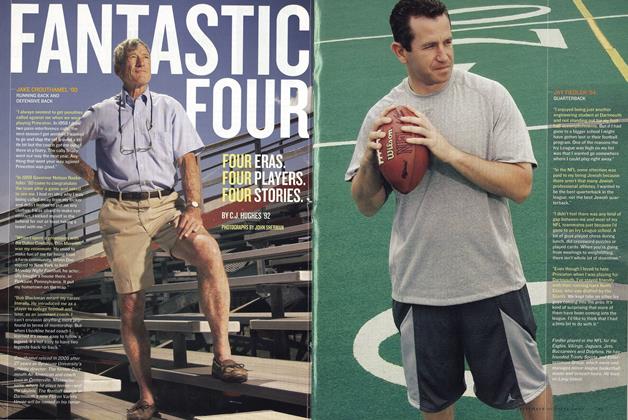

FeatureFantastic Four

September | October 2007 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

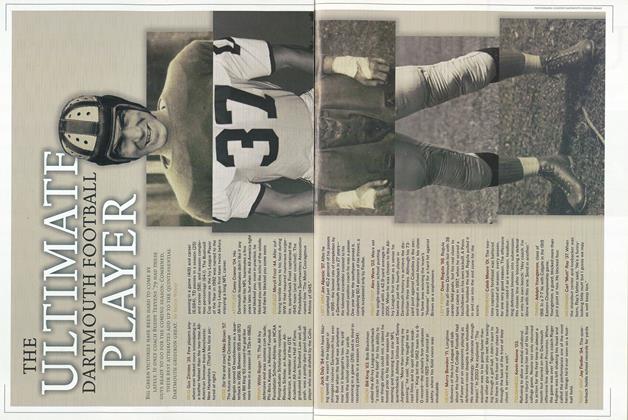

FeatureThe Ultimate Dartmouth Football Player

September | October 2007 By Bruce Wood -

Feature

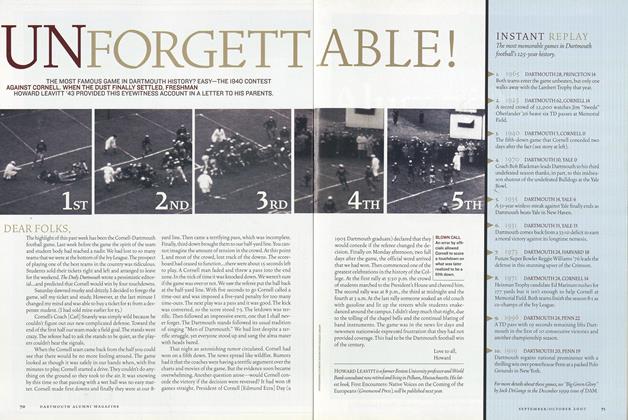

FeatureUnforgettable!

September | October 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

SPORTS

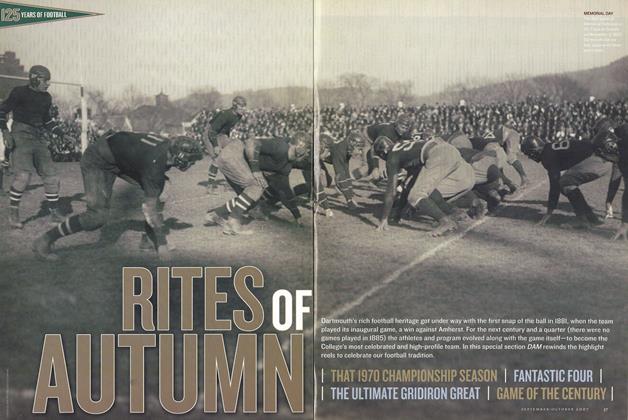

SPORTSRITES OF AUTUMN

September | October 2007 By Courtesy Dartmouth College Library -

Feature

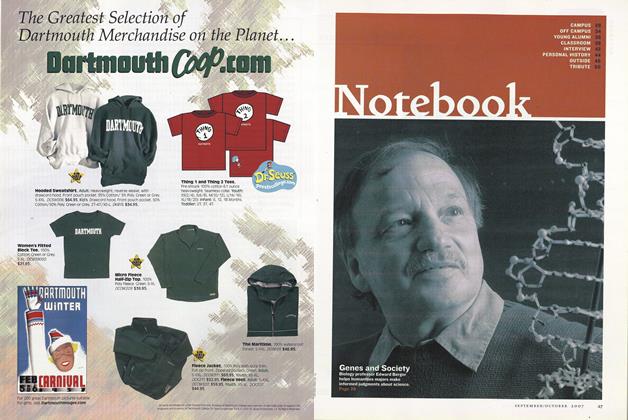

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74