An anonymous benefactor leads a grateful alum to make the promise of a lifetime—and provide a lasting return on the investment.

I AM NOT ONE FOR REMEMBERING DETAILS. I RECENTLY BROWSED through an old 3.5-inch floppy disk that holds papers I wrote at Dartmouth for my more advanced economics classes and marveled that I could not remember even writing some of them. Yet I remember in perfect detail the day during my sophomore spring when I received a letter from the financial aid office. I had picked up my mail from my Hinman box and was crossing the Green back to my triple in Hitchcock. I opened an official-looing letter that stated my financial aid grant was now to come from an endowed fellowship. I had not applied for this fellowship. According to the letter, I had been selected for my academic interests and involvement with the rowing team. The only requirement of the fellowship was to write a letter at the end of each spring to its funder (whom I'll refer to as "Sam" in keeping with his insistence upon anonymity).

I came to Dartmouth from a working class family where the most money anyone ever handed me was a $30 check from an aunt for Christmas or the $20 bill my grandmother crumpled into my hand when I visited. During my 13 school years in the New York City public school system I was never given anything I did not have to return—from my mathematics textbook to my ratty basketball uniform. I initially received a Dartmouth financial aid grant because my single mother did not earn a lot of money; I received the endowed fellowship because of who I was. Dollar for dollar, I was to receive the same amount of aid through this endowed fellowship as I had from the Dartmouth financial aid grant, but it felt different. I felt different. I felt recognized. I felt confident I had succeeded at Dartmouth and that I could continue to be successful.

Each spring, before I left campus, I drafted a letter to my generous benefactor. During the three years I detailed a part of my Dartmouth journey. I chronicled my apprehension at giving up my plans to major in mathematics, then my fear of not knowing what to do instead, of finding comfort in the economics and, later, education departments, and of considering and then abandoning apremed track. I always wrote about my life on the rowing team, because that was the cornerstone of my Dartmouth experience from my struggles as the third varsity coxswain my sophomore year to my uneasiness at stepping up to first varsity coxswain my junioryear to my love of being in that position my senior year. I also touched on my involvement in the social scene and the comfort I felt in the space Sigma Delt provided. In my letters I mentioned a few personal struggles, such as having to undergo emergency surgery to remove a melanoma at the start of my junior year, which left me back on campus with no time to process what had happened before I was thrown into "Financial Intermediaries and Markets" and the fall crew season. At the end of each letter I expressed my gratitude, provided my contact information and signed my name.

Except for the large lump sum that was indicated on my financial aid letter each year, I never heard from my benefactor until the summer after I graduated, when my mother received a message from Sam on her answering machine. Without hesitation I called him back. I do not remember the details of that phone call, but in the end we exchanged e-mail addresses and began a haphazard correspondence when we felt the motivation to write.

When I sought donors for an AIDS ride from Boston to New York, which I took part in with my mother in 2001, I included Sam on my mailing list. He promptly replied with a generous donation and told me that his cousin—whom he had honored with the endowment I had received—was a gay man who had died of AIDS. I had been selected for this endowment while at Dartmouth because I matched a set of academic and extracurricular criteria, but in the end I felt a sense of connection to the man the gift honored, both in my actions and my being. I had realized my own sexuality at Dartmouth.

My benefactor expressed not only delight in donating to the AIDS ride but also interest in continuing to assist me financially if I returned to school. His caveats were that I could not broadcast his generosity and that if I were ever in a position to help someone else later in life, I would do so. He kept to his word both when I returned to get my M.A. at Columbia University's Teachers College in 2003 and last year, when I began working toward a Ph.D. in international education development at New York University. Although we have met in person only once, we continue to exchange detailed e-mails that I greatly look forward to. Sam's e-mails often humbly detail his present influence on someone else's life and my e-mails allow me a space to reflect on my progress since Dartmouth, which I do not do frequently enough.

While Sam's financial donations to my undergraduate and graduate degrees have eased the financial pressures a bit, his emotional investment, as expressed through his honest and candid words to me, mean even more. At first it was hard for me to comprehend how this man could hand over so much money to Dartmouth without even knowing who I was, then help me with my graduate education without requiring that I pay him back. But through his words I've come to realize that he invested his money in me knowing he will get a return on his investment. This may not come in the form of cash but will happen through my personal development and my helping others unconditionally in my own life.

Sam never tried to steer my path, but rather encouraged me and praised my choices. His circumstances allowed him to support me financially, and his decision to use his money in this way showed me we can all choose to invest in others in our own unique way. I am uncertain as to when I will be in a position to pay forward my promise to Sam of helping others further their educations through a financial mechanism; however, expanding access and quality education—especially to those in greatest need—serves as a foundation of my current and future study and work.

ATHENA MAIKISH is a Ph.D. student atNew York University studying the economics, financingand reform K-12 education in Africa.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

SPORTS

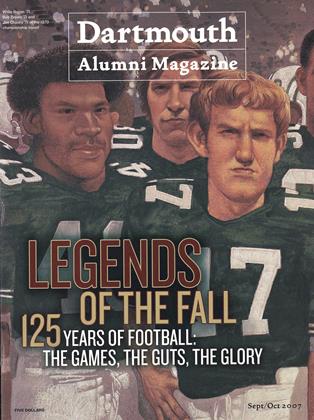

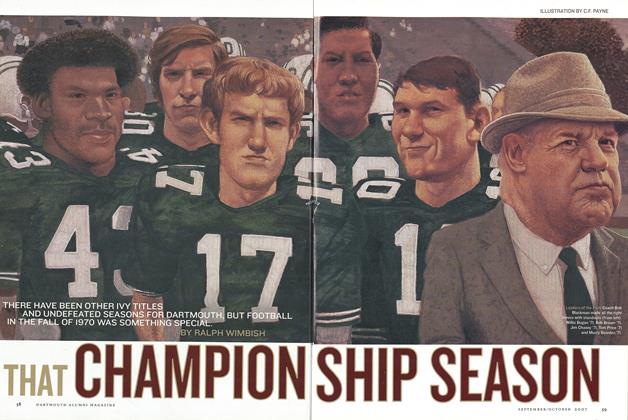

SPORTSThat Championship Season

September | October 2007 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

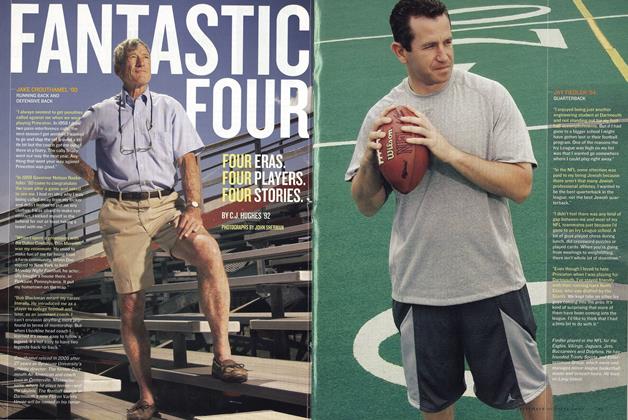

FeatureFantastic Four

September | October 2007 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

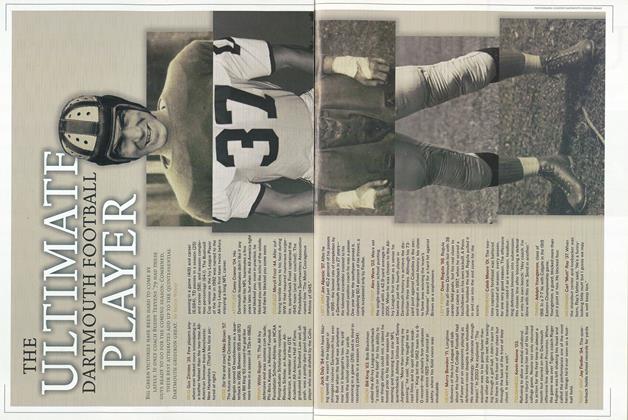

FeatureThe Ultimate Dartmouth Football Player

September | October 2007 By Bruce Wood -

Feature

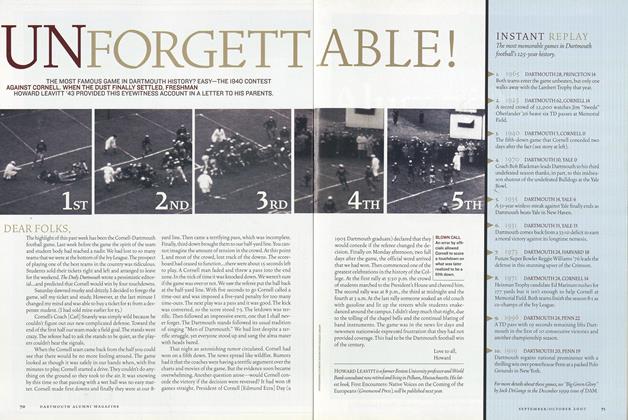

FeatureUnforgettable!

September | October 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

SPORTS

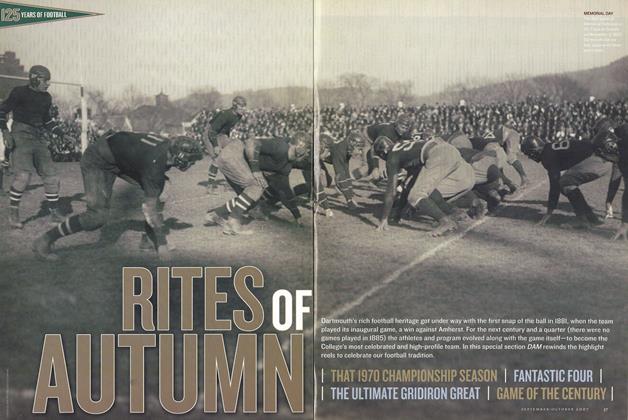

SPORTSRITES OF AUTUMN

September | October 2007 By Courtesy Dartmouth College Library -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74