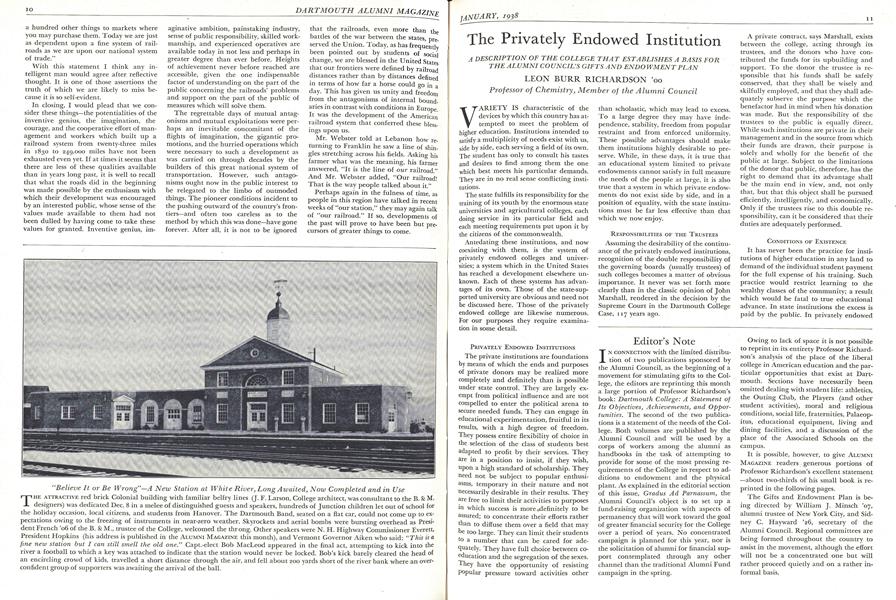

A DESCRIPTION OF THE COLLEGE THAT ESTABLISHES A BASIS FORTHE ALUMNI COUNCIL'S GIFTS AND ENDOWMENT PLAN

VARIETY IS characteristic of the devices by which this country has attempted to meet the problem of higher education. Institutions intended to satisfy a multiplicity of needs exist with us, side by side, each serving a field of its own. The student has only to consult his tastes and desires to find among them the one which best meets his particular demands. They are in no real sense conflicting institutions.

The state fulfills its responsibility for the training of its youth by the enormous state universities and agricultural colleges, each doing service in its particular field and each meeting requirements put upon it by the citizens of the commonwealth.

Antedating these institutions, and now coexisting with them, is the system of privately endowed colleges and universities; a system which in the United States has reached a development elsewhere unknown. Each of these systems has advantages of its own. Those of the state-supported university are obvious and need not be discussed here. Those of the privately endowed college are likewise numerous. For our purposes they require examination in some detail.

PRIVATELY ENDOWED INSTITUTIONS

The private institutions are foundations by means of which the ends and purposes of private donors may be realized more completely and definitely than is possible under state control. They are largely exempt from political influence and are not compelled to enter the political arena to secure needed funds. They can engage in educational experimentation, fruitful in its results, with a high degree of freedom. They possess entire flexibility of choice in the selection of the class of students best adapted to profit by their services. They are in a position to insist, if they wish, upon a high standard of scholarship. They need not be subject to popular enthusiasms, temporary in their nature and not necessarily desirable in their results. They are free to limit their activities to purposes in which success is more to be assured; to concentrate their efforts rather than to diffuse them over a field that may be too large. They can limit their students to a number that can be cared for adequately. They have full choice between coeducation and the segregation of the sexes. They have the opportunity of resisting popular pressure toward activities other than scholastic, which may lead to excess. To a large degree they may have independence, stability, freedom from popular restraint and from enforced uniformity. These possible advantages should make them institutions highly desirable to preserve. While, in these days, it is true that an educational system limited to private endowments cannot satisfy in full measure the needs of the people at large, it is also true that a system in which private endowments do not exist side by side, and in a position of equality, with the state institutions must be far less effective than that which we now enjoy.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE TRUSTEES

Assuming the desirability of the continuance of the privately endowed institutions, recognition of the double responsibility of the governing boards (usually trustees) of such colleges becomes a matter of obvious importance. It never was set forth more clearly than in the classic opinion of John Marshall, rendered in the decision by the Supreme Court in the Dartmouth College Case, 117 years ago.

A private contract, says Marshall, exists between the college, acting through its trustees, and the donors who have contributed the funds for its upbuilding and support. To the donor the trustee is responsible that his funds shall be safely conserved, that they shall be wisely and skilfully employed, and that they shall adequately subserve the purpose which the benefactor had in mind when his donation was made. But the responsibility of the trustees to the public is equally direct. While such institutions are private in their management and in the source from which their funds are drawn, their purpose is solely and wholly for the benefit of the public at large. Subject to the limitations of the donor that public, therefore, has the right to demand that its advantage shall be the main end in view, and, not only that, but that this object shall be pursued efficiently, intelligently, and economically. Only if the trustees rise to this double responsibility, can it be considered that their duties are adequately performed.

CONDITIONS OF EXISTENCE

It has never been the practice for institutions of higher education in any land to demand of the individual student payment for the full expense of his training. Such practice would restrict learning to the wealthy classes of the community; a result which would be fatal to true educational advance. In state institutions the excess is paid by the public. In privately endowed colleges it becomes a charge upon those embers of the community, fortunately situated in respect to personal means, who consider the endowment of charitable and educational enterprises as the natural and roper use of their surplus funds. Such donations have been and must continue to be the sole resource of the privately endowed college for its very existence. The generosity to its charitable institutions of men and women of means in the United States has long been the admiration of the rest of the world. The colleges of the country have had their full share of these benefactions. But at the present time a crisis is before them. Economic and social conditions have changed. It is no longer so easy for men to amass money as it once was: under modern systems of taxation it is no longer possible for men to regard possessions once amassed as really under their unlimited control as once they were. Under these circumstances a problem is presented to the public spirited and generous man of wealth as to the means which he shall adopt to fit his response to worthy public causes to these new conditions. Equally difficult is the problem presented to the colleges: How under the new dispensation shall the necessary increases of endowment, plant, and equipment be se- cured?

To make the solution of this problem more pressing it must be remembered that the one condition impossible of realization in our private institutions is that of rest: either they must go forward or go back. In them the minimum requirements of each succeeding period inevitably demand added means, if the college is not definitely to lose ground. As an illustration, consider the strenuous and fairly successful attempt made fifty years ago in Dartmouth College to secure permanent support for a professorship in each of the important subjects then taught. Thirty thousand dollars was deemed sufficient for each of these endowments. Today the income of such a sum hardly serves to support the teacher of lowest grade in the faculty group. Then the number of teachers in each of the endowed departments was one. Now it has risen to numbers varying from five to forty. Then the departments endowed were supposed to be all that were required in a college of the highest grade. Now three times as many departments are needed as were thought to suffice in the olden day. An institution today depending upon the means which, perhaps, were adequate in 1885 could offer but the poorest apology for an education. If a college is to live, it must advance.

It is also to be remembered that periods of business prosperity are not necessarily periods of prosperity for the college. Expenses increase all out of proportion to fixed income, and, unless a stream of donations is available by which that income is increased, times of general prosperity are likely to be times of adversity to the college.

However true these considerations may be, it is obvious that even in these days the privately endowed college, as in the past, must place its reliance upon the benefactions of private donors. It is evident that such donors cannot, from the nature of things, have at their disposal the available resources which were at their command in former years. It follows that more than ever it is necessary for them to obtain full assurance that their benefactions shall be worthily bestowed. They have not only the right but the duty to ask how well the trustees are meeting the demands, private and public, outlined in the section above. They must convince themselves that the institution, in its educational program, is meeting the needs of the day; that it is alert, intelligent, and resourceful; that its standing among other institutions of its type is high; that its funds are administered prudently and effectively; that it has well-formed and definite reasons for all its activities and jalans for their successful accomplishment —in short, that the institution gives to the public full value for the money intrusted by private donors to its hands. To give information concerning these points, which may lead to valid conclusions so far as Dartmouth College is concerned, is the purpose of the following pages.

HISTORY OF THE COLLEGE

Dartmouth College is the immediate outgrowth of Moor's Indian Charity School established in 1755 by the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock for the education of the Indians at Lebanon (now Columbia), Connecticut. In 1766-1768 this school received an endowment of some £10,000 from England through the personal solicitation in that country of the Reverend Samson Occom, an Indian missionary; the largest sum of money received by a colonial educational institution from the motherland in pre-revolutionary days. Upon the basis of this endowment Wheelock removed his school to the "wilderness," in Hanover in the Province of New Hampshire in 1770. Coincident with the removal Wheelock added to his educational enterprise a college for whites, a royal charter for which was granted by Governor John Wentworth of New Hampshire in 1769. The College was the eighth institution of similar rank to be founded in the English colonies in America. It was named for Wheelock's English patron, the second Earl of Dartmouth. In the course of time the Indian school became superfluous and disappeared, but the College persisted. Its first class, numbering four members, dates from 1771. Since that time no year has passed without a graduating class, a condition (due to the isolated position of Hanover, and of the effect of the war of the Revolution upon its seven sister institutions) true of no other college of America.

Down to 1892 the College was a small institution, with an average attendance of some 300 men students. Its growth then became rapid, but stability of numbers was reached by a decision of the trustees in 1919, which limited enrollment to 2000. Later it was allowed to increase to 2400; at this point it has been fixed for some years. During its history it has graduated some 17,000 men, of whom some 11,000 are still alive. It has had its share of men of eminence among its sons; and, a contribution perhaps equally important, it has sent out multitudes of graduates who, without attaining widespread fame or reputation, have been highly useful, respected, and influential citizens in the communities in which they have passed their lives. So far as an educational institution could accomplish that result, it has contributed toward the qualities which have marked men of both these classes. The College has always had an unquestioned reputation as an institution of high effectiveness among the older American institutions.

A LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGE

For many years the trustees of Dartmouth have had, and they still retain, definite ideas of the limits within which the institution should work. "Keeping up with the Joneses" is as common among institutions as it is among men, but it is a tendency which the governing board has been wise enough to avoid. Certain definite guiding principles have animated its action. It has refused to allow the College to undertake types of educational effort to which Hanover, in its geographical isolation, is not we" adapted. It has refused to initiate or to carry on work of graduate or professional grade, adequately and competently provided for elsewhere, which, if done, would result in needless duplication. It has never assumed new and untried functions merely to promote institutional prestige. It has never strained college finance to attain extension of its field at the expense of quality of the work done. It has refused special endowments which would take the institution beyond its chosen range. It has long been and continues to be the guiding principle of the Board to do those things only which equipment, resources, and natural conditions permit the College to do as well or better than any other institution can do them.

As a result, for the most part Dartmouth has been and will continue to be a college of liberal arts, with no aspirations or ambitions to the status of a university. Such allied schools as exist in conjunction with its undergraduate activities are few in number; they have developed logically and naturally from the existing situation; they limit their work to what they can do with high effectiveness, and make no pretensions to extension beyond reasonable limits. Their status will be explained in the discussion which is to follow. It may be admitted that this restriction of the activities of the institution mainly to undergraduate instruction involves certain handicaps. Nevertheless, in the minds of the trustees and of all others who are interested in the institution, the advantages of this limitation are so predominating as to make it a policy concerning which no diversity of opinion exists.

THE TRUSTEES

According to the charter of 1769 the governing board of the College is made up of twelve trustees. Two of them hold their positions ex officio; the President of the College and the Governor of New Hampshire. The remainder were originally elected by the Board itself, for life. That arrangement still prevails in theory, but in practice five of the trustees are nominated by the alumni; a nomination always ratified by the Board. This class of trustees, by a self-denying ordinance, upon election Slgn a resignation dated five years ahead, so they really serve for that period only, although eligible for re-election for a second, but not for a further term. The other five trustees, elected by the Board, have unlimited tenure.

Theoretically, again, in accordance with the terms of the charter, the trustees are complete dictators of the College, with no limitation upon their power. Practically, a division of responsibility exists, in which each branch of the College organization assumes those responsibilities which it is best fitted to fulfill.

THE FACULTY

The officers of administration and instruction of the College (and the Associated Schools) number about 300. Subject to the trustees, the faculty is responsible for the educational policy of the institution, for its curriculum and for its academic administration. The President of the College is a member of both bodies, and serves as a connecting link between them. The teaching body is a cosmopolitan group, with backgrounds derived from attendance at a wide variety of undergraduate and graduate institutions.

In accordance with the demands of the liberal college, the indispensable requirement of the teacher at Dartmouth is thorough and comprehensive understanding of his chosen subject and proven ability to impart it to others. Knowledge of details, coupled with a proper comprehension of relationships; interest in and enthusiasm for the subject itself; experience and success in the art of instruction and strong liking for it: these are the imperative requirements of the Dartmouth teacher. Enthusiasm for research, which is normally coupled with these qualities, is encouraged, and ample opportunity is given for work of this character. Such library and other facilities as are normally required for research are quite adequate, although the research worker does not have at his disposal large numbers of unpaid helpers, by whom his ideas may be developed and tested, such as are supplied by the graduate students in universities maintaining large graduate departments.

STUDENTS: NUMBERS AND ADMISSION

The size of the College and Associated Schools is now fixed by the trustees at about 2400. This figure was arrived at as a result of careful consideration of the resources of the institution, and of the material conditions which prevail at Hanover. It is large enough to warrant reasonable scope and diversity of subject matter, and variety both of character and personnel of instruction. It is a number capable of being accommodated without unduly straining the material facilities of the institution. On the other hand, it is not so large as to be unwieldly or to lack homogeneity. It seems a satisfactory compromise between the very large and the very small college.

For many years it has been the theory at Dartmouth that transition from the secondary school to college should be easy and natural. It has not seemed to the trustees that in all respects the system of admission by examination answers this requirement. Under it, the attention of the school, in the later years of the student's preparatory course, at least, must be centered, not upon his normal and natural educational advance, but largely upon preparing to meet a specific test. The matter of supreme importance in his mind, likewise, is sure to be facility in passing the examination rather than real and adequate preparation for the work of the College. The examination is made a goal, rather than an incident. Moreover, it is by no means certain that such tests constitute an unfailing indication of scholastic competence. Skilled tutors, with uncanny ability to forecast questions likely to be on the paper, together with intensive cramming by the student, are not uncommon and they can accomplish wonders in enabling the candidate to meet such tests, while, in his subsequent college career, the results do not always indicate that the test told the story that it was intended to tell.

A more reasonable system seems to be one in which reliance is placed upon the evidence of those who know the student best and are fully informed as to his competence to do college work, provided, of course, that such men can be relied upon to tell the truth. The experience at Dartmouth has shown that, in the vast majority of cases, the evidence of secondary school teachers is to be trusted. Accordingly for many years the College has operated upon the certificate system of admission (except in cases in which the evidence is uncertain or lacking), with results that are satisfactory.

After the World War, when applications for admission to Dartmouth, as to other colleges, increased far beyond the capacity of the institution, a serious problem arose. How should an effective selection be made from the multitude of those applying for admission? The trustees set themselves earnestly to the solution of this problem. Two questions were involved: first, what kind of boys does Dartmouth wish to train? and, second, how shall boys having these particular qualities be detected? The result of the deliberations of the governing board was the Selective Process, initiated with the class admitted in 1922. It was the first system of its kind to be installed in an American college, and was greeted by other institutions, at its inception, with a certain measure of doubt, not unmixed with suspicion as to its motives. The best indication of its success is that many of its elements have been adopted by other colleges, although not always with complete frankness.

The system, administered by a director of admissions, works as follows. The original list of applicants is made up of candidates who present from approved schools full scholastic credentials for admission without condition. No other candidates are considered. (All of these men have been admitted without question in earlier years.) This list generally numbers two or three times as many as can possibly be received.

However, the school certificate is only the beginning of the matter. Further information is obtained by letters from the boy himself, from his school principal, from persons in the community who know him well. Added to this is a personal interview with the boy by an alumnus or a committee of Dartmouth alumni, especially selected in each locality to do the work. Their rating of the candidate is made a part of his record. In all this investigation the purpose is to secure information, not only as to the scholastic ability of the student, but as to his other qualities; his tastes, his interests, his personality: in other words to find out in as much detail as possible what kind of a boy he is. The accumulation of evidence concerning each candidate is wide, full, and generally reliable.

With this information at his disposal, the director of admissions sets himself to select the class. First, the group of men of whom all show high scholastic records and definite promise of intellectual superiority is separated from this mass. These men constitute the first preferential group and are admitted without further question. After them come men to whom preference is given on account of geographical location. Candidates from the state of New Hampshire are placed ahead of those coming from other localities, on account of certain historic relations between the College and the State. Candidates from regions west of the Mississippi and south of the Potomac constitute another preferred class. It has for some years been the theory of the trustees that a cosmopolitan student body is of advantage. Sons of alumni of the College are also given a preferred position. Remaining are a large number of men whose scholastic records are satisfactory, but not outstanding, and all of whom so far as this qualification is concerned, are so much on a parity as to give no real opportunity for choice. Here the other characteristics of the candidate are carefully examined. What outstanding qualities does the man possess in other than scholastic lines? In preparatory school has he engaged in athletics? Is he interested in music, in school journalism, in dramatics, in other school activities? Does he have worth while hobbies? Has he shown traits of leadership? Has he any interests which set him off from his fellows? The man who can show outstanding qualities such as these in almost any line of endeavor is chosen in preference to the man who seems to possess none of them. By the selection of a certain number of the best of these men the class roll is completed.

By this method an annual selection of from 600 to 700 men (depending on the number retained in the upper classes) is made from a list of well-qualified applicants which ranges from 1800 to 2500. One purpose attained by the plan is to secure an undergraduate body in which a proper standard of competence shall prevail, uninfluenced by the economic status of the entering student. Dartmouth has always been a democratic institution, and it is the intention of the trustees that such democracy shall continue. The student body is made up of rich and poor alike, and there is no discrimination among them either in the minds of those administering the College or in the minds of their fellows. The method also eliminates those who are not qualified either by mental capacity or by failure of purpose to do college work—a principle the beneficial effect of which is most striking toward those men themselves. The complaint sometimes urged that too many boys go to college has very little application to the freshmen who annually enter Dartmouth.

A MORE EFFECTIVE METHOD

While no one claims the system to be perfect, it has effected a surprising improvement over former conditions. The number of candidates admitted who show themselves unable or unwilling to do college work now is but a small fraction of those who years ago had to be numbered in that category. Separations because of academic deficiencies during freshman year constitute now a surprisingly small percentage of the class. The cooperation of secondary school authorities in telling the whole truth about their graduates has been excellent. The alumni committees, as soon as they learn by experience what their work and their responsibilities really are, furnish information which is nearly always accurate and reliable. The number of candidates in the higher scholastic levels is steadily increasing. In the mind of no one who has watched the undergraduate body for a number of years is there any doubt that the system has succeeded in bringing to the College, not only more men of a high order of scholarship than was formerly the case, but also in general men of personal attractiveness, manliness, willingness to accept responsibility, and other characteristics which make for success in the work of the world.

From a geographical point of view, the success of the system is also unquestioned. Perhaps Dartmouth is now the most cosmopolitan of American colleges. In the year 1936-1937, 45 states, as well as 12 foreign countries, were represented in its student roll of 2460 men. Massachusetts leads with 538, but New York follows closely with 535. Then come New Jersey (256), Connecticut (177), New Hampshire (162), Illinois (145), and Pennsylvania (102). From territory west of the Mississippi come 149, of whom 47 are from the Pacific coast. The students from the South number 35. In all 60% of the student body have as their homes the region outside the six New England states.

The institution, furthermore, has adopted the novel principle that its one and only reasonable demand, so far as the entering student is concerned, is that, by training and natural ability, he shall be prepared adequately to do work of college grade. The College is, therefore, somewhat skeptical of the validity of the idea, generally held, that such capacity is best measured by the accumulation of preparatory school credits and units in narrowly specified subjects, the summation of which is supposed to be a certificate of competence. In the main, Dartmouth has abandoned that idea. For the superior student such limitations are almost entirely disregarded; for the ordinary one, very largely so, although work adequate in quantity and superior in quality is, of course, insisted upon in all cases. Under this new concept, the boy in the preparatory school is more at liberty to pursue a course adapted to his particular needs, and the preparatory school itself secures a larger degree of freedom in the direction of its students: always with the limitation, however, that, whatever course is adopted, the man whom it recommends must be prepared to do college work, and must be fitted, both extensively and intensively to do it well.. This relaxation of red tape has been welcomed by most preparatory schools as affording them a degree of freedom, which they have a right to expect, coupled with, increased responsibility, for results, which, they are willing to assume. The outcome shows that a more adequately prepared, student body comes to the College than was the case under the former rigid system of narrowly limited units of credit toward admission.

THE CURRICULUM

The one fundamental purpose of the College is the intellectual development of the student. Without that it has no excuse for being. In the last analysis that development depends upon the student himself. Given the opportunity, with proper capacity, wisdom, purpose, and effort, he can make almost any desired advance, if he really wishes to do so. Curricular requirements, restrictions, limitations, prescriptions are not of predominating importance if he really wishes to learn. Nevertheless,, they have their significance. Carried to extremes they often stand in the way of the earnest man who knows exactly what he wants and is determined to attain it. To him they are irritating and seemingly purposeless obstacles. But for the College at large they cannot be eliminated. In their absence the man of indolent and thoughtless temperament, inclined to take the easiest way, is given the opportunity to doze through college on a flowery bed of ease,. with advantage neither to himself nor to those with whom he associates.

Two opposing theories of curriculum building have been in vogue. The first, which was universal in our colleges until times comparatively recent, is the system of rigid prescription. It is based on the principle that wise men with broad outlook and keen vision should carefully and thoughtfully evolve the best and most effective combination of subject matter to lead to the desired educational end. That program once drawn up, the student was expected to follow it without question or objection. Practically, however, curriculum building of this type was not usually carried out in exactly this manner. The normal course was for each department in the College to seize as much of the student's time as it could induce the rest of the faculty, after much quarreling, to grant, and the program which resulted was usually a compromise which passed the teaching body because each department thought it had obtained all that it could get, but which, as an educational system, was not likely to be defended by any of the faculty members who adopted it. Such a curriculum, now almost obsolete in our colleges, was well enough for the student whose tastes happened to lie along certain conventional lines, and for his docile fellow, without definite aims of his own who was willing to do, without protest, exactly as he was told; but it had the defect of measuring all students with the same yardstick, of requiring of all the same performance, of assuming that personal tastes and preferences are of no consequence, of encouraging the idea that smattering trivialities in many fields constitute educational advance, and of wasting a tremendous amount of time in required subjects in which the interests of the individual students could not be aroused.

FREE ELECTION SYSTEM

The second system is that of free and unlimited election. The resources of the institution are placed at the disposal of the student. He is told to take whatever subjects he likes and the amount of each is left to his own discretion. This theory is admirable in practice, and works excellently with the earnest student who has some wisdom and definite and worthwhile ideas of what he wants to do. Unfortunately the race of students, much like the rest of humanity, contains large numbers of men who seek the easiest way; a malady which is tremendously contagious in the close association of a college. As a result, it was found that for too many men a college career under this system consisted of an uncorrelated collection of elementary courses, selected, so far as possible, to involve the minimum of effort. When enough of these had accumulated to the credit of the student, the degree was awarded as a matter of course, but it could not be said to indicate any particular intellectual advance on his part.

The advantages and disadvantages of the two systems are now so well recognized that in most American colleges the attempt has been made to avoid the defects of each by the combination of the two. These efforts have been more or less successful. Two difficulties remain, however. The first is the prevailing system of credits by which an accumulation of "hours" or "points" or both, attained in individual courses (in their summation) is the prerequisite for the degree. As a result, the attention of the student is directed mainly to these credits, and he forms the idea, not without reason, that his principal aim in every course is to attain the "hours" which it brings. Consequently, in his mind a course once "passed" is, as a matter of fact, really passed; he need never return that way again. Of course, this bookkeeping has nothing to do with education, although it may be convenient for the registrar. The second difficulty, always emphasized by the foreign observer of our system, is that it is a thing of shreds and patches, of smatterings without objective or focus; that the student never really knows anything profoundly and well. Even if the attempt is made to correct this difficulty by systems of concentration or "majors," these majors are divided into individual courses, each with its points and credits, and each "passed" when it is once over. The student is never required to view the subject as a whole.

A NEW CURRICULUM

In the latest extensive revision of the curriculum of Dartmouth, made in 1925, the faculty endeavored to formulate a system in which, so far as possible, these weaknesses should be minimized. The guiding principle adopted was simple; namely, that the course of study followed by each student should be based upon his prevailing interest; when that interest was once discovered, he should work intensively in that chosen field; and that, at the end, his command of the subject as a whole, and not merely individual courses in it, should be tested by a comprehensive examination. To carry out this plan effectively the first two years must be devoted to the discovery of the particular field in which the student's interest lies; and a goodly portion of the last two years are then applied to intensive cultivation of it. At the same time, a considerable portion of the course must be open to free election, so that the student may pursue subjects either of a general nature or those collateral to his specialty. Accordingly, his choice of the main subject to which he will devote his efforts is entirely free: he is aided in choosing it by the requirement that in the early years of his course he shall distribute his efforts among various fields: when the major is chosen, he must pursue it intensively and must show reasonable acquirements in it as a whole.

In detail, the first two years at Dartmouth require one year-course in English one year-course in general orientation in the social sciences and either a second yearcourse of such orientation, or one chosen from some particular social science; two year-courses chosen from a group consisting of mathematics and six natural sciencesand two year-courses in the languages and humanities. Three year-courses in this period are thus open for unrestricted election. At the end of sophomore year the student selects his major, usually a subject which he has already begun. A minimum of two-fifths of his time in junior year and three-fifths in senior year is devoted to courses in this department: one of them in senior year being an advanced integration course, variously conducted in different departments, designed to knit together the specialized information received in the individual major courses. Not all majors are confined to single departments. A growing tendency exists, particularly in the social sciences, for the institution of topical majors, cutting across departmental lines, and centering the intensive work of the student upon a particular subject of large importance, to which each of a number of departments involved makes its special contribution, the whole being unified by a common plan of administration.

At the end of senior year comes the comprehensive examination, the passing of which is indispensable for obtaining the degree. These tests, consisting of three or four parts given on different days, are designed to enable the student to show, not what he does not know, but what he knows well. They cut across the lines of departmental courses, and are sufficiently inclusive to enable the candidate for the degree to reveal his strength, if he has any, rather than his weakness. However, the object of the test, in the main, is not this—rather it is to place before the student throughout his course, the necessity of considering his subject of specialization as a whole, with all its interplay of relationships, and not to form the false conclusion that learning. is made up of separate units, composed of isolated parts, each with its special and independent requirements.

T his curriculum has now been tested sufficiently long to enable the assertion to be made that it has answered its purpose with reasonable efficiency. Its principal merit is its effect on the outlook of the student, which, on the whole, has been gratifying. Such direct tests of scholarship as may be applied to it, such as the attainments and points of view of Dartmouth graduates who enter graduate or professional schools elsewhere, in competition with men from other colleges, trained under different systems, has been encouraging. Like the curricula of all live colleges jt is constantly being changed and improved in its details, but the general principles upon which it rests seem worthy of preservation.

HONORS COURSES

It is obvious that in college the men of superior intellectual capacity deserve special treatment, involving a large degree of individual attention. Such men at Dartmouth, if they so desire, and if their field of concentration is in a department in which such work is advantageous, are removed in their major subject from the general run of the student body. They are required to attend none of the ordinary courses in that department, unless they wish to do so, but are given instruction individually or in small groups by instructors specially assigned for the purpose. Such students have a greater degree of freedom and are not so closely bound by normal class restrictions as are their fellows, but they are required to take the same comprehensive examination. In some departments, such as the natural sciences, sufficient advance beyond the elementary stage of the subject is not made by students by senior year to allow such a system to operate, and honors courses are not open to majors in these subjects. Nevertheless, in the whole College approximately 100 members of the two upper classes are in the honors group.

STUDENT EXPENSES AND FINANCIAL AID

The yearly expense of the undergraduate at Dartmouth is subject to so many variables resulting from differences of taste and of individual means that definite classification is difficult. The minimum is estimated as $110, with a more liberal allowance fixe'd at $1500. The tuition fee is $450. Room rentals range from $80 to $300 per person. The cost of other items—board (except for freshmen, for whom it amounts to about 1270 per year), books, laundry, clothing, travel, and other personal and social needs, varies widely with the individual undergraduate.

The allotment of scholarship and loan funds (financial aid) to students who require such assistance is the responsibility of the Committee on Scholarships and Loans, with the chairman, who is also director of personnel research, as the administering officer. In considering such requests the College takes into account the financial need and the general record of the applicant.

During the last few years, the number of men who have been given financial aid on either the so-called scholarship funds or loan funds has increased to approximately 20% of the total enrollment; likewise, there has been a gradual increase in the amounts granted per man. The College has always followed the policy of granting aid through the entire four years if a student on aid continues to meet the requirements, and still is in need of such assistance. In other words, when an entering freshman is accepted for aid, he is thought of in terms of a four-year investment. This carries the obligation of providing him during his four years with somewhere between $BOO and $2OOO, depending on the amount of assistance needed annually. It is therefore imperative that great caution be exercised in making selections among the entering freshmen. During the last few years, somewhat over twice as many applicants have applied as could be approved.

Dartmouth has adopted the policy of assisting a limited number of undergraduates adequately rather than spreading the amount of aid thinly over a larger group. The purpose is to continue to limit the number of men who are to receive aid, but also to increase the individual amounts so that no undergraduate will be obliged to work outside longer than a maximum of three hours daily.

Scholarship aid has been financed through certain definite loan funds and through the income from funds specifically set aside for scholarships together with an annual appropriation by the trustees from current funds to cover the remainder of the program. Unfortunately, the income from loan funds and scholarship funds represents roughly only about one-half of the total amount that is needed, which means that there has been a very heavy annual drain on the general income of the College.

On the average, the total amount devoted annually by the College to scholarships and loans is now about $125,000. This figure does not include the remuneration received by needy students from positions outside—such as waiting on table, working around town, and other similar means of self-support. Loans are payable not later than five years after graduation. The record of repayment on such loans is high.

The College at present has a limited number of regional scholarships varying from $500 to $700 from the states of New Hampshire, Connecticut, New York, and California, and the region of Chicago. These scholarships are awarded by the President on recommendation of the Committee on Scholarships and Loans. It is the hope that funds may be made available so that such scholarships may be instituted for an increased number of states or areas of the country.

RESOURCES OF THE COLLEGE

On June 30, 1937, the estimated value of the educational plant of the College was $7,013,400. The book value of investment assets was $17,428,000. The total value of all assets, including sundry advances and cash on hand, was $24,581,000. Like other accumulations of capital a very considerable decrease of income was experienced during the recent years of depression. In 1936-1937 the return from investments amounted to $661,000 or 3-79% on the. average capital value of investment assets throughout the year.

The business of investment of college funds is in the hands of the Trustee Committee on Investments, with the treasurer of the College as its active agent.

While generous gifts have been made by benefactors of the College throughout its entire history, it is nevertheless true that the endowment of the institution is considerably less than that of many other privately endowed universities and colleges for men in its own class. This relative paucity of endowment places before the trustees a serious problem, in view of their determination to make the work at Dartmouth at least equal in grade to that offered by others which have the advantage of larger means. It may safely be said that, within its chosen field, the aim of the trustees has been fully realized; that the effectiveness of Dartmouth as an educational institution is recognized as being on a parity with that of any of its friendly rivals. That result has been accomplished, however, only by the most careful husbanding of funds, and it has involved many sacrifices and expedients which, under better financial conditions, would not be considered satisfactory or even tolerable.

The direct application of endowment can best be estimated by consideration of the figures relating to student costs. In 1936-1937 the College expended for each student 1776.17. Deducting scholarships and loans, the individual undergraduate himself paid, on the average, $378.91, or 48.82% of the whole. The remainder, $397.26, was derived from the return from endowments and from gifts to the institution for current use.

INCOME AND EXPENSE

The income and expense account of the year 1936-1937 may be considered as typical. Income Students $ 918,100.61 Investments, Net 661,052.91 Miscellaneous 90.655.99 Gifts (Current) 210,852.48 $1,880,661.99 Expense Instruction and Libraries . . $1,163,944.76 Administration 166,457.08 General 171,101.08 Health Service 89,056.11 Plant Operation and Maintenance 197,996.90 Restricted Current Funds. . 44,857.89 Annuities, Add. to Principal 47,248.17 $1,880,661.99

It is to be observed that expense for instruction and administration amounts to 71% of the total.

For more than twenty years Dartmouth College has operated without a deficit, other than one of small amount in two. or three cases, in each case made up during the succeeding year. Indispensable in attaining this desirable end is the Dartmouth Alumni Fund—an annual contribution of money by the alumni of the College for immediate and unrestricted use. It has never seemed feasible to the trustees to institute and carry on among Dartmouth alumni a highly organized drive for endowment funds, as many other colleges have successfully done. The alumni of the College, as a class, unlike those of some other institutions are for the most part men of moderate prosperity rather than of large wealth. They are ready and willing to give moderate amounts annually, which may be regarded as income; while they might be embarrassed by requests for large sums, to be held as capital endowment. It is obvious that the total sum collected annually in this way varies with economic conditions and the prosperity of the country as a whole. In recent years the income of the fund rose to a maximum of $129,786 in 1929 and fell to its lowest point of $67,200 in 1933. In 1937 the contribution was $103,936.73 with a net return, after deducting expenses and adding the income of certain special funds allied with this foundation, of $101,111.39. Highly satisfactory is the number of contributors (7,942 in 1937), which is 72% of the total number of living graduates; a higher percentage than has been attained by the Alumni Fund of any other college. From this income, what would otherwise have been a deficit of about $80,000 was avoided.

The importance of the Alumni Fund can hardly be overestimated. While it amounts to but 5% of the total income, its availability is such that it constitutes a resource not to be measured by its actual yield. To quote the treasurer of the College, "it has made it possible for the administration to go forward with plans which have represented real progress, with expenditures which otherwise would have to be deferred or eliminated So many different decisions are affected by the availability of the Fund that it truly represents a cross-section of the whole financing of the College. The application of the Alumni Fund over so broad a base has made the amount contributed of the greatest possible usefulness to the College."

Even during the recent depression the institution, although much buffeted, staunchly weathered the storm. The number of undergraduates was rather increased than reduced, and income from tuition suffered very little decrease, although the demand for scholarships became much larger, and difficulty was experienced in renting the more expensive college rooms. Income from investments of course declined sharply and a corresponding reduction of the value of stocks and bonds occurred. The institution met the crisis resulting from the reduced income in the only sensible way; by reducing its expenses. Outlay for purposes other than educational was radically cut: for one year faculty salaries were somewhat reduced, although in the main, they were largely restored at the end of that period. The utmost economy prevailed in all expenditures, except those for scholarships, which were actually increased. The income from the Alumni Fund declined sharply, but the amount received was of even more service than had previously been the case. At no time did a permanent deficit occur, and no debt accumulated as a result of the reduction of revenue.

The pleasing picture of solvency presented above should be given its real significance. It is a result of the determination of the trustees to limit the activities of the institution to its resources and their refusal to embark in undertakings beyond College means. It indicates careful financial management, the judicious handling of funds, and persistent and successful efforts to make every dollar do its full share of workBut it represents other conditions not so desirable nor so productive. In many cases it means the application of policies which the trustees themselves would be the firs' to characterize as penny-pinching; and that application is made, not because these policies are regarded by any one as desirable or even successful in contrast to more liberal ones, but because they are imperative. It means that certain facilities, which everyone knows would yield highly satisfactory returns, must be postponed for lack of resources to carry them out. It means that certain well-thought-out educational policies must be deferred. It means that, while the work of the institution is effective, while it holds an entirely creditable position among the educational institutions of the country, it might be improved easily and notably along many lines, recognizable by all who have to do with its management, had it a more generous supply of funds.

CONCLUSION

In the first part of this discussion the statement was made that a responsibility rests upon any privately endowed institution to show prospective donors that it is using the means now at its disposal with the utmost possible efficiency. If it can meet that test, it has a claim for further benefactions. These pages set forth the case of Dartmouth College in meeting this issue. From the discussion it appears that the guiding policy of the institution is, first, to form a definite, well-considered and practicable plan of what its purpose shall be and what it shall endeavor to do. Then, and then only, it strives to formulate the most effective method of attaining the desired end. That method being tentatively adopted, it is continually subjected to test, with no hesitancy in adopting reasonable modifications, so that it may operate with the maximum efficiency.

In brief, the following claims have been made:

1 Dartmouth College is one of the oldest educational foundations of the land; its highly creditable record in the first one hundred and seventy years of its history gives warrant to the belief that its future will be equally serviceable.

a The trustees have determined definitely what the scope of the College shall be, have consistently kept the institution within these boundaries, and have insisted that high efficiency shall prevail in all work done within its chosen field.

3 The organization of the trustees eventually proved inelastic. Therefore, modifications have been made to ensure a more representative board, with the virtues of sufficient continuity still preserved.

4 The type of teacher who best fits the requirements of the institution has been determined and every endeavor is made to secure and retain teachers of the chosen type. 5 The optimum size of the College has been determined, and the undergraduate numbers kept at that point.

6 The type of student upon whom the College can act most effectively has been determined, and a system of admission planned and instituted to obtain that type, with successful results.

7 The educational aim of the institution in the development of the student has been determined and a curriculum instituted to attain that aim, with successful results.

8 The special responsibility of the Col- lege to men of high intellectual capacity has been recognized, and honors courses and senior fellowships instituted to meet that responsibility.

9 The place of intercollegiate athletics in the organization has been determined and a system of athletics encouraged, but re- stricted to that place. At the same time full athletic opportunities are placed at the dis- posal of students who do not engage in intercollegiate competition.

10 The special environmental and climatic advantages of Dartmouth have been recognized and the Outing Club instituted to utilize them.

11 The non-curricular interests (music, drama, etc.) of the undergraduates have been recognized and opportunity given to gratify them.

12 Opportunities for religious development have been brought into consonance with the conditions of the time.

13 The importance of reasonable social opportunities has been recognized, and proper social activities encouraged.

14 The fraternity system has been recognized as not rising to its full opportunities and is now being examined with the hope that it may become more serviceable.

15 Educational equipment has been modernized, enlarged, and, with a few exceptions, made adequate to the needs of the institution.

16 The responsibility of the institution for the provision of suitable living quarters and dining facilities has been recognized, and large appropriations of College funds have been made for these purposes.

17 The special responsibility of the College for medical service has been recognized and is now adequately met.

18 Scholarships and other financial aid to students have always been recognized as a primary responsibility of the College and have been supplied even further than the financial resources of the institution seem to permit.

19 The Associated Schools have been restricted to those three which grew naturally from conditions prevailing in Hanover. In them the highest standards are maintained.

20 The endowment of the College, while inadequate, has been wisely used. 21 The financial management of the College has been characterized by economy, efficiency, and the most painstaking use of all available resources.

As a result of these considerations (and others which cannot be included in this brief discussion), with all modesty and yet with confidence the College appeals to those whose interests lie in higher education, so that the promise of service in the future may be even greater than the record of service in the past.

THE SOUL OF THE COLLEGE

In the foregoing analysis of the College, its purposes, its policies and its aspirations, the attempt has been made to state as objectively as possible the facts which make the institution what it is. But such a picture is not complete if the emotional element is ignored. It has been truly said that no group of men can be associated together for any purpose whatsoever without developing a soul of its own, and oftentimes the soul is the most important factor in forming judgment of the group.

For the College is a continuing institution; its vitality is not limited by time or space; it holds steadfast to its purpose and maintains its ideals, unaffected by the ephemeral lives of men. It is true that its impact is ever changing, its methods are continually revised that it may meet more effectively the demands of the times. But its one vital principle has never changed in all the years of its history—its purpose has never altered from that established by Wheelock in the genesis of the College: the ideal of maximum service to the social order, and of maximum efficiency in its impact upon the generations which seek its fostering care. Its motto, taken from St. John, "Vox Clamantis in Deserto"—the Voice of One Crying in the Wildernessis even today truly descriptive. Dartmouth still enjoys a fine measure of isolation; it is not surrounded and shouldered by the more tawdry aspects of modern civilization; its campus is bathed with the clean winds of the mountains; it preserves a democracy which cherishes the poor as highly as the rich, and the rich as highly as the poor; its atmosphere is both catholic and tolerant. Amid these conditions and with these advantages it strives with a unified purpose to attain the aims which have been its aims for the more than a century and a half of its existence, and it strives to attain these aims with sympathy, intelligence and vigor.

IT SHALL ENDURE

But while the institution is eternal, it lives through the activities of successive generations of men. They rise, they do their work, they pass from the scene, and the College has its being and advances to greater spheres of service through their efforts. Their animating purpose has always been that the institution shall be strong; strong that it may be effective. It was so with Wheelock with his Indian School in Connecticut; it was so with his Indian disciple, Occom, in England, who moved with his sincerity multitudes of men from the king on his throne to the humble cloth weaver in the rural village; it was so with Wheelock again in his heroic and successful struggle to establish a college in the northern wilderness; it was so with his son, John, who raised the College from abject poverty to a condition of equality with, the best educational institutions of the land; it was so with Daniel Webster, in his defense of his alma mater in the Dartmouth College Case, famous in the realms of constitutional jurisprudence; it was so with Nathan Lord, who for thirty-five years, with tireless industry and single-minded devotion, administered the institution in difficult times; it was so with William Jewett Tucker who, with inspired vision and keen practical sense, gave to the College a new birth; it is so today with Ernest Martin Hopkins, twenty years president of the College, guardian of its interests in the period of full flowering; it is so with the great body of graduates of whom seven out of ten come to the financial aid of the institution every year through gifts to the Alumni Fund. These men and thousands of others, trustees, faculty, alumni and undergraduates, at all periods of its history, each serving in his own sphere, have made Dartmouth what it is.

For in the feeling which binds the son of Dartmouth to his alma mater lies the soul of the College. It is compounded of too many elements to be adequately portrayed. The bracing cold of the Hanover winter, and the balmy air of its early summer; the feeling of the spiritual presence of the figures of the past within its halls; the compact and self-contained community life; the binding force of daily companionship in classroom and athletic field, in tramps over the New Hampshire hills and in the thousand and one interests of daily life; undergraduate friendships, the most lasting of all; the joy and pride of the alumnus in his college, with cherished remembrances of his own student days: all these and a thousand other factors combine to form that elusive whole. To these men who love Dartmouth its very name is like the stirring of martial music; from them the institution evokes a truly filial love; to them their alma mater is something more than a college—it is a religion. That is the true Dartmouth.

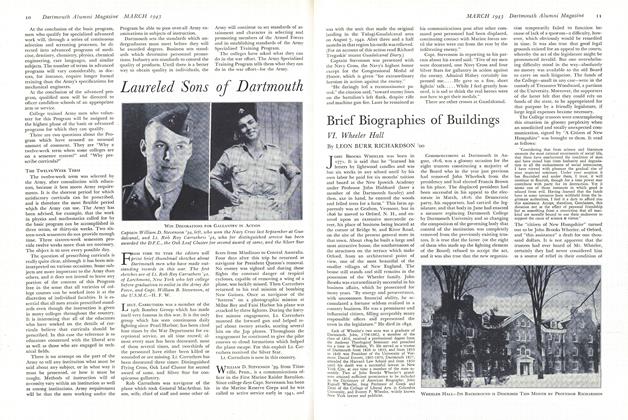

Plans Are Being Drawn for the Proposed Theater and Auditorium, An Important Need of the College[lllustration from "Needs of Dartmouth College," published by the Alumni Council.]

Architect's Design for the Important Additions To Modernize Wilder HallOne of the Most Pressing Needs [lllustration from "Needs of Dartmouth College," published by the Alumni Council.]

The Architect's Plan for Adding to the Existing Inadequate Building, Which Is Shown at the Left[lllustration from "Needs of Dartmouth College,' published by the Alumni Council.]

Professor of Chemistry, Member of the Alumni Council

ONE OF THE introductory paragraphs in the Alumni Council's booklet, "Needs of Dartmouth College," expresses pretty well what alumni have in mind when they join in the hope that the required additions to plant and endowment may be secured. We quote: "The administration of President Hopkins began in 1916. His strong leadershipduring the intervening years has built a'New Dartmouth' on the sound foundations of the old historic college of liberalarts. Tremendous advances have beenmade during this period but with only themost slender reserves, a?id at times withoutany reserves at all. Fortunately there areyears ahead when President Hopkins cancontinue to strengthen the College at everyweak point; ivhen he can bring to fulfillment some of his dreams for increasing thesecurity of the institution; when he mayfinally achieve his goal of increased salariesfor members of the faculty; when he andthe trustees may reach many of the objectives that are described in the pages of thisfolder of needs of the College. These thingsare the keen desire of alumni and friendsof Dartmouth. Their realization is essential to the cumulatively productive life ofthis College."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassian

January 1938 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

January 1938 By Eugene D. Towler -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

January 1938 By F. William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

January 1938 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

January 1938 By H. Philip Patey -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1925

January 1938 By Ford H. Whelden

LEON BURR RICHARDSON 'oo

Article

-

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

January, 1926 -

Article

ArticleChase's History Reprinted

November 1928 -

Article

ArticleCarnegie Report

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

Article"Cheer and Warmth"

December 1954 -

Article

ArticleConfessions of a Former White House Intern

APRIL 1998 By Monica Oberkofler -

Article

ArticleHonor by Degrees

MAY 1997 By Noel Perrin