General Electrics chief "eco-imagineer" talks about making profits by going green.

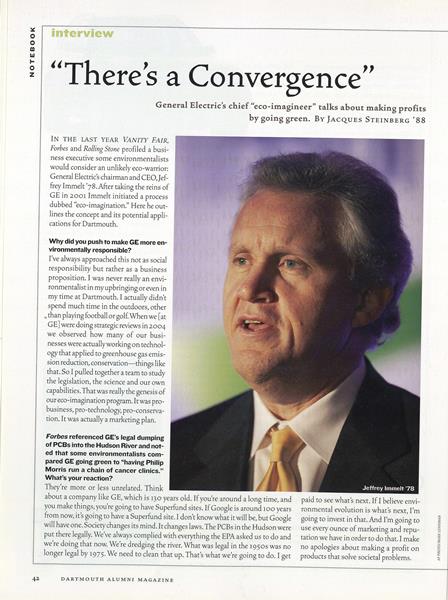

IN THE LAST YEAR VANITY FAIR,Forbes and Rolling Stone profiled a business executive some environmentalists would consider an unlikely eco-warrior: General Electrics chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt '78. After taking the reins of GE in 2001 Immelt initiated a process dubbed "eco-imagination." Here he out-lines the concept and its potential applications for Dartmouth.

Why did you push to make GE more environmentallyresponsible?

I've always approached this not as social responsibility but rather as a business proposition. I was never really an environmentalist in my upbringing or even in my time at Dartmouth. I actually didn't spend much time in the outdoors, other than playing football or golf. When we [at GE] were doing strategic reviews in 2004 we observed how many of our businesses were actually working on technology that applied to greenhouse gas emission reduction, conservation—things like that. So I pulled together a team to study the legislation, the science and our own capabilities. That was really the genesis of our eco-imagination program. It was probusiness, pro-technology, pro-conservation. It was actually a marketing plan.

Forbes referenced GE's legal dumping of PCBs into the Hudson River and noted that some environmentalists compared GE going green to "having Philip Morris run a chain of cancer clinics." What's your reaction?

They're more or less unrelated. Think about a company like GE, which is 130 years old. If you're around a long time, and you make things, you re going to have Superfund sites. If Google is around 100 years from now, its going to have a Superfund site. I don't know what it will be, but Google will have one. Society changes its mind. It changes laws. The PCBs in the Hudson were put there legally. We've always complied with everything the EPA asked us to do and we re doing that now. We re dredging the river. What was legal in the 1950s was no longer legal by 1975. We need to clean that up. That's what we're going to do. I get paid to see what's next. If I believe environomental evolution is what's next, I'm going to invest in that. And I'm going to use every ounce of marketing and reputation we have in order to do that. I make no apologies about making a profit on products that solve societal problems.

How might Dartmouth apply some of what you learned at GE?

Increasingly we need to make sure liberal arts embrace the study of science, particularly science we think is going to be important for the next 20,30,40 years. I think there's a convergence between health care, environmental science, chemistry, biology, public policy. Environmental science and environmental policy are among the themes of the next 50 years that Dartmouth needs to train students to be aggressively pursuing. I've worked a little bit with President Jim Wright to frame the investments the trustees want to make in the life sciences. I've looked at it both from a health care standpoint and also from an environmental standpoint as a way to get people from the Thayer School, people from the chemistry and biology area and people from the Medical School to all come together to make an investment and train kids for where they need to go.

What opportunities does Dartmouthhave to become a greener institution?

You could power the place using a couple of biomass turbines. They would work on waste streams—human waste or trash- or they could work on ethanol. Solar energy could be used, although that's difficult during the winter months in Hanover. Dartmouth could tie into a utility to do wind. I actually sent some people from GE up to meet with people on campus about ways we can reduce the Colleges greenhouse gas emissions.

How did you like Rolling Stone naming you one of "25 leaders who are

fighting to stave off the planetwide catastrophe?"

It helped me with my daughter, for sure. She's 20. If you think about environmental technology or awareness, it is one of those things that is age-dependent. When I speak with GE employees who are 60 or 65 years old they have no instinctive feel that global warming and green- house gas emissions are at all something we should be thinking about or worried about. If I talk to an employee who is 25 years old they think this is the best thing the company has ever done. One of the things you always try to grapple with as you age in business is staying contemporary. I still read Rolling Stone. I still read FastCompany. Not just because it's fun—the best new ideas are likely going to come from places like that.

Will Dartmouth students respond toyour ideas?

Kids today are so in touch with the environoment —much more than when I was on campus. Whether it's conservation or alternative energy, a college campus is the easiest place to generate interest. What's more important at a place like Dartmouth is making sure that the curriculum is in tune with where society is going. Society is moving closer to the economics of scarcity, whether it's in water, whether it's in energy, whether it's in environmental capability. I think the bigger contribution a school like Dartmouth can make is inside people's minds, more so than how many compact fluorescents they use.

"Society is moving closer to the economics of scarcity."

Jacques Steinberg covers television and the media for The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

SPORTS

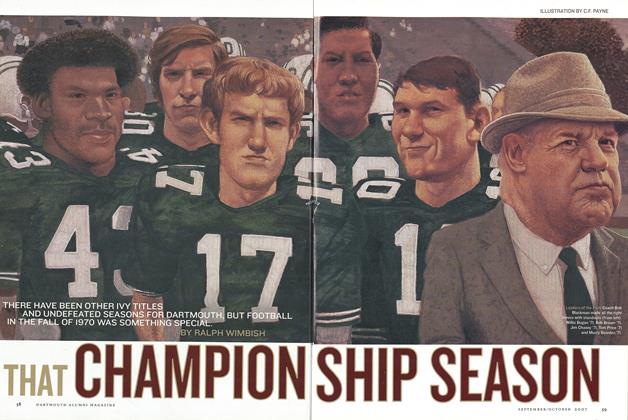

SPORTSThat Championship Season

September | October 2007 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

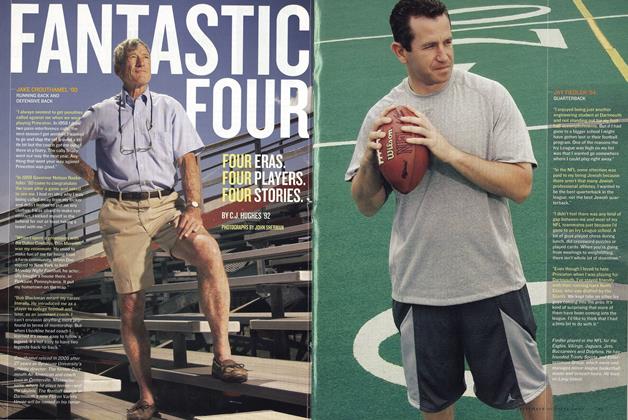

FeatureFantastic Four

September | October 2007 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

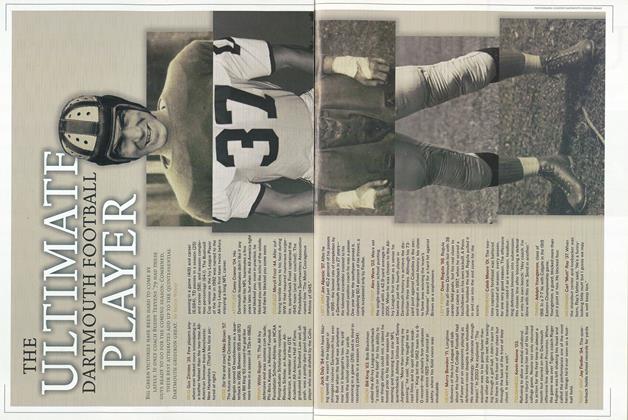

FeatureThe Ultimate Dartmouth Football Player

September | October 2007 By Bruce Wood -

Feature

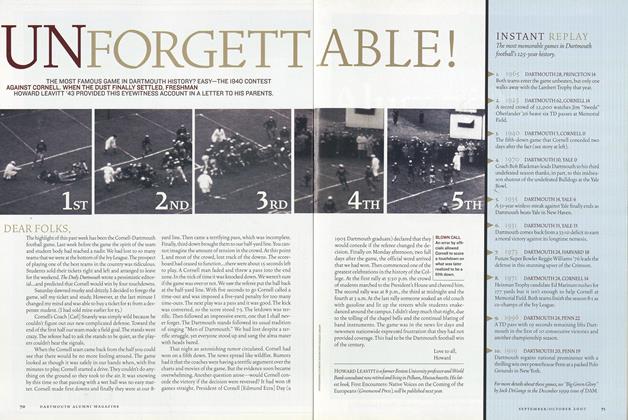

FeatureUnforgettable!

September | October 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

SPORTS

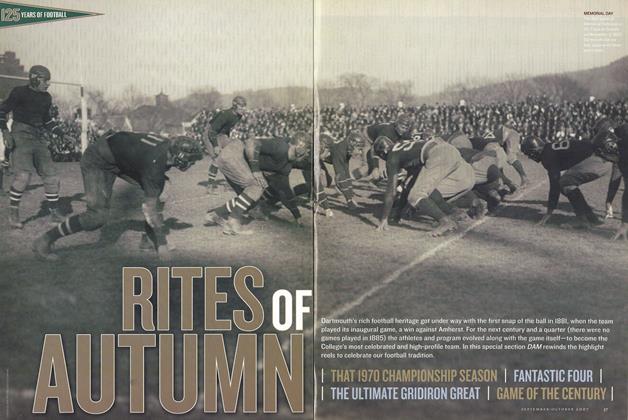

SPORTSRITES OF AUTUMN

September | October 2007 By Courtesy Dartmouth College Library -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74

Jacques Steinberg '88

-

Cover Story

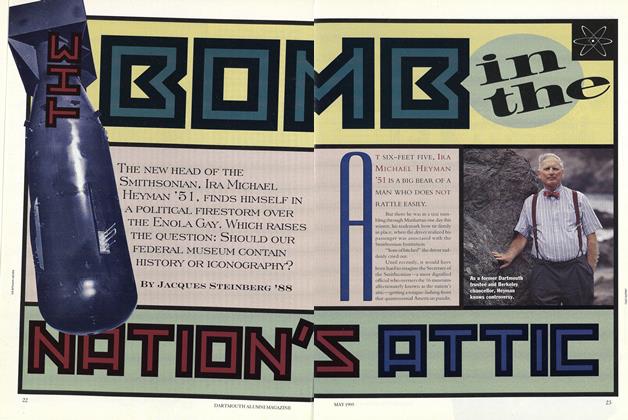

Cover StoryThe Bomb in the Nation's Attic

May 1995 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationPaul Binder '63

Nov/Dec 2000 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Continuing Education

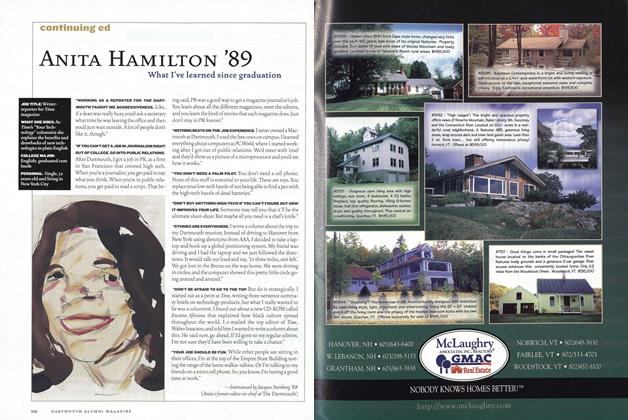

Continuing EducationAnita Hamilton '89

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Continuing Education

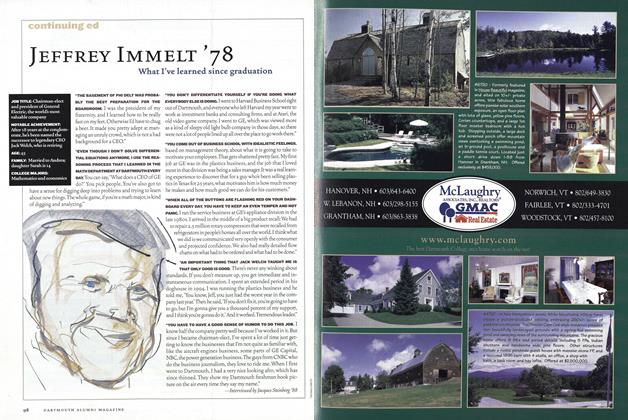

Continuing EducationJeffrey Immelt '78

May/June 2001 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Interview

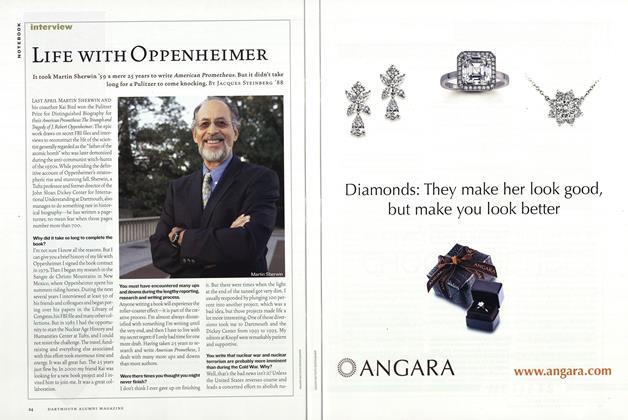

InterviewLife with Oppenheimer

Jan/Feb 2007 By Jacques Steinberg '88

Interviews

-

Interview

InterviewA Fan's Notes

Sept/Oct 2007 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“The Pool is So Deep”

July/August 2007 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Interview

Interview"Nuanced Decisions"

May/June 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

Interview

InterviewLook Who’s Talking

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Madison Wilson ’21 -

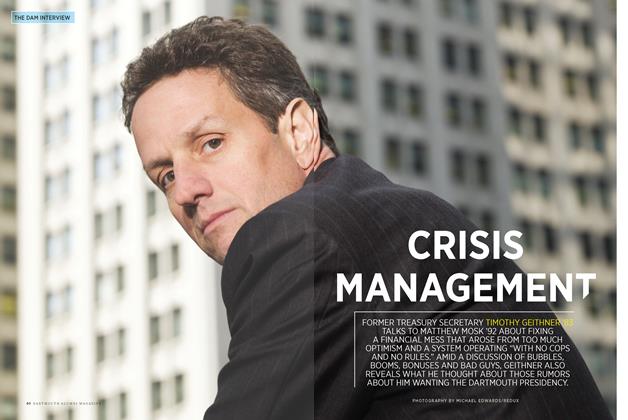

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWCrisis Management

July | August 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Interview

Interview“An Improbable Opportunity”

July/August 2012 By Sean Plottner