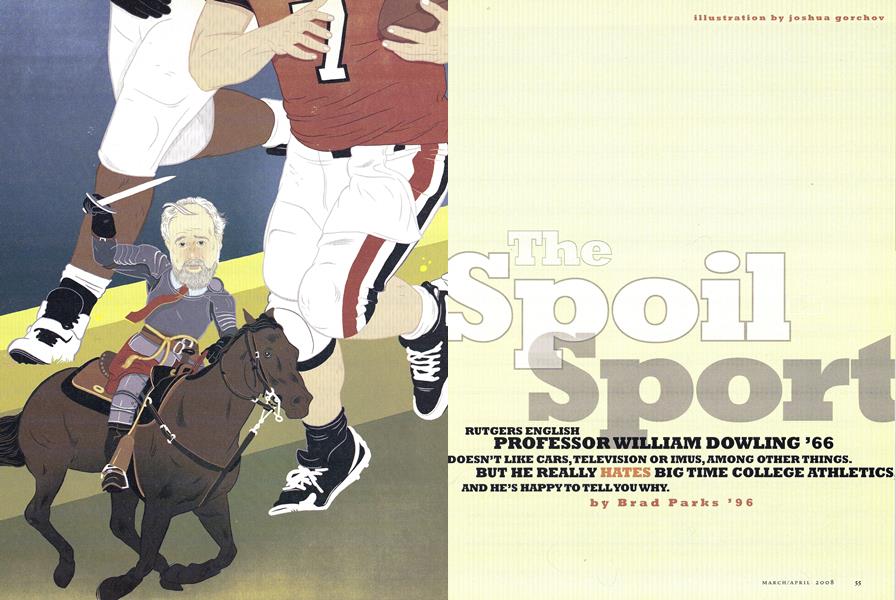

The Spoil Sport

Rutgers English professor William Dowling ’66 doesn’t like cars, television or Imus, among other things. But he really hates big time college athletics and he’s happy to tell you why.

Mar/Apr 2008 Brad Parks '96Rutgers English professor William Dowling ’66 doesn’t like cars, television or Imus, among other things. But he really hates big time college athletics and he’s happy to tell you why.

Mar/Apr 2008 Brad Parks '96RUTGERS ENGLISHPROFESSOR WILLIAM DOWLING '66DOESN'T LIKE CARS, TELEVISION OR IMUS, AMONG OTHER THINGS.BUT HE REALLY HATES BIG TIME COLLEGE ATHLETICSAND HE'S HAPPY TO TELL YOU WHY.

TO R CERTAIN SET OF COLLEGE SPOUTS BOOSTERS, the harangue of William Dowling has long been that 6 a.m.jackhammer outside the bedroom window—irritating, uninvited and incessant. An English professor at Rutgers University, Dowling in 1997 founded Rutgers 1000, a group of students, alumni and professors with the quixotic goal of getting the state university to step away from Division I-A athletics.

His task was basically hopeless. Rutgers, which once played a schedule of Ivy and Patriot League schools, sought the brass ring of big-time college sports more than a decade ago. It spent millions on scholarships, coaches' salaries and stadium refurbishments, gambling that the revenue and publicity from bowl berths and television appearances would make the investment pay off.

Dowling has a word for this: prostitution. His stance, briefly, is that no college or university should be selling itself as a sports entity. Those that do inevitably end up offering scholarships to what Dowling calls "hired morons"—the NCAA, prefers the term "student-athletes"—and pouring money into shoulder pads and weight rooms that should be budgeted for professors' salaries and library books. The prioritization of athletics over academics leads to a brain drain of talented students and faculty and a perversion of the stated mission of higher education, he says.

For a time Dowling's argument gained some support at Rutgers, mostly because the football team stunk worse than any turnpike refinery. Then the football team got good. Then it got very good, cracking the national rankings and becoming the darling of a state that never had much to call its own athletically. Suddenly Dowling was just the guy at the keg party reminding everyone how many brain cells they were killing.

But he was never accused of malice, not until this past September. In the process of peddling a new book—Confessions of a Spoilsport:My Life and Hard Times Fighting Sports Corruption at an Old EasternUniversity—Dowling was asked by a New York Times reporter about the claim from boosters that athletic scholarships provide educational opportunities to minorities.

"If you were giving the scholarship to an intellectually brilliant kid who happens to play a sport, that's fine," Dowling replied. "But they give it to a functional illiterate who can't read a cereal box, and then make him spend 50 hours a week on physical skills. That's not opportunity. If you want to give financial help to minorities, go find the ones who are at the library after school."

Suddenly, Dowling—who had never been labeled as anything more than an intellectual snob, an elitist or an aging crackpot—was being called something far worse.

A racist.

Rutgers President Richard McCormick called the comment "inaccurate and inhumane" with a "racist implication that has no place whatsoever in our civil discourse." Floyd Keith, executive director of the Black Coaches & Administrators, said it "reinforces an unfounded and inaccurate public perception about the studentathlete and, in particular, the black student-athlete." Steve Politi, a sports columnist for The Star-Ledger, likened Dowling to shockjock Don Imus, who earlier in the spring was fired for referring to members of the Rutgers women's basketball team in derogatory terms.

While the rest of the world connected the dots—the mere combination of "illiterate" and "minorities" in one quote was enough to send the PC police to their squad cars—Dowling remained mystified about all the fuss.

He says he was not talking about all black athletes or even all Rutgers athletes but, rather, one athlete in particular: a North Carolina State basketball player from the 1980s who, it was later shown during a trial, really couldn't read the back of a cereal box. Dowling then launches into a red-faced rant about how athletic scholarships have been a disservice to minorities, particularly to inner-city blacks who have been led to believe dribbling a basketball is their only path to college. He dismisses the charge of racism, noting he did civil rights work in the South during the 19605, after all.

Dowling also found some amusement in the controversy. "That moved 1,000 books in four days," he says. "My publisher asked me, 'ls there any way you can get them to accuse you of child molestation? We'd really sell books then!' "

He's joking, of course—sometimes, the side of him that once edited the Jack-O-Lantern at Dartmouth still comes out to play. It only takes a quick conversation with Dowling to realize selling books is not particularly high on his list of priorities. Nor, for that matter, is winning popularity contests. Ideas are what matter to him. He lives his life by them, even though most of his ideas make him, by the standards of American mainstream culture, something of a nut.

He does not own a television or listen to radio. He retreated from e-mail a few months back when a virus hijacked his computer, and he vows not to return. His friends joke he prefers Latin to English. When he speaks of Yahoos, it is a reference to Gulliver'sTravels, not the Internet.

He does not drive a car, and the story behind this fact is typical Dowling. As he tells it, his parents had given him a car as a graduation present. On his trip from Hanover to Cambridge, where he was to start a Ph.D. program in English, he became increasingly terrified the closer he got to Boston.

"Finally I said, 'God, if you get me out of this, I'll never drive again,' " Dowling says. "I'm the rare person who keeps his promises to God."

He's also the rare person who turned down a chance to appear on 60 Minutes because he believes CBS, which paid the NCAA $6 billion to televise the March Madness basketball tournament for an 11-year period, is helping destroy higher education. He also turned down The Daily Show, ESPN's Outside the Lines and other priceless opportunities for free publicity.

"I tell my students that my job is to undo the cumulative effect that 18,000 hours of television has had on their brains," Dowling says. "So I'm not going on any television show. Not as long as television remains an open channel of cultural sewage pouring into the minds of young people."

He pauses, then admits, "My publisher isn't too pleased about any of this."

There are times when his eccentricities can come off as schtick. He pronounces the name of the shock-jock "Eemus" instead of "Imus," though he has been corrected numerous times. He acts the part of the mad professor, with the Walt Whitman beard, the hastily knotted tie and the propensity to forget life's mundane details. He delights in telling a story about not knowing the difference between CNN and ESPN. Yet for as much as he claims to be out of touch with modern society, he delivers an excoriating anti-pop-culture diatribe that references everything fomAmerican Idol to Britney Spears.

"It's not by accident he doesn't drive a car. And it's not by accident he'll tell you he doesn't drive a car within the first 20 minutes of when you meet him," says Dick Seclow, a 1951 Rutgers graduate and the alumni coordinator for Rutgers 1000. "He likes that he has an idiosyncratic lifestyle. And he is deeply committed to his beliefs."

As a scholar Dowling is first-rate, the author of 11 books and a veteran of a half-dozen fellowships. His students adore him—well, all except for the ones who hate him. He's been known to flunk anyone he suspects of loafing intellectually. He teaches a two-course series that English majors refer to as"literary boot camp." Yet those who survive end up listing him as their favorite professor, one who forces them to think critically. He and his wife of 40 years, Linda, do not have children, but he thinks of his students in paternal terms. Once a week he reprises one of his favorite Dartmouth traditions, Sanborn tea, in his office. He has a reputation as an enthralling lecturer.

"You're talking about a guy who regularly professes his metaphysical love for [Pride and Prejudice protagonist] Elizabeth Bennet before a seminar full of students," says Chris Cram, a former student and Rutgers 1000 founding member. "He has deep feelings on just about every subject—literature, history, philosophy, music, film."

His opinions, and the strength with which he voices them, can be overwhelming. And at least one of his colleagues, who asked not to be identified, says he worried Dowling went too far in molding impressionable young minds. Some of his former students look back at Rutgers 1000 and see a group that assembled around the cult of Dowling's personality.

"It's half that and half just hating jocks and frat boys," says Sean Murphy, one of the student founders of Rutgers 1000 a decade ago. "Dowling was very charismatic. And when you're 19, it's fun to go against the grain and raise your middle finger to the vast majority of your fellow students and the administration. But looking back on it, I have to be honest, what we were proposing wasn't very realistic."

As an expert on 17th- and 18th-century English literature, Dowling has little use for realism. In his world the battle against the evils of commercialized college athletics is an epic poem—Milton would, naturally, be the author—in which Dowling, the much-maligned champion, will ultimately prevail. He sees himself as a lonely guardian of public education against those who would subvert its higher aims in the name of winning bowl games.

"Not everyone can get into Dartmouth or Harvard. You're getting kids who are just that smart who come to Rutgers. And those kids deserve an education too. That's why I'm in this fight," he says. "If people really need to watch football on the weekends, they can go to a Giants game. They don't need to prostitute colleges and universities for the sake of entertainment."

Dowling extends this philosophy to his own alma mater, with which he admits to having a complicated relationship. His disdain for Dartmouth's Animal House culture led him to sever all ties with the College for more than 20 years. He briefly reestablished contact during President James O. Freedman's tenure but has since decided that under President James Wright the school is still not safe for lonely cello players. He keeps a wary eye on the College's sports programs.

"It worries me the Ivy League has been sucked into the vortex of commercialized college sports," Dowling says. "There are no scholarships, so it's been minimized, like the virus used to make a vaccine. But the illness is still there."

He has openly opined against the Ivy Leagues system of athletic set-asides, the system by which each coach submits a ranked list of prospects to the admissions department. He has called for an end to recruiting "hired specialists who are only there because of physical skills." And perhaps someday he'll take his epic quest to the Ivy League. For now, there is a battle to be fought closer to home.

"I think it's a winnable fight. I still do," Dowling says. "Even if it isn't winnable, tilting at windmills is very good for the circulation at my age."

When I was an undergraduate at Dartmouth we had two undefeated football seasons and three Ivy League championships in my four years. I went to a lot of games—Dartmouth was all male, and football weekends were an occasion to date girls from women's colleges like Wellesley and Smith—and I supported the team as staunchly as anyone else in the student body.

But here's the thing. When you were watching an Ivy football game in the 1960s there was always what I now think of as an organic relationship between the players down on the field and the students in the stands. They were us, so to speak, a bit bigger and more coordinated maybe and possessing certain physical skills we didn't have, but other than that just kids who lived down the hall from us in the dorm or who sat next to us in a history seminar or who you'd run into in the library stacks when you had a paper due for the same class.

It's true that those teams didn't play very good football. I remember that during one of the two seasons when Dartmouth went undefeated we got a little cocky about how well the team was doing. That season had come down to a final game against Princeton, also undefeated that year, and Princeton had been featured on the cover of SportsIllustrated. Their captain made the fatal mistake of looking past Dartmouth to football immortality. Unforgivably, he remarked to the SI reporter that, because the Ivy League doesn't allow postseason competition in football, the Princeton team would "never really know how good they were."

This did not sit well with the Dartmouth football players or with the undergraduates. Although finals were coming up and few could really spare the time, a bunch of us took the train down to Princeton to see the final game. The father of one of our classmates, a Dartmouth alumnus, had used his seniority to buy a block of tickets, and we sat as a group in the midst of a crowd of older alumni. Palmer Stadium, the grand old structure that has since been demolished and replaced by a smaller modern stadium, was packed.

Dartmouth defeated Princeton that day, a very satisfying victory over an opponent that had been unwary enough to display a bit of hubris on the eve of the final contest. But I've never forgotten the moment at which, when the game was winding down and it was clear that Dartmouth was going to win, an alum sitting behind us, dressed in fall tweeds, gray-haired and distinguished looking, leaned forward and said gently, "It's all right to celebrate, fellows. But don't carry it too far. You do realize, don't you, that a good Texas high school team could beat either of these teams by two touchdowns?"

As it happened, never having been very far out of New England, I didn't realize that. I do now. Still, the point seems to me unimportant in any larger scheme of things. My tendency is to ask precisely why college football shouldn't be played on an amateur, even sometimes on an outright amateurish, level. If it's real, after all, the teams are made up of college kids, young men who want to go on to do other things in their lives than play football.

The contrast between our situation then and that of undergraduates at institutions like Nebraska and Tennessee and Kentucky and Virginia Tech today couldn't be more dramatic. At those schools the students who go to the stadium or who sit in the seats in the basketball arena have no more authentic relationship to the players on the floor than people who buy tickets to see the Jacksonville Jaguars or the Memphis Grizzlies do to the players on those teams.

Reprinted with permission from Confessions of a Spoilsport by William Dowling (Penn StatePress, 2007).

Mad Professor "As Rutgers' rise toward Tostitos Bowl celebrity continues," Dowling says, "the percentage of bright and intellectually engaged students on campus is steadily shrinking."

"Ait Organic Relationship1' In this passage from his book, William Dowling reflects on his undergraduate days at Dartmouth, which coincided with some outstanding Big Green football teams.

BRAD PARKS is a staff writer for the Newark, New Jersey, Star-Ledger.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Numbers Game

March | April 2008 By LAUREN ZERANSKI ’02 -

Feature

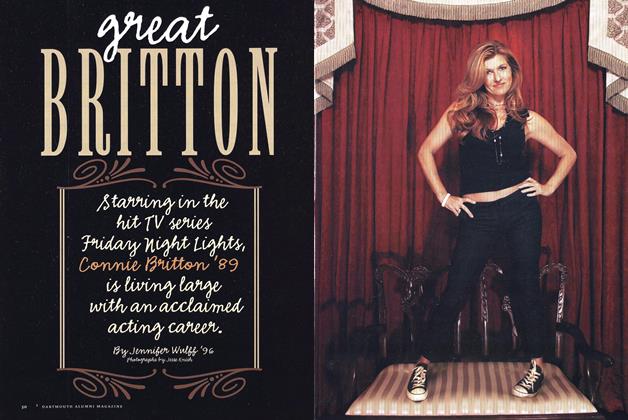

FeatureGreat Britton

March | April 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Interview

Interview“The Timing is Right”

March | April 2008 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

March | April 2008 By Ronald M. Green -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLiving Room Learning

March | April 2008 By Jane Varner Malhotra '90 -

HISTORY

HISTORYDéjà Vu All Over Again

March | April 2008 By Marilyn Tobias

Brad Parks '96

-

Article

ArticleWaking the Dead

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Brad Parks '96 -

Article

ArticleSwitching To Softball

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Brad Parks '96 -

Article

ArticleLandlocked Women Skippers Find Smooth Sailing

September 1995 By Brad Parks '96 -

Sports

SportsMaking all the Right Moves

Sept/Oct 2000 By Brad Parks '96 -

Article

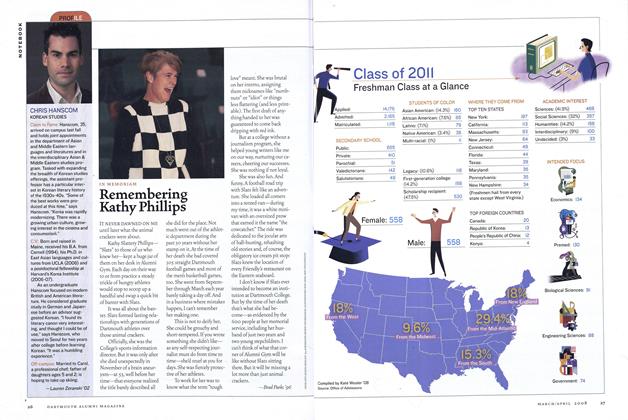

ArticleRemembering Kathy Phillips

Mar/Apr 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

Feature

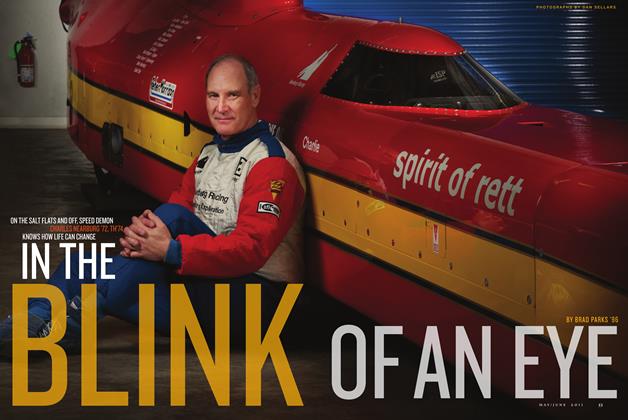

FeatureIn the Blink of an Eye

May/June 2011 By BRAD PARKS '96

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

JUNE • 1986 -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIs the Indian Symbol a Right or an Opportunity?

OCTOBER 1988 By George B. Harris III '50 -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62 -

Feature

FeatureClassnotes

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By LIBRARY COLLEGE DARTMOUTH -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

MARCH 1978 By Shelby Grantham