Scholarship is sometimes as dependent on luck in the field as on hours of research in a library, and scholarly inquiry sometimes proceeds by spurts, following a series of chance observations, much as a detective investigation might. Professor Vincent Malmstrom's interest in the geographic settings of Central American archeological sites was sparked by accident, and his unorthodox conclusions about the origins of Mesoamerican Indian cultures were fed by a fortunate series of happenstance discoveries. "Although my original involvement in this field was what you might call accidental," Malmstrom explained recently, "I soon had a hunch about where the evidence was leading. I didn't go into the field with preconceived notions, but the findings encouraged a certain mind-set so that I began to have ideas of what to look for."

Malmstrom, a geographer whose specialty had been Scandinavian studies, (happened to be leading a Middlebury College foreign study program in Central America in 1973 when, on a visit to the ruins of an Indian city, he began to speculate on a possible relationship between the astronomical alignment of some of the structures, the position of the sun, and the 260-day sacred calendar used by the Mayans. Scholars had long been aware that the 260-day cycle had guided the Mayans' daily rituals and that it possessed both religious and astronomical importance, but no one had a good theory about its origins. Malmstrom wondered why 260 had been chosen as the number of days in the ritual year and where the calendar had its beginnings.

He noticed that it would be easy for people living in the narrow band between the latitudes of 15°N and 14°42'N to measure the 260-day interval between transits of the sun at its zenith simply by counting the number of days between the times an upright stake or pillar cast no shadow. Within the geographical region just south of the 15th parallel, he also observed, the sun reaches its zenith on August 13, which happened to be the month and day on which the Mayan calendar commenced — the day they said the world began.

Excited by these discoveries, Malmstrom, who came to Dartmouth in 1976, checked to find out if any important archeological sites were located in the area specified by his developing theory. He was delighted to learn that the ancient city of Copan, the Mayans' principal astronomical center, located in the highlands near the Gulf coast of present-day Honduras, was situated in the right latitude. Furthermore, in light of Copàn's astronomical significance, a number of scholars had already hypothesized that the calendar might have originated there.

Upon further study and reflection, however, Malmstrom began to have doubts. Although the calendar had been shown to be in operation as early as 400 B.C., Copàn was not founded until 495 A.D. In addition, many of the tropical animals for which days on the calendar are named are not found in the highlands around Copan. Armed with this evidence that the calendar most likely came from somewhere else, Malmstrom looked for another, older, site in the lowlands and found that the only place meeting his geographical and historical criteria was the large pre-Columbian ceremonial center of Izapa, on the Pacific coastal plain of southern Mexico, just north of the Guatemalan border. Professionals in the field, whose scholarship was based on the assumption that the Indian civilization originated on the Gulf coast, were annoyed, Malmstrom said during a conversation this summer, with his claim that Izapa was very likely the "cradle of Olmec civilization, the mother culture of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica."

"Because of Copan's pre-eminence in astronomy, there is a strong temptation to ascribe the origins of the tzolkin [calendar] to this place — a temptation which I feel impelled to resist on historical grounds," he wrote in an article for Science magazine. "On the contrary, rather than arguing in favor of Copàn as the birthplace of the calendar round [cycle], I would propose just the reverse, namely, that the calendar round was responsible for the founding of Copàn."

Returning to Central America almost every year since his first chance discovery in 1973, Malmstrom has found further evidence to buttress his theory, including a consistent alignment of archeological sites at Izapa and at dozens of other locations to a compass bearing of 285 degrees, the precise spot on the horizon where the sun sets on August 13, the mythological day of creation. The sites are also in alignment with prominent mountains and with the rising or setting sun at the summer or winter solstice. "Thus, it was possible for a priest standing atop the main pyramid at Izapa not only to calibrate accurately the length of the sacred 260-day almanac," Malmstrom explained in a recent paper, "but also, by counting the number of days which elapsed between consecutive sunrises over the highest mountain in Central America, the true length of the tropical year as well." He even employed a computer to run time backward in both the sacred and secular calendars and found that the secular 365-day calendar most likely started June 21, 1323 8.C., and that the sacred calendar goes back to August 13, 1358 8.C., dates in accord with other archeological evidence.

In an article about the development of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican calendar systems, published in 1978 in the Journalfor the History of Astronomy, Malmstrom proposed the following chronology: First, the sacred 260-day calendar, based on the transit of the vertical sun, originated at Izapa in 1358 B.C.A short time later, during the period 1323-1320 B.C., a 365-day calendar based on the number of days between consecutive sunrises over Central America's highest mountain, Tajumulco, came into use. Third, calibration of the true length of the solar year, accomplished by observing intervals between consecutive sunrises over mountains, spread with the use of the calendar throughout Central America and helped determine where ceremonial centers were to be built.

Malmstrom has another kind of evidence, also discovered by accident, for Izapa's cultural primacy: magnetic artifacts. (The trouble with finding magnets, according to Malmstrom, is that they pose as many questions as they answer.) In 1975, while Malmstrom was investigating the alignments of structures at Izapa, a student inquired about the possible significance of the orientation of a series of sculptures. A compass was used to take bearings from the figures, and Malmstrom was astounded to find that a carving depicting a turtle's head, which could date back as far as 1500 B.C., possessed a strong magnetic field, concentrated in its snout. This chance discovery was particularly surprising because the Chinese had been assumed to be the discoverers of magnetism - the first evidence of their knowledge dates from about the time of Christ - and because only one small, crudely made ancient magnet had previously been found in Central America. Malmstrom had stumbled upon the world's earliest known magnetic artifact in a totally unexpected location. No magnetic properties were found in other sculptures at the site, although additional carvings of turtles were present. Malmstrom suggests that the sea-faring Izapans might have associated the turtle's uncanny navigational ability with magnetism.

Most recently, while on a research trip to Guatemala last winter, Malmstrom and Paul Dunn '81 discovered the magnetic properties of a whole series of sculptures — again by accident. The sculptures, representations of human figures and heads carved on five- to ten-ton basaltic boulders, six or seven feet in diameter, had been unearthed in the late 1940s at a site called Monte Alto and put on display in the town of La Democracia. Malmstrom, Dunn, and a writer for Sports Illustrated were visiting the town's museum when the reporter asked if the sculptures, called "fat boys," were magnetic. Malmstrom was sure they weren't - the Indians' association of magnetism with turtles seemed reasonable, but it seemed unlikely they would attribute its qualities to humans.

Upon checking, however, the sculptures were found to be of even more interest than the turtles. They were older (dating from about 2000 B.C.), there were seven of them, and the patterns of their magnetic fields were strikingly repetitive — too similar to be merely coincidental. The four heads have north magnetic poles located in their right temples and south poles below their right ears. Two of the three bodies have both north and south magnetic poles located near their navels within ten centimeters of each other. The north pole of the third body is located in the back of its neck, but the location of the south pole, which might be in the sculpture's buried base, couldn't be determined. At another location, a carving showing two seated men has the north pole at the navels of both and the south pole between the figures.

Malmstrom has no firm theories about how the Olmecs discovered the magnetic properties of basalt. Olmec civilization used no iron, and there is no real evidence they had other magnets, lodestones, or compasses to determine magnetism. "One can only assume they must have had a magnet of some sort," Malmstrom says. In a recent report, "Pre-Columbian Magnetic Sculptures in Western Guatemala," Malmstrom and Dunn confess that "the authors are at a loss to explain either the patterns of occurrence in the heads and bodies of the 'fat boy' sculptures or any possible significance they might have had." They do, however, add weight to theories about the importance of Izapa and the Pacific coast origins of Olmec civilization.

One of the more intriguing possibilities suggested by Malmstrom's research is that the Olmecs might have borrowed some of their knowledge from another culture. The question is, which one? The most likely neighbors resided across the Pacific. Malmstrom has pointed out that other researchers have noticed "striking evidence of similarities between the Olmecs and the Shang-dynasty Chinese." For example, both cultures made a practice of placing a jade pebble in the mouth of the dead before burial, and both employed similar styles of scrollwork on art objects. Malmstrom concluded a recent paper by stating, "In any event, it would appear that Izapa served as a major center of cultural innovation in Mesoamerica, whether as a trans-Pacific bridgehead or as a hearth in its own right." Possible sources of influence on the Olmecs, and the diffusion patterns of Olmec culture, are some of the topics Malmstrom will be investigating during his next visits to Central America. He is about to finish a book summarizing and explaining his research to date.

Responding to the question of why a geographer is so interested in archeology and anthropology, Malmstrom, who paired a college major in geography with minors in geology and anthropology, said he saw the study of geography as "a bridge between the physical and social sciences." He said he felt challenged, particularly after the skepticism with which his original report on the calendar was received by scholars, to continue and further substantiate his findings. "I'm not a 'digger,' " he pointed out. "I'm not interested in looking at bits of broken pottery. I'm looking at the big picture of a culture and its diffusion. That's what a geographer does."

On the origins of the Mesoamerican "mother culture"

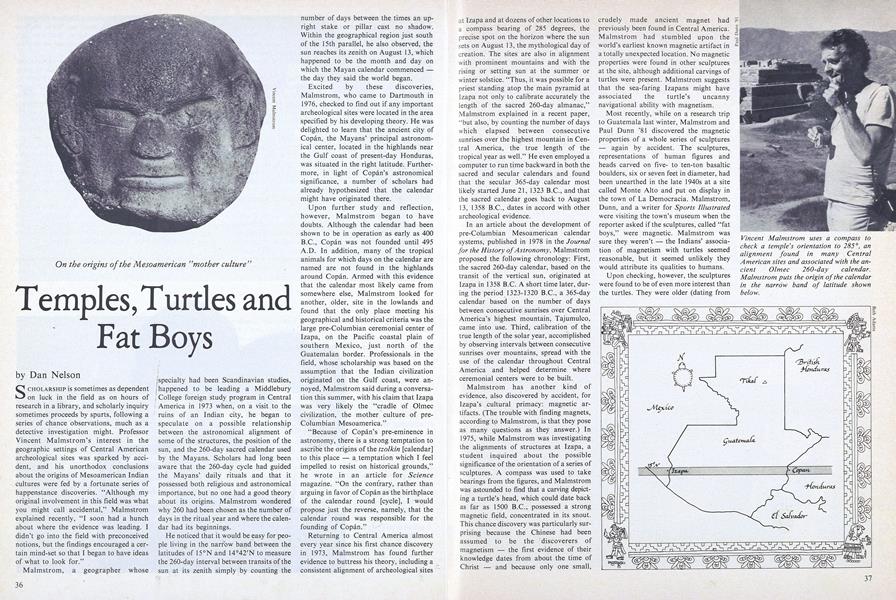

Vincent Malmstrom uses a compass tocheck a temple's orientation to 285°, analignment found in many CentralAmerican sites and associated with the ancient Olmec 260-day calendar.Malmstrom puts the origin of the calendarin the narrow band of latitude shownbelow.

Paul Dunn '81 inspects one of the 4,000-year-old Guatemalan "fat boys" whosemysterious magnetic qualities were first discovered by Dunn and Malmstrom this year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUps and Downs in the Big Leagues

September 1979 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

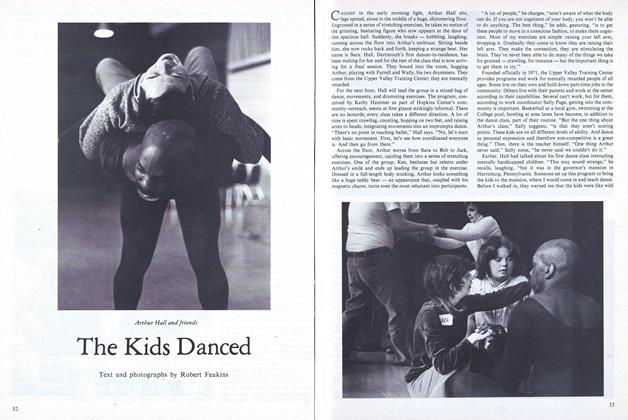

FeatureThe Kids Danced

September 1979 By Robert Feakins -

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

September 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE, Fred Alpert '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

September 1979 By WILLIAM B. CATER JR. -

Article

ArticleCarving Out Spaces

September 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

MARCH 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureDrinking

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Cover Story

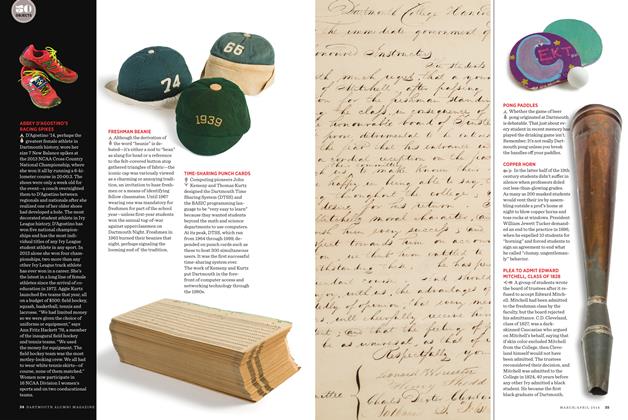

Cover StoryTIME-SHARING PUNCH CARDS

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

JULY 1969 By KENNETH IRA PAUL '69 -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60