FDR’s Secret Weapon

Basil O’Connor, class of 1912, was not only an intimate of Roosevelt but also a driving force in the eradication of the disease that paralyzed the president.

May/June 2008 C.J. Hughes ’92Basil O’Connor, class of 1912, was not only an intimate of Roosevelt but also a driving force in the eradication of the disease that paralyzed the president.

May/June 2008 C.J. Hughes ’92BASIL O'CONNOR, CLASS OF 1912, WAS NOT ONLY AN INTIMATE OF ROOSEVELT BUT ALSO A DRIVING FORCE IN THE ERADICATION OF THE DISEASE THAT PARALYZED THE PRESIDENT.

ALONG THE PERIMETER OF THE ROOSEVELT WARM Springs Institute for Rehabilitation in Warm Springs, Georgia, a paved path winds through a patch of loblolly pines, a place for people in wheelchairs to savor the countryside.

It's named the Basil O'Connor Memorial Nature Trail, but judging by the sign—small, subtle, tucked behind bushesthis O'Connor person couldn't have been all that important.

Like the sign on the wheelchair trail, however, O'Connor is almost hidden from the eyes of history, despite the fact that he was a major force behind the eradication of polio in this country and, by extension, the world. Indeed, in contrast to the 350,000 cases worldwide as recently as 1998, there were just 1,278 cases of the disease recorded in 2007, according to the Global Polio Eradication-Initiative, with the lion's share in Nigeria and India. (While polio has been detected in a longer list of countries—Afghanistan, Niger, Pakistan, Chad, Somalia, Myanmar, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Nepal among them—health experts are optimistic that polio can be wiped out within a decade.)

Dr. Jonas Salk, of course, gets the credit for developing a vaccine in 1952, though O'Connor drummed up the tens of millions of dollars needed to pay for it. He did so using an innovative approach—the March of Dimes, which now focuses on the prevention of birth defects—to have the American public kick in for something that would benefit the general population. O'Connor used Hollywood celebrities and massmarketing tactics to get people excited, prefiguring how the government deals with public-health crises today, whether triggered by diseases or natural disasters.

"Next to FDR, O'Connor is the most important figure in the story about the fight against polio," says David B. Woolner, executive director of the Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute in Hyde Park, New York. "Roosevelt put full trust in O'Connor, more than in many in his inner circle," he says. "O'Connor was a great organizer, a superb fundraiser and the kind of person who saw things through to their completion."

He also cut a striking pose. With slicked-back hair and rimless glasses, a pocket square tucked in his jacket and a lapel garnished with a fresh red or white carnation, he calls to mind young Humphrey Bogart.

His dapper appearance, however, belied a humble background. Born January 8,1892, Daniel Basil O'Connor—he dropped the first name in his professional life—grew up in working-class Taunton, Massachusetts, in a family of five children whose Irish father was an ironworker, according to Jane Hennity, director of the Old Colony Historical Society in Taunton.

At Dartmouth he was a competitive debater and member of the College orchestra, also playing violin in bands at school dances to help pay tuition. A resident of Reed Hall, he later joined Sigma Phi Epsilon, living there when it was located on South Main Street. O'Connor majored in political science, appropriately enough, and studied Latin and biology. O'Connor also picked up the nickname Doc," owing to the way he scribbled his signature, with a looping "D," "O" and "C." Because O'Connor wasn't athletic, "Doc" also stuck as a joke, so the story goes, since it was also the nickname of the football coach, John O'Connor.

After graduating at age 20, O'Connor headed off to Harvard Law School, where he graduated in 1915 at age 23. A series of high powered corporate law jobs in Boston and New York City followed. It was in the latter place that he first met Roosevelt through mutual friends in Democratic political circles, most likely in 1920, though details of their introduction are unclear.

At the time their fates might have seemed headed in opposite directions. O'Connor was a rising legal star with Wall Street connections, his commanding list of oil-industry clients catapulting him into a world of wealth and prestige. Roosevelt, on the other hand, was licking his wounds after losing his bid for the vice presidency in the 1920 presidential election as James Cox's running mate.

A more serious blow would come FDR's way in July 1921, when, after an impromptu political stop at a Washington, D.C.-area Boy Scout camp, he came down with an illness that kept him bedridden for weeks at the family compound on an island off the coast of Maine. Eventually he was diagnosed with polio, a diagnosis called into question in recent years with speculation Roosevelt may have instead suffered from Guillain-Barre syndrome. Either way, he basically became a paraplegic, though he thought it was temporary.

"It was such a big shock to the family because he was a very active man," says Woolner, the Roosevelt Institutes director. "But he never gave up the hope that he would regain the use of his legs," despite the difficulty of standing without a cane.

Polio was still shrouded in mystery, even though doctors had identified it decades before, after an outbreak in 1843. At the time it was known as infantile paralysis, since it affected mostly younger people. After the turn of the century, however, the disease began afflicting adults, too. A 1916 outbreak caused 27,363 polio cases and 7,179 deaths, yet there was no agreement about how it was transmitted. Doctors would later learn the poliomyelitis virus is transmitted from stool to mouth, usually by people who don't wash their hands, and that once ingested the virus heads through the bloodstream to the brain stem. There, in many cases, it destroys the nerve cells that cause muscles to contract. Paralysis results—as localized as an elbow or as massive as the entire body below the neck.

Despite his own paralysis Roosevelt still aspired to a public office, and O'Connor—a man of "unusual attainment and of delightful personality," according to a letter of recommendation written by Roosevelt in January 1926 to the New York Yacht Club—could help FDR get there by putting him in touch with the New York City powerbrokers who could later support his White House bid.

In 1924 Roosevelt began talking with O'Connor about creating a law firm, and O'Connor, though already running one of his own, was happy to oblige; the Roosevelt name, he thought, would open doors to a whole new universe of clients. In 1925 the two opened the firm of Roosevelt and O'Connor, located at 120 Broadway, a couple blocks from Wall Street.

If O'Connor got into the partnership for the money, he quickly became sidetracked by Roosevelt's ceaseless quest to walk again.

After reading news accounts of Louis Joseph, a young polio victim who claimed that regular exercise in the water bubbling out of the ground in Warm Springs, Georgia, helped him use his legs again, Roosevelt rushed to the Meriwether Inn and Resort Hotel near Columbus, a faded retreat where the springs were pooled. He, too, thought the 88-degree waters containing a rich mix of iron, sulfur, magnesium, lime and sodium, among other ingredients, had special properties.

The actual medicinal value of the waters is debatable, doctors have said, but their buoyancy created the sensation of walking and anything that got polio victims to exercise to keep their remaining muscles from atrophying was good. Plus, the minerals in the water leave a silky, unique feeling on the skin, as visitors to Warm Springs can attest today. Whatever the case, Roosevelt believed the Meriwether property, with a little work, could become a world-class, polio-focused hospital.

Ignoring the advice of his family and possibly O'Connor, who thought it would be a foolhardy investment, according to magazine articles from the time, Roosevelt in 1926 plunked down $200,000 (which would be roughly $2.1 million today) to buy the resort along with some contiguous parcels of land.

Almost as soon as FDR got there, however, political opportunity came knocking. In 1928 O'Connor was asked by Roosevelt to take over the facility while he ran for governor of New York.

The inn, falling apart, needed major renovations, but there was almost no budget. O'Connor tapped colleagues and friends for the cash, convincing Edsel Ford, for example, to pony up $25,000 for a revamped pool, a Roman-style pavilion with spacious changing rooms and a glass roof. (The roof is gone today and the pools are drained, but the pavilion houses a small museum.) During the next few years O'Connor would also build medical facilities and dormitories, brick buildings with columns and breezeways framing courtyards on a campus that even to this day rivals those of many small colleges. By 1932 the property would also include the humble complex of cottages that would become Roosevelt's hideaway from Washington, known as the "Little White House," where he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1945.

"I'm not sure that this place would have ever made it in those first few years without continued charity," says Michael Shadix, the hospital's librarian. "O'Connor was wonderful at getting people to buy into it." He had a knack for networking, especially considering that the nation was reeling from the Depression. For example, O'Connor brought in Keith Morgan, a top insurance salesman, and Carl Byoir, a public relations executive, to brainstorm ways to raise money for the hospital.

Byoir's Eureka moment was an idea to throw a series of nationwide birthday parties for Roosevelt—essentially, non-election year grassroots fundraisers. The "birthday balls" began on January 30, 1934. Six thousand of them were held that first year—on Indian reservations, on ski slopes and in union halls—with the theme "We Can Dance So Others May Walk." To the surprise of their organizers, that first year the events raised more than $1 million, according to David Oshinsky's Polio: An American Story.

O'Connor dreamed up other tactics around the same time. He asked advertising executives to design posters featuring smiling kids in leg braces alongside catchy slogans about walking again. Consumer advertising, typically used to sell cars or soda, was being used to fight a disease. Next, in an era before celebrities and causes celebres were inevitably linked, he turned to well-known entertainers such as Ginger Rogers, Bing Crosby and Jack Benny to speak up for the cause of treating polio. It was Eddie Cantor, a vaudeville, radio and silent-movie star, who actually came up with the name "March of Dimes," a play on the popular March ofTime newsreels, for the centerpiece of O'Connor's campaign.

In 1938, as that year's fundraising drive was ramping up, Cantor suggested that people send 10-cent pieces right to the White House. And they did—2,680,000 dimes in all—many bulging out of envelopes, according to Oshinsky. (It's also why Roosevelt's profile ended up on the dime.)

Before the 1930s fundraising for diseases such as tuberculosis was usually the provenance of a few wealthy individuals. O'Connor reasoned he could reach the same dollar totals with many small gifts. He turned out to be right.

Money for polio treatment took a back seat to national security concerns during World War 11, however. During the war O'Connor had to wear another hat, when in 1944 Roosevelt asked him to head up the American Red Cross. O'Connor chaired the organization for five years, mobilizing millions of volunteers to roll bandages, pack sweaters and raise troop morale.

In a move that was classic O'Connor—asking citizens to chip in what government would not—he also launched the first national civilian blood drive. Though the program had existed during the war for soldiers, he kept it going afterwards, asking people to put a few pints in a blood bank to help civilians out. In 1948 the first collection site opened in Rochester, New York, and expanded nationally from there.

Departing by train from Washington on March 29, 1945, O'Connor accompanied Roosevelt on what would be the presidents final trip to Warm Springs. When the president died there on April 12 the polio cause was robbed of its most high-profile champion, but O'Connor hardly paused. By the 19505, with the focus shifting from treating polio to hoping to eradicate it, he had recruited a new medical team to find a cure. Adding urgency to their mission was the fact that the number of polio cases was skyrocketing. In 1952 there were a record 57,879 polio cases, with 3,145 resulting in death. Tens of thousands of victims were likely crippled.

Racing against the clock Dr. Jonas Salk developed a killed-virus vaccine in 1952. After Salk tested it on his wife and the three Salk sons, among others, O'Connor agreed in 1953 to let field trials go ahead, involving more than 1.8 million children and costing the Red Cross more than $7.5 million. Betting the vaccine would work, O'Connor quickly spent another $9 million so six drug companies could start making the vaccine. Any delay meant more lost lives.

On April 12,1955—coincidentally, the 10th anniversary of Roosevelt's death—O'Connorwon that bet when Salkand his team announced at the University of Michigan that their vaccine was almost 90 percent effective. "The vaccine works. It is safe, effective and potent," said Dr. Thomas Francis Jr. "[It] may slow down what had become a double-time march of disease to a snail's pace."

It did. By 1960, after a massive and sustained inoculation campaign, there were just 2,525 paralytic cases in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control. By 1965 that number had dropped to 61.

A campaign begun at a past-its-prime Southern resort almost three decades before, slowed by an economic crisis, a world war and presidential death, had nevertheless triumphed.

On balance O'Connor's commitment to the cause of polio victims seems to have been bom out of a profound sense of loyalty to Roosevelt, a man who invited O'Connor to sit in at Cabinet meetings though he never held a Cabinet position.

Ironically, though, the political turned personal for O'Connor in 1950, when his daughter Bettyann discovered she had contracted polio. Like other victims before her, Bettyann convalesced in Warm Springs, returning there periodically for checkups until she died of uterine cancer in 1961 at the age of 41.

This blow came just six years after the death of Bettyann's mother, the former Elvira Miller, whom O'Connor had married in 1918. In 1957 he would marry Hazel Royall, whom he met when she was working as a physical therapist in Warm Springs.

According to accounts of people who knew him in Warm Springs, O'Connor had a steely, no-nonsense reserve and could be fussy to a fault about cedar closets for his clothes and a daily copy of The New York Times driven in from Atlanta. The pain of losing a daughter, however, seemed to soften him, according to Cathy Culver Hively, O'Connors granddaughter.

To honor Bettyann, O'Connor installed Westminster chimes at Snug Harbor, his sprawling 27-acre estate in Westhampton, New York, and had them play carillons at noon and 6 p.m. every day: "He wasn't a snuggly person; just not that way, but it showed his tender side," says Hively, who also recalls her grandfather reprimanding a maid for putting margarine on the table, because it was "lower class" than butter.

Patients at the hospital, too, recall a businesslike quality in O'Connor that could seem imperious. When he decided to close the outdoor pools at Warm Springs in the 19405, after new indoor ones had been built, it didn't sit well with some local children who were used to cooling off in them, according to Suzanne Pike, who came to the hospital in 1932 for treatment for her club feet and has never really left. Even though Pike was sad to see the public pools go, she realizes O'Connor was "thinking of the patients and their welfare, and that's what the president wanted him to do," she says. "Mr. Roosevelt had high expectations and he knew that Basil O'Connor would take care of the place."

In later years O'Connor seemed to hint at that type of unflappable dedication—an almost quaint notion, perhaps, in today's more patronage-weighted political climate—even after his mentor had passed away. Speaking in 1962 at his 50th Dartmouth reunion, O'Connor said he believed what he had accomplished was as much a credit to the American people as to himself. "The temptation to remain disengaged from the problems of the times is great today," he said. "The issues are ambiguous and confused. It takes more than courage to be committed. It also takes intelligence and hard work to understand and judge each problem."

In 1972 O'Connor, a longtime smoker—he was often photographed clutching a 14-karat gold cigarette holder monogrammed with "BOC"—died of atherosclerosis while attending a March of Dimes meeting in Arizona and was buried in Westhampton, New York. The gravestone, with a smooth black circle perched on a granite slab, has an inscription that reads, "Only as he lives in both the private and the public life can a man today take hold of his own destiny."

More personal comments came in a eulogy delivered on March 13,1972, in New York City, when Dr. Salk memorialized him with a poem. "Being a leader and a winner, he could neither follow nor lose. He acted soft and tough—but not sweet and hard. Born sensitive, he knew above all how to endure," Salk wrote. "He was rare—so rare there were none to match him, nor are there any to replace him."

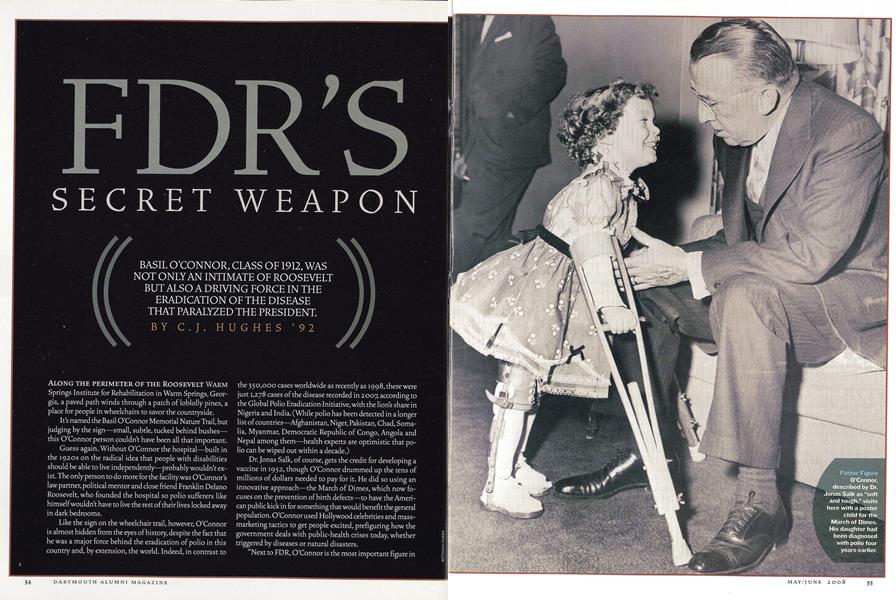

Father Figure O'Connor,described by Dr.Jonas Salk as "softand tough," visitshere with a posterchild for theMarch of Dimes. His daughter hadbeen diagnosedwith polio fouryears earlier.

Face of the Foundation O'Connor was a frequent—and ardent- speaker on the need to eliminate polio. He remained dedicated to the cause even beyond FDR's death and worked closely with polio vaccine developer Dr. Jonas Salk (far left).

O'CONNOR ASKED ADVERTISING EXECUTIVES TO DESIGN POSTERS FEATURING SMILING KIDS IN BRACES ALONGSIDE CATCHY SLOGANS ABOUT WALKING AGAIN. CONSUMER ADVERTISING, TYPICALLY USED TO SELL CARS OR SODA, WAS BEING USED TO FIGHT A DISEASE.

C.J. HUGHES is afreelance journalist who lives in Manhattan. His work hasappeared in The New York Times, New York, Time Out New York and Architectural Record.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

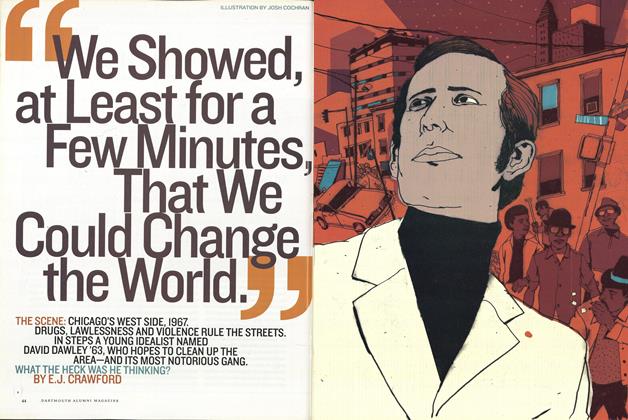

Cover Story“We Could Change the World”

May | June 2008 By E.J. CRAWFORD -

Feature

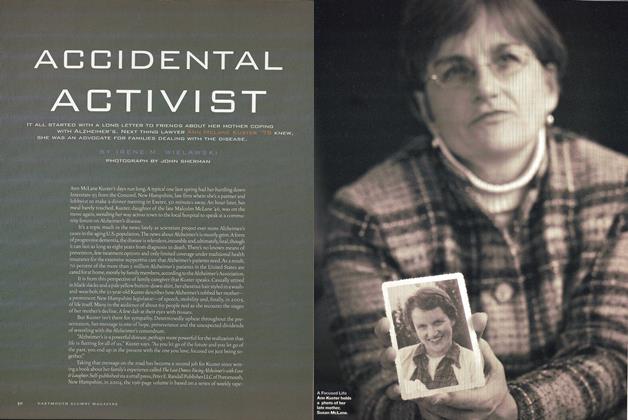

FeatureAccidental Activist

May | June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

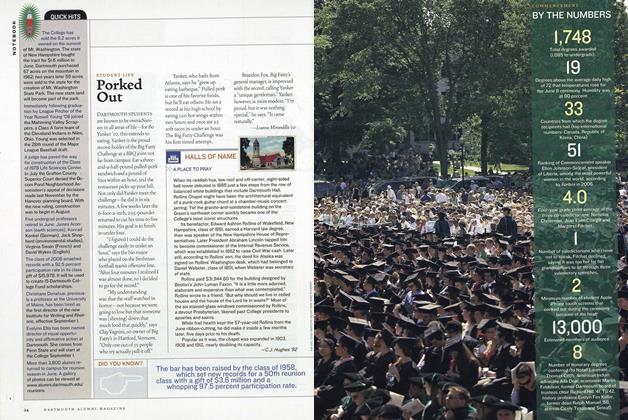

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2008 By Kit Wilson '89 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May | June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGetting the Picture

May | June 2008 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

C.J. Hughes ’92

-

Article

ArticleHALLS OF NAME

Sept/Oct 2008 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Article

ArticleHALLS OF NAME

Jan/Feb 2009 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Cover Story

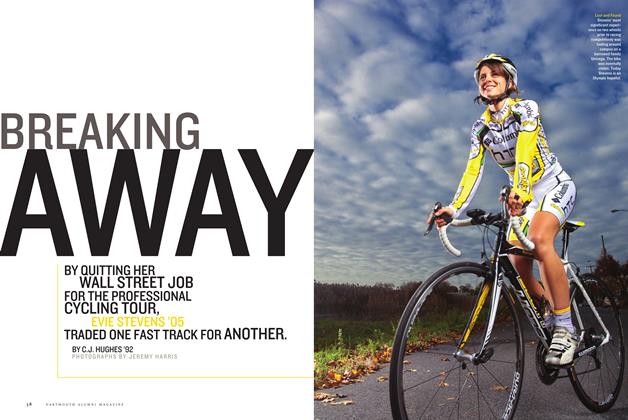

Cover StoryBreaking Away

Jan/Feb 2011 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

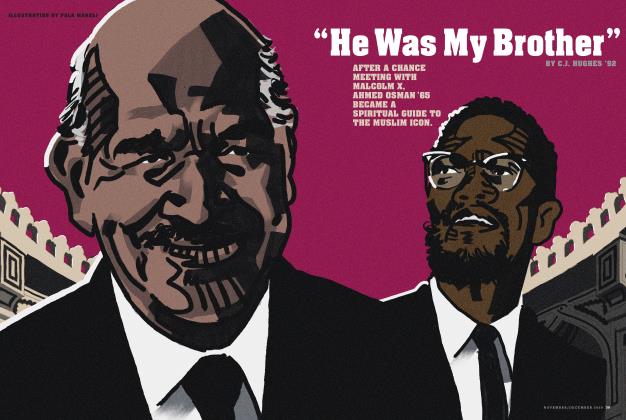

Feature“He Was My Brother”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSRock and Beyond

MARCH/APRIL 2023 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

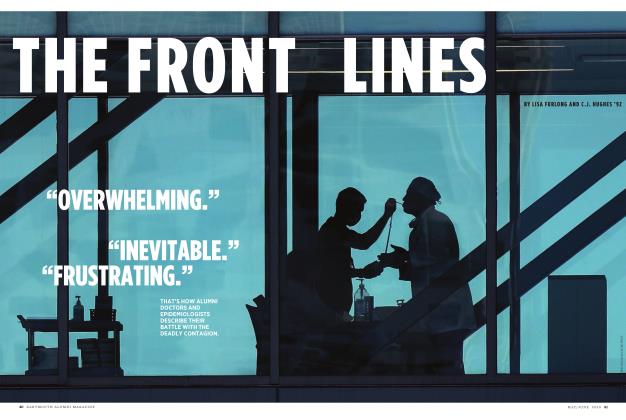

FeatureThe Front Lines

MAY | JUNE 2020 By LISA FURLONG, C.J. Hughes ’92

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSun, Smoke, and Scholars

June 1987 -

Cover Story

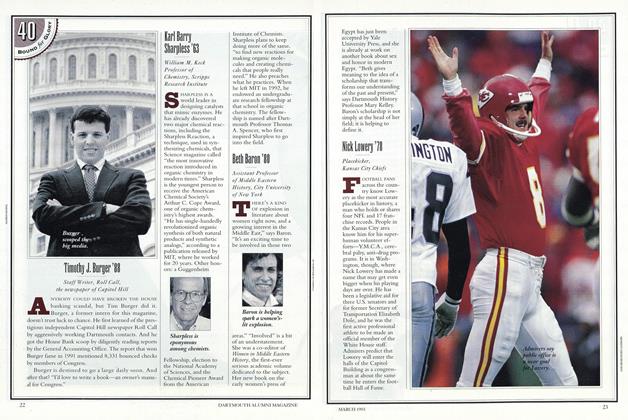

Cover StoryKarl Barry Sharpless '63

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureChronicling the DOC

DECEMBER 1984 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

FeatureAn Atlantic Community

July 1961 By JEAN MONNET -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Bridge Pretty Darn Far

MARCH 1995 By John Collier '72, Th'77 -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS