Accidental Activist

It all started with a long letter to friends about her mother coping with Alzheimer’s. Next thing lawyer Ann McLane Kuster ’78 knew, she was an advocate for families dealing with the disease.

May/June 2008 Irene M. WielawskiIt all started with a long letter to friends about her mother coping with Alzheimer’s. Next thing lawyer Ann McLane Kuster ’78 knew, she was an advocate for families dealing with the disease.

May/June 2008 Irene M. WielawskiIT ALL STARTED WITH A LONG LETTER TO FRIENDS ABOUT HER MOTHER COPINGWITH ALZHEIMER'S. NEXT THING LAWYER KNEW, ANN MCLANE KUSTER '78 KNEW, SHE WAS AN ADVOCATE FOR FAMILIES DEALING WITH THE DISEASE.

Ann McLane Kuster's days run long. A typical one last spring had her hurtling down Interstate 93 from the Concord, New Hampshire, law firm where she's a partner and lobbyist to make a dinner meeting in Exeter, 50 minutes away. An hour later, her meal barely touched, Kuster, daughter of the late Malcolm McLane '46, was on the move again, wending her way across town to the local hospital to speak at a community forum on Alzheimers-disease.

It's a topic much in the news lately as scientists project ever more Alzheimer's cases in the aging U.S. population. The news about Alzheimer's is mostly grim. A form of progressive dementia, the disease is relentless, incurable and, ultimately, fatal, though it can last as long as eight years from diagnosis to death. There's no known means of prevention, few treatment options and only limited coverage under traditional health insurance for the extensive supportive care that Alzheimer's patients need. As a result, 70 percent of the more than 5 million Alzheimer's patients in the United States are cared for at home, mostly by family members, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

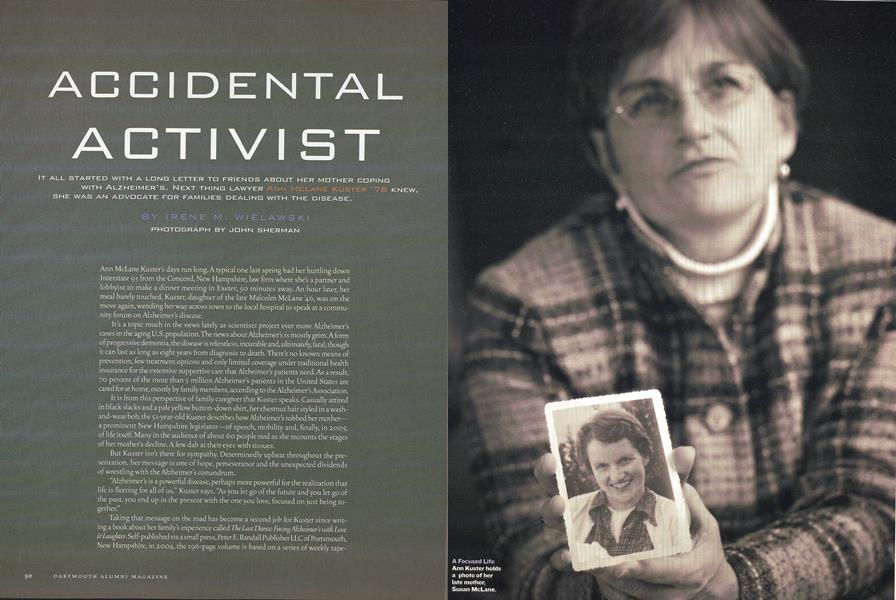

It is from this perspective of family caregiver that Kuster speaks. Casually attired in black slacks and a pale yellow button-down shirt, her chestnut hair styled in a wash-and-wear bob, the 51-year-old Kuster describes how Alzheimer's robbed her mother a prominent New Hampshire legislator—of speech, mobility and, finally, in 2005, of life itself. Many in the audience of about 60 people nod as she recounts the stages of her mother's decline. A few dab at their eyes with tissues.

But Kuster isn t there for sympathy. Determinedly upbeat throughout the presentation, her message is one of hope, perseverance and the unexpected dividends of wrestling with the Alzheimer's conundrum.

"Alzheimer's is a powerful disease, perhaps more powerful for the realization that life is fleeting for all of us, Kuster says. "As you let go of the future and you let go of the past, you end up in the present with the one you love, focused on just being together."

Taking that message on the road has become a second job for Kuster since writing a book about her family's experience called The last Dance: FacingAhheimer's with Love& Laughter. Self-published via a small press, Peter E. Randall Publisher LLC of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 2004, the 196-page volume is based on a series of weekly tape- recorded interviews Kuster undertook to capture her mother's life story before Alzheimer's obliterated the memories. "For me, the challenge was to figure out how to make lemonade out of lemons and learn to focus on what was left, not what was lost," she says.

The book chronicles Susan McLane's life and final years as well as how the extended McLane family coped, offering a window into the emotional complexity of the Alzheimer's journey for patients and loved ones. Alzheimer's specialists have lauded the book. One of them, Dr. Robert B. Santulli, assistant professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School, recommends it for medical professionals who work with Alzheimer's patients and their families.

Since publication of The Last Dance Kuster has been telling her mother's story—and her own—in dozens of public forums such as the one last spring at Exeter Hospital. She's given radio and newspaper interviews and appeared in nursing homes, church halls and senior centers throughout New England, staying afterwards to sell copies of the book. (Proceeds go to aging and Alzheimer's disease support programs.) It's never a brisk transaction. With the check invariably comes a story about a husband or wife or parent or sibling lost to the fog of Alzheimer's. Kuster listens, nods and murmurs her understanding. More often than not the conversation ends in a hug. It's well after 10 on these nights before Kuster gets home to her husband and teenage sons Zach and Travis. (Zach is now a Dartmouth freshman.)

How all this came about—and continues three years after her mothers death—still amazes Kuster. "This started out as a very long Christmas letter the year she was diagnosed, 2001," Kuster explains. We had about 300 copies made at a copy shop and sent it out to family and friends to let them know what was going on with us. At that early stage we never thought wed put this out as a book and share it with strangers."

It was Susan McLane's public stature that dictated the mailing list. A New Hampshire state legislator and political dealmaker for 25 years, McLane had championed hospice care, abortion rights, tax reform, environmental protection and mental health parity. Her influence was such that the June 1994 issue of New Hampshire Magazine featured her on the cover under the title "1994's Most Powerful Woman." A passionate birder, McLane was also a stalwart of New Hampshire Audubon, serving on its board and helping to raise money. The society's new nature center in Concord is named for her.

In writing the "Christmas letter," a 150-page narrative, Kuster interspersed her mothers reminiscences with her own account of the diagnosis and impact of the illness. Alzheimer's typically goes undiagnosed for several years because early symptoms—short-term memory loss, confusion over names or words, difficulty following conversations—can easily be attributed to old age. In detailing these mental lapses Kuster was honoring her mothers wish to be forthright. "You could say it was her last cause," Kuster says. By talking about her Alzheimer's without embarrassment or apology, McLane hoped to promote public awareness and lessen its stigma.

And so the Christmas letter went off to the post office—a done deal, Kuster thought, until letters in reply began to pour in, some from well beyond New Hampshire's borders. "We got about 100 of them, and it was the anecdotes they told about Alzheimer's in their own families that made me really consider going further," Kuster says. "People were passing our Christmas letter around and we were getting letters from people who never even knew her!"

Among the letters were quite a few from people like Kustermiddle-age daughters or sons with careers, spouses, children and, suddenly, an ailing parent. It was the first inkling for Kuster that her family's experience of Alzheimer's was part of a larger intergenerational tableau. This is what she explores in her book, amidst a plethora of anecdotes and reminiscences to illustrate how the McLanes and Kusters celebrated, supported and finally let go of the woman who had been their center of family life for half a century. Picking up where the 2001 Christmas letter ended, the book flashes back to Susan McLanes early life while chronicling the mounting toll of Alzheimer's. Dartmouth is no small part of that story, since she was the daughter of Lloyd K. "Pudge" Neidlinger, dean of the College from 1934 to 1952.

Susan and her two sisters were a common sight on the campus of the 19405, riding bikes across the Green, climbing trees, shooting pool at SAE house and skiing circles around the College boys. With her identical twin, Sally, Susan was a contender for the U.S. Olympic team, but only Sally made it in 1948 because by then Susan was already a wife and mother, having dropped out of Mount Holyoke to marry and move to England with Dartmouth ski team captain and Rhodes scholar Malcolm McLane '46.

From England the McLanes went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, so Malcolm could attend Harvard Law School, then to Concord, New Hampshire, where he joined an influential law firm. Susan stayed home to raise their five children. Because the supermarket was across the street from the State House, and because she was free during school days, she watched the legislative action from the visitors' balcony. What she saw piqued her interest.

In telling her mother's story, Kuster also tells her own, including memories that aren't always in sync. There seems to have been a snap point for her mother when Annie, the youngest of the five McLane children, was 12. While her mother recalls in the book that Annie came home from the first day of seventh grade to tell her, Mother, get a life!"—an anecdote Susan used over the years to explain why she decided to run for the legislature—Kuster has no recollection of having said it. "My mother," she writes in the book, "may have heard the words she wanted to hear." For Kuster, the stronger memory is of navigating adolescence with a mother too busy to share the ups and downs of her last teenager. In her work as a lobbyist Kuster now walks the same legislative halls as her mother, but she's made a deliberate choice not to run for public office while her children are at home. "I am very aware of the cost of that to family life," she says.

It was through repeated encounters with such divergent and emotionally charged memories that Kuster says she began to come to terms with issues in her family relationships that she hadn't thought about in years. Because it targets memory and mental competence, reducing even the most impressive—or oppressive, as the case may be—parent to a childlike and helpless state, role reversal inevitably takes place over the prolonged course of the illness. Kuster found she had to lay much of the past to rest in order to deal effectively and compassionately with the present. Gently in the book, and more pointedly in conversation and at public appearances, Kuster explores the divide between her generation, raised in the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, and their World War 11-era parents who today account for most of the nation's Alzheimer's patients.

"We are the boomer generation, anti-authority in our youth and all about rejecting tradition," Kuster says. "We saw ourselves as infallible, and in some cases stayed estranged from our parents for a long time." As a teenager Kuster experienced older brothers and sisters in various stages of rebellion and breaking away. "I was the youngest in my family, still at home trying to deal with parents who were dealing with that reaction," she says. Kuster ended up being the only one of her siblings to follow the McLane family tradition to Dartmouth. A member of Dartmouth's third coeducational class, she hid the fact she had applied from her grandfather, the legendary dean. "He was opposed to coeducation," Kuster explains.

Fast forward to 2000 as Kuster, busy lawyer, wife and mother, found herself pulled back into the McLane family thicket by the mystery of her mother's worsening memory lapses. Her father was obviously worried, and Kuster suggested consulting a doctor. Chapter two in The Last Dance begins with a description of this medical visit—and Kuster s first step into a new kind of relationship with her parents that "turned out to be closer than I ever anticipated."

"Sitting in the doctors waiting room with my mother for the first time in 30 years, I was suddenly aware of the role reversal," Kuster writes. "In the doctor's office she sat up on the examining table as I watched from a chair by the desk."

Kuster wasn't sure how to handle her new role. Even with siblings nearby and willing to help—an older sister and brother live in New Hampshire and another sister lives in Vermont—someone had to take primary responsibility for assisting Malcolm (who died in February) with Susans care "My mother raised me by example," she says. "I spent my childhood campaigning with her and putting on events with her and understanding the importance of making a difference in the world." Helping her father care for her mother was Kuster's way of setting an example of family unity for her sons.

Ten days before Susan McLane died in the spring of 2005 she lost her ability to swallow, a complication of Alzheimer's in the final stages. She had previously made clear to her family that she did not want to be kept alive artificially. Kuster, her father, siblings and other relatives took turns at the bedside so McLane would not die alone. It was all they could think of to do, but Kuster acknowledges terrible strain as the days went by, wondering if they were doing the right thing. She was overwhelmed by how Alzheimer's had ravaged her mother, "a world class skier who couldn't walk, a state senator and public advocate who couldn't speak." It took Herculean resolve in those final days, Kuster says, tp hold onto the good memories she'd shared publicly in her book.

Kuster's message since her mothers death has evolved, partly in response to feedback from her readers and listeners. The same turn of mind that led her to ponder the intergenerational tensions laid bare by Alzheimer's now has her searching for a way to tailor her positive message to caregivers with fewer resources than the McLanes have. The impetus, Kuster says, was a call she got while discussing senting too rosy a picture of Alzheimer's disease and its impact on families. Indeed, researchers have documented serious health consequences among people caring for later-stage Alzheimer's patients at home, including depression, sleep and anxiety disorders, social withdrawal and significant physical deterioration.

Kuster now takes pains to acknowledge her family's advantages, including an unusually cheerful and accepting patient. The McLanes' financial resources enabled them to pay for professional respite services when needed and, in Susan McLanes last year, nursing home and hospice care. McLane never exhibited the two most difficult symptoms of Alzheimer's disease: personality changes that can result in verbal and physical abuse of caregivers, and a tendency to wander away from home. Early on McLane lost speech and mobility, which made her care at home much easier.

"It's exponential the different ways this disease can be experienced," Kuster says. "My book is our family's experience—actually, let me correct that—it's my experience. It's not necessarily how my siblings would write the book."

But as her life hurtles forward, as busy as any baby boomers with work, family responsibilities and a household to run, Kuster holds tight to the most enduring lesson of her mothers illness: the importance of living in the moment.

"I can still remember the feeling entering my mother's life at the nursing home," she says. "We used to say entering her time zone,' with Oprah on the television, the staff working all around, meals being served, life going on one day at a time. We watched Ronald Reagan's funeral procession and her face finally lit up when she recognized Barbara Bush and Hillary Clinton from her past. She was aware of all the pomp and circumstance, but she had no idea what it was all about. She just knew that they had been her friends once a long time ago."

A Focused Life Ann Kuster holdsa photo of herlate mother,Susan McLane.

KUSTER EXPLORES THE DIVIDE BETWEEN HER GENERATION,TURBULENT 1960S AND 1970S,PARENTS WHO ACCOUNT FOR MOST OF THE NATION'S RAISED IN THE AND THEIR WORLD WAR II-ERA ALZHEIMER'S PATIENTS.

IRENE M. WIELAWSKI is a regular contributor to DAM. A health carejournalist, she writes from her home in Pound Ridge, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover Story“We Could Change the World”

May | June 2008 By E.J. CRAWFORD -

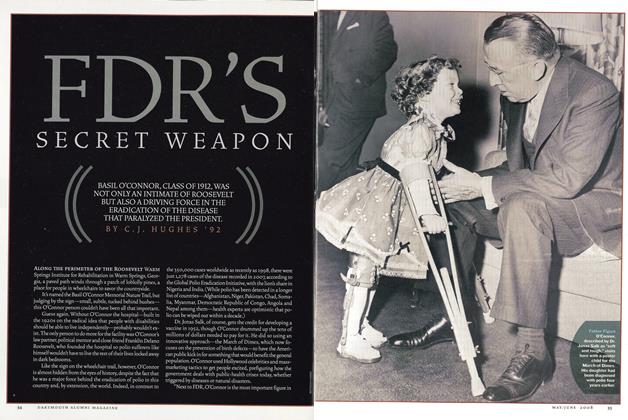

Feature

FeatureFDR’s Secret Weapon

May | June 2008 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2008 By Kit Wilson '89 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May | June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGetting the Picture

May | June 2008 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

Irene M. Wielawski

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

Mar/Apr 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

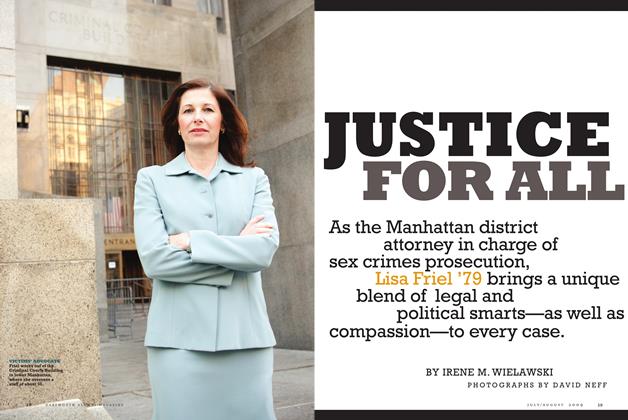

Cover StoryJustice for All

July/Aug 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

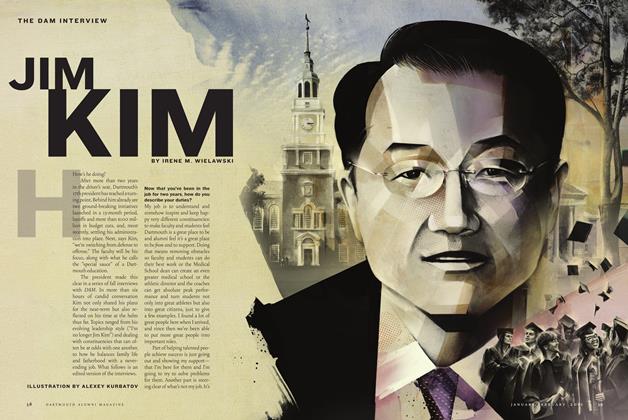

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJim Kim

Jan/Feb 2012 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

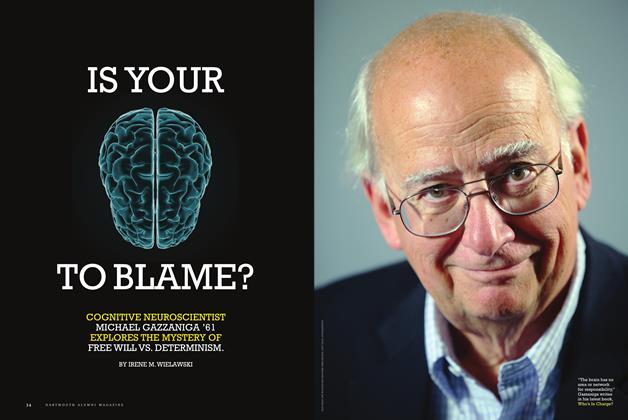

Cover StoryIs Your Brain to Blame?

Nov - Dec By Irene M. Wielawski -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBThe Future of Cancer

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By Irene M. Wielawski -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYLifesaver

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By Irene M. Wielawski

Features

-

Feature

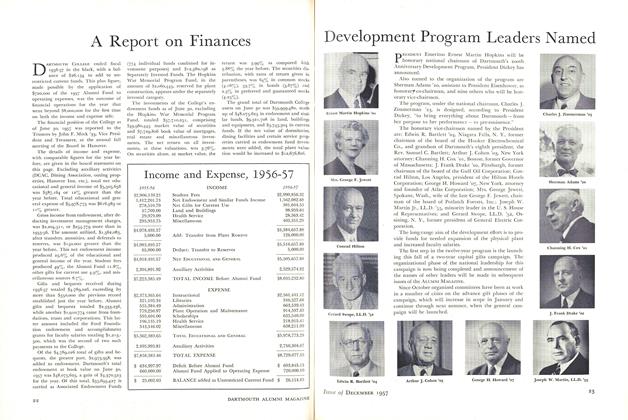

FeatureDevelopment Program Leaders Named

December 1957 -

Feature

Feature"Your Business Here..."

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

JUNE 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Unknown History

JANUARY 2000 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

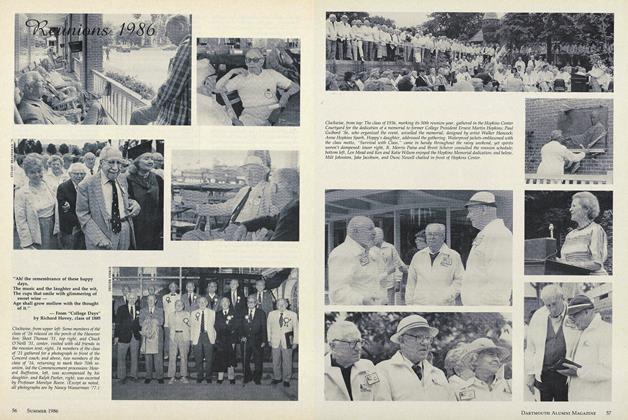

Feature

FeatureReunions 1986

JUNE • 1986 By Richard Hovey