Getting the Picture

Working as a production assistant for television and movies has given one recent grad an appreciation of life on the streets.

May/June 2008 Andrew Mulligan ’05Working as a production assistant for television and movies has given one recent grad an appreciation of life on the streets.

May/June 2008 Andrew Mulligan ’05Working as a production assistant for television and movies has given one recent grad an appreciation of life on the streets.

WHEN I SHOWED UP IN HANOVER in the fall of 20011 hadn't a clue what kind of career I wanted. It was an uncertainty I'm sure I shared with many of my fellow '05s. There were, of course, those few who knew from day one that they wanted to be doctors or lawyers or hedge fund managers or teachers and I envied their resolve. But, I figured, four years was plenty of time to narrow it down.

When by senior year I was still at sea regarding what to do with my future, panic set in. Many of my friends had already received acceptance letters from graduate schools. Others were mulling over competing offers from various banks and investment firms. The guy who lived across the hall at my fraternity house had not only secured a premier financial job, he had the multi-thousand-dollar signing bonus to prove it.

I had to think of something. So, one day, probably while watching a DVD with my friend Viraj Patel '05,1 decided that I was going to give the movie business a shot. "I've always loved film," I thought to myself. "What if I could get away with making a career out of it?" Soon after, I called my mom and told her that all I ever wanted to do in life was make movies. This was what I had to do.

My first job after graduation, thanks to some help from a screenwriter friend of my parents, was as an assistant in the production office of a network sitcom that was being filmed at a studio in Long Island City, Queens.

At first the woman who was to be my boss was skeptical of my employability. She mistrusted my Ivy League credentials (I found out later that she had a degree from Brown). Despite her trepidation, I got the job.

My main responsibilities as a production assistant (P.A.) were taking out the garbage, ordering lunch, answering the phone, shuttling co-workers to and from the subway and dishing pizza and cookies onto plates for the live studio audience during tapings. For working an average of 60 hours a week, I was paid S6O0—no overtime, no health insurance. I had arrived.

Though I sometimes chafed at the things I was asked to do, I was happy with my job. I liked the people and I loved the atmosphere at the studio. Most of all, I loved telling people what I did for a living. They were almost invariably intrigued. "Did you get to meet so-and-so?" they would ask. "What's she like in real life?" I would shamelessly satisfy peoples craving for inside info by repeating tidbits Id heard about this star's weird allergy or that ones lecherous tendencies. I wouldn't be surprised to find out that all the rumors in the history of Hollywood were started by some grandstanding P.A.

In March of 2006, with my sitcoms season at an end, I began to look for my next gig. Though I had enjoyed working in the office for my first job, I wanted to be closer to the action. This meant getting a job on set. Spring in the television business is pilot season, when studios shoot the first episode of shows they are thinking about putting on their fall schedules. Dozens of pilots are shot, but only a few end up being picked up for a full season. Utilizing the contacts I had made in my first few months I landed a job on the set of a much-hyped pilot being produced by a major studio.

I arrived for my first day at 4 a.m. My "call time" was 4:30 but I didn't want to risk being late. I soon saw the prudence of my thinking. At 4:35 one of the assistant directors starting calling the P.A.s who hadn't arrived yet. His message was succinct: "Don't bother showing up. You're fired."

I performed many different duties during my stint as a freelance set P.A., but I spent the majority of my time on "lockup." Locking up basically amounts to standing on a street corner and telling people they can't walk down the sidewalk because there is a movie or TV show being filmed. Sometimes people are accommodating but most of the time they are hostile. I never met a P.A. who got through a day on lockup without a few exchanges involving profanity or threats of violence.

I've heard many people say that shooting on the street is like going to war, and although now may not be the best time to be making such flip comparisons, there are some similarities. Both, for instance, involve long stretches of idleness broken up by furious spurts of activity. The industry has also appropriated some military lingo. When shooting out on the street, pedestrians who cross into the shot are called "bogeys." Those who respect the boundaries of the set are known as "civilians" or "noncombatants." The battle to complete the days scheduled work is often made to seem like a life-or- death struggle upon which the fate of nations depends.

In the spring of 2006 I worked a few days on a big-budget movie that needed some extra hands. We were shooting a complicated dream sequence in which an actress goes up on a wire and "flies" over a deserted street. Since deserted streets are hard to come by in Manhattan, it was up to the dozen or so P.A.s to keep pedestrians out while the camera was rolling. I was assigned to a corner at the back end of the shot.

After a couple hours of standing around doing nothing I got my first bit of action. Three black SUVs started rolling down my street from the west, toward the shot. This was puzzling because car traffic was supposed to be diverted at the other end of the block by the NYPD. The SUVs stopped a few yards before the corner and when the occupants emerged I quickly realized why the cops had let them through. I made no effort to impede their progress as they passed through my lockup and into the shot.

Almost immediately, my walkie- talkie crackled to life: "Mulligan! Get those people the hell out of the shot! Your lockup is like Swiss cheese!" Itwas one of the assistant directors and he was obviously too far down the street to fully appreciate the situation. "Um," I said back into my headset, "it's Mayor Bloomberg and the president of the production company." I didn't feel the need to mention the phalanx of security surrounding the men. There was a brief silence, followed by the assistant director coming back with: "Well, can you ask them politely to get the hell out of the shot?" I told him that I wasn't getting paid enough to execute such a request and then pretended to have a dead battery in my walkie-talkie.

One of the coolest things about being involved in the making of a movie or television show is seeing just how many uniquely talented people are necessary to take a project from script to screen. Some of the hardest working and most talented professionals in the industry are those whose names flit across the screen after everyone has already left the theater. Where's the Oscar for the craft service personnel who work tirelessly to ensure that there are enough enchiladas to go around at 4 a.m.? How about a Golden Globe for the production supervisor who tracks down a replacement camera lens in the middle of the night in rural Connecticut? Another Emmy could surely be cast for the electrician who spends a sub-zero night atop a 40-foot lift making minute adjustments to a light for a mercurial director of photography.

For me, sometimes it was enough just to be there. When the going got tough I thought about the movies that had inspired me through the years and the people who had undoubtedly braved similar or worse hardships to bring those to the screen. Their efforts had paid off for me—perhaps mine would for someone else.

One of my toughest moments took place deep in the heart of Manhattans Chinatown. The last shot of the day, known as "the martini," was up, which meant that the unusually grueling day was finally coming to an end. I was on a lockup at camera left, keeping the sidewalk clear so the movies heroine could enjoy a twilight kiss with her on-screen beau. A Chinese woman selling vegetables from a sidewalk cart started to read me the riot act. I don't speak Mandarin and she didn't speak English, but I could tell she thought my lockup was depriving her of business. I wanted to tell her that if she could just bear with us for a few minutes it would all be over, but as I was powerless to explain this with hand signals I chose to simply ignore her. No sooner had I turned around to continue diverting people than I felt something cold and wet hit me hard in the back of the head. I turned around and saw her standing there, looking daggers at me and screaming while brandishing her weapon of choice. Was this really happening? Had I actually been clubbed with a bunch of celery? I managed a smile by recalling the final scene of myall-time favorite movie. "Forget it," I thought to myself. "It's Chinatown." a

Was this really happening? Had I actually been clubbed with a bunch of celery?

ANDREW MULLIGAN, a former DAM intern, is working on a novel in Brooklyn, NewYork.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

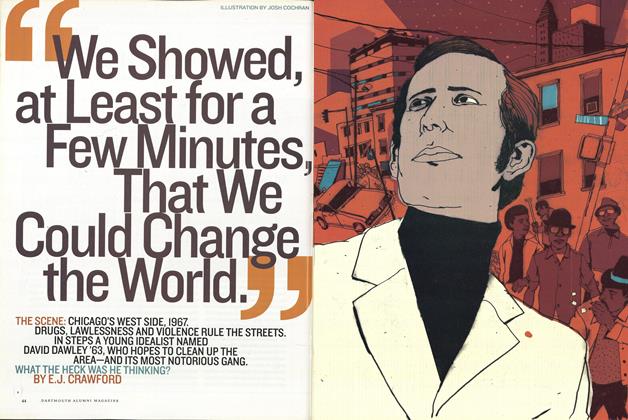

Cover Story“We Could Change the World”

May | June 2008 By E.J. CRAWFORD -

Feature

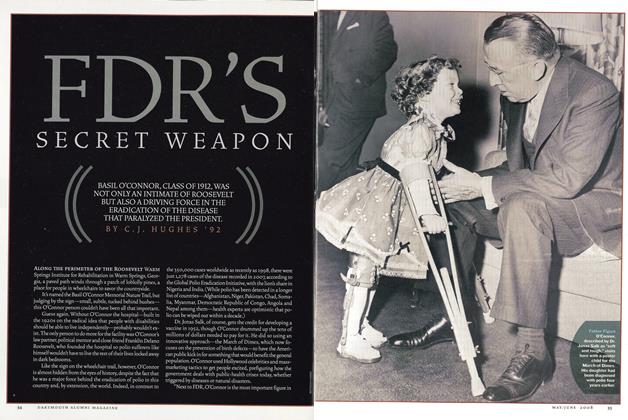

FeatureFDR’s Secret Weapon

May | June 2008 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

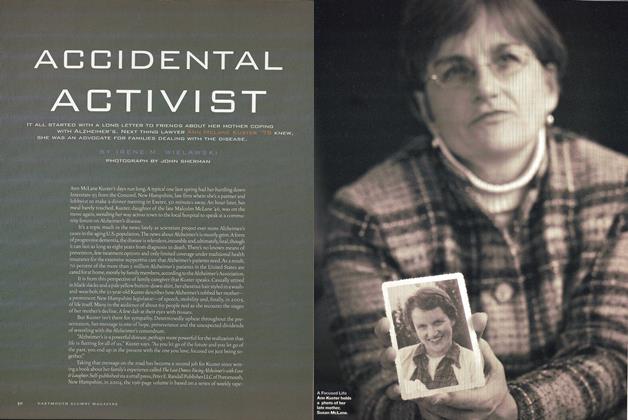

FeatureAccidental Activist

May | June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2008 By Kit Wilson '89 -

Tribute

TributeThe “Prone Ranger”

May | June 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08

Andrew Mulligan ’05

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

MAY 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Devil and Dan Club

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jim Collings ’84 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

Sept/Oct 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYFrom Town to Gown

July/August 2007 By John W. Norton ’50 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYReel Oddity

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By TOM ROPELEWSKI