“Examine Assumptions”

Professor Bernie Gert talks about philosophy as a calling—and spending five decades at Dartmouth.

Mar/Apr 2009 Leanne Mirandilla ’10Professor Bernie Gert talks about philosophy as a calling—and spending five decades at Dartmouth.

Mar/Apr 2009 Leanne Mirandilla ’10Professor Bernie Gert talks about philosophy as a calling—and spending five decades at Dartmouth.

PHILOSOPHY PROFESSOR BERNIE GERT HAS HAD A LONG AND FRUITFUL CAREER, having made significant contributions to his primary field of ethics—specifically, medical ethics. His 1998 book Morality: Its Nature and justification is considered a staple for any student of ethics, and he is well known for his The Moral Rules: A New RationalFoundation for Morality (1966). Gert has taught at Dartmouth since 1959 and helped start Dartmouth's Ethics Institute. He has seen his children Joshua and Heather embark on philosophical careers of their own—and marry philosophers. Gert, the Stone Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy, plans to retire from teaching after spring term. Here he reflects on his career.

How has the field of philosophy changed in the last 50 years?

It's become more technical, more specialized. As the field becomes more crowded, people have to carve out little niches. Philosophers are now trying to take into account more of what's done in some of the empirical sciences such as evolution and human nature and cognitive science and neuroscience. Things that explain why we think the way we do. Philosophers used to do a lot just by thinking. Now they're taking advantage of the research that's being done in other fields.

How have Dartmouth studentschanged through the years?

The average SATs of students have gone up, but there have always been good students here. Philosophy has always attracted veiy good students. In the old days, before the scientists took over, I think one-third of the Phi Beta Kappas were philosophy majors. My experience with Dartmouth students has always been very positive, and I've always based my writing upon my teaching. If I couldn't persuade the students, then I thought there was something wrong with my argument. So I would keep changing year after year until I finally got a way of presenting that was clear and convincing enough that the students would accept it.

Why have you stayed here so long?

After being here for two or three years my wife and I were not happy with Hanover, because it was so small that everybody knew everybody else. Then our daughter was bom, and we decided there could not be a better place to raise children. So we decided that we wouldn't even dream of leaving until our children went off to college. By then we had already been here for 20, 25 years and were pretty used to the place.

Dartmouth is a wonderful place to teach and provides a lot of resources for you. There's no question that Dartmouth has the best undergraduate philosophy department in the country. It compares to some graduate departments. Undergraduates are, for me, a lot of fun to teach because they don't get caught up in the jargon and the details. They're interested in the larger picture. When I taught the very same book—the first version of my Moral Rules—in the spring term at Dartmouth, then in the fall term at Johns Hopkins when I was a visitor there, it was just so interesting to see the different reactions of the Dartmouth students and the graduate students at Hopkins. The grad students were interested in the little details, and the Dartmouth students were interested in the more general issues. My writing is less technical than many other philosophers', partly because I'm teaching undergraduates.

How does philosophy prepare people for careers?

Many of our majors go on to law or medical school. Philosophy is extraordinarily good preparation for law school, as you can see from our majors' GRE results. I think philosophy majors have the highest acceptance rate into medical school—even higher than the biologists, chemists, etcetera. If the premeds are confident enough to major in philosophy, they're very good. Also, the medical schools want people to be able to think about life issues.

Is philosophy more challenging than other academic fields?

It's not accidental that philosophers can do so well in a wide variety of reasoning. Philosophy classes are the only classes I know where you regularly have students read things you know are wrong. What you do is present material and say, "Tell me what's wrong with it." Students are supposed to examine assumptions. That's what philosophers do. And there's philosophy of everything. Philosophy of law, philosophy of medicine, philosophy of religion, philosophy of history—there is no subject matter that isn't part of philosophy.

What topics do you discuss withother philosophers?

Though everybody agrees on 95 percent of moral issues, nobody talks about those cases. But how about abortion and euthanasia? That's what people talk about. When you stop to think about the areas on which we disagree, they're a very small percentage. But they're the ones we talk about all the time, so you get this feeling that all moral issues are controversial. And there's no reason to think that there's a single right answer for those controversial issues. When you say there's universal morality, people think you're dogmatic and intolerant of differences, but that's not true. Nobody thinks you should be tolerant of people who lie and cheat and steal and kill. I am more aware that there's an object of universal morality.

When you go to philosophy meetings, which I've done in places like Australia and Israel and Argentina, the philosophers are all the same—in their tweedy coats and elbow pads. And they all look the same—not quite with it.

What is it like to have your childrenworking in your field?

Whenever I tell people about that the standard response is, "Wow, you must have some Thanksgiving dinners!" I didn't encourage my children to go into philosophy because the job market was so, so bad. But they could see how much fun it was, that I really enjoyed it. I kept trying to dissuade my daughter from doing philosophy, but she said, "Everything else is so boring!" My wife is the one non-professional philosopher. She's the normal person in the family.

What are you working on now?

Two things: a book on [English philosopher] Thomas Hobbes and a book on human nature. I've been working on the book on human nature for about 15 to 20 years. It addresses two of the most important influences on my work on human nature, Freud and Darwin. It's been a challenge.

What else will you be doing once youstop teaching?

A former student [Etta Pisano '79], who is now the vice dean for academic affairs at University of North Carolina Medical School, has had me come in the last few years to introduce more ethics into the medical school. I do some mentoring. I'll probably continue to do that down there. Then I have these books to finally finish up. I may do some occasional work here at the Medical School, in conjunction with the Ethics Institute. For the American Society for Practical Professional Ethics I'm going to be on a panel with an anthropologist about revising their ethics code. I'm also going to be on an American Society for Bioethics and Humanities panel about common morality. I expect I will continue to be invited to do things, so I plan to pretty much continue the career as it has been, except for teaching.

Bernie Gert

"Undergraduates are, for me, a lot of fun to teach because they don't get caught up in the jargon."

LEANNE MlRANDILLA is a DAM internfrom Hong Kong. She is an English major.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

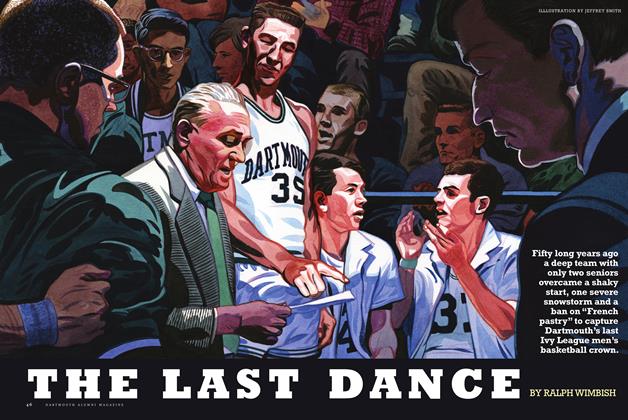

FEATUREThe Last Dance

March | April 2009 By RALPH WIMBISH -

FEATURE

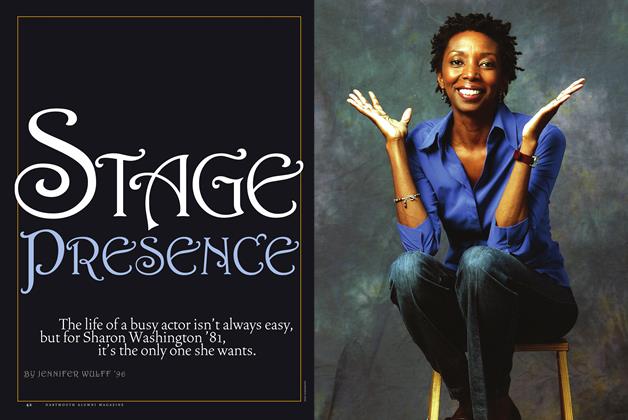

FEATUREStage Presence

March | April 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

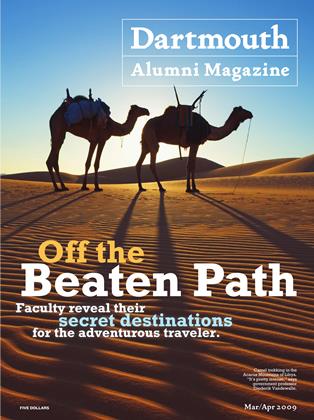

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"It Hasn't Been Commercialized"

March | April 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"See the Beautiful Architecture"

March | April 2009

Leanne Mirandilla ’10

Interviews

-

Interviews

InterviewsLook Who’s Talking

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By Anne Bagamery ’78 -

Interview

Interview“The Timing is Right”

Mar/Apr 2008 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

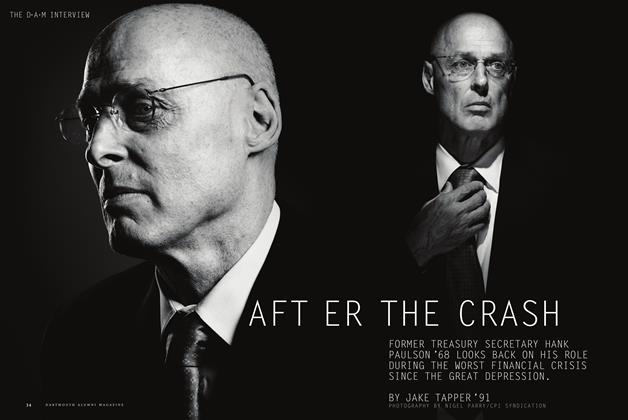

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWAfter the Crash

Mar/Apr 2010 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Interview

InterviewLook Who’s Talking

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Madison Wilson ’21 -

Interview

InterviewMany Happy Returns

Nov/Dec 2000 By Robert James Bauer '82 -

Interview

Interview“An Improbable Opportunity”

July/August 2012 By Sean Plottner