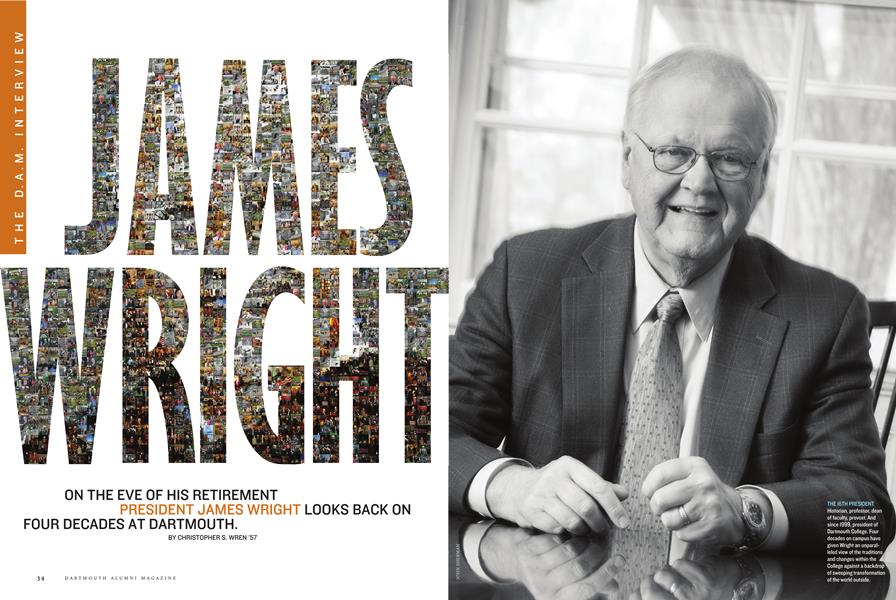

James Wright

On the eve of his retirement President James Wright looks back on four decades at Dartmouth.

May/June 2009 CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57On the eve of his retirement President James Wright looks back on four decades at Dartmouth.

May/June 2009 CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57The 16th president. Historian, professor, dean of faculty, provost. And since 1999, president of Dartmouth College. Four decades on campus have given Wright an unparalleled view of the traditions and changes within the College against a backdrop of sweeping transformation of the world outside.

What has happened to Dartmouth since you arrived 40

years ago?

The Dartmouth I came to in 1969 was a campus of 3,200 men. Probably 90 percent were white. There were maybe 100 international students, but most were from Canada or Western europe. The College operated on a conventional nine-month calendar. It had a handful of off-campus programs. most were language study programs in Western europe. The medical School was still a two-year school; Tuck and Thayer were schools in which a significant proportion were Dartmouth undergraduates who had gone on to get an advanced degree. There were some small graduate programs in arts and sciences. It was a time when the campus was in a state of transition and tension in terms of civil rights and women’s rights. There had been the occupation of Parkhurst hall and students protesting the Vietnam War. Yet it was remarkably welcoming. I had never been in new england until I came out to Dartmouth for a job interview.

You’d never been to New England?

No. I came out here in October of 1968 for a couple of days and within a week I was offered a job. I came here at $10,000 a year, which then was a lot of money. I was delighted, but I certainly didn’t come here with any idea that I would be staying for 40 years.

My first office over in Reed Hall was so small that if two students came to see me at once we had to move outside, because there was not room for three chairs in the office. I never for a moment imagined being here in President Dickey’s office.

But it was a place where I felt comfortable. People really went out of their way to make other members of the Dartmouth community feel welcome. It was also a place where teaching was an important part of the culture. I loved to teach. I worked so hard preparing my classes and was so apprehensive about it, but I took to the classroom early on. I loved being in the classroom with Dartmouth students.

You came out of high school in Galena, Illinois, and went into the Marines for three years, then you opted to go to college. What motivated you to take the road less traveled?

I grew up in a community where most people did not think about going to college. I assumed that after I graduated from high school I would probably go to work in the mines or the Kraft Foods cheese plant nearby or the John Deere Dubuque Works in Iowa, across the river.

I grew up in a family that was very loving and supportive. I read a lot, but I didn’t think about going on to school. When I was in the Marines I continued to read everything from trashy paperbacks to works of great fiction. I started thinking about college at that time. When I got out of the Marines my ambition was to become a high school history teacher and maybe a football coach. I’d never been a particularly good student. I discovered I was an A student if I worked hard.

There’s no doubt that early experience helped to define my relationship and my expectations for Dartmouth. I was here as Dartmouth became a coeducational community, became larger, more diverse. We went to a year-round calendar. Today the sun never sets on Dartmouth College. There’s someplace in the world always where there are Dartmouth students and faculty studying. I have been privileged to be a part of that expansion and that enrichment. But I’ve always stayed rooted in those things I think have helped to define Dartmouth, which is a sense of community, of inclusiveness and a place for faculty and students to have very special relationships and learn together.

What was it like when women enrolled?

The year I started here women enrolled at Dartmouth for a year in the 12-college exchange program. I had a few women in my history classes. I taught a freshman seminar my first year that would have been all men, but most classes had one or two women.

There was clear support for coeducation on the part of the faculty and students. It was also clear that many alumni were concerned about the consequence for the culture and institution they valued very much. alumni concern about coeducation was not based upon some sort of misogynist redneck resistance. The women who came here in the 1970s finished the sale, because we had a remarkable group. They were tough as nails. They needed to be, unfortunately. They were able, and very quickly adopted Dartmouth as their own. But they were not going to change the fundamental qualities of the institution. That was important.

It was also important that—let’s face it—alumni had as many daughters and granddaughters as they had sons and grandsons. As their daughters and granddaughters came here, they came to have a richer appreciation. Maybe even today some people still wring their hands about losing the old Dartmouth, but I don’t think that’s been a major factor for most alumni.

At what point did diversity on campus begin to broaden?

President John Dickey ’29 started that process. he recognized that if we were going to assume responsibility for the world’s problems as our problems we needed to have more international students. He reached out specifically to some students from Japan in the 1950s. By 1964 he was talking more about race. He talked more about the African-American experience. So he helped to set the table. John Kemeny pressed ahead with that, as has every president since.

Dartmouth is a place that does prepare and empower people to have positions of leadership and responsibility in this country and in the world. If we’re going to do that we have an obligation to make certain we’re providing an environment and opportunities where students can learn from other students.

Was your decision to bring veterans to campus part of further diversifying the student body?

All of us in places of privilege have a responsibility to try to reach out. My work has focused on trying to encourage wounded veterans to think about pursuing their education. We have nine veterans at Dartmouth now and I’m very pleased. But I didn’t set out to say, “okay, how can I make Dartmouth better?” It’s more, “how can I help these people reach their potential?” They have sacrificed and done so much. There’s no doubt they make Dartmouth better. They add a dynamic to a classroom that is quite remarkable.

When you came to teach, computers were primitive.

The whole digital and electronics revolution has had a profound impact. It’s possible to search and sort data in ways that would have taken teams weeks to do 40 years ago. The wonders of computation and data storage and the power and capacity of these machines are incalculable in a very positive sense.

Let’s think, though, about some other consequences. I worry that information is readily available without any sense of accuracy or priority. There’s no filtering process for what appears on some sites that people go to. So it’s crucial to do exactly what a liberal arts education should do in any event, which is to teach our students to use data and sources critically, to try to assess the accuracy of analysis and information. There’s a greater responsibility on us to make certain that part of an education is not simply putting something in a Google search and saying, “I’ve got the answer!”

At Dartmouth learning is part of a collaborative process. When I think of those things that characterize Dartmouth students, it’s a capacity to be part of a team and to work well with one another. one can collaborate in cyberspace, but it’s altogether different than a group sitting around a table and throwing ideas back and forth. I worry about losing some of those tremendous interpersonal skills that define leadership by spending too much time at a keyboard. I sometimes see two students walking down the street together. and as I get closer I realize they’re not talking to each other, but each of them is talking on a cell phone.

John Dickey never had to contend with e-mail or blogs. I don’t know that when Dickey spoke it didn’t have at least some of the qualities of a Moses on the mountain. People may have disagreed with him, but they never doubted if he said something that it was true. It is a different age today. The old concept of an authority figure being one that everybody would defer and nod to, that’s not true in america today. That’s basically a good thing.

We live in an age where some kid sitting in his underwear at his computer doing a blog has the capacity to change the way people are questioning something relating to Dartmouth. They say, “oh, I didn’t know that was true.” my word on that becomes simply another word. I get frustrated, but that’s the world in which we live.

I’m curious about the near impossibility of juggling competing demands of a prestigious undergraduate college, three graduate schools and a medical center. And fundraising. How do you carve out time for yourself?

Well, I have the advantage—or disadvantage—of living and breathing Dartmouth 24 hours a day. I don’t feel encumbered by that. I’m blessed to have a spouse and a partner in Susan, who also lives and breathes Dartmouth. We try to have an evening when we get away and don’t talk just Dartmouth, but it’s hard to find such times.

Being president of Dartmouth does not mean you’re the master of all you survey here. It’s a pretty complicated place. I am lucky to have a great team of senior officers, deans and vice presidents I can work with closely. I quit trying to imagine I could manage everything myself. I know the place pretty well because of the time I’ve spent here in various roles of administration. So I’m able to ask pretty good questions. most of the time when I’m asked questions I’m able to give pretty good answers. Being president of an institution like this means staying focused on being able to articulate values and purposes as much as you can and to stay focused on what you do to represent the College well.

If you follow some of the literature on college and university presidents, among their major complaints is the time they spend fundraising. I’ve never complained about that. I have dreams for Dartmouth. I have students and faculty I want to support. That costs money, and I’m more than happy to go out and talk to people about the wonderful opportunity they have to enrich their own lives as well as to make Dartmouth better and stronger. The current environment is a more difficult time to be out raising money. But I’ll talk about Dartmouth with anybody, anytime.

What have you enjoyed about being president of Dartmouth?

I’ve often described the presidency of a place like this as being on the one hand like the CEO of any organization. Before the current economic downturn we had $5 billion-plus in assets and a $700 million annual operating budget and a partnership with a major medical center, which is quite an expensive and expansive operation.

So I deal with a whole range of issues the private-sector CEO deals with. I have to deal with regulations on health and safety and labor. And in addition we have federal oversight because of our grants, a lot of paperwork we have to do. I spend a lot of my time meeting with colleagues, meeting with committees, meeting with groups, and much of it to do with what I call the green-eyeshade part of the job.

What I call the headmaster part of my job is that part where I get out and about and see students at lunch and go to plays and performances and athletic practices and games. I talk to faculty and coaches and people I meet on the Green. That’s the important part of the job. I get energized by being out talking to students and faculty and staff and coaches about what it is they’re doing. I think it is crucial to enjoy Dartmouth students, because that makes everything else very worthwhile.

Were there students when you were teaching who made you think, “Well, that’s why I’m here?”

Sometimes an alumnus repeats something I said in the classroom. A few years ago I was talking to somebody who had just made a major gift to his class reunion. and he said, “You probably don’t remember my final exam, do you, President Wright?” and I said, “no, I don’t.” he said, “Well, I overslept the morning of the exam, and I ran into some students who’d finished the exam and they said, ‘You’re in trouble, because he’s not going to give you a chance to make up for it.’ I kept thinking of every excuse as to why I missed the exam. I couldn’t think of any, and I came to your office and I just said, ‘I’m sorry, but I overslept,’ and you replied, ‘Well, that happens sometimes. Let’s see if we can schedule a different time for the exam.’” I was glad he remembered that.

Are there traps your successor needs to be aware of?

Dartmouth is a pretty sharp-elbowed place, but I’ve had the advantage of having been here 40 years. I enjoyed give-and-take with the faculty. I chaired faculty committees where I got in the middle of give-and-take. So I don’t think these are traps. Dartmouth has become in some ways more politicized in recent years. That is unfortunate, but the politicization is not subtle. Whoever comes in here is going to be aware of it.

Do people tell you what they think you want to hear?

Having been here for a number of years Susan and I have a lot of friends in the faculty and administration. Our relationship with them changed after I became president, as it necessarily does. I don’t mean that it became more strained. These are some fairly candid people. Students and faculty, as you know, are always pretty direct, and alumni are. I wouldn’t pretend for a moment that I always get everyone’s most candid assessment, but I think I generally know what’s going on.

When you talk to alumni, what criticisms do you hear?

Some of this, I think, is the result of politics: “are you really trying to change it into a university?” or “are you really trying to end the Greek system? are you really somebody who doesn’t value athletics?” my answer is pretty clear on all of these things.

Once you can really talk about what we’re doing, the sort of place Dartmouth is, I don’t think my vision for Dartmouth is appreciably different from that of most alumni. Some of them may not always understand my view, but I don’t think there’s much fundamental disagreement about the sort of place Dartmouth is and what it is we’re trying to do.

Some people have been mobilized over one or another assertion in recent years, but most Dartmouth alumni—certainly the survey data that I’ve seen—are pretty happy with the fundamental direction of the College. They may not like one thing or another, but Dartmouth is Dartmouth. It’s fair and appropriate to dispute one thing or another. These are well-educated people, after all.

Looking at the dissidents who filed the latest lawsuit, do you have any idea what percentage of alumni they represent?

Anywhere from 10 to 20 percent of Dartmouth alumni express dissatisfaction with the nature of the College. Probably half have been dissatisfied from the outset. We have people who leave at graduation and never look back. Some were not satisfied with the experience they had here, others thought the experience was fine but now they’re on to the next phase of their lives. Among those who are dissatisfied, I’ve certainly spent time trying to talk to some of them. I keep reminding people that if you talk about the quality of the student experience, the quality of the faculty, the importance of Dartmouth being a place that values that relation- ship between faculty and students, I’m not sure there’s great disagreement. I think some people are dissatisfied whether we pursue those things properly or not, and all I can do is stay focused on what I think is important. I’m always willing to explain, to debate, to discuss with people what’s going on.

Is it possible the bulk of Dartmouth graduates are satisfied with the College, but that they’re not involved because they’re too busy and they’re not paying attention?

I think that’s true, and some of them don’t care that much about some of these things. Some people care with a tremendous passion and intensity whether or not there is equity on the board of trustees. Other people are indifferent. In fact, they get fairly frustrated hearing about it from both sides; it’s not part of their lives and they don’t know why people are getting so worked up.

What makes Dartmouth a target for litigation? Are some of the people behind this not Dartmouth graduates?

One of my great frustrations is the people behind this who are providing the financial support don’t self-identify. Something about that suggests to me they’re probably not Dartmouth people. Generally Dartmouth people are willing to publicly say so. If one wants to try to win over Dartmouth alumni you don’t take a full-page ad in The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times. It’s not the most effective use of money.

You’ve said being able to articulate values and purposes is important for a college president. How do you grade yourself?

That’s a hard one for me to assess because the grade has to be determined by the audience. Much of what I talk about in terms of Dartmouth’s purpose has to do with providing for our students an education and experience that will enable them to live rich, full lives. I don’t for a moment imagine any president has the capacity to turn around lives. What you can do is continue to nudge and reinforce those values that are important. It has to be about more than the rhetoric. It has to be about a certain consistency in what you say an institution stands for and what we’re trying to accomplish.

Does a college president have responsibilities to comment publicly on issues of society or education?

I’m not certain people are sitting around waiting to hear what college presidents have to say about matters of public policy. I have spoken out on some matters having to do with veterans lately, but it really has to do with providing opportunities for education. I recently participated in a commission on education—not just higher education—that the College Board set up. I learned that our high school graduation rate is lower now than it was 35 years ago. We are not providing educational opportunities the way we should. You know, education is not just another national interest group. It’s part of a national infrastructure, and we need to invest in that infrastructure.

What must be done to adequately prepare high school students to succeed in college?

We need to do better in preschool education. In the vocabularies of kindergarten-age kids who have been to preschool and those who haven’t there’s a tremendous variation that we need to correct.

We need to do a better job of college counseling. I think all high school curricula should be aimed at college prep-type courses. even if one doesn’t go to college the fundamentals of math and science and humanities and history are important.

What has happened in our country over the last 50 years has not been an erosion in college curricula, it has been an erosion in high school curricula. Despite the warm memories of your and my generation, Dartmouth did not ever require a course in Shakespeare. Most people our age read Shakespeare and studied European history in secondary school, and some of us pursued it with great enthusiasm in college. But to have colleges play this remedial role is fundamentally altering what happens, particularly in a relatively small institution like Dartmouth.

You didn’t become a voracious reader until you were in the Marines. How do you encourage that love of reading in kids?

You know, we have grandchildren, seven of them. We send them books and ask what they’ve been reading. I don’t care what they read. I started reading comic books. My mother used to roll her eyes at the comic books, but you know, I learned vocabulary, and I moved from them pretty easily to books and haven’t stopped reading since. Well, I’ve slowed down my reading more since I’ve been president.

Do you have a list of books you want to read when you retire?

I’ve been reading more about the middle east and the war in Iraq. I have an interest in political history I want to return to. Fiction I’ve always liked. I tend to like mysteries.

Do good college presidents have to come from within academia? David McLaughlin ’54, Tu’55, was a CEO and Dickey a lawyer-diplomat, but the recent trend has been academics.

It’s not surprising. This is a more specialized position than some people think. The only two things that most people think they can do better than the person doing it is to run a baseball team and to run a school, because those of us who follow baseball can always second-guess, and we’re all products of schools. It’s something we think we know with some familiarity.

Institutions like Dartmouth are incredibly complicated. I don’t think I would say somebody has to be an academic. But it’s a tremendous advantage in running an institution like this.

Do alumni ever tell you they want to come teach here?

I often have somebody say, “I’m thinking about retiring. I’d like to come up and teach a course at Dartmouth.” and I say, “Well, I’m tired of teaching history. I think I’d like to go down and run your law firm for a while.” There are places for this to happen, but academic life is a career choice. It’s something most of us have chosen to do, and people who go into academic life don’t do it necessarily for money and power. I think the opportunity to pursue in-depth something they really value and to be in a classroom with students is just a remarkable blessing. It’s one of the great things in life.

You initially thought of becoming a football coach. Have you suggested plays to head coach Buddy Teevens ’79?

I joke about going down and sending in some plays. But, no, I have not. Goodness, I don’t understand some of the sets they’re doing today. It’s a different world.

How do you explain the winless football season to alumni?

I remember Buddy as an exceptional quarterback, and I have the advantage of remembering him as a student in one of my history classes. he’s an exceptional coach, an inspirational leader and his values are Dartmouth’s values. I think we should be competing for the Ivy League championship consistently, and Buddy has that goal. Each year his teams have gotten better and so has the rest of the league. This past year was difficult, but it’s a very young team. I have every confidence some of the freshmen and sophomores will see an Ivy League championship.

Let’s turn to the academic side of Dartmouth. You spoke of the sharp elbows in academia.

Well, at Dartmouth there are sharp elbows in academia, meaning that people speak out directly and candidly. This is characteristic of higher education. Dartmouth alumni and the students have sharp elbows. We speak our mind here. You just have to be prepared for that.

When you were in the classroom faculty members were teaching five classes a year. That was reduced to four.

The reduction started in the early 1980s. It was by way of being competitive in terms of recruiting faculty. The course load at Dartmouth is really the formal classes. What it doesn’t measure are the 250 students a year doing honors theses. It doesn’t measure the thousands of students a year who are doing independent study. It doesn’t monitor the couple of hundred students a year who are Freedman Presidential Scholars. We’re talking about the formal courses as being part of the class load, so it was an effort to reduce that. It’s something that has kept our faculty competitive. I’m impressed at the quality of the faculty we recruit today. I’m impressed at what they’re able to do as young scholars and by their devotion to teaching.

With your budget severely squeezed in this economic downturn, would it be desirable to ask them to teach more?

We have to be very careful that we recruit the sort of faculty we need, and I would worry about increasing their teaching responsibilities.

You make the point that nearly two-thirds of courses at Dartmouth have fewer than 20 students. That’s down substantially from 10 years ago. Why is it important?

Students and faculty today enjoy those sorts of classes. They’re good interactive learning experiences and, let’s face it, when I was teaching some of my classes in the 1970s I would have 150 or 200 students in my courses in 105 Dartmouth hall. I’m surprised I still remember as many students as I do who were in those courses. There’s nothing wrong with a standup lecture format, but it’s not the way this generation learns most effectively.

Tuitions are increasing faster than family incomes. Why have universities and colleges found it so hard to stay within this inflation rate?

A couple of factors describe costs, and one is that we’re very laborintensive. at the best colleges there’s a tremendous competition for the best faculty, and we certainly compete for the best.

We are very technologically driven today and it’s cutting-edge technology. We’re buying at the front end, when it’s more expensive. We purchase a lot of goods and services internationally, and in recent years the dollar has not fared well.

We can talk about how it’s fine to go back to a monastic dormitory life and, darn it, the best students will still come. I don’t know that they would. Fitness facilities, arts opportunities, a range of dining options, comfortable, quiet living spaces—these are part of what the best students are looking at today.

In the time I’ve been at Dartmouth we’ve had some of the lowest growth rates of tuition over the last five or six years. We’ve shifted more and more to a utilization of endowment, and that’s what complicates the situation we’re in now.

Is this belt-tightening something colleges have to live with?

I’ve been involved in higher education now for 40 years, and I think we all have to recognize that the lean years in the history of american education far exceed the growth years. We’re entering into a lean-year phase right now and the crucial thing is to try to protect the quality of the Dartmouth experience. This is the third time I’ve gone through this exercise—as dean of faculty, provost and president—and this is easily the most severe. We have to be very careful as we look at the budget to remember that the richness of Dartmouth really comes from our capacity to provide opportunities for students to pursue their interests and to learn to excel in things that are important to them.

So when you get into cutting budgets there’s always a danger of cutting back those things that people define as on the margin or the periphery. For some significant group of our students these are not marginal, they’re central to the way they enjoy Dartmouth. We’ll have to make reductions, but we have to be careful not to make Dartmouth some place that’s not Dartmouth.

Is someone with a Dartmouth degree better prepared to compete in a tough job market?

Dartmouth graduates have a tremendous capacity to be independent and to imagine new and different things. That’s always a strength, and perhaps it’s a best strength now. Dartmouth students have learned to compete. I’ve told every class I’ve ever welcomed here that it’s a remarkable process of competition to get into Dartmouth, but you don’t have to compete with each other to be at Dartmouth. The competition now is with your own ambitions and aspirations.

Applications for admissions have increased 63 percent in the last decade. Why?

It’s easier to do multiple applications today, and we’re the beneficiaries of that. But since we haven’t expanded the student body it also means there are more very strong applicants that we have to say no to. I don’t think any of us should take particular pleasure from that. There are very good applicants every year.

The acceptance rate for applicants has dropped from 21 percent to 13 percent. Have you given any thought to expanding the student body?

About 20 years ago we used the year-round calendar to increase the student body. I’m not sure the campus infrastructure—be it physical facilities, size of faculty or range of programs—has kept up with the expansion of the student body. Most Ivy League schools have expanded in recent years. We’ve never had a serious conversation about doing that.

You’ve also been doing need-blind admissions. Isn’t this very expensive?

Sure it is. We’ve increased our financial-aid budget significantly during my presidency. It’s money well spent. Dartmouth has to be a place that is accessible to students regardless of their families’ economic situation. That’s been a principle here for a long time. We could fill the student body here with people who could pay full tuition, remarkably interesting and talented kids. But we would not get the most talented and the most interesting among them, because students really do want to come to a place that’s diverse. If we claim the leadership of our society will continue to be people with an education such as that at Dartmouth, we have an obligation to make certain this is not an opportunity available only to the select few.

What is the biggest divide separating students now? Is it economic, social…?

Aconomic. I don’t think the Dartmouth students who come from backgrounds of wealth try to call attention to themselves. They’re generous and gracious, they’re not condescending. But they can select things in ways other students may not be able to, and over a period of two to three and four years that becomes magnified. I don’t know if there’s any greater sense of economic class than when you were a student. Maybe it shows itself in different ways. Not as many students work when they’re at Dartmouth. Every student should have some job on the campus as far as I’m concerned, but if they don’t need to, I have enough on my plate without trying to manage an employment service for students.

There’s no doubt that working is a good thing, taking jobs that they’ll never take again. When I was an undergraduate I worked as a bartender. I worked at a golf course. I worked as a janitor. I worked in a plant making Swiss cheese. I worked underground as a miner. I’m not looking to go back to do those things today, but they’re all part of who I am.

The summer job has taken on a different meaning today. Stu- dents are far more career oriented. When you and I were the age of our current students a great summer would be to go work on the Cape. Our students at Dartmouth are trying to find summer jobs that will be a step toward something they want to do with their lives. I wish it weren’t quite that way, but that’s not for me to try and manage.

Is this necessarily bad?

I keep telling students and their parents that lives are not things to be planned out. I worry about the way students select courses and majors today. I tell them a major is not a life choice, and a course you select for this spring is not a career choice. Take courses that you want. Get an education and your life will take care of itself.

When I was a student the difference between fraternity and non-fraternity assumed the proportions of a caste system.

I think that’s less true today, don’t you? The Greek houses are far more open than they were in terms of membership obviously, but even for non-members to enjoy the houses when they’re having social occasions. But if you look at Greek organizations, financial-aid students are not participating at the same level as nonfinancial-aid students.

You’ve talked about the Student Life Initiative not being well presented. A decade later, has your goal been reached?

We did accomplish a number of things we set out to do. I think we stumbled coming out of the box, which made the process far more complicated, far more difficult to get people engaged. But Greek houses have evolved and changed, which is not to say they have reached perfection. Perfection is always an ambition and never an accomplishment, and that’s okay.

What are your retirement plans?

I don’t know. I exaggerate when I say this, but there’s an element of truth to it. I have said I can imagine walking out of here in June and putting my arm around Susan and saying,“What are we going to do next?” Susan wants to know by dinnertime tonight what we’re going to do then. If I keep telling our students that lives are things we enjoy rather than to be planned, I have to be careful trying to plan the rest of my life now. I know some things will take care of themselves. We have seven grandchildren I would like to see more of. I want to spend some time working on a publication of some of my Dartmouth speeches. I have to get my arms around my personal archives and find out which of them go into the library, which I just want to throw out and which I want to keep. I have been approached by a number of groups to be involved in veterans’ activities.

We have a place at Sunapee [New Hampshire] and we’re going to move over there. The best thing I can do for my successor is not be around the Green every day.

What Dartmouth links will you maintain?

I’ll decide that over the next year. People have asked if I would go back into a classroom, and I’m not going to. Dartmouth faculty need to be on top of their fields. I can go in and be warm and fuzzy and avuncular, but I can’t pretend that I’m on top of my field—and the students who come here deserve better than that.

What is the biggest unfinished business you bequeath to your successor?

I would have loved to have finished the capital campaign. I wanted to get it done before I hand the keys over, but that’s not likely to happen.

What achievement makes you proudest?

I’m pleased with the facilities. I like the quality of what we’ve been able to bring to the campus. But Dartmouth is about students and faculty learning and exploring together. I take my greatest satisfaction in the quality of the students and the growth and support of the faculty and the sort of experience they have at Dartmouth.

How would you like to be remembered?

I really haven’t thought about it. You can get a stonemason to carve into the granite any sentiment you want. I haven’t quite gotten there and I want to reflect on some things. I would want to be remembered as a teacher, I think. Over in the President’s House Mrs. Dickey did needlepoint chairs of all 12 presidents who served before John Dickey. Each of these chairs has something that represents some of the accomplishments of that president. Some of these are pretty busy chairs. I’ve been asked if I want things having to do with the size of the endowment or programs for faculty. And I said, “What I would like for my needlepoint is a lectern in front of a blackboard.” I’d like that to represent my time here.

Is there a predecessor at Dartmouth to whom you’ve looked for inspiration?

I have admired all the presidents under whom I’ve served. Each of them brought something different to the table.

But if you go back to the historic presidents I like William Jewett Tucker [class of 1861]. President Tucker came to Dartmouth at a very difficult time in 1893. Dartmouth then was a finishing school largely for New Hampshire boys, and he decided Dartmouth was going to be a larger, stron- institution. He wanted the faculty to move beyond the 19th century classical curriculum to do more in the sciences and the social sciences. He started building the facilities here. He started recruiting students nationally. He developed the first school of business in the country. He knew that in the 20th century Dartmouth’s niche was not going to be defined by being a small school in New Hampshire. Mr. Tucker very much valued the roots and the values of Dartmouth, but he also knew that staying true to your values does not mean you don’t change.

I’m very much rooted in the values of Dartmouth, but you do not maintain those values in a changing world by staying static.

What will you miss most?

I’m going to miss walking across the Green and saying hello to students. That’s something that was special when I first walked across the Green 40 years ago.

CHRISTOPHER S. WREN is a former New

York Times foreign correspondent. He lives in

Thetford, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May | June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

Feature

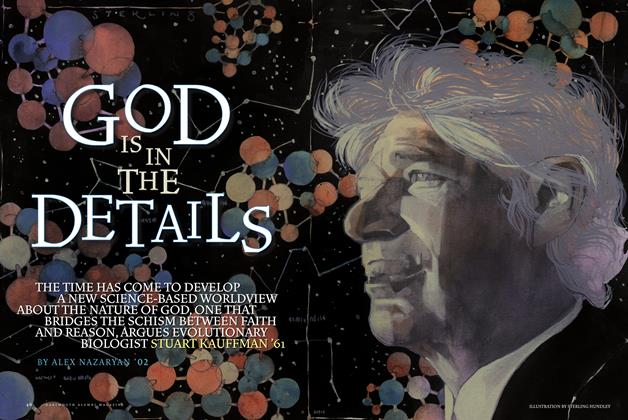

FeatureGod Is in the Details

May | June 2009 By ALEX NAZARYAN ’02 -

CLASSROOM

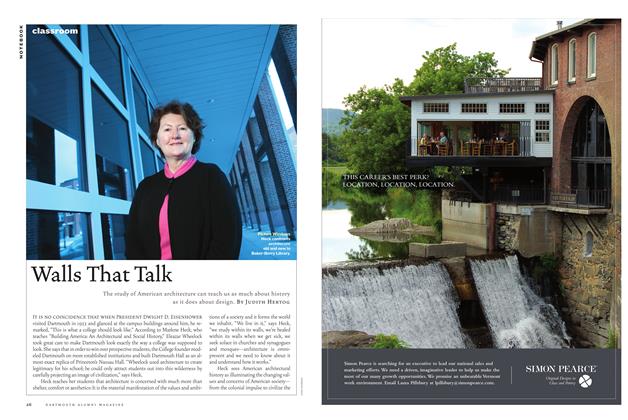

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May | June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May | June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

SPORTS

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May | June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96

CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57

Interviews

-

Interview

InterviewPicture Perfect

MARCH 2000 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

INTERVIEW

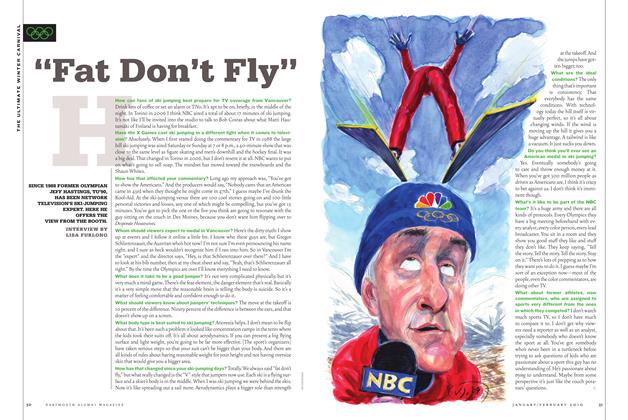

INTERVIEW“Fat Don’t Fly”

Jan/Feb 2010 By LISA FURLONG -

Interview

InterviewLook Who’s Talking

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Madison Wilson ’21 -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“Let’s Make This Memorable”

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Sean Plottner -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“Unbelievable”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2022 By Sean Plottner -

Interview

InterviewThe Archivist

Sept/Oct 2005 By Sue DuBois ’05