On life as a storyteller and writer

“I didn’t grow up thinking of myself as having a political identity. I thought of myself as a mixture of backgrounds. My [Turtle Mountain Chip- pewa] mother thought about it, though, and she made sure I applied to Dartmouth. My father worked with financial aid to be sure he could send me on a teacher’s salary. he even joined the National Guard to earn more. Dartmouth was generous and my tribe helped, but my parents and six siblings sacrificed for me. I chose Dartmouth over Sarah Lawrence because it offered me $100 more. That’s the kind of margin we’re talking about.”

“Going to Dartmouth from North Dakota was an outrageous new adventure. I was less concerned about the academic challenge than I was about changing planes at Logan Airport.”

“The first time I walked down Webster Avenue a burning mattress was thrown from a third-floor window and landed right in front of me. Being from North Dakota and being a somewhat sensible person, I didn’t go back until a party at Tabard my senior year.”

“I fell in with the artsy people, those who wrote madly and hung out at the Top of the Hop, staring gloomily out the windows into the vast nothingness beyond Dartmouth, staring with intensity at the cloud banks.”

“My first paper was for Alan Gaylord and I titled it ‘Falstaff, the Portly Polygon.’ I guess I was trying to make the point that Falstaff had a many-sided personality. I had written perhaps two papers in my life. Professor Gaylord kindly helped me with structure—and told me I should read more.”

“I come from two strong storytelling traditions, Anishinabe and German. Both my father and mother are wonderful storytellers, very funny, very down-to-earth. They find something interesting and humorous in everything happening around them.”

“Sometimes I’m surprised by what I see on paper. I recognize my handwriting. I believe writers and artists are able to create because they feel the influence of what was once called the muse. I think for me it has to do with my ancestors’ voices and stories that were never told.”

“I never know whether a character will return to me or not. At Dartmouth [artist-in-residence] Hannes Beckmann told me, ‘Just leave the door open.’ It was a great piece of advice.”

“When I write I still sit in the same big, comfy chair I had in New Hampshire, using a board across it, and write longhand in a notebook. I work at the same time every day, leaving my evenings free for my family. Working isn’t always writing. It’s reading, thinking and meandering through history.”

“I jot notes on everything. It used to be bar napkins, then it was howard Johnson’s napkins, then diner napkins, then my children’s leftover school papers. All are stuck in my notebooks. When I walk my dog each morning I always have scraps of paper with me.”

“I don’t often read anything written about me. I won’t read a review for a year or so after a book comes out. I don’t want to be self-conscious. Sometimes a reader or critic will find something in one of my books that I had no idea it contained. I feel full of myself for about three seconds.”

“I am a lover of small communities, including those within big cities. I like being close to family. I live in Minnesota because I can get to my parents in a few hours, and my sisters live within a block. We like to stick together.”

“When aspiring writers ask for advice I tell them: ‘Exhaust all other possibilities.’ Then if all you can do is write, never give up.” “There is no one way to take a piece of writing. It’s up to the reader to decide.” “There is a thirst and hunger for narrative. No matter how many media outlets we invent, it’s all about telling one another stories.”

NOTABLE ACHIEVEMENTS: One of America’s most honored writers for her fiction featuring quirky reservation and small-town characters who reflect her Chippewa and German heritage; 2009 Pulitzer finalist for her 13th novel, The Plague of Doves; has written and illustrated three children’s books OTHER INTERESTS: With her sister Heid E. ’86, founded Nativefocused Birchbark Books store in Minneapolis, which features an old confessional (“the forgiveness booth”) that bestows “blanket absolution;” the sisters teach an annual writing seminar at Turtle Mountain Community College in Belcourt, North Dakota EARLY JOBS: Included breakfast grill cook in Thayer Dining Hall, sugar beet hoer, road construction flag worker, writer-in-residence at Dartmouth, 1980 FAMILY: Mother of six including Aza ’11; in addition to Heid E. has sister Angela ’87, DMS’94

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

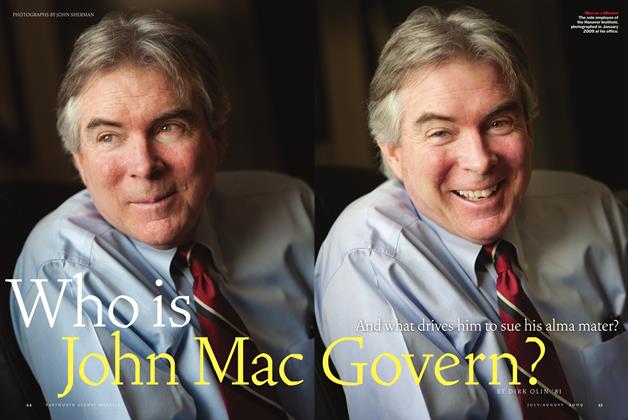

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July | August 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

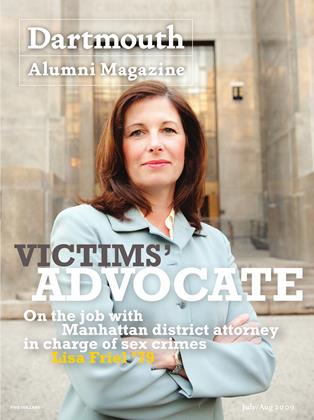

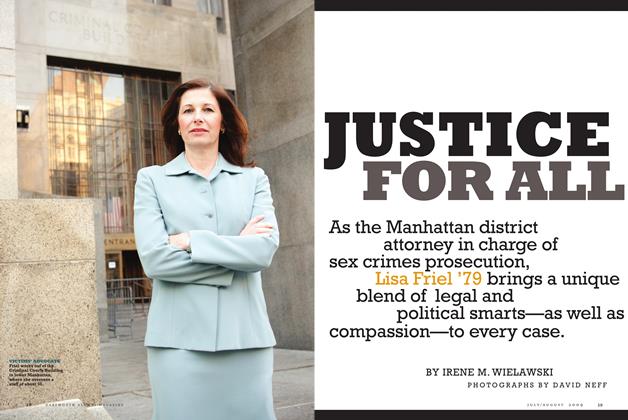

Cover Story

Cover StoryJustice for All

July | August 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

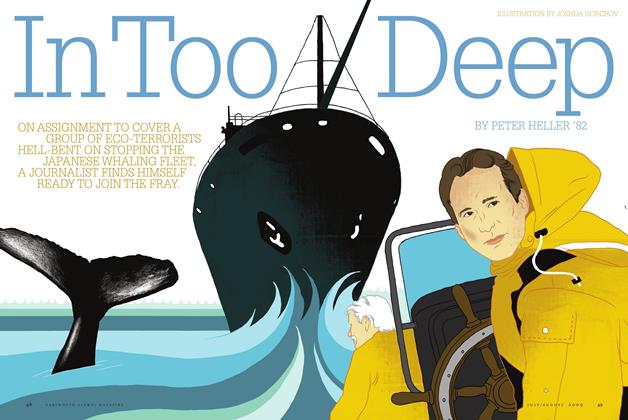

Feature

FeatureIn Too Deep

July | August 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

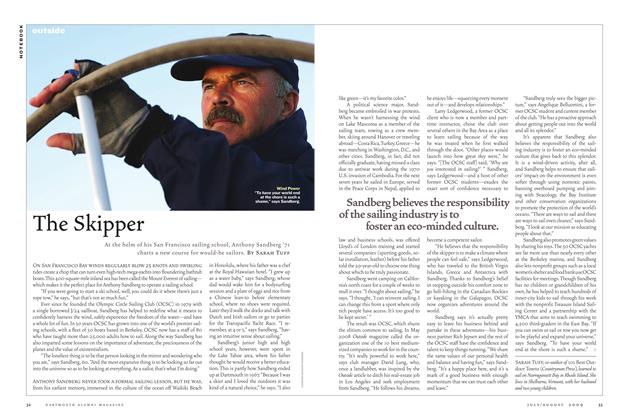

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July | August 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FILM

FILMLife’s Big Questions

July | August 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02

Lisa Furlong

-

Article

ArticleAnnette Gordon-Reed '81

July/Aug 2003 By Lisa Furlong -

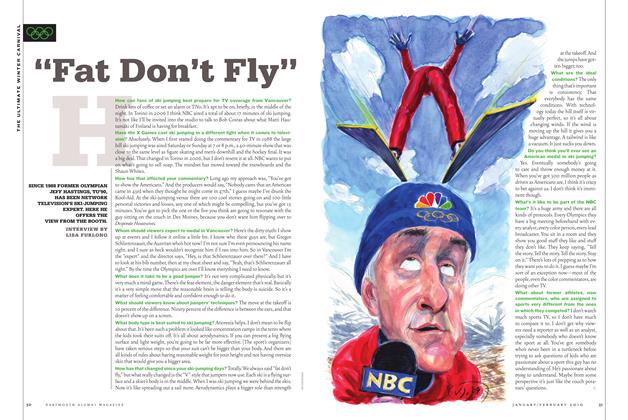

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“Fat Don’t Fly”

Jan/Feb 2010 By LISA FURLONG -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdVictoria “Tory” Rogers ’83

Jan/Feb 2012 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdGeorge Anastasia ’69

Mar/Apr 2012 By Lisa Furlong -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDAnn McLane Kuster ’78

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2019 By LISA FURLONG -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDDhiraj Mukherjee '91

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By LISA FURLONG

Continuing Ed

-

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdFred Berthold Jr. ’45

Nov/Dec 2005 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdBobby Charles ’82

Jan/Feb 2006 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationDavid Mott '86

Nov/Dec 2007 By Lisa Furlong -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDLorna (Mills) Hill ’73

May/June 2009 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdNick Lowery ’78

Jan/Feb 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDAllan A. Ryan ’66

JULY | AUGUST 2022 By LISA FURLONG