Justice for All

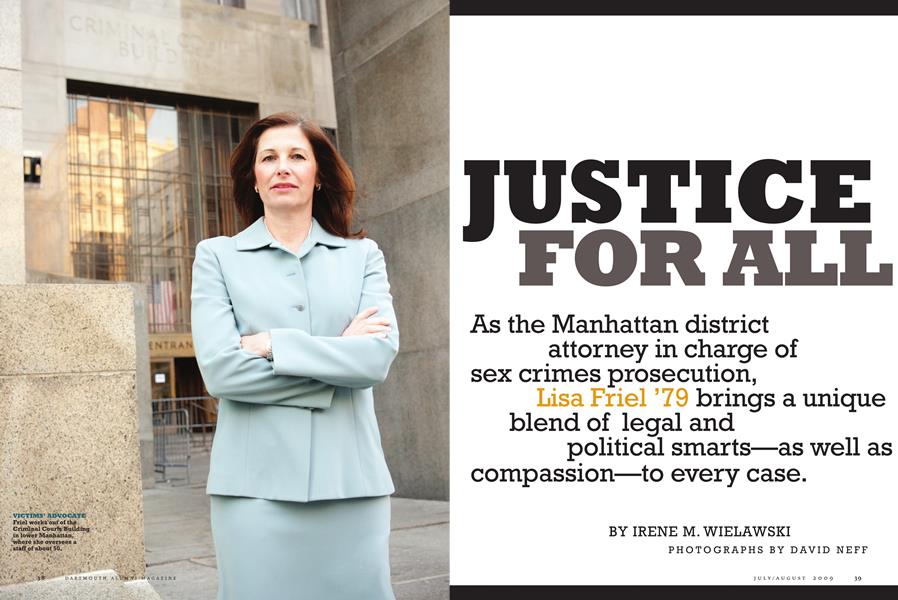

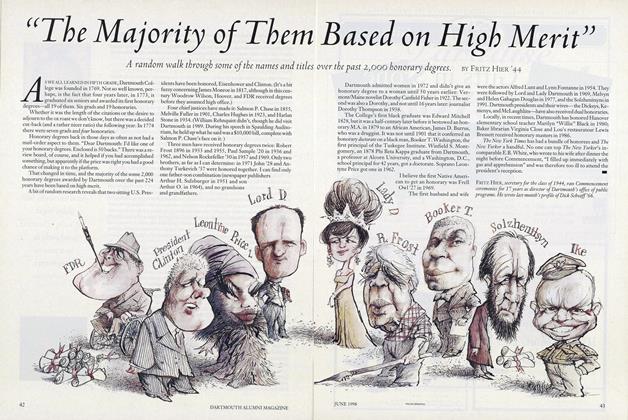

As the Manhattan district attorney in charge of sex crimes prosecution, Lisa Friel ’79 brings a unique blend of legal and political smarts—as well as compassion—to every case.

July/Aug 2009 Irene M. WielawskiAs the Manhattan district attorney in charge of sex crimes prosecution, Lisa Friel ’79 brings a unique blend of legal and political smarts—as well as compassion—to every case.

July/Aug 2009 Irene M. WielawskiAs the Manhattan district attorney in charge of sex crimes prosecution, Lisa Friel ’79 brings a unique blend of legal and political smarts—as well as compassion—to every case.

Even lawyers who have prosecuted thousands of rape cases never forget their first one. Unlike homicides, most sexual assaults leave behind victims who remain painfully alive, immersing police and prosecutors in the soul-searing damage caused by such intimate violation.

Mendelson Friel learned this as a young assistant district attorney in New York City, tapped to handle a rape prosecution because a more senior colleague was overloaded. Only a few years out of law school, Friel applied her characteristic diligence to the case, not suspecting the impact it would have on her life—and the trajectory of her career.

Recalls Friel, who heads the sex crimes unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, of the victim: “She was so much like me. We were the same age. She was a Penn graduate, I was Dartmouth. I identified with her.”

The young woman’s assailant, intent on burglary, had pried open a bathroom skylight and, finding her alone in the apartment, raped her. During the police investigation the victim identified the man from mug shots, but police were unable to find him until two years later. That’s when Friel got the case. Her initial conversation with the victim left a profound impression.

“It was two years after the crime and she was still a mess. She’d moved out of the city to try to start over but [the rape] still haunted her,” Friel says. “She was frightened and wasn’t sure she could handle testifying, reliving it all over again. Sex crimes prosecution is not for people who don’t want to handhold. You have to be ready to take the calls, sometimes every week, [those who have been assaulted] are so anxious. ‘Is the perpetrator still in jail?’ ‘Is everything with the case still okay?’ It’s an area so full of self-blame and questions of ‘What did I do wrong?’”

In the end, confronting her attacker and delivering the evidence necessary to lock him up was transformative for the young woman. Even before the guilty verdict she thanked Friel for helping her muster the courage to testify.

“Boy, did I ever feel I made a difference,” says Friel. “From that day, I was hooked. I realized this is the perfect job for a people person like me.”

Slender and petite at 5-foot-2, with shoulder-length chestnut hair and a wide smile, Friel comes across as a people person. She is warm and engaging in conversation and an attentive listener. If you didn’t know her record of success against rapists, sex slavers and child molesters, you might think elementary school teacher, psychologist—or soccer mom, for her animated tales of life with three teenagers.

But those who know Friel well warn against underestimating the analytical, legal and political skills that underlie her passion for helping others.

Although Friel notes that performance can’t be measured solely by win-loss stats, given the many judgments involved in bringing a case to trial, her conviction rate is more than 70 percent overall and more than 90 percent in cases involving rape victims who did not know their assailants.

“She’s smart, fair and very effective as a lawyer,” says Robert M. Morganthau, the legendary Manhattan district attorney who hired Friel 26 years ago. “She’s also a great person and widely looked up to as a role model inside the office and for her expertise by lawyers in the field of sex crimes.”

Indeed, Friel heads the sex offense subcommittee of the New York State District Attorneys Association, testifies regularly before the state Assembly in Albany and even lectures internationally. She was invited by the Norwegian government last March to give a seminar for law enforcement officials on sex crimes investigation and prosecution, and to discuss legislative initiatives with members of parliament.

Friel does all of this in a low-key style that contrasts sharply with that of her predecessor as sex crimes chief, the nowbestselling mystery author Linda Fairstein. Fairstein, who stands more than 6 feet in three-inch stilettos, by many accounts could scare the truth out of just about anyone. Nevertheless, Friel is equally determined to win.

“She’s a pit bull when it comes to investigations,” says Sue Morley, former commanding officer of the special victims division of the New York City Police Department. “Her caring really comes across when she talks about cases, but she won’t compromise her standards on evidence gathering. The point she imparts to our detectives during training is that it’s not enough to have probable cause just to make an arrest. You have to be able to support the probable cause in court. Otherwise, you leave the victim up there on the stand by herself trying to make the case on her own word.”

A complicating aspect of sex crimes prosecution is that in about 80 percent of the cases the victim and perpetrator know each other, leading, Morley says, to “deficiencies” in the accounts of both parties. The alleged victim may not want to admit she was intoxicated on drugs or alcohol. A 14-year-old who believes she’s madly in love with a 35-year-old man may refuse to cooperate, despite her parents’ demand that police arrest the man for statutory rape. The accused may claim sex was consensual, based on a prior relationship with the complainant.

These factors don’t make underage or coerced sex any less criminal, but they add a lot of detail work to investigations, delaying arrests. This, Morley says, can put detectives in a bind, since they’re also under pressure within the police department to make arrests and move on to the next case. There’s also what Morley calls “old school” police thinking that “DAs don’t run investigations.”

“I won’t kid you, Lisa’s insistence on the best investigation possible—cell phone records, physical evidence, crime scene evidence like video tapes on buildings, witness interviews, back-ground checks—before the arrest can make things a little tense,” says Morley. “But the cops respect her. And she’s very smart about navigating the police department. She doesn’t throw her law degree around or talk down to anyone.”

Friel’s ability to forge rapport with the various constituencies of her office—police, crime victims, their families, witnesses, judges, defense attorneys, legislators and a host of others—may be proof of her innate “people skills.” But the larger purpose of her efforts, Friel says, flows from the values gained through her “dead-on middle class” upbringing in suburban Haworth, New Jersey. The oldest of three daughters of a garment manufacturer and his homemaker wife, Friel remembers a happy childhood that revolved around school, sports and community life. She played every kind of ball game and continued to do so at Dartmouth on the women’s tennis and basketball teams. She also shared her father’s devotion to the New York Giants, a passion—one might say obsession—that continues to this day. Her parents were very civic-minded, campaigning for candidates and serving on town commissions and in community organizations.

“My whole orientation is still, 25 years later, a reflection of how I was raised,” says Friel. “My father and mother really believed in doing for others. When I was filling out my college applications and had to write about someone I admired, I wrote about my dad and how ethical he was and the value he put on giving back to his community.”

Dartmouth wasn’t on Friel’s initial college list because, although she ranked fifth in her senior class at Northern Valley Regional High School at Demarest, she didn’t think she was smart enough for the Ivy League. “I’m the classic overachiever,” she laughs. “My SAT scores were good but not great. But my mother, who had never gone to college, said I should shoot higher.”

Friel saw that Northern Valley’s valedictorian, Debbie Krieger, was applying early decision to Dartmouth and decided to give it a try, especially after a visit with her parents to Hanover, where she fell in love with the beauty of the campus. Krieger, now Debbie (Krieger) Jennings ’79, got in but Friel was deferred. Her acceptance came the following spring, helped, Friel believes, by Haworth neighbor Bob Allen ’44, who made phone calls on her behalf. “I was a little worried about how I’d do because I thought I was going to be surrounded by geniuses,” she says.

Friel credits her academic success to hard work, though fun was an equal part of her Dartmouth experience. Indeed, it was an exuberant beer pong match at a Kappa Sig party freshman year that helped propel Friel into yet another passion: coaching basketball.

“I took a step back to make a shot and slipped on the wet floor and went down,” Friel recalls. “My left knee dislocated. I’d dislocated it a few times during high school but our family doctor never really had an explanation for why. So there I was, curled up in a ball in the beer on the floor in terrible pain and very embarrassed. Finally, I managed to roll over and pop the knee back in. The next day, it was really swollen. My roommate helped me get to Dick’s House, where they gave me some crutches. I remember going back to return the crutches the following Thursday, which happened to be orthopedics clinic day. The person at the desk said, ‘Why don’t you let the doctor take a look?’ I didn’t want to stay, because I had varsity tennis practice, but the person said, ‘Hey, you’re here, it won’t take long.’”

Dr. Robert Porter, later the founder of the DMS sports medicine department and now an emeritus professor, was the orthopedist on duty. He quickly figured out that the reason for Friel’s trick knee was a congenital structural defect that could be corrected only by surgery. Friel had the left knee operated on by Porter at Mary Hitchcock, and the right knee similarly repaired during her junior year after she dislocated it while dancing at a Beta Theta Pi party.

The surgeries and long rehabilitative periods that followed pretty much ended Friel’s hoops career—not that it was all that spectacular, she’s quick to note. In addition to being short, Friel says her “mediocre talents” were no match for the players then-new women’s coach Chris Wielgus was attracting to Dartmouth. Seeing Friel’s disappointment, Wielgus invited her to coach the junior varsity team during her senior year and assist Wielgus with the varsity team.

“She was very passionate about the team,” Wielgus recalls. “She couldn’t play, but she didn’t want to walk away from it either. She already was volunteering as secretary to the women’s sports department, and I loved having Lisa around because she’s fiercely competitive and so am I.”

Friel stayed an extra year in Hanover after graduation in 1979 to continue coaching and prepare to apply to law school. She was accepted at the University of Virginia School of Law, as was her boyfriend; they married at UVA but divorced six years later.

As a law student Friel wasn’t sure what kind of career she wanted. Because she had loans to pay off she eagerly accepted summer-associate positions with well-paying private law firms her first two years. The experiences turned her toward public service law, and when a colleague mentioned opportunities in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, Friel quickly applied.

“When I interviewed here, it just felt like home,” she recalls. “People were young and dynamic and committed to making New York City a better place. And as a prosecutor you have all the power to do the right thing. You can decide whether or not to prosecute, whether to plea bargain, how to sentence.”

The Manhattan DA’s office, located in the enormous Criminal Courts Building near City Hall in lower Manhattan, is organized into two main divisions: investigations and trial. In the trial division there are six trial bureaus, each with about 50 prosecutors. Within each bureau six seasoned prosecutors—meaning they have at least three years’ experience and have handled felonies-are assigned to sex crimes.

Friel started out in August 1983 as all newly hired assistant district attorneys do—assigned to a trial bureau and handling misdemeanors such as shoplifting or minor assaults. “You carry about 200 cases, so organization is key,” says Friel. She progressed to prosecuting felonies—more serious crimes in which the stakes are higher for both the accused and the DA’s office. Then, in 1986, Friel’s bureau chief handed her the Penn graduate’s rape file because the more seasoned prosecutors were busy with other cases. Friel became a specialist after that, excelling to the point of being tapped by sex crimes chief Fairstein.

“I was a deputy to Linda Fairstein for 11 years,” Friel says. “Even though we have different styles, we blended very well. Every day I worked alongside her I learned something. The fact is—and I tell this to the young prosecutors I now supervise—you can’t go before a jury and put on a fake performance, trying to be somebody other than who you really are. Even if you have all the evidence on your side, the jurors can spot phoniness, and it leads to a loss of trust in what you are telling them.

“Linda was masterful at getting the truth out of people. She could be very aggressive and effective that way,” says Friel. “But I’m not very tall, and in the early years I looked so young even the judges wondered if I was old enough to try a case. I certainly wasn’t going to win by intimidation. I’m more like, ‘Hey, something’s missing here….I’d like to help you but I can’t if you don’t tell me what happened.’”

Friel’s day typically begins at 6:30 a.m. amid wailing alarm clocks and the bustle of getting children off to school. Her youngest, Katie, is in ninth grade at Poly Prep Country Day School; the school bus stops at 7:15 sharp near the Friel family’s Brooklyn home. Then comes a 20-minute drive across the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan with son James, an 11th-grader who takes the subway near Friel’s office uptown to Regis High School. After dropping him off Friel typically heads for the gym, where she puts herself through an hour-and-a-half workout three times a week. (Ongoing knee problems have resulted in eight operations and led her to drop tennis and take up golf.) As others leaf through magazines or check the stock tables while pedaling the stationary bikes, Friel reads the New York Daily News for its coverage of the city’s crime scene.

Friel’s oldest child, Danny, is a freshman at College of the Holy Cross. The children’s father, James Friel, a fellow prosecutor whom Lisa married in 1989, died in 2002 of bacterial meningitis. “It was very hard,” Friel says simply. “The kids and I learned to talk a lot after Jim’s death. We still do. It’s made us very close as a family.”

Friel’s office bears witness to that. Amidst the case files are innumerable photos of Danny, James and Katie as gap-toothed first-graders, budding athletes or just plain kids clowning for the camera. An I-love-my-Mom poem written in a shaky grammar school hand by Danny is taped to a window frame, not far from some FBI wanted posters featuring sexual predators.

And then there’s the family “thing” about the New York Giants. At home the Friel den is painted Giants blue and red and decorated with team memorabilia, including a life-size fathead of quarterback Eli Manning. At the office visitors are greeted by the yellowing Daily News front page from February 4, 2008, taped to Friel’s scarred metal office door: “MIRACLE,” screams the headline. “Giants stun undefeated Pats to win Super Bowl.”

Friel acknowledges the pressures of juggling single parent-hood and career—especially one as public as hers. Her storied organizational skills and “compulsive” attention to detail sometimes let her down, like the day she mistakenly packed one of Katie’s white blouses with her business suit to change into for work after the gym.

“Needless to say, it was gapping all over the place—I had to wear my suit jacket buttoned all the way up so I didn’t shock people,” Friel laughs.

In a more serious vein, she acknowledges the intensity of on-the-job encounters. To alleviate the pressures on her staff born out of dealing with brutality on a daily basis, Friel cultivates an almost homey atmosphere. Hierarchy is subdued and everyone interacts on a first-name basis. Lunch is takeout at the conference table in Friel’s office, where investigators, paralegals, deputies and prosecutors gather to trade war stories, often in a droll can-you-top-this manner.

“It’s a kind of group therapy,” says Friel. “Lots of people get into this work because they want to help people. It’s very easy to want to believe everyone at the beginning and to hesitate to ask victims the tough questions. What you learn is to be skeptical, to distance yourself a little and think like a lawyer, building the factual case. The joke around here is that everyone comes into the unit empathetic but after a while you get to the point where if your mother came in and said she had a tuna sandwich for lunch, you’d say, ‘Oh yeah? Show me the receipt.’”

On a recent and not atypical day Friel was helping her deputies, including the lead prosecutor, sort out a case involving a teenage girl who said she had been raped. The circumstances of her account didn’t completely check out. The girl had told her parents the man was a stranger and that he’d forced her to the rooftop where she was assaulted. Investigators, however, found evidence of cell phone exchanges between the man and the girl. It didn’t mean she was lying about the rape, but it did suggest she wasn’t being truthful to either her parents or investigators about how she happened to be on the roof with her assailant. To top it off, the girl’s parents were suggesting that racial prejudice was behind investigators’ continued questioning of their daughter.

“They, of course, believe their daughter and they’re upset with us that we don’t automatically accept her story,” says Friel. “The difficulty in these cases is this human element—the natural reaction of parents to be advocates for their child, the natural tendency of teenagers to leave out details that might get them in trouble because they did something their parents told them not to do and all the psychology involved.”

In real life such cases are always more complicated than simply getting to the facts. “Even though our job is to prosecute a crime, we can’t look at the cases or the people involved only as lawyers,” says Friel. “Sometimes we also have to be like social workers or counselors.”

Fueled by the same empathy she brought to her first rape case, Friel appears well suited to the demands of her job. Speaking of a recent prosecution of a serial rapist, she reflects on how her approach to victims has evolved from her initial kinship with the Penn graduate: “We had three complainants who could not have been less alike. One was a college girl who had gotten pregnant and was thrown out by her very religious mother. The second one grew up on Long Island, had kids and a job but then got hooked on crack and lost everything. The third one was a streetwise girl.

“I realized that to get the conviction I had to help the jury see them as people, not just as a wayward girl or a crack addict or a prostitute. And to do that, I had to see them that way.”

Victims’ AdVocAte Friel works out of the Criminal Courts Building in lower Manhattan, where she oversees a staff of about 50.

IRENE M. WIELAWSKI is a freelance journalist. She lives in Pound Ridge, New York.

"SHE'S A PIT BULL WHEN IT COMES TO INVESTIGATIONS."

"CASES ARE AWLWAYS MORE COMPLICATED THAN SIMPLY GETTING THE FACTS...SOMETIMES DAs ALSO HAVE TO BE SOCIAL WORKERS OR COUNSELORS."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July | August 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Feature

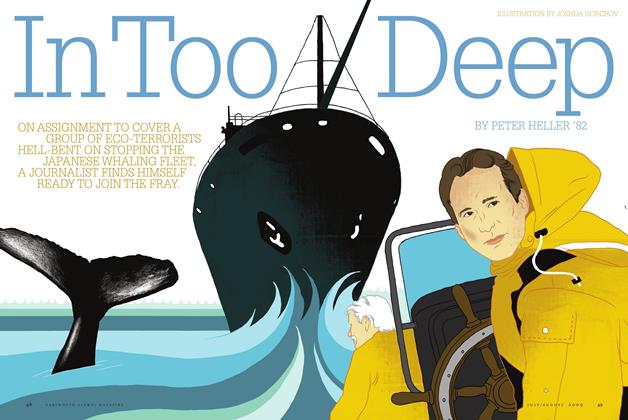

FeatureIn Too Deep

July | August 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

OUTSIDE

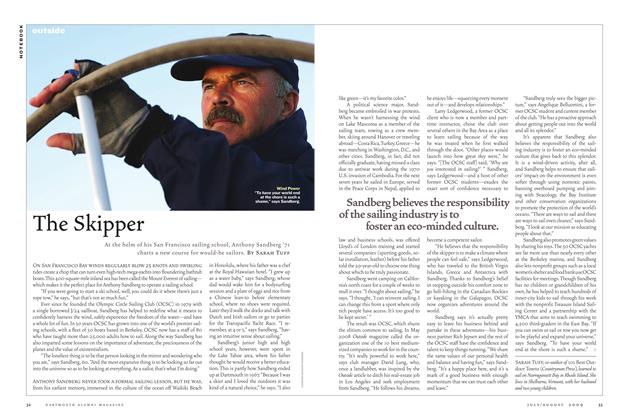

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July | August 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FILM

FILMLife’s Big Questions

July | August 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONTime for a Bigger Tent

July | August 2009 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu ’71

Irene M. Wielawski

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

Mar/Apr 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

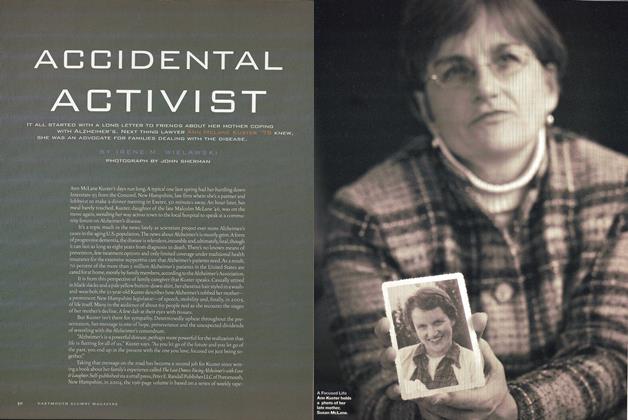

FeatureAccidental Activist

May/June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

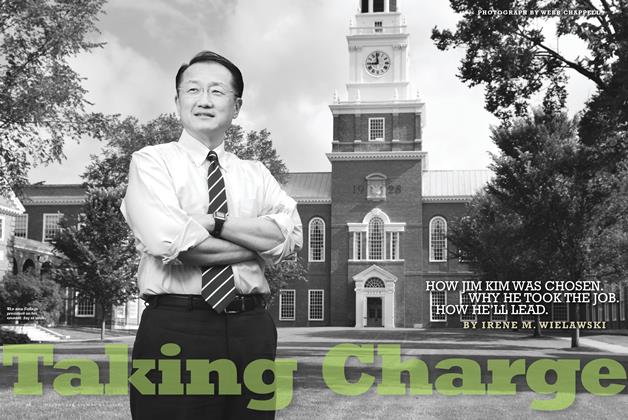

COVER STORY

COVER STORYTaking Charge

Sept/Oct 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJim Kim

Jan/Feb 2012 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs Your Brain to Blame?

Nov - Dec By Irene M. Wielawski -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBThe Future of Cancer

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By Irene M. Wielawski