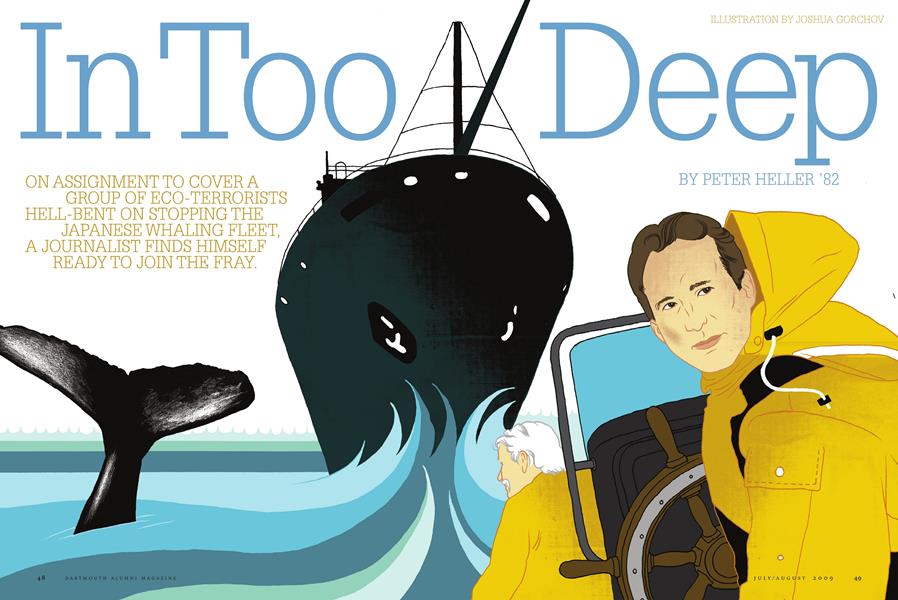

In Too Deep

On assignment to cover a group of eco-terrorists hell-bent on stopping the Japanese whaling fleet, a journalist finds himself ready to join the fray.

July/Aug 2009 PETER HELLER ’82On assignment to cover a group of eco-terrorists hell-bent on stopping the Japanese whaling fleet, a journalist finds himself ready to join the fray.

July/Aug 2009 PETER HELLER ’82ON ASSIGNMENT TO COVER A GROUP OF ECO-TERRORISTS HELL-BENT ON STOPPING THE JAPANESE WHALING FLEET, A JOURNALIST FINDS HIMSELF READY TO JOIN THE FRAY.

A little after 3 a.m.

on Christmas 2005 the all-black eco-pirate ship Farley Mowat smashed into a trough, took green water over her bow, then lunged wildly into a featureless sky. The first mate held tightly to the radar console and snapped at the bosun: “Tell the crew collision in two minutes.” We were 200 miles from the ice edge of Antarctica in a force 8 gale. The timberwork of the bridge groaned and creaked. The wind battered the thick windows and ripped past the superstructure with a buffeted keening. It tattered the Jolly Roger on the bow. Just ahead through a tearing fog we could make out the monstrous black stern and the block white letters Nisshin Maru: the 430-foot factory ship of the Japanese whaling fleet. Our captain, Paul Watson, had just given the order to ram and disable her. In these seas it was insane.

Go, I thought. You’ve got the speed, do it now. I surprised myself. I was on assignment for National Geographic Adventure magazine. Every journalist wants a better story, but this enthusiasm was something different.

Before I left the States my editor had said, “You can’t go native on this. If you become an eco-terrorist it will reflect badly on the magazine.” He meant that I shouldn’t get too close to the story and become partial.

The Japanese were planning to take more than a thousand minke whales out of the internationally established Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary, in spite of a moratorium on all commercial whaling laid down by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1986. This year they were also planning to take 10 critically endangered fin whales. One fin could bring in more than $1 million at market. The Japanese exploited a loophole in the whaling ban that allowed quotas for scientific research. The Nisshin Maru, which processed the whale meat, had “RESEARCH” painted along her hull in giant letters. The official line was that whales needed to be killed to study diet, age, stock structure, etc.—in order to preserve them. But the scientific committee of the IWC had raised no less than 20 objections to the kill program, saying the Japanese research lacked rigor and would not meet the standards of peer review.

The killing of a whale by most modern methods is cruel. An exploding harpoon meant to kill rarely does more than rupture the whale’s organs: The animal thrashes and gushes blood and begins to drown in its own hemorrhage. In an attempt to hasten the kill, the whale is then winched to the side of the ship, an electrical lance is jabbed into its side and thousands of volts are run through its body. The whale screams and cries and thrashes. Often, if it is a mother, its calf swims wildly around her, doomed to its own slow death later on. The electricity fails to kill the whale, and it can take another 15 to 20 minutes for it to drown and die. Whatever one thinks of whales’ high intelligence, advanced social structures, obvious emotions and still-mysterious ability to communicate over long distances, no one could defend this method of slaughter as humane.

For Watson and his crew of 43 that was enough. If no government had the political will to enforce the laws, they would. By Christmas I had been on the ship for three weeks, in ice and storm, while it pursued the whalers, and it now seemed I was supporting the mission. At least in general terms. Was I losing my journalistic integrity?

I had always wondered how photographers could take those shots: a starving woman lying in a Somali hut, one lusterless eye looking at the camera while her baby cried against her side—how could they take the picture and not reach out and feed the woman, rescue the baby? Or, in war reporting, what kept the journalist embedded in his own country’s army from grabbing a gun when his squad was about to be overrun? Journalistic mores require that you stay out of it. Document and move on. Was there a higher ethic than the professional code? The questions haunted me.

I first met Watson at the Telluride Mountain Film Festival in Colorado. I had moved west after graduating from Dartmouth. I had always known that I wanted to write about nature and the outdoors, so in Hanover I studied English and comp lit and took a lot of classes with the biology department. Down at the Ledyard Canoe Club I learned to white-water kayak, and it changed my life. After college I participated in river expeditions around the world, and my first articles for major magazines were about these trips.

“I’ve sunk half the norwegian whaling fleet and half the Spanish.” That’s the first thing Watson said to me. I had heard of him. He was the founder of the radical environmental group Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. He had helped found Greenpeace in 1972, then broken away five years later because he thought they were wimps. He did not want to wave banners or protest anymore, he wanted to go out on the high seas and physically intervene to stop illegal whaling and fishing. He wanted to enforce international conservation law.

He did. During the next 30 years he turned his ships into weapons and rammed and damaged illegal driftnetters and longliners. He blockaded the Canadian sealing fleet at the harbor entrance to the Port of St. John’s in Newfoundland in 1983. He faced down the Soviet navy—only the miraculous appearance of a surfacing gray whale between the two ships prevented him and his crew from being machinegunned into the Bering Sea. The Norwegian navy had depth-charged and badly damaged his last ship, and he had responded by hitting their Zodiacs with cannon loads of custard pudding. He led campaigns to protect the Galapagos and Grand Banks from poachers.

And he had sunk eight whaling ships to the bottom of the sea. His teams snuck into ports, searched the vessels, then opened the sea cocks or blew open the hulls with limpet mines.

Illegal fishing boats and massive whalers around the world knew he meant business and fled when they saw his all-black ship with its Jolly Roger come over the horizon. But he was proud of the fact that he’d never injured or killed anyone.

In Telluride the day after we met, Watson stood in front of a thousand people and said that the ocean was dying. He said half the coral reefs were dead or dying and that they harbor a million species. He said that of 17 global fishing hotspots like the Grand Banks, 16 have collapsed beyond repair. He said there are now only 10 percent of the fish stocks that were in the ocean in 1950. He said we should stop, every one of us, eating all fish. There was an uncomfortable stirring in the crowd.

“I don’t give a damn what you think of me,” he thundered. “My clients are the whales and the fish and the seals. If you can find me one whale that disagrees with what we’re doing, we might reconsider.”

It was a powerful message. The stakes seemed very high. In light of this extremity—the rapidly unraveling ecosphere—he would take extreme action.

There is no doubt Watson transgresses the law. In 2002, testifying before a congressional committee, James F. Jarboe, domestic terrorism section chief for the FBI, listed Sea Shepherd as an eco-terrorist organization. He defined eco-terrorism as “the use or threatened use of violence of a criminal nature against innocent victims or property by an environmentally oriented, subnational group for environmental-political reasons, aimed at an audience beyond the target, often of a symbolic nature.” Piracy, as defined by the Law of the Sea, includes: “Any illegal acts of violence…by the crew or passengers of a private ship…on the high seas, against another ship…or against persons or property on board such ship….”

Under these definitions I would be sailing under the command of a terrorist and a pirate. (Watson counters that he only damages property used in illegal activities, and that if he were a terrorist he wouldn’t be given 501c3 nonprofit status by the IRS or allowed to dock at his home port in Washington State.)

Before I left for Australia and the ship, my editors at Adventure had Watson sign a letter acknowledging that I was a journalist on assignment and not a participant in any way. I have to admit that the letter gave me some comfort. I had a copy of it laminated, figuring that if we were sunk by the Japanese—which we nearly were, twice—or arrested the letter might spare me some time in the brig, where I was sure I would be fed whale meat twice a day.

When I got to Melbourne I was taken aback by my first sight of the Farley Mowat. She looked like a ship of war. She bristled with water cannons to prevent boarding. Her bow was a black bludgeon. And a few days later, just south of Tasmania, the engineers came on deck and welded a giant blade called the Can Opener to the starboard bow. It was then I knew for certain that this assignment was not a lark.

At first I was very careful not to “participate” in any way. If heavy blocks had to be moved on deck, I stepped aside, which felt unnatural. When Watson confided in me that he had used the international press to disseminate misinformation, I just blinked and wrote it down. He had told Australian interviewers that he was heading south and west, but he told me he would actually trend eastward to search for the Japanese fleet near the Ross Sea.

I got to know the crew. They hailed from Canada and New Zealand, Holland and France and Australia. There was a Hell’s Angel tattoo artist, a Hollywood producer, an international environmental consultant and three professional gamblers from Syracuse who ran a Texas Hold ’em game in the mess every night. The chief cook was a young woman from Australia who was a champion endurance rider. What they all had in common was a commitment to stop whaling in its tracks. At all costs. Every one of them would die to save a whale. Most of them had heard Watson speak somewhere and it was the purity of his message that had struck home: You protect the species that can’t protect themselves because it’s the right thing to do. Period.

Within a few weeks I was helping the crew move stuff. I was one of the few on the ship with a good dry suit, so I took a mask and flippers and volunteered to be the rescue swimmer during an engagement.

One calm morning I stepped out on deck and saw a plume of mist just off the starboard bow, and another, smaller jet. A white-mottled long fin gestured out of the water and the two glossy dark backs, mother and calf, dove under the boat, the mother’s articulated, graceful fluke disappearing last. Farther off starboard were three more blows, the hot mist trailing gently downwind. Behind them were more and more. Spouts of steam rising and drifting. I stared, almost stricken. All the way to the horizon, where two flattop icebergs marked the edge of the world, were humpback whales swimming slowly east. Pairs and small groups rolled around each other, showing fins, flukes, eyes, and then moved on. They swam past the boat on both sides. Hundreds of whales. Could they be swimming away from their hunters in the quadrant to the west? They were not on the Japanese quotas until next season, but no sizable whale was safe down here. They were not concerned with us at all. I tried to imagine the migration generations earlier, when they weren’t a fragmented, isolated population, when their numbers were fifty to a hundred times what they are today.

I was reading more about the crisis of fisheries and seabird populations around the world. I learned that an area twice the size of the United States is bottom trawled every year, which essentially turns the benthic community—the bottom reefs and grass beds—into parking lots, and that once the catch is hauled in, 20 to 80 percent of the dying animals are tossed overboard as “by-catch.” This struck me as beyond a crime of waste, it seemed a terrible sin. I learned that oceans are more acidic than they’ve been in 650,000 years. I also learned in e-mails from Sylvia Earle, the great oceanographer, that the oceans supply more than half of the world’s oxygen, that they balance the planet’s temperature.

I grew up with Jacques Cousteau, with the sense that the oceans were almost endlessly vast and teeming and exuberant with life. It is no longer true. We are in the grips of a mass extinction the likes of which hasn’t been seen in 65 million years.

I came to hope that Watson succeeded: I wanted him to stop the bottom trawlers and whalers where he could. The stakes are just too high. We are losing species and habitat so fast nobody can predict how long the oceans can maintain even a semblance of vitality. A report published in Science in November 2006 concludes that if current trends continue every fishery in the world will be in collapse by 2048. It’s staggering to think about.

Did I agree with Watson’s methods? I was torn. I did not believe violence was ever the best solution to anything. He hadn’t hurt anybody yet. As long as that continued I could support him. Was it violence to damage the weapons used illegally against wildlife? Or was it like trying to silence gun batteries that were shelling innocent populations?

After the hair-raising encounter Christmas morning, in which the Farley was almost t-boned and sunk, we engaged the whalers three more times. Watson rammed a big tender ship with the Can Opener and sent it running back to Japan. He chased the Japanese so far west along the ice edge that we passed the point of no return—with not enough fuel to make it back to Melbourne. We hit storm after storm and after two months at sea made it to Cape Town with a day’s worth of fuel in the tanks. The whalers returned to Japan 84 whales shy of their quota—and badly damaged by the international press attracted to Watson’s actions. Just after we got home the five major Japanese fish companies that owned the whaling fleet divested their holdings, citing “poor consumer demand.”

Home now on dry land, safe from gales and counter-attacking Japanese ships, I haven’t resolved any of these questions. Except that I know, I know we should not be killing whales. Or dumping 40 million tons a year of mortally injured wild animals back into the sea as bycatch. For me it’s not about animal rights. I hunt and eat meat. It’s just sound conservation. And I am glad that there is a broad spectrum of approaches in the environmental movement. On one side are the National Resources Defense Councils and World Wildlife Funds, the NGOs that work primarily with governments, with policy and legislatures. And on the other end of the spectrum is Greenpeace, and beyond it, Sea Shepherd.

In ships, out on the high seas, they force the issue and make us look at the horror of our overexploitation. As long as nobody is harmed it seems to me the issue needs to be forced. If our ecosphere dies all other issues will be moot.

Sea Change “After what I saw, I couldn’t stop thinking about the crisis of the oceans, how they are on the verge of collapse,” says Heller. “I wanted to be closer to the sea.”

PETER HELLER is the author of The Whale Warriors: The Battle at the Bottom of the World to Save the Planet’s Largest Mammals. He lives in Denver with his

“watson hadn’t hurt anybody yet. as long as that continued I could support him.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

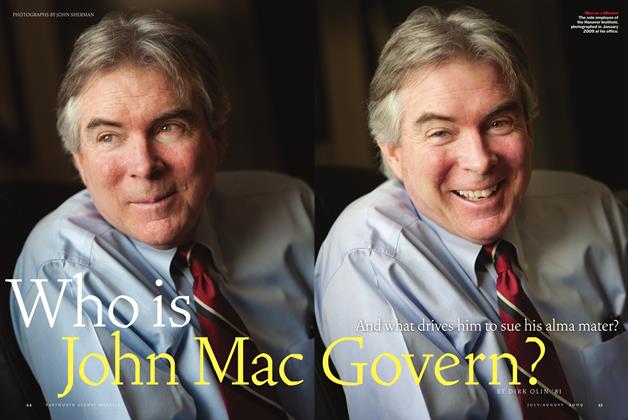

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July | August 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

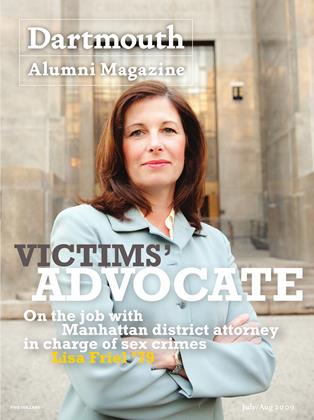

Cover Story

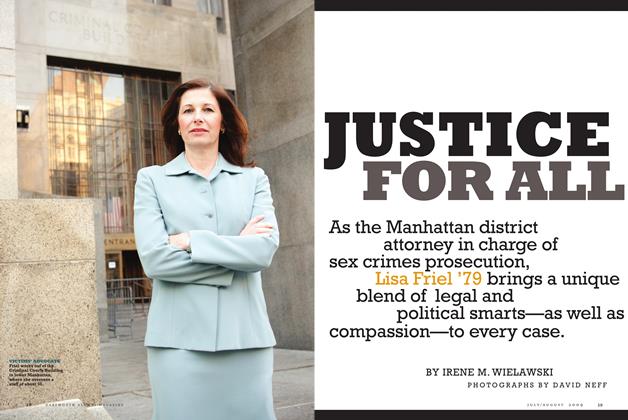

Cover StoryJustice for All

July | August 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July | August 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FILM

FILMLife’s Big Questions

July | August 2009 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONTime for a Bigger Tent

July | August 2009 By Ed Gray ’67, Tu ’71

PETER HELLER ’82

Features

-

Feature

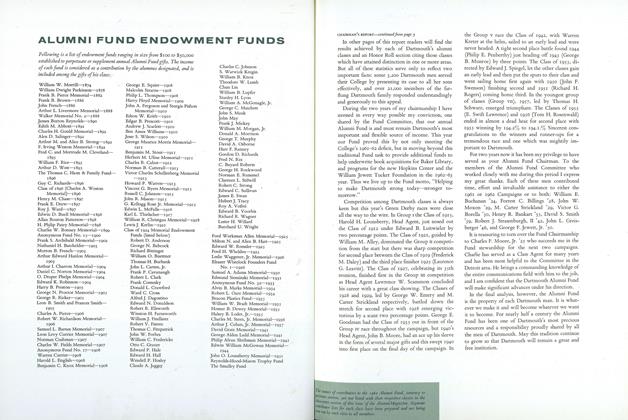

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

Feature2. Drinking

December 1987 -

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

FEATURE

FEATURERemnants of a Moment

MAY | JUNE 2016 By GAYNE KALUSTIAN ’17 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Clean Air?

JUNE 1971 By Robert B. Graham '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch