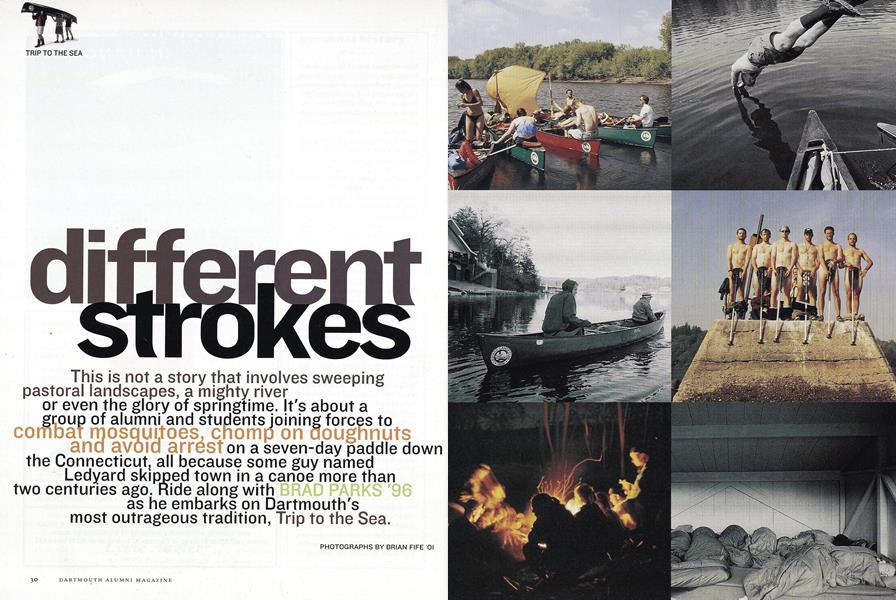

Different Strokes

This is not a story that involves sweeping pastoral landscapes, a mighty river or even the glory of springtime. It’s about a group of alumni and students joining forces to combat mosquitoes, chomp on doughnuts on a seven-day paddle down the Connecticut, all because some guy named Ledyard skipped town in a canoe more than two centuries ago.

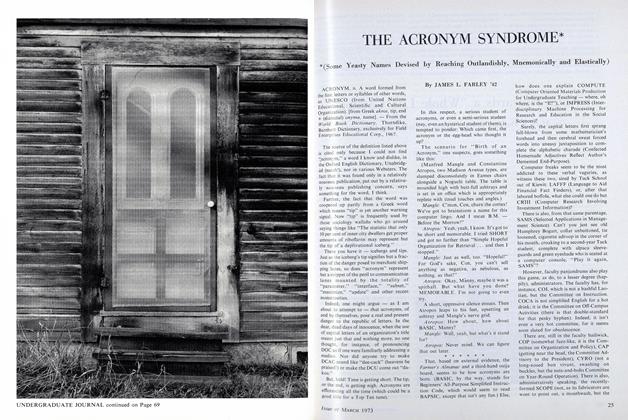

May/June 2002 Brad Parks ’96This is not a story that involves sweeping pastoral landscapes, a mighty river or even the glory of springtime. It’s about a group of alumni and students joining forces to combat mosquitoes, chomp on doughnuts on a seven-day paddle down the Connecticut, all because some guy named Ledyard skipped town in a canoe more than two centuries ago.

May/June 2002 Brad Parks ’96This is not a story that involves sweeping pastoral landscapes, a mighty river or even the glory of springtime. It's about a group of alumni and students joining forces to combat mosquitoes, chomp on doughnuts on a seven-day paddle down the Connecticut, all because some guy named Ledyard skipped town in a canoe more than two centuries ago. Ride along with as he embarks on Dartmouth's most outrageous tradition, Trip to the Sea.

There is no way

I realize immediately, that I'm going to remember all these names. I also realize I don't have a choice. Because whereas Dartmouth alums long ago gave up trying to remember and now just wear name tags, Dartmouth undergrads have not yet surrendered to their amnesia.

So here I am on a Sunday morning in early May, shivering near the frost-covered docks at Ledyard Canoe Club, forgetting names at a furious pace. One of our trip leaders, Rob Hallenbeck '01, has asked us to go around the circle, say our name and class year, and share why we're going on Trip to the Sea, a 220-mile paddle down the Connecticut River. Having contemplated his answer in advance, Rob starts with a thoughtful statement about how he hopes the conversations he has on the trip will lead him to find fulfillment and happiness in his life after graduation. Being a typical college senior, he figures this should take him about a week.

The rest of us are somewhat less profound. One woman—what was her name again?—wants to "freak out my thesis advisor." Another guy, a recent alum, I think, is out of work and has nothing better to do. As my turn in the circle comes, I have this slight sense of dread. I always think of what I really want to say about five minutes too late, which is why I'm a writer. I could talk about being linked in spirit and deed to generations of Dartmouth men and women before me, or about how I could use some time away from my girlfriend to figure out if I want to spend the rest of my life with her. Being a typical 26-year-old, I figure this will take, at minimum, 10 years.

But when my turn comes I mutter something about how I always wanted to go on Trip to the Sea as an undergrad but never got the chance, and because it beats sitting in an office for a week. Frankly this is a bunch of crap, because all I'm really thinking, but do not quite have the courage to say, is: "My name is Brad Parks. I'm a '96. I'm standing in a circle with 11 strangers whose names I cannot remember, and in five days we're going to get naked."

Roughly 20 steps from where I'm standing is a plaque that provides a brief history of Trip to the Sea. It describes the epic journey of John Ledyard, a freshman in 1772, who was so fond of his first winter in New Hampshire that he felled a mighty birch tree, carved a dugout canoe and skipped town as soon as the river thawed—a kind of 18th-century spring break road trip down the Connecticut River to Long Island Sound.

And every year for the past half century, Dartmouth students have retraced Ledyard's journey. The most appreciable differences between Ledyard's trip and ours is that our canoes are made of Kevlar (no doubt chiseled from a mighty plastic tree) and the majority of our trip planning was done over e-mail.

From the flurry of messages preceding our trip, I had learned, to my surprise, that I was going to be the oldest person in the group. The Ledyard Canoe Club invites alums on this trip, and typically you would expect to be joined by a few alums from the 19605, 19705, 1980s—you know, some old farts trying to cling to their faded youth. Instead, I am that desperate, flatulent hanger-on.

Not that it's an issue, I tell myself as we haul the canoes onto the dock. Five years does not a generation gap make. What's the big deal?

"Hi," I say to the apple-cheeked brunette who arrives shortly after the introductions. "My names Brad."

"Oh," she replies cheerfully, "so you're the old guy! I heard there was an old guy on the trip."

She tells me her name is Chris Campbell '01, then looks at me with concerned eyes, perhaps sensing she has damaged my male ego. "Oh, don't worry," she adds. "You're not that old."

Chris tells me why she was late: She had been drinking beer and playing pong in the Sigma Nu basement until 3 a.m., had gone home and slept for an hour, then woke up and packed. Now she is scooting around preparing to get on the water with no apparent loss of vitality. I, on the other hand, had gone to sleep at 10:30, sober as a judge at a hanging, but still feel like I am walking around with a canoe strapped behind me.

Maybe, I think to myself, I really am that old.

By the time we get under way, the sun is rising over the ridge, illuminating the swollen leaf buds that weigh heavily on the trees. Our six canoes slip silently across the water as the sunlight begins to reveal a perfectly splendid May morning in New Hampshire. Why, I think to myself, would John Ledyard ever want to leave this?

Then again, this isn't going to be seven days of musing about the trees, rocks and weeds of New England. Another Dartmouth guy, name of Frost, beat that subject to death already.

This is about a dozen people'who won't change their underwear for a week.

gasp for air punctuated by occasional grunts) is loud enough to create an echo when we paddle through valleys; Brooke Lierman'01 who strikes me as the type who will run for Congress some-day—and win; Mark Kutolowski '99, a vegan who is considering ing becoming a monk; Emily Horrell '02, a farm girl/engineering major from the hills of North Carolina; Karyn Brudnicki '01, who somehow manages to reconcile her fun-loving side with serving on the Colleges student disciplinary body; Adrian Loehwing '01, a quiet type who writes in a diary every night; Paul Nicklas '01, one of our co-leaders, whose range of interests span everything from ancient weaponry to white-water kayaking; Dori Sugar '01, who finds out I write for a newspaper and observes, "Newspapers waste a lot of paper"; Jocelyn Leavitt '01, with the beautiful singing voice, who joins the group late on the first day; and Brian Fife '01, a combination goofball/philosopher who is serving as the trip's photographer. On a trip like this, when it's just you, a canoe paddle and a stretch of water that won't be ending soon, it doesn't take long for the personalities to emerge. There is Chris, the spunky senior from Alabama; co-leader Rob, as genuinely nice a guy as you'll meet; Ben Guaraldi '99, whose laugh (really a desperate

As we raft up and let the brisk current carry us through the afternoon, I start learning new things about my alma mater, the kind of things that somehow don't get mentioned in President Wright's letters—about the chlamydia outbreak in the freshman class that fall, what it means to be "sexiled" (kicked out of your room while your roommate gets intimate) and the news about the boyfriend who was stupid enough to write about his girlfriend (uh, ex-girl-friend) in the controversial Zeta Psi newsletter.

Our conversations—like whether "George Clooney" is the funniest name ever uttered—meander until mid-way through the afternoon, when Chris asks, "Why do they call this 'Strip to the Sea?'" This begins our first talk about the subject, when the trip veterans explain our duty in upholding Trip to the Sea's most cherished tradition: paddling naked through Hartford on Friday. Of course, most of the discussion centers around Brian, who has brought 45 rolls of film and plans to exhaust as many of them as he can on that day. Brian instantly becomes the guy you don't want to piss off.

The next morning begins as all our mornings on this trip will, with Mark playing a small Native American wind flute. He only knows a few tunes, but it rates high as alarm clocks go, especially at 6 a.m. It still takes a major act of will to climb out of a warm sleeping bag and into the frost-covered world, but we all manage eventually—last of all Rob, who, incidentally, snores like a lumberjack.

We bumble around camp, still unfamiliar with our gear and each other, so it takes forever to get on the water. After as much delay as any Type-A person can reasonably stand, I'm finally in a canoe with Karyn and Chris—with Jocelyn's arrival our numbers necessitate a three-person canoe—talking about, of all things, my girlfriend, Melissa. I tell the story of how we met in August during our sophomore summer.

Karyn and Chris quickly do the math: seven years. We've been dating seven years. They are instantly incredulous.

"So why haven't you asked her to marry you yet?" Karyn says.

"Yeah, dude," Chris chimes in, "what's your problem?"

I try to explain that it's complicated, that seven years can just sort of flit by, that marriage is not something to, you know, rush into. "After all," I say, "if it's 'till death do us part,' what's the hurry?" They are unmoved.

"You love her, don't you?" Chris asks.

"Of course," I say.

"Then, dude," Chris says, "what's your problem?"

This forces me to resort to the Underwear Monologue. It's something I read in a play a few years back about a guy who is terrified of marriage. He enjoys discovering what kind of underwear a woman wears. But if he gets married, he'll be stuck with one woman's arsenal of underwear forever. How could he bear that?

"That's easy," Karyn says. "Just go out and buy her more underwear."

Later that night, over a campfire at our Night 2 campsite, the subject comes up again. Thankfully I'm not at the center of the conversation, and this time monogamy is taking a kick in the tail, as a high-pitched voice in the darkness opines, "Men are like ice cream. You don't want to have one flavor the rest of your life."

This (somehow) morphs into a conversation about why we've been put on this Earth, what we're supposed to accomplish here, what life is about. I offer a theory I've been kicking around lately: "To me, life is about having great stories to tell. Love stories, adventure stories, funny stories, whatever. You can tell a story about anything worthwhile that happens in your life, so a life with a lot of stories is a good life."

For a moment, there's silence. Brooke, never one to miss a good argument, can't let it pass. "No. I think that's full of crap. Life isn't stories. It's about moments, and the feelings you have in those moments."

Paul says, "Physicists would say the world we experience is really just a series of moments. That we think they happen in some order, like a story, is an accident of our human senses."

But Brooke isn't finished. "Like if I'm sitting in bed one Sunday morning and life is great and everything is going well and I'm just enjoying a few more minutes of closing my eyes savoring that. That's a great moment. But you can't tell a story about that."

Me: "You just did."

Silence. Then another voice in the darkness: 'Anyone ever tried to eat pine pitch? I hear it's just like chewing gum."

From a physical Standpoint, the first two days are relatively easy, or at least as easy as 70 miles plus a couple of portages can be. That changes abruptly on Day 3. Around mid-morning we switch canoes when Paul pulls a shoulder muscle. He ends up as the third man with Adrian and me, which seems fine at first. But then the current stops because we're approaching a closed dam. Ahead wind kicks up. And we're in for paddling hell with 180 pounds of dead weight in the middle of the canoe.

Battling a strong headwind in a canoe is a lot like trying to run out to the store on a treadmill: You feel like you're busting a lung, but no matter how hard you work, you're still not moving anywhere. As we approach a railroad bridge in the middle of the river, I close my eyes and pull as hard as I can: 20 strokes, 30 strokes, all full speed. My shoulders burn. My heart pounds. Surely, I think, by the time I open my eyes, we will have made significant progress. Then I take a peek. And we're in the same place.

But that's not as bad as when we stop paddling for a moment, because then we go backward.

Canoes don't have odometers, of course. Not that it matters, because we don't have a map. They're considered unnecessary because the trip leaders have been on the trip before and (supposedly) know where we're heading, and because it's not like you can make a wrong turn on the Connecticut River. The problem with this is we never know exactly know how far we've gone, or how far we have to go.

At 11:30 I ask Paul how much further to the blasted dam and he says, "It's less than an hour from here."

At 1:30 I ask Paul how much further to this God-forsaken, mother-hating, beaver-loving dam and he says, "It's less than an hour from here."

We finally reach the dam at 3:30, less than an hour after I feel like throwing Paul overboard.

The next morning our motivation for getting out of bed, for skipping breakfast and for hurrying away from camp is a simple one: We've got doughnuts waiting for us. It's become a venerated Trip to the Sea tradition that on Day 4, Art Ruggles '37 meets the trip at its first portage spot with a load of doughnuts. And after four days of subsisting on oatmeal, couscous and peanut-butter pitas, the thought of slipping a fat, juicy, glazed doughnut into your mouth can inspire great things.

We take advantage of the quiet, flat conditions during our first 10 miles of paddling to stay in tight formation and sing about, what else, doughnuts. No one has written an "Ode to Doughnuts"—an oversight by the world's great composers, to be sure—so we create them as we go, using the word "doughnut" where appropriate ("The hills are alive, with the sound of doughnuts...").

We also mix in choruses of the "Paddle-a-Canoe Song," which is sung to the tune of "Sh-boom," but with verses that are made up on the fly, such as: "There was a group paddling through Hartford/They get buck naked, or that's the word/They don't wear cotton, wool or fleece/They have to go fast to avoid the police."

We land at Doughnut Beach and immediately make like Discovery Channel hyenas around the pile of Krispy Kremes laid out for us. As we gorge ourselves, we are greeted by Ruggles, a kindly octogenarian who says he has a house nearby and, If the girls want to wash up, the boys can unload the canoes."

The "girls" think this is rather amusing. Some of them have regularly been carrying twice as much on the portages, as the boys, like farm-girl Emily, who may look like a fair-haired, petite "college girl" but can give a pack horse a run for its money. Perhaps in a different environment, the "girls" would rail at this assumption of their inherent weakness and insist on pitching in equally. However, at this point in the trip, loading and unloading canoes has lost any allure it once had. Being pressed into genderized roles by a patriarchal figure suddenly doesn't seem so bad. They smile sweetly

The moment of No Return, when we officially lose all inhibitions around each other, comes later that afternoon. We are floating in the middle of the Connecticut River, our canoes joined together for an afternoon snack break, when Mark decides to relieve himself. He stands up, turns around and lets fly off the back of his canoe. Rob and Paul think this is a swell idea and quickly do the same. And from that point on, it becomes a fairly regular occurrence to see someone relieving himself—or herself—off the end of a canoe. We're all friends, we decide. Woe to all those downstream.

Besides, we're feeling good. The weather, once again, is perfect who would have thought our toughest challenge from the elements on a trip like this is just to get enough suntan lotion on? And we have a tailwind pushing us downriver for once.

The good mood and good fortune last clear to the end of the next day, right up until it comes time to find our landing spot, which always seems a little more difficult than it needs to be. We are looking for the Loomis Chafee School in Windsor, Connecticut, where we will be crashing on the floor of the gymnasium. We make a right turn up a tributary, paddle upstream and begin our usual aimless groping. Paul points to a small clearing on the bank wide enough for only one canoe and says, "I think that's it."

Ben and I are the first to reach the spot. I disembark and immediately feel mud oozing around my ankle. "Paul, this can't be it," I say. As he assures me it is, I feel a small prick on my neck. Then another. Then a bunch. And suddenly it dawns on me I'm in the middle of a swarm of mosquitoes, it's feeding time and I'm dinner. "Paul, this just can't be it," I say, swatting furiously. "No," he says, "this is it."

Ben gets out and sinks his Tevas in the slop. We pull our canoe up the bank, instantly turning the landing area into a slippery quagmire and rendering it unusable for anything besides mud wrestling. The other boats pile up behind us, not that there's anywhere for them to go, and the increase of human flesh in the area only sends more mosquitoes dive-bombing down on us in attack formation.

We change strategies and pull the canoes up the steep sides of the riverbank, which begins what is easily the worst 15 minutes of the trip. It is 15 minutes of swatting, swearing, slipping, tripping, swearing, sweating, hauling, swatting and swearing until somehow, through the chaos, we manage to get all the canoes out of the river, get our gear away from the canoes and get our bodies away from the feasting mosquitos.

But just as quickly as it begins, it ends. The Loomis Chafee gym has mens and women's locker rooms, each with showers. Before long, the guys are suds-covered and laughing and someone—Ben, I think—leads us in crooning, "I'm siiiinging in the raaaiin." A skinny, bad-complexioned Loomis Chafee lad, probably a freshman, wanders by as we start the second chorus. He quickly turns back, however, and leaves the area. Seven naked men, sharing soap in a communal shower, singing show tunes? This has to be what Mother warned him about.

That evening at dinner, while idly scratching dime-sized mosquito-bite welts, we discuss our duties in Hartford the next day. Paul doesn't bother with any kind of pep talk about the necessity of our mission. No one wants us to be remembered as the prudes who went through Hartford with their jockeys locked in the full upright position. "It's just between two bridges," Paul explains. "It's only about a quarter of a mile. It's no big deal. You don't have to do it if you don't want to, but usually everyone does." The words have barely escaped Paul's lips when Adrian cuts him off.

"I haven't even let my boyfriend see me naked," she says nervously. "I'm not going to let you guys see me."

That's where the discussion ends until the next morning, the fateful Day 6. We breakfast in the Loomis Chafee dining hall, in the midst of some high school kids who are eyeing us suspiciously, including the aforementioned freshman, who, I swear, walks by just as someone utters the phrase "group nudity."

Over breakfast we pair off into what will become our designated canoes for the indecent dash—Jocelyn and Nick Koshnick '01, who replaced Dori on the trip a few days earlier, form our only coed canoe; Karyn and Chris, mischievous pair that they are, share another; Adrian and Emily are in a third. That leaves the guys: Mark and Ben, Rob and Brian, Paul and me. We're ready.

We come across our first bridge early, with my canoe in the lead. "That the bridge?" I ask as I get ready to lower my shorts. Paul looks stricken for a moment, then says, "No, not that bridge." Indeed, we're still several miles outside Hartford. After another half hour of paddling, Paul points to a stone bridge in the distance and yells: "That's it, guys."

Sure enough, the Hartford skyline looms before us. I can see the state capitol dome where, as a fully clothed school child growing up in Connecticut, I visited on field trips. I can see the Marriott Hotel where, as a fully clothed journalist, I stay when I cover UConn games. I can even see a building-sized mural of two basketball players I had once interviewed—again, clothed.

"Paul," I say, "I think this is going to be one of those moments in my life I never forget."

He grins. As we wait for the other canoes to catch up, he tells me about the previous year's group, which was accosted by river police all of three minutes after it had re-robed. It was the general opinion of that group—and this one, no doubt—that an indecent exposure charge would be an inopportune thing for a college senior to have to explain at a corporate recruiting interview.

Me? I think it would be hysterical. Talk about a great story to tell. Besides, I'm a sports writer. If my boss found out I was caught naked in broad daylight with half a dozen college-aged women, I'd probably get a raise.

Soon we are assembled under the cover (and temporary sanctuary) of the stone bridge. Paul repeats the two-bridges, quarter-of-a-mile pep talk, but Nick and Jocelyn are already in various stages of undress. So the time has come. I take off my shirt, loosen the drawstring around my shorts and hear myself counting down: "Three-two-one, drop 'em."

We emerge from the other side of the bridge, a blinding assemblage of pale backsides gleaming in the mid-morning sun, our paddles churning rapidly in the water, our pants around our ankles.

going to be paddling naked through a city in the middle of the day again, so we might as well enjoy the experience. Paul and I pull alongside Karyn and Chris and begin splashing them. Up ahead, Ben and Mark are hanging a full moon on Nick and Jocelyn, who quickly return fire, butt cheeks blazing. Then Paul and I moon Rob and Brian, who, I hope, did not capture that particular Kodak moment on one of his 45 rolls of film. After about 30 strokes at full steam, we start to slow up. I think it occurs to us more or less at the same time that we're probably never

For the first few minutes, no one on shore seems to notice. We had heard stories about leering construction workers on bridges. But our splashing, hollering and carrying on is happening in the middle of the river, where we're apparently a bit too indistinct for the smattering of fishermen several hundred yards away. Then we hear a loud "Woo hoo, woo hoo" from the other shoreline. We look over in time to see a man standing next to a brown Pontiac, naked except for his boots, twirling his shorts over his head.

By the time we reach the next bridge—our duty to alma mater complete, our quarter mile concluded—we decide, what the hell, might as well keep going. There's nothing that says we only have to go from bridge to bridge. We paddle on for another two miles, splashing each other occasionally, letting the sun warm our bodies. It's really quite pleasant, although I'm secretly disappointed there are no river police in sight.

Eventually we decide we've tempted fate enough, pull on our pants and raft our canoes together for a morning snack. With perfect timing, Chris, 01' apple cheeks herself, pulls a Granny Smith out of one of the bags, holds it alluringly and says: "Anyone care to sample the forbidden fruit?"

That night, after another long and back-busting battle with a strong headwind, we reach our last campsite and make a crucial decision. This lowest stretch of the Connecticut River is influenced by the tides, and we have learned low tide is going to be at 7 the next morning. That means if we get started at our usual hour, we're going to be paddling dead into an incoming tide—not to mention a headwind. But paddling at night will eliminate those obstacles.

So we wake at 3:30 and break down camp with quiet efficiency, packing the canoes by flashlight. The group that stumbled around bumping into each other that first morning can now function in darkness with no more interaction than "Can you get that water bottle?" or "Is that your knife?"

At a few minutes before 4, we slip away, our paddles dipping into the calm, flat river. There's something enchanting about paddling in a canoe at night. The river is different, more mysterious. The banks in the distance are dark, thoroughly beyond understanding. There is less to see and yet more to think about. My thoughts drift to my girlfriend. It's been a long time since I've gone a week without talking to her. I miss her. My mind replays the incredulous interrogation Chris and Karyn had given me a few days before. Why hadn't I asked her to marry me? Of course I love her. I wondered, as Chris so perfectly put it: Dude, what's your problem? Maybe it is that easy after all.

We paddle into dawn, rafting up just as the sun breaks the horizon so we can enjoy the sunrise together. An hour or two later, we find a concrete block in the middle of the river. It probably was used for tying up boats in a bygone era, but it seems the perfect place for a Men of Ledyard photo: Our own, all-nude, beefcake salute, with canoe paddles strategically placed so as not to embarrass our mothers. Not to be outdone, the women use paddles and life vests to cover their personal places and pose for a similar photo.

Around 10 we reach a yacht club, which serves as a breakfast/nap spot to get ready for our final paddle, seven miles that take us to the end of the Connecticut Rivers brackish water and into the saltwater of the Long Island Sound. It's not an easy go, what with the Saturday afternoon boat traffic, a decent chop and a gusty breeze. But as we approach a lighthouse that marks our final destination, I feel the kind of stirrings ancient ship captains must have felt at the end of long journey at sea (only without the scurvy or mutinous crew).

We round the final point and head for home paddling in formation, singing the alma mater, the "Paddle-A-Canoe Song" and every other goofy melody we thought up during the trip. When we reach land, we jump out of our canoes, hug each other, tackle each other and generally carry on like a bunch of fools who really have spent too much time in a canoe.

In a blur we load the canoes onto a van and trailer that are waiting for us, head to a local YMCA and emerge as new people, showered and freshly clothed. It feels good. It feels strange. Is it really over? Yes, it is. As we head toward a reception being hosted by the Southeastern Connecticut Dartmouth Club, the seniors start chattering about how they only have a month until graduation.

Once at the reception, with name tags firmly in place, part of our group splits off from the alums for an earnest discussion about life outside EBA's immediate delivery area. That ominous question—What Are You Going To Do After You Graduate?—has taken on a new urgency. And they've convinced themselves they have to figure it out Now, or they're some kind of failure. I decide not to tell them that five years after we wrung our hands through the spring of 1996, most of my classmates still don't have a clue.

"I've heard people say college is the best four years of your life, Paul says. "I really hope that's not true."

What I want to say is: "It's not, Paul. It's really not. If you're living right, every four years that go by are the best four years of your life."

Of course, I don't think of that for another five minutes. Sometimes I wish I weren't a writer.

Before long, we're back in a circle again, this time for the edification of the alumni. We go around, stating our names, our classes and what we enjoyed about Trip to the Sea. But this time, when my turn comes, I manage to say exactly what I'm feeling:

"My name is Brad Parks. I'm a '96.1 don't know where I can place this within my Dartmouth experience, because technically that ended five years ago. But if I can add a postscript, then this is one of the best things I did at Dartmouth."

The next day, we wake early—we're used to it now—load the van and begin the drive to Hanover. No longer strangers, we've achieved that immediate intimacy of people who have spent a lot of time around each other in a short period, and we're sharing private jokes that already seem years old.

Heading up on I-91, we get a glimpse of the Connecticut River every 15 minutes or so, crisscrossing it several times. The river that took a week to navigate in canoes, as John Ledyard once did, will take us only a few hours by car. And as we head north, we come to the conclusion there is really only one thing left to do:

Drive through Hartford naked.

BRAD PARKS is a sportswriter for The Newark Star-Ledger. Amazingly, he finally ashed Melissa Taylor '96 to marry him attheir fifth-year reunion last June, a month after he returned from Trip to the Sea. Evenmore amazingly, she said yes.

Birth of a Tradition Although originated by freshman John Ledyard in 1773, Trip to the Sea took about a 150-year hiatus until May 26,1921, when 13 Dartmouth students, members of the recently formed Ledyard Canoe Club, left Hanover and paddled to the Long Island Sound. Trip to the Sea's early history is sporadic. There is no record of any trip between 1936 and 1954, when the Depression, a world war and river pollution conspired to halt the tradition. But in spring 1955, six undergraduates revived the trip. It began as a race—Peter Knight '62 and Jon Fairbank '62 set what is still the record when they completed the trip in 33 hours and 50 minutes—but evolved into more of a pleasure cruise. Now the seven-day trip leaves from the docks of Ledyard Canoe Club each May with anywhere from eight to 30 undergraduates and alumni. Through the years trip participants have survived illness, foul weather, food poisoning, nights in jail, flooding and more blisters than the Oxford rowing team.

As we raft up, I start learning new things about my the kind of things that somehow don't get mentioned in President Wright's letters.

We land at Doughnut Beach and immediatelymake like Discovery Channel hyenas around the pileof Krispy Kremes laid out for us.

We near a loud"Woo hoo, woo hoo" from the other shoreline and look overto see a man naked except for hisboots, twirling his shorts over his head.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsThe Tao of Cha

May | June 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryOut of Bounds

May | June 2002 By Sarah Lang Sponheim ’79 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

May | June 2002 -

Article

ArticleFalse Sense of Security

May | June 2002 By Professor Allan C. Stam -

Article

ArticleThe Gift of Education

May | June 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

May | June 2002 By Nihad M. Farooq

Brad Parks ’96

-

Feature

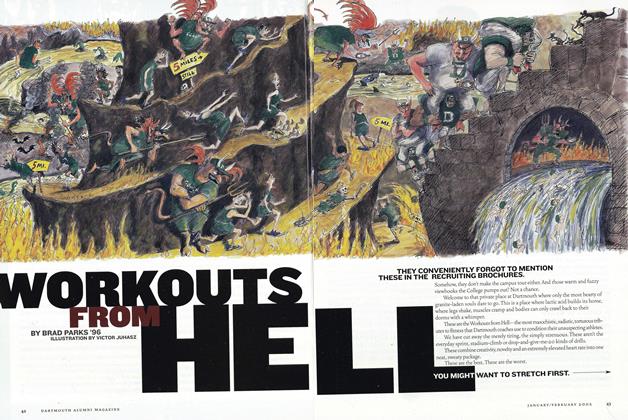

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Sports

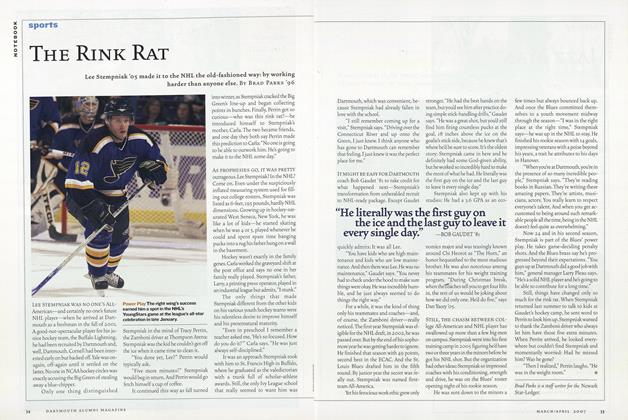

SportsThe Rink Rat

Mar/Apr 2007 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

SPORTS

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May/June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

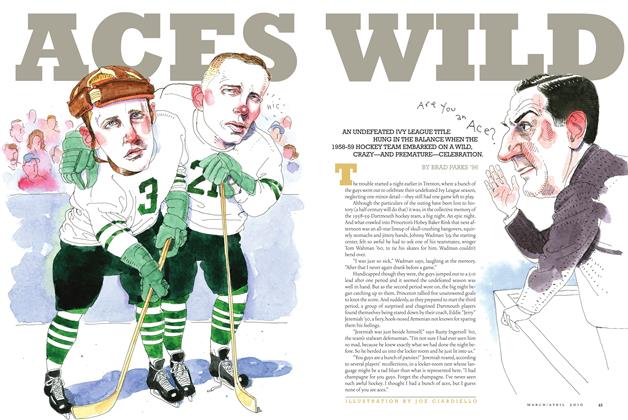

FeatureAces Wild

Mar/Apr 2010 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureA League of His Own

Jan/Feb 2011 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt’s a Whole New Ballgame

Nov/Dec 2011 By BRAD PARKS ’96