THE ULTIMATE OFF-TERM FOR STUDENTS IN 1863? FOR THE DARTMOUTH CAVALIERS IT MEANT SADDLING UP AND HEADING OFF TO THE WAR BETWEEN THE STATES, FULL OF VISIONS OF THEIR OWN HEROISM AND PATRIOTISM.

THEY HAD NO CLUE WHAT THEY WERE IN FOR.

When Abraham Lincoln clled for Union troops to defend Washington, D.C., after the spring 1862 defeat by Stonewall Jackson at Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, Sanford S. Burr, class of 1863, took to his horse. That summer he canvassed campus and crossed the bridge into Norwich, Vermont, to rally support. His proactivity spurred the creation of the College Cavaliers, a company of college men—the majority of whom were Dartmouth students—who embarked on the ultimate summer off-term: a three-month stint in the Civil War. Despite College President Nathan Lords concern that a three-month leave would constitute a "serious detriment" to the students' studies, the College Cavaliers left Hanover on June 18,1862, just before they would have taken final exams. Though the Cavaliers did not achieve any particularly remarkable feats in battle, they certainly were challenged by the inherently tough conditions of wartime life.

Burr, a "wideawake, courteous [gentleman] persuasive in his talk, and commanding in his way of urging support," according to classmate S.B. Pettengill, had applied to the governors of New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont and Massachusetts in search of a volunteer army the boys could join. Each state turned him down, but he eventually found backing from the governor of Rhode Island, who offered to accept the company of students to serve three months in the squadron of cavalry Rhode Island was raising. In addition to 35 students from Dartmouth, Burr had rallied 23 from Norwich University, four from Bowdoin College, a few boys from Union, Williams and Amherst, and another 17 young men from Woodstock, Vermont. Their casual mid-June departure from campus as recounted by Pettengill, a company member, seemed to demonstrate a lack of understanding of what they were about to face.

"They had stepped gaily forth from the College Campus without having visited their homes to say, 'Good-bye.' There had been no parting scenes, nothing in their course thus far to distinguish it much from the usual vacation experience," wrote Pettengill.

But this was the Civil War, and the nonchalance of the company was quickly challenged. Upon arriving in Providence and joining up with a local company to form the 7th Squadron of the Rhode Island Cavalry, the sheltered college boys were confronted with the task of working with "just such men as would naturally be enlisted in a city, where, like a net cast into the sea, the recruiting officer gathers of every set." The Dartmouth men and the unfiltered set did not take to one another. In camp and on the battlefield they "maintained an unwonted degree of exclusiveness in their relations with each other," Pettengill wrote, due in part to the students' belief that they were "apt to be equal, if not superior, in endurance under such service to the more hornyhanded sons of toil."

Despite their differences with the rough men who composed Troop A of the squadron, the Dartmouth students of Troop B worked hard at Dexter Training Ground, drilling for up to six hours per day. Unlike at Dartmouth or at home, there were no days off

"Sunday in camp is not Sunday at home," company member Isaac Walker, class of 1863, wrote in his journal. "Commands of the officers must be obeyed and the commands of such officers as are in our army are generally given without regard to the day or the hour." Yet there was still time for socializing, and the college boys found more acceptable companions with whom to spend their free time: Brown students, who invited the Cavaliers to their fraternity halls for "social and literary entertainments."

At the end of June the company moved to Camp Sprague just outside of Washington. Despite the hardships of Providence, Sprague made Camp Dexter seem luxurious in comparison. To the chagrin of the students, the company continued to train. "They were anxious to give proof of their patriotism at the sabres point and earn a little glory," wrote Pettengill. Disillusionment set in. Not all of the men, it seemed, had understood that war service involved a lot of training and hanging around camp. They were especially peeved by the fact that, as cavalrymen, they were expected to care for their horses.

"They did not understand that they were to be stable boys when they enlisted, and to feed, water, and groom horses did not accord with their ideas of the pomp and circumstance of glorious war,' " wrote Pettengill.

Furthermore, they found the city to be "dirty and disagreeable." Farm animals roamed the streets and their camp, and the oppressive July heat eliminated any desire to sightsee. Pettengill wrote that although the students never entered congressional halls, they still considered the larger questions of the war, debating slavery and freedom from within the confines of their camp.

The Cavaliers' first exciting moment came after they had moved to Winchester, Virginia, at the end of July. Famous Confederate spy Belle Boyd, known as "La Belle Rebelle," spent a night at the Cavaliers' camp as troops escorted her to Washington following her arrest. That evening the boys heard commotion at the picket lines. They later learned that it was a ruse to distract them as Confederates attempted to raid the camp and rescue Belle. The ploy didn't work.

The rest of the students' time at Winchester moved in a slow, redundant rhythm. They alternated between picketing, patrolling the roads, foraging for supplies, participating in reconnaissance missions and riding on Confederate raids. They even elicited the pity of some Southern mothers, who, upon learning the young men were college students, made sure they ate well. Their mounts were less fortunate: Many died from inadequate feeding.

It turned out that the Cavaliers might have been right to scoff at their stable duties, because their Dartmouth education paid off when they finally saw combat. While stationed at Maryland Heights, the group was sent to escort two New York infantry regiments arriving from nearby Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, through the woods to the summit of the heights. The 120th New York Regiment, Pettengill noted, "behaved very badly" when it came under Confederate fire. The Cavaliers' first reaction was to stand before the enemy, where, instead of firing their guns, they "brought into exercise every art of public speaking they had acquired at school in unavailing efforts to arrest the stampede." Some of them pushed forward into the Confederates, "attempting to do by example what they had failed to do by words." Despite the Cavaliers' eventual physical engagement of the enemy, the Confederates took possession of the heights and forced the Cavaliers to flee to Pennsylvania.

"The Rebels are shelling us from the Heights about us and we are giving them as much as they gave us," Walker wrote in his journal on September 14,1862. "We are in hope that reinforcements are on their way to us. May God grant us such a gift."

The Cavaliers did manage one successful military maneuver during their tenure. On their journey to Greenville, Pennsylvania, the 7th Rhode Island captured a Confederate wagon train. Once at Greenville, the students agreed to remain enlisted until the enemy was driven out of Maryland, despite the fact that their term of service had already expired. This allowed them to see action at Antietam, the bloodiest one-day battle of the war. They formed the right flank of Maj. Gen. George McClellan's army, helping to force Gen. Robert E. Lees retreat across the Potomac back to Virginia and providing President Lincoln with the confidence to announce the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

On September 26,1862, the students arrived back in Providence. Fall term at Dartmouth had already begun, and the students were eager to resume their studies. Upon their arrival back in Hanover, the students learned they were expected to take the exams they had missed the previous spring when they left school to enlist. Outraged, Burr immediately went back to Brown and obtained a promise from university President Barnas Sears that if Dartmouth expelled the students for refusing to take exams, Brown would accept them. Not wanting Brown to snatch its heroes, Dartmouth waived the tests and allowed the students to begin fall term.

Despite the tedious hours spent picketing and grooming horses and the "lowbrow" Providence men with whom the college boys were assigned to fight, the Dartmouth College Cavaliers saw action on the battlefield, lost only one man—and wiggled out of some final exams. "It was an intelligent, sincere and a worthy service in which these students engaged," wrote Pettengill, "though like every human work it was transitory and small in itself."

IT WAS DIFFICULT TO tell whIch were the MORE FRIGHTENED, THE BOYS OR THE HORSES.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Outsider

May | June 2013 By BRUCE ANDERSON -

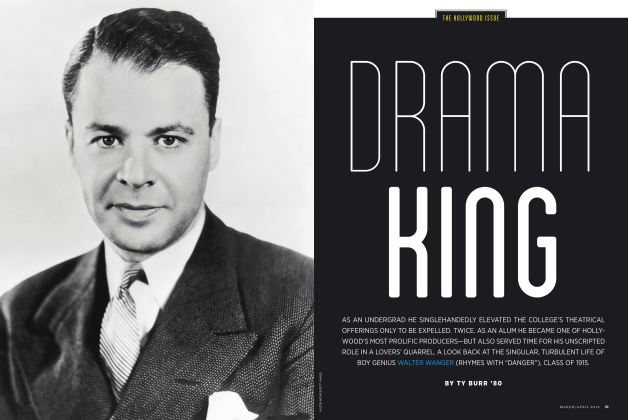

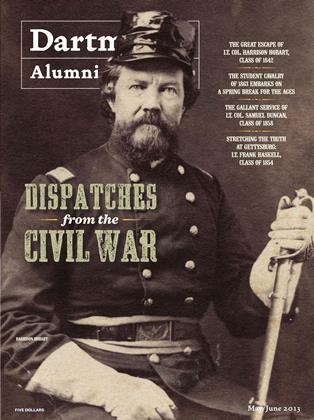

Cover Story

Cover StoryHASKELL THE RASCAL

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

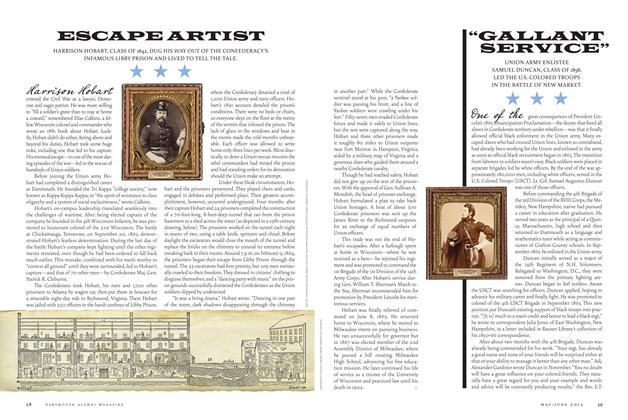

Cover StoryESCAPE ARTIST

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"GALLANT SERVICE"

May | June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May | June 2013 By Sean Plottner -

Cover Story

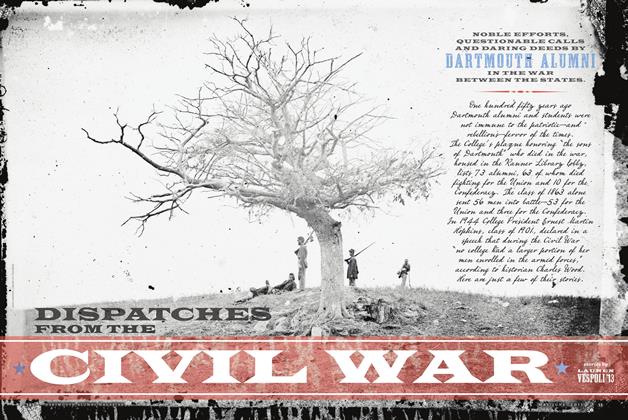

Cover StoryDispatches from the Civil War

May | June 2013 By LAUREN VESPOLI ’13