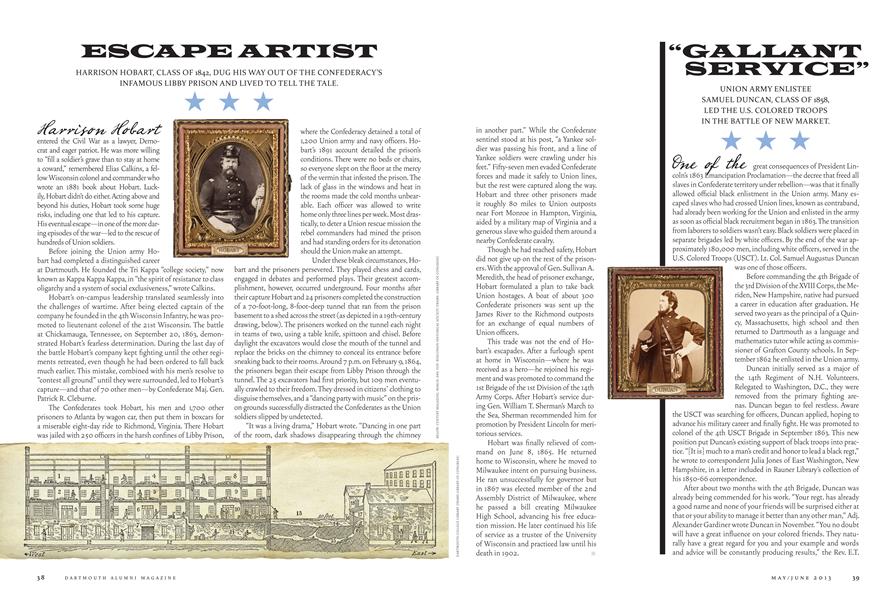

UNION ARMY ENLISTEE SAMUEL DUNCAN, CLASS OF 1858, LED THE U.S. COLORED TROOPS IN THE BATTLE OF NEW MARKET.

One of the great consequences of President Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation—the decree that freed all slaves in Confederate territory under rebellion—was that it finally allowed official black enlistment in the Union army. Many escaped slaves who had crossed Union lines, known as contraband, had already been working for the Union and enlisted in the army as soon as official black recruitment began in 1863. The transition from laborers to soldiers wasn't easy. Black soldiers were placed in separate brigades led by white officers. By the end of the war approximately 180,000 men, including white officers, served in the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Lt. Col. Samuel Augustus Duncan was one of those officers.

Before commanding the 4th Brigade of the 3rd Division of the XVIII Corps, the Meriden, New Hampshire, native had pursued a career in education after graduation. He served two years as the principal of a Quincy, Massachusetts, high school and then returned to Dartmouth as a language and mathematics tutor while acting as commissioner of Grafton County schools. In September 1862 he enlisted in the Union army. Duncan initially served as a major of the 14th Regiment of N.H. Volunteers. Relegated to Washington, D.C., they were removed from the primary fighting arenas. Duncan began to feel restless. Aware the USCT was searching for officers, Duncan applied, hoping to advance his military career and finally fight. He was promoted to colonel of the 4th USCT Brigade in September 1863. This new position put Duncan's existing support of black troops into practice. "[It is] much to a mans credit and honor to lead a black regt," he wrote to correspondent Julia Jones of East Washington, New Hampshire, in a letter included in Rauner Library's collection of his 1850-66 correspondence.

After about two months with the 4th Brigade, Duncan was already being commended for his work. "Your regt. has already a good name and none of your friends will be surprised either at that or your ability to manage it better than any other man," Adj. Alexander Gardiner wrote Duncan in November. "You no doubt will have a great influence on your colored friends. They naturally have a great regard for you and your example and words and advice will be constantly producing results," the Rev. E.T. Rowe predicted in a letter to Duncan in December 1863.

On September 29,1864, Duncan was finally thrust into combat when Gen. Benjamin Butler assigned Duncans regiment to attack a Confederate fort at New Market Heights, Virginia. Butler had specifically chosen Duncans brigade and the 6th Brigade—both under Gen. Charles Paine's command—for the New Market attack in order to demonstrate the capability and willingness of black troops to their many skeptics. At dawn Duncan attempted to surprise Confederate Gen. John Gregg and his 2,000 men, but swampy conditions and armed and waiting Confederates inflicted 452 casualties on Duncans troops and wounded him four times. Duncans men and the 6th Brigade did manage to capture New Market, but at a horrific cost.

Duncan recovered at Chesapeake General Hospital in Virginia. With a little creativity he was able to add some degree of comfort to his stay. He enjoyed delicacies such as "oysters, chickens, and pure sweet milk," he wrote, that were brought into the hospital. Another recovering colonel "brought a cook along with him as a nurse, and she prepares our extras in fine style," Duncan wrote to his mother eight days after New Market. "In this way we manage to get along nicely, in fact I verily believe that I am gaining flesh."

He also proudly mentioned the achievements of his troops: "You will see that [the New York papers] all praise the Colored Troops of Genl. Paines command for what they did on the 29th."

Duncan received honors for "gallant and meritorious service," and the War Department awarded medals of honor to 14 black soldiers who served at New Market. Duncan recovered by February 1865. Writing from North East River Station, North Carolina, he sensed the impending end to four years of bloodshed. Duncan recounted a memorable passage through Wilmington, North Carolina, where the black population enthusiastically welcomed the Union soldiers.

"The slaves comprehend the great question at issue, and invariably assert that they would not fight for their masters, but are ready to fight on our side," Duncan wrote. "I cannot see how the rebellion can long survive."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Outsider

May | June 2013 By BRUCE ANDERSON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHASKELL THE RASCAL

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

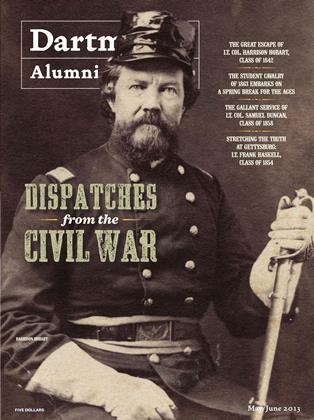

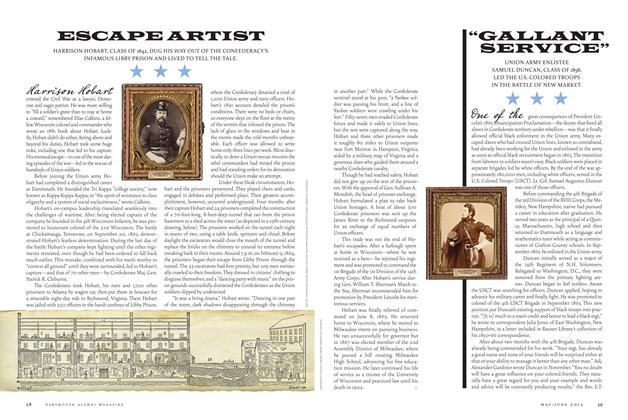

Cover StoryESCAPE ARTIST

May | June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May | June 2013 By Sean Plottner -

Cover Story

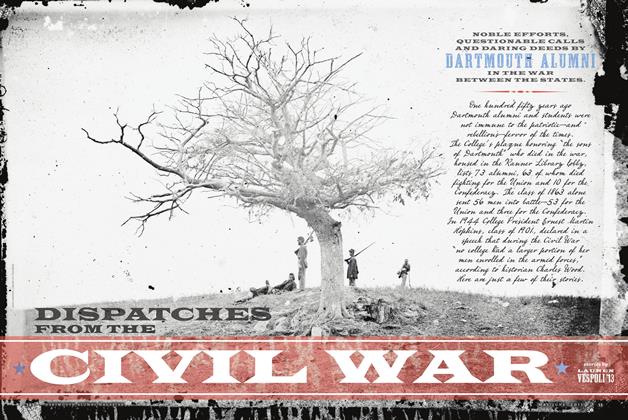

Cover StoryDispatches from the Civil War

May | June 2013 By LAUREN VESPOLI ’13

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Doctor of Philosophy

December 1991 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1960 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10 -

Feature

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

DECEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HOOK VIEWERS WITH AN ADDICTIVE SOAP OPERA STORYLINE

Jan/Feb 2009 By JEAN PASSANANTE '75