SOME SAY IT WAS A "MAGNIFICENT PASSION" THAT LED TO AN ALUM'S EXAGGERATED ACCOUNT OF HIS ROLE AT GETTYSBURG.

OTHERS SAY SIMPLY THAT HE WAS ABSURD AND RECKLESS.

that Lt. Frank Aretas Haskell, class of 1854, fought at Gettysburg, in July 1863 with the 6th Wisconsin Infantry. Yet 46 years later his role in the battle—which had the largest number of casualties in the war—was the subject of a heated debate. Did Haskell ride solo along the enemy line of Gen. George Pickett's charge of 12,000 Virginians while members of the 11th Corps of the Philadelphia brigade fled, as he claimed? Or was Haskell lying?

Originally from Tunbridge, Vermont, Haskell graduated with honors. He then moved to Madison, Wisconsin, where he joined the law firm of Orton, Atwood and Orton. He had a successful career practicing law until 1861, when the Civil War broke out. That June he was commissioned as first lieutenant of the first company of the 6th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry. Leading up to Gettysburg, Haskell's military service included battles at Gainesville, Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg and Charlottesville. He was known for his "intelligence and courage, for his generosity of character and exquisite culture," said Brig. Gen. Francis A. Walker of the Union Army of the Potomac, "long before the third day of Gettysburg."

As many as 51,000 soldiers were ultimately killed, wounded or captured in the three days of fighting at Gettysburg as Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was driven out of the north. Two weeks after this bloodbath Haskell sent a long, detailed account of his role in the battle to his brother in Portage, Wisconsin. He didn't intend the account to be made public, but his brother, impressed by the stoiy, gave it to the editor of the weekly Portage State Register, who published it in a 72-page pamphlet.

Because of Haskell's thorough descriptions of the battle, the pamphlet became popular among military experts and received literary praise. It was reprinted in 1898 with some omissions as part of the "Dartmouth College History of the Class of 1854" to no notable reaction. But when the Military Order of the Loyal Legion Commandery of Massachusetts and the Wisconsin History Commission republished the pamphlet in its entirety in 1908, the account was met with ire and contempt.

The Philadelphia Brigade Association—a veterans' group for the Philadelphia Brigade—was so offended by Haskell's unflattering portrayal that it published a pamphlet refuting his "malicious statements" in 1909—46 years after the battle.

The association acknowledged Haskell's service as aide-de-camp on Maj. Gen. John Gibbon's staff during Gettysburg and his continued service as colonel of the 36th Wisconsin Regiment in 1864. But "as a writer of events of the war he was absurd, reckless and unreliable," the association charged. His "false and malevolent" stories were "unworthy of a class at Dartmouth College."

Haskell's account directly challenged the Philadelphia Brigades honor. He reported that members of the 11th Corps "sought to hide like rabbits" while he "ordered those men to 'halt' and 'face about' and 'fire,' and they heard my voice and gathered my meaning and obeyed my commands." While the Philadelphians were allegedly fleeing Pickett's men, Haskell wrote he was the "first mounting that stormy crest before the enemy, not forty yards away" and his was "the only horse there during the heat of that battle." The Philadelphians rebutted this claim with sarcastic awe that Pickett's men "who made such slaughter in OUR RANKS AT LONG RANGE could not kill first Lieutenant Frank Aretas Haskell."

Did he ride solo along the enemy line of Pickett's charge of 12,000 Virginians, as he claimed, or was he lying?

The problem with Haskell's story, the brigade argued, was that it was "hastily written...between his hours of duty... while not yet fully recovered from the delirium of excitement that overcame him in the exalted position he claims to have assumed." Haskell wrote that he was overcome by "magnificent passion" during the battle; the Philadelphians used this sentiment to discredit the account even though he wrote it two weeks after the battle, presumably having had time to cool off. They published the account of Col. Charles H. Banes of the Philadelphia Brigade as truth in a section of the pamphlet called "Banes versus Haskell." The veterans praised the "calm, temperate, lucid, truthful and dignified statement" of Banes' tales of the brigade's bravery over Haskell's words of disoriented passion.

The association accused any who published Haskell of being "vaccinated by the Haskell virus of vanity and venom," and transmitting "the buffoonery of Haskell." They requested the organizations publishing Haskell's account to make a public disclaimer for its accuracy, otherwise the State of Wisconsin and the Loyal Legion of Massachusetts, "to say it very mildly, would be the reverse of creditable."

The total killed, wounded and missing of the Philadelphia Brigade at Gettysburg was more than 32 percent, or about one soldier killed to every three engaged in battle. "Call you this 'running like rabbits'?" the Philadelphians asked in their pamphlet.

Even a dear friend of Haskell's asserted the dishonesty of his Gettysburg tale. Yates Selleck, a military agent for the State of Wisconsin, wrote into the public ledger of Philadelphia almost 50 years after Haskell's death to correct his mistruths. "I was intimately acquainted with Haskell and had several conversations with him after the Battle of Gettysburg entirely in regard to that battle and I have good reason for stating that had Haskell survived until the close of that blood-stained chapter in our nation's history, the tainted assertions contained in his personal diaries would, happily, never-never have been made public, wrote Selleck. (Haskell was killed in action at Cold Harbor, Virginia, on June 3, 1864.)

Meanwhile, many generals had supported Haskell's claims in their own reports on the battle. "When the contending forces were but fifty or sixty yards apart, believing that an example was necessary, and ready to sacrifice his life, [Haskell] rode between the contending lines with a view of giving encouragement to ours," wrote Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock in his official report. General Gibbon wrote that Haskell "did more than any other one man to repulse Pickett's assault at Gettysburg."

Whether the Philadelphia Brigade Association was telling the truth or attempting to save face remains unknown. The real story rests with Haskell in his grave.

Additional reporting by Seymour Wheelock '40.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Outsider

May | June 2013 By BRUCE ANDERSON -

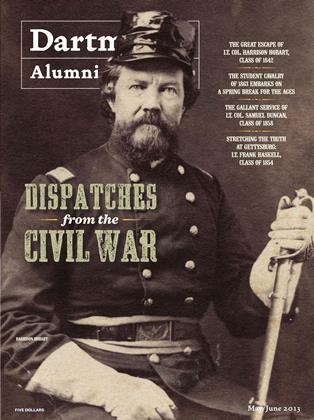

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

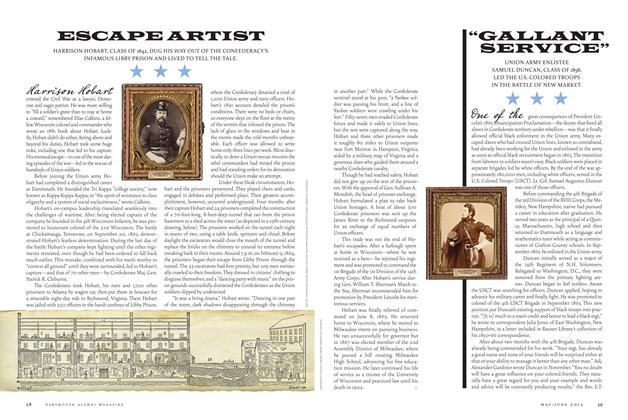

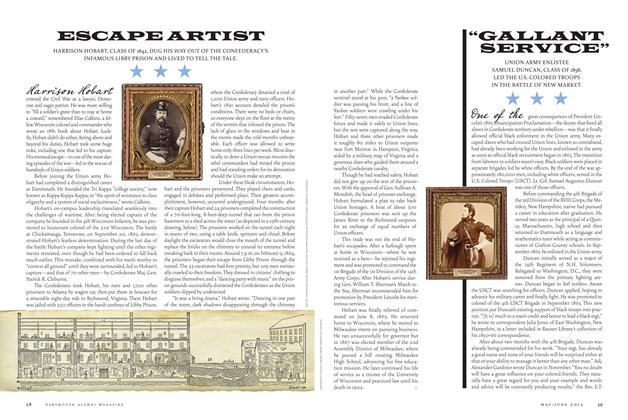

Cover StoryESCAPE ARTIST

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"GALLANT SERVICE"

May | June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May | June 2013 By Sean Plottner -

Cover Story

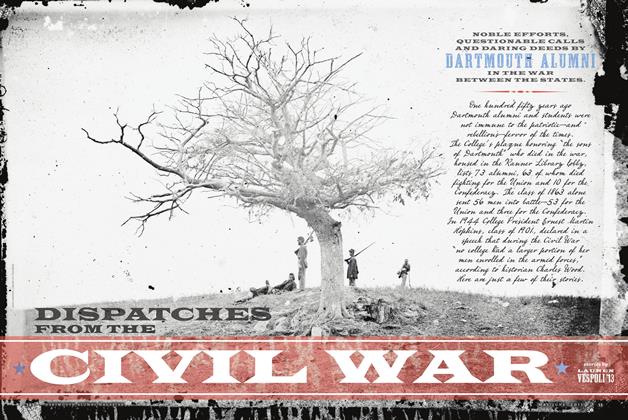

Cover StoryDispatches from the Civil War

May | June 2013 By LAUREN VESPOLI ’13