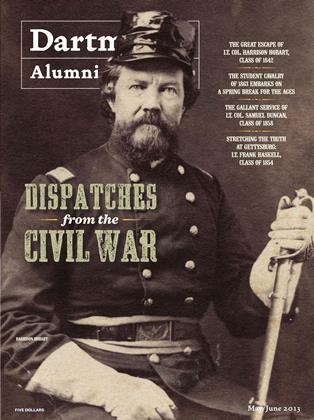

HARRISON HOBART, CLASS OF 1842, DUG HIS WAY OUT OF THE CONFEDERACY'S INFAMOUS LIBBY PRISON AND LIVED TO TELL THE TALE.

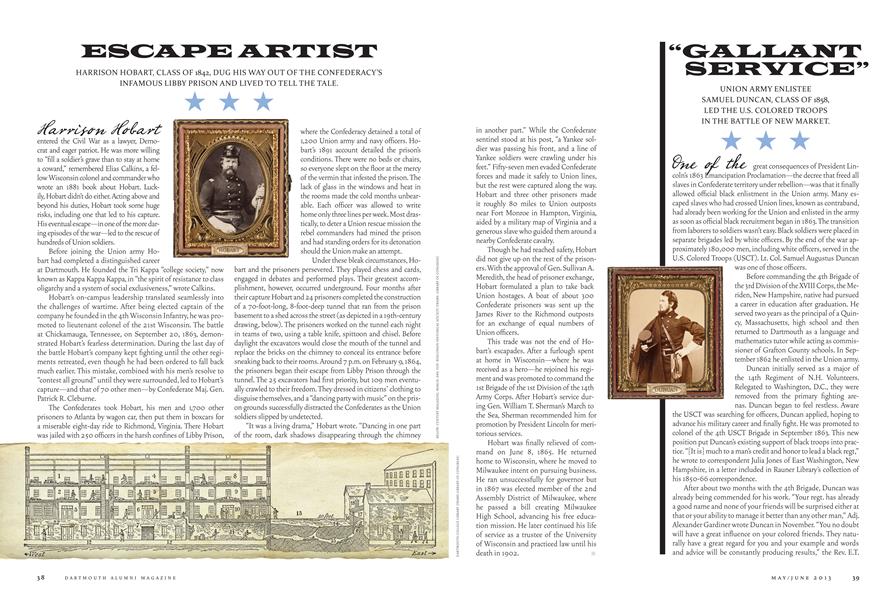

entered the Civil War as a lawyer, Democrat and eager patriot. He was more willing to "fill a soldiers grave than to stay at home a coward," remembered Elias Calkins, a fellow Wisconsin colonel and commanderwho wrote an 1881 book about Hobart. Luckily, Hobart didn't do either. Acting above and beyond his duties, Hobart took some huge risks, including one that led to his capture. His eventual escape—in one of the more daring episodes of the war—led to the rescue of hundreds of Union soldiers.

Before joining the Union army Hobart had completed a distinguished career at Dartmouth. He founded the Tri Kappa "college society," now known as Kappa Kappa Kappa, in "the spirit of resistance to class oligarchy and a system of social exclusiveness," wrote Calkins.

Hobart's on-campus leadership translated seamlessly into the challenges of wartime. After being elected captain of the company he founded in the 4th Wisconsin Infantry, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 21st Wisconsin. The battle at Chickamauga, Tennessee, on September 20, 1863, demonstrated Hobart's fearless determination. During the last day of the battle Hobart's company kept fighting until the other regiments retreated, even though he had been ordered to fall back much earlier. This mistake, combined with his men's resolve to "contest all ground" until they were surrounded, led to Hobart's capture—and that of 70 other men—by Confederate Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne.

The Confederates took Hobart, his men and 1,700 other prisoners to Atlanta by wagon car, then put them in boxcars for a miserable eight-day ride to Richmond, Virginia. There Hobart was jailed with 250 officers in the harsh confines of Libby Prison, where the Confederacy detained a total of 1,200 Union army and navy officers. Hobart's 1891 account detailed the prisons conditions. There were no beds or chairs, so everyone slept on the floor at the mercy of the vermin that infested the prison. The lack of glass in the windows and heat in the rooms made the cold months unbearable. Each officer was allowed to write home only three lines per week. Most drastically, to deter a Union rescue mission the rebel commanders had mined the prison and had standing orders for its detonation should the Union make an attempt.

Under these bleak circumstances, Hobart and the prisoners persevered. They played chess and cards, engaged in debates and performed plays. Their greatest accomplishment, however, occurred underground. Four months after their capture Hobart and 24 prisoners completed the construction of a 70-foot-long, 8-foot-deep tunnel that ran from the prison basement to a shed across the street (as depicted in a 19th-century drawing, below). The prisoners worked on the tunnel each night in teams of two, using a table knife, spittoon and chisel. Before daylight the excavators would close the mouth of the tunnel and replace the bricks on the chimney to conceal its entrance before sneaking back to their rooms. Around 7 p.m. on Februaiy 9,1864, the prisoners began their escape from Libby Prison through the tunnel. The 25 excavators had first priority, but 109 men eventually crawled to their freedom. They dressed in citizens' clothing to disguise themselves, and a "dancing party with music" on the prison grounds successfully distracted the Confederates as the Union soldiers slipped by undetected.

"It was a living drama," Hobart wrote. "Dancing in one part of the room, dark shadows disappearing through the chimney in another part." While the Confederate sentinel stood at his post, "a Yankee soldier was passing his front, and a line of Yankee soldiers were crawling under his feet." Fifty-seven men evaded Confederate forces and made it safely to Union lines, but the rest were captured along the way. Hobart and three other prisoners made it roughly 80 miles to Union outposts near Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, aided by a military map of Virginia and a generous slave who guided them around a nearby Confederate cavalry.

Though he had reached safety, Hobart did not give up on the rest of the prisoners. With the approval of Gen. Sullivan A. Meredith, the head of prisoner exchange, Hobart formulated a plan to take back Union hostages. A boat of about 300 Confederate prisoners was sent up the James River to the Richmond outposts for an exchange of equal numbers of Union officers.

This trade was not the end of Hobart's escapades. After a furlough spent at home in Wisconsin—where he was received as a hero—he rejoined his regiment and was promoted to command the ist Brigade of the 1st Division of the 14th Army Corps. After Hobart's service during Gen. William T. Shermans March to the Sea, Sherman recommended him for promotion by President Lincoln for meritorious services.

Hobart was finally relieved of command on June 8, 1865. He returned home to Wisconsin, where he moved to Milwaukee intent on pursuing business. He ran unsuccessfully for governor but in 1867 was elected member of the 2nd Assembly District of Milwaukee, where he passed a bill creating Milwaukee High School, advancing his free education mission. He later continued his life of service as a trustee of the University of Wisconsin and practiced law until his death in 1902.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Outsider

May | June 2013 By BRUCE ANDERSON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHASKELL THE RASCAL

May | June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"GALLANT SERVICE"

May | June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May | June 2013 By Sean Plottner -

Cover Story

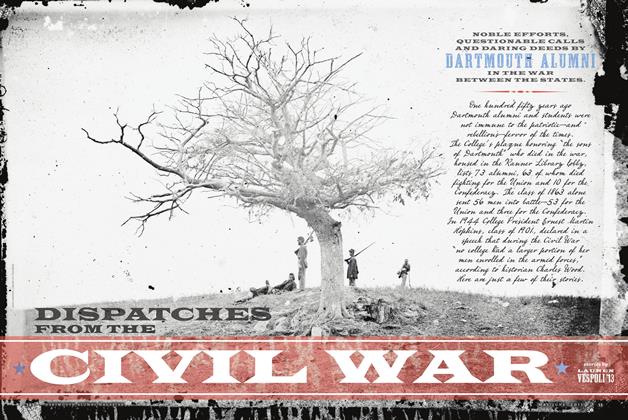

Cover StoryDispatches from the Civil War

May | June 2013 By LAUREN VESPOLI ’13

Features

-

Feature

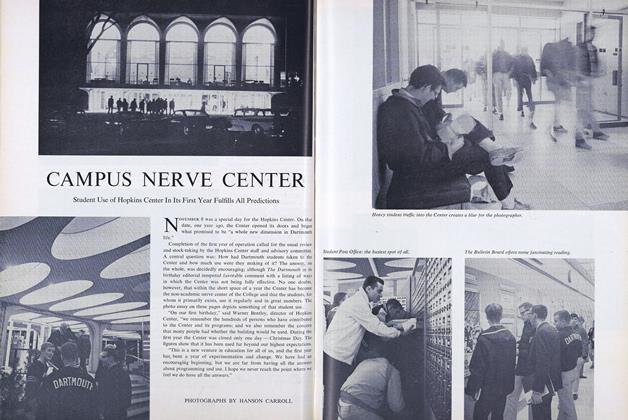

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

DECEMBER 1963 -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

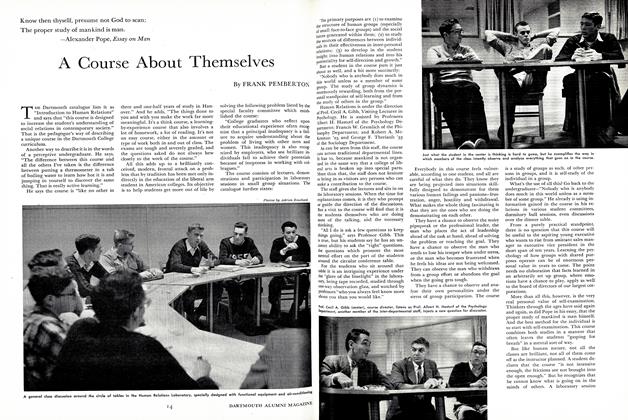

FeatureA Course About Themselves

January 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureSummer Term Close to Count-Down

APRIL 1963 By R.J.B. -

Feature

FeatureThe Next Bus Home

September 1993 By Regina Barreca '79