John Gilbert Winant's principled actions are virtually unknown in contemporary politics.

Convocation prompts us to consider the purposes of a liberal education and to ask how we might fashion our lives to exemplify those purposes. One approach is to reflect upon the lives of those whose careers may inspire us and guide us.One such person was John Gilbert Winant—bornin 1889, died in 1947, a child of the first half of the century now ending. Like so many of the others of whom I have spoken, Winant was an idealist. His life of public service embodied the highest purposes of a liberal education, and it was rooted here, in New Hampshire.

In the end, Winant's storyis a poignant and tragic one. I want to share his story with you for two reasons: because it exemplifies an inspiring idealism and because it teaches an important lesson in humility, reminding us of the limits on our capacity to understand the interior lives of others.

One could not grow up in this state, as I did, without realizing that John Winant wasan extraordinary human being, a man set apart by character and by a singular devotion to the common weal—a man who was one of New Hampshire's contributions to national greatness, much as Jefferson was one of Virginia's.

The name of John Gilbert Winant is now almost forgotten. Yet he was widely admired during his lifetime, regularly receiving respectful, even adulatory, attention in the national press, especially for his exemplary service as governor of New Hampshire. Comparisons of his character to that of Lincoln were frequent and sincere. The historian Allan Nevins described him as "one of the best idealists and most truly humane men" of the age. In 1936 he was prominently mentioned as a candidate for president of the United States.

During World War 11, he served with distinction as Ambassador to the Court of St. James. In 1946 he returned to his home in Concord, a glowing toast from his wartime friend and admirer Winston Churchill still ringing in his memory. He had earned the respectof the world for his quiet, selfless contributions to winning the war. At age 58, he seemed to have many years of public service still before him. But that was not to be.

a John Gilbert Winant was raised on Pleasant Street in Concord, three miles from the State House, and educated at nearby St. Paul's School. He attended Princeton but he did not graduate. Instead, he returned to teach history at St. Paul's, where the rector recognized in him "a great and rare gift of influencing boys along the very highest paths." His political career began with his election to the state legislature in 1916. After serving in the American Air Service during World War I, he became assistant rector at St. Paul's. But public life again beckoned, and Winant went on to serve three terms as governor of New Hampshire—from 1925 to 1927 (when he was the youngest governor in the nation) and from 1931 to 1935.

Winant was a lifelong Republican whose humanitarian principles transcended party lines. Influenced by the writings of Charles Dickens and John Ruskin and inspired by the examples of Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt, as governor he was a forceful advocate of progressive reform initiatives, including a 48-hour work week for women and children, a minimum wage, and the abolition of capital punishment.

In 1935 franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him as the first chairman of the Social Security Board. However, when Social Security became a major issue during the 1936 presidential campaign, Winant resigned that position so that he could better defend the new program, alongside President Roosevelt, from criticisms by the Republican candidate and his party. Winant's decision to resign in order to support a program in which he believed unreservedly even though it meant repudiating his own political party offers a model of principled action that is, alas, virtually unknown to contemporary politics.

In February 1941, President Roosevelt appointed Winant ambassador to Great Britain. Committed body and soul to fighting totalitarianism, Winant was responsible for implementing Roosevelt's energetic policy of aiding Britain's war efforts.

He drove himself relentlessly, day and night, without a break; his devotion was allconsuming. He never lost sight of the fact that the pain of the great international depression and the suffering brought on by war had a human face—indeed, individual human faces.

During the Battle of Britain, he walked the streets of London, ablaze from the aerial bombardments, offering assistance to the injured amidst the rubble of their homes and stores, sharing their hardships and dangers. His shy sincerity and quiet fearlessness endeared him to the British and helped buoy the nation. As Prime Minister Clement Attlee said many years later, he "brought a feeling of warmth, confidence and courage to the British people in their time of greatest need."

Winant was rare among public figures in being a very private person. And the temper of the private man created and influenced the actions of the public man. Usually we have distrusted such men in our politics (they have too much of Cassius, if not Hamlet, about them) and have made them figures of our literature instead. Winant's career illustrates that a person with a thoughtful private life can also be an effective public figure.

To read Winant's speeches is to sense the same greatness of soul, the same magnanimity of purpose, the same simplicity of language that appears in Lincoln's speeches. Consider, for example, the words of farewell that Winant spoke to the New Hampshire legislature when he was named ambassador to the Court of St. James:

"We are today the 'arsenal of democracy,' the service of supply against aggressor nations. Great Britain has asked that we give them the tools that they may 'finish the job.' We can stand with them as free men in the comradeship of hard work, not asking but giving, with unity of purpose in defense of liberty under law, of government answerable to the people.

"In a just cause, and with God's goodwill, we can do no less."

Winant's commitment to social justice was well known on both sides of the Atlantic. He was confident, as he told striking coal miners in Durham, England, in June of 1942, that "our supply of courage will never fail. We have the courage to defeat poverty as we are defeating Fascism; and we must translate it into action with the same urgency and unity of purpose that we have won from our comradeship in this war."

With a simple eloquence, Winant told the striking miners, "This is the people's democracy. We must keep it wide and vigorous, alive to need, of whatever kind, and ready to meet it, whether it be danger from without or well-being from within, always remembering that it is the things of the spirit that in the end prevail—that caring counts, that where there is no vision people perish, that hope and faith count and that without charity there can be nothing good, that daring to live dangerously we are learning to live generously, and believing in the inherent goodness of man we may meet the call of your great Prime Minister and 'stride forward into the unknown with growing confidence.'"

His speech was a resounding success: he had not mentioned the work stoppage, but, rather, had praised the miners' role in the long and hard war effort. The Manchester Guardian called it "one of the great speeches of the war." Winant's words, it said, had invested the phrase "a people's war" with new meaning. By joining the life-or-death struggle to preserve democracy with the concrete social purpose of improving the economic circumstances of working people, Winant had deepened the war's meaning for the common man. The miners went back to their crucial work.

Throughout the war, Winant traveled with Churchill to many parts of England, and he was a frequent weekend guest at the prime minister's country home, where their work together continued. While his diplomatic efforts were often eclipsed by the unusually close relationship between Roosevelt and Churchill, Winant nevertheless deserves much credit for managing the eracial relations between this country and Great Britain during those perilous times.

President Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. For Winant, the death of his close friend and mentor was devastating. He keenly felt the loss of a man he admired so greatly, and the loss came when Winant himselfwas utterly exhausted. He must have felt isolated and abandoned that his career had been cut short. By supporting Roosevelt in the 1936 election, Winant had alienated himself from his fellow Republicans. With Roosevelt gone, he now reported to Harry S. Truman, a President who neither knew him well nor appreciated the extent of his war-time efforts.

Then, but three months later, a landslide victory by the Labor Party swept Prime Minister Churchill out of office. Everywhere Winant turned, he saw the drama in which he had participated so significantly drawing to a close.

From the outset of the war in Europe, Winant had dreamed of the peace that would follow victory. He had told President Roosevelt that he hoped to be made Secretary General of the newly formed United Nations. In the end, however, international politics would preclude the appointment of an American. Increasingly, too, the new president turned to others to form and effectuate policy pertaining to relations with Great Britain. Finally, in March of 1946, President Truman appointed W. Averell Harriman to be Winant's successor as our ambassador to London. It was time for Winant to return home to New Hampshire.

In a farewell tribute, Churchill said that Winant had "been with us always, ready to smooth away difficulties and put the American point of view with force and clarity and argue the case with the utmost vigour, and always giving us that feeling, impossible to resist, how gladly he would give his life to see the good cause triumph. He is a friend of Britain, but he is more than a friend of Britain—he is a friend of justice, freedom, and truth."

When, more than a year after President Roosevelt's death, Congress met in joint session to pay homage to the President who had led the nation in meeting the two most formidable challenges of the century the Great Depression and the Second World War it was Winant who was chosen to give the memorial address. He said: "The things a man has lived by take their place beside his actions in the true perspective of time, and the inner pattern of his life becomes apparent. In the long range, it is the things by which we live that are important, although the timing and circumstance play their part."

At home in New Hampshire, Winant's frustrations grew. After three decades of public life, he confronted the necessity of accommodating himself to the quieter, slower pace of a private citizen. He was in debt, under pressure to complete a series of books on his experiences, and troubled by a darkening personal depression.

On November 3,1947, the very day that his only book, Letter from Grosvenor Square, was published, John Gilbert Winant committed suicide at his home in Concord. His publisher had rushed a copy of the book to him, but he never saw it.

Winant had reportedly been despondent for some time. His diplomatic stature, his public achievements, and his great capacities for service gave no protection against the brooding depths of melancholia and hopelessness that ultimately overwhelmed him.

His friends and admirers inevitably searched for the reasons that a man of such gifts and such distinction would take his own life. Was it, they wondered, because he suffered throughout his life—from his early, frustrated days at Princeton from a persistent and painful self-doubt? Was it because he felt unworthy of the professional success he had achieved? Was it because he thought his career was over, and that he was permanently cut off from power, influence, and prospects? Was it because, with the emergence of the Cold War, he believed, like Hamlet, that the times were out of joint, and despaired of the achievement of a more generous nation at home and a more peaceful international community abroad?

We shall never know whether any of these explanations is correct. We know only that his private life must have been tormented, for many years, by demons that went unaddressed; and that depression, as Dante said of hell, is an endless, hopeless conversation with oneself, and that its outcome is sometimes self-destruction.

A liberal education is one of the means by which we prepare ourselves to understand the nature of being human. It enlarges our understanding of men and women and deepens our insight into the most intimate reaches of the human heart. But a liberal education, for all of its illuminating power, ultimately casts only a partial light on the moral tensions and anguished emotions of others.

Standing mute before the numbing fact of Winant's death, I think inevitably of Edwin Arlington Robinson's poem, "Richard Cory":

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,We people on the pavement looked at him:He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored, and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed, And he was always human when he talked; But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

"Good-morning," and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich yes, richer than a king, And admirably schooled in every grace; In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light, And went without the meat, and cursed the bread;

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, Went home and put a bullet through his head.

John Winant's death reminds us that we can never fully know how other persons experience their lives. We can never assume that those who are more eminent than we must therefore be more happy. When we compare ourselves unfavorably to others, when we envy those who seem more fortunate than we, it is wise to remember that what we see from the outside may not be what those persons experience from the inside.

In assessing the life of John Gilbert Winant, few observations are more apt than the words he spoke in his tribute to President Roosevelt: "But greatness does not lie in the association—even the dominating association—with great events....Greatness lies in the man and not the times; the times reflect it only. Greatness lies in the proportion."

John Winant's death was a grievous public tragedy as well as an excruciating personal loss, for we will never know the further contributions he might have made, the future roles he might have played. That is especially true because his life, like Roosevelt's, had a proportion between action and idealism that truly bespeaks greatness.

JohnWinantwasa quiet man from a small state a school teacher without a college degree who wasimbued with a sense of destiny. By drawing upon an elevated spirit and an unswerving idealism, he contributed greatly to the nation's coral reef of character.

Winant

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

December 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

December 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

Feature

FeatureSHUE HAPPENS

December 1996 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

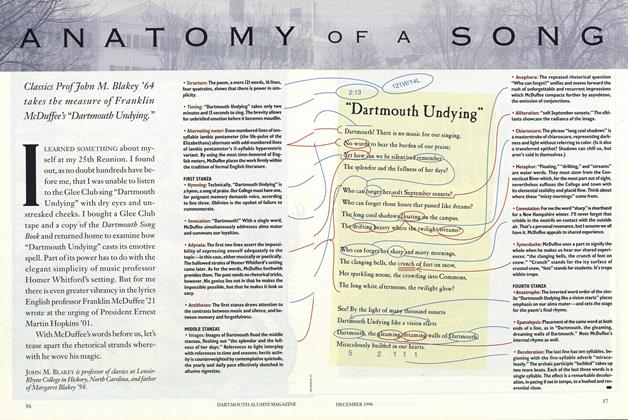

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

December 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Article

ArticleThose Who Got It Out

December 1996 -

Article

ArticleSpeak!

December 1996 By Christopher Kenneally '81

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

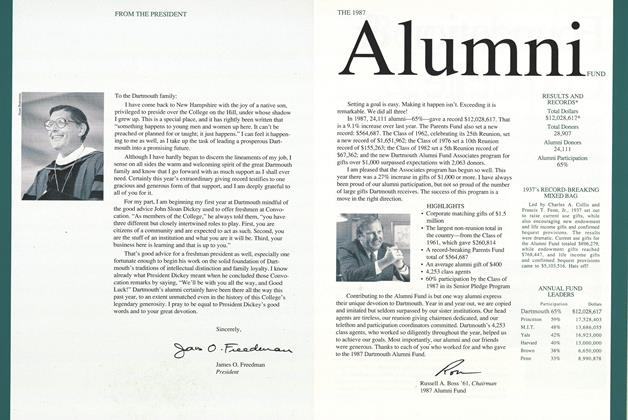

ArticleFROM THE PRESIDENT

OCTOBER • 1987 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWomen and Men of Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleEdward Tuck

APRIL 1932 -

Article

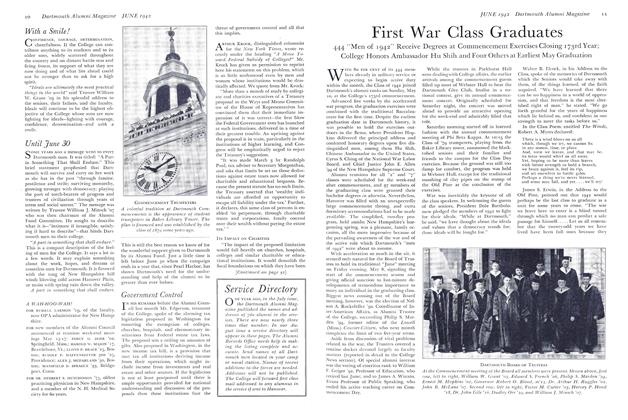

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleCitizen's Book. . .

January 1953 -

Article

ArticleDid the recent cloning of a sleep catch the ethics community off guard?

MAY 1997 -

Article

ArticleFlying Lightning?

November 1952 By REGINALD F. PIERCE JR. -

Article

ArticleSpring Sorcery

APRIL 1932 By William Kimball Flaccus '33