The ninth annual conference of teachers in secondary schools was held at the College, May 13 to 15. The attendance was smaller than in some years, but the quality of the papers presented and the vigor and usefulness of the discussions have hardly been equalled in any past year.

The first session was opened with a fitting address of welcome by Professor Home, who added a brief sketch of some of the applications of pragmatism to education ; while not holding pragmatism to be a sufficient philosophical theory, the speaker believed that many of these applications must commend themselves to teachers.

The address of the evening was given by Professor J. C. Kirtland, Head of the Department of Latin of Phillips Exeter Academy. Mr. Kirtland has recently visited some of the great English schools as delegate of the National Civic Federation. His intimate knowledge of current problems in our own secondary schools, and the very exceptional opportunities that he enjoyed in his access to the inner life of some of the most famous of the English schools, gave peculiar value to his observations. He was most happy in his choice of material, presenting details of the daily work of which one learns little in the books on foreign education, arid at the same time interpreting them as showing the ideals and aims of English education. The following extracts from his address give only a hint of its breadth and insight:

Secondary schools in England, he said, are of three "classes: (1) Private schools; (2) a group of seventeen secondary schools, founded since 1904 by the London County Council, and supported by taxation: (3) about fifty older endowed schools which receive an annual subsidy from the County Council and are to some extent under its control; (4) the old and famous public schools, so-called, endowed institutions like Rugby, Eton, and Charterhouse, not supported by the state, and charging high tuition fees.

Mr. Kirtland gave a detailed description of Charterhouse as a typical school of the fourth and most important group. Pupils enter the. school between eleven and fourteen years of age; they must pass school entrance examinations in the following subjects: Latin at sight, Latin prose, Latin grammar, French translation, composition, and grammar, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, Greek translation, sentences, and grammar. Optional subjects for admission are: Scripture, English history, geography, English grammar and composition, and elementary science.

The school has about forty masters and between 500 and 600 boys. The organization and classification of students depend on their classical work. In the highest "form," the sixth, scholars have twenty recitations in the classics each week, two in French, and four in mathematics. The subjects set for the classical examination of the sixth form in 1908 were: The First Epistle to the Corinthians, Book V-VII of the Odyssey, the OedipusRex, Book II of Thucydides, Cicero's Letters, the Ars Poetica, Books I-III of Lucretius; Oman's Seven Roman Statesmen, Gwynn's Masters of English Literature, an English essay; Greek Literature, grammar and composition; translation at sight from Herodotus, Thucydides, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Sallust, Tacitus, Lucan, and the Georgics of Vergil. The subjects set for the mathematical examination Of the same form in 1908 were trigonometry, algebra, geometry, arithmetic, conics, and statics.

The present tendency in England is to employ Latin as the chief instrument of grammatical and linguistic discipline, and when the foundation has been thus laid to study Greek mainly for its literary content.

Mr. Kirtland laid much emphasis on the far greater proportion of time that the instructor in an English school gives to teaching as, compared with hearing of recitations, and to the ease of promotion in the case of the individual boy whenever he is ready for the work of an upper form. Pie also commented on the facility of the students in translation into idiomatic English, and the large part that sight reading plays in their training and in their final tests. The memorizing of passages of the classical authors is also much more practiced than in our schools.

In reviewing the work of the schools as a whole, he said, "I feel sure that they have the advantage of us in three respects: in the elementary stage they study solid subjects; they give their time"arid thought then and later in the secondary school to a few studies; and these studies are humanistic."

But the attention given to classical study does not exclude sound training in science for those whose parents wish it. Science courses at Eton include physics, chemistry, biology, botany, zoology, physiology, geology, and mineralogy.

The schools offer constant stimulus to scholarship through competitive honors and scholarships, The head boy of a school and the head boys of the several houses, with whom rests the real leadership, as well as much of the authority, in the schools, owes his position in every case to his superiority in his studies, never to athletic prowess or political manipulation.

The most noticeable feature of the school sports is the fact that all boys take active part in them; sports are carried on for sport's sake; competition between schools plays a small part, and most of the exercise is in the open air rather than in the gymnasium.

The public schools emphasize the building of character above everything else. Religious worship is prominent in the life of the schools, and the boys are engaged in many Christian and philanthropic enterprises.

The session of Friday forenoon was given to the discussion of college entrance requirements in general, this being the main topic of the conference. Professor Emery gave the results of a careful study of college catalogues from the earliest years to the present, showing the successive changes in the entrance requirements and in the machinery of their administration. He found a remarkable tendency to uniformity of requirements in the earliest period, at least as printed in the announcements of the colleges, but he suggested that differences in rigor of administration ma) have made real and" important differences in actual requirement. He showed that great diversity in requirements gradually came in until in 1879 a movement was begun by the New England colleges that brought about a considerable degree of uniformity and a clearer definition of requirements; this movement culminated in 1886 in the formation of the Commission of Colleges in New England, which year after year held joint conferences with college and preparatory instructors of the several departments of study ; the recommendations of this commission, based on such joint conferences, are the basis of most of the present entrance requirements of the New England colleges. Similar bodies have done like work for other large sections of the country.

Professor Emery sketched the work done by the famous "Committee of Ten" appointed by the National Educational Association in 1892, whose report has done so much to shape the courses of study in secondary schools throughout the United States, and to establish the principle that the colleges must adapt their requirements to the work of the schools.

The paper closed with a statement of the work of the two central bodies now in control of college admission in most of the New England colleges, the New England College Entrance Certificate Board, and the College Entrance Examination Board.

Dean Emerson laid before the conference certain changes that have been recommended to the Dartmouth faculty by their committee on admission, and which will soon be acted upon. Of these the most important is the substitution of counting admission subjects according to the units adopted by the Carnegie Institution and by the College Entrance Examination Board. Under the new system all studies will be credited with the same number of units when pursued for the same length of time; under the old system some studies, Latin for example, have been given more credit than some others pursued for the same time.*

The discussion that followed was opened by a paper of marked force and insight by Principal Swett of the Franklin, N. H., high school: Mr. Swett set forth the peculiar situation in New Hampshire, by which some seventy high schools in the state stand as approved preparatory schools by authority of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, after careful examination of their work," while only about half of these schools have certification privileges at Dartmouth. Schools in New Hampshire can come into the privilege only by action of the New England Certificate Board, whose requirements are such that many of the smaller high schools are unable to comply with them. Mr. Swett urged that schools which meet the rigid requirements of the state authorities ought not to be required to appeal to a board outside the state, and one on which secondary schools have no representation, when they seek certificate privileges in the college of their own state.

The question presented by Mr. Swett's paper was new to most of the college men present, and it was their judgment that it ought to receive most careful consideration by the college faculty. The present system of inspection and approval of preparatory schools by the New Hampshire state authorities has been largely developed since the Col- lege adopted the system of approval of schools through reference to the New England Board.

Mr. Swett also pointed out the injustice that may be done a school by judging its work by the record that a single student from the school makes in his freshman year in college, and urged the need of more careful investigation of the real cause of failure in college in any individual case, before charging the failure to lack of preparation.

A plea was also made for the recognition by the college of some subjects that ought to be given by the schools, but are not now counted for college admission; elementary economics was cited as such a course.

In the remarks that followed the paper the advantages and disadvantages of a system of inspection of preparatory schools by delegates from the colleges were discussed. It was made clear that such a system is open to grave abuse, and may work serious injustice to the teachers, yet that with proper care it may be made of great service to school and college alike.

As to the question whether present admission requirements in any department are excessive, it was stated that too many subjects are required in algebra, that the advanced requirements in writing Latin and Greek are too great, and that the amount of French to be read according to the Dartmouth requirements is excessive.

There was also a significant discussion of the inequality of the supposedly equal admission "units." It was shown that in college admission as much credit is given for a year of beginners' German taken by children in the first year of the high school, without any previous training in a language other than their own, as to a year of beginners' German taken by seniors in the school, who have had Latin, Greek, and French, and who will in the one year do work that is equivalent to two or three years' work of the other scholars.

As to the question whether the requirements for admission as a whole are excessive, it was said that only a few exceptionally bright scholars in a large school are found to be able to meet the entire requirement thoroughly. In one academy only three graduates out of twenty-five who entered college last year could take complete certificates; their work was deficient either in quantity or quality. This seems to show that the total work required for college admission is so great that either quality or quantity has to be sacrificed by the scholar"of average ability.

One of the most interesting features of the discussion was the stress laid by several speakers, notably Professor Bolser of the College, and Doctor Gallagher of Thayer Academy, upon their conviction that very much of the difficulty in meeting admission requirements lies in the (entire unwillingness of many pupils to do work that calls for steady application of mind, and the desire of their parents to relieve them of any rigorous mental discipline. Professor Babbitt of the College gave a most timely plea for making the test of college preparation a test of mental power.

The evening address by Superintendent Morrison is printed elsewhere in this issue of the MAGAZINE. It was a searching analysis of the present situation as regards the relation of Dartmouth College to the public schools of its own state; it was hopeful, stimulating, and constructive; the speaker showed the fullest appreciation of the work and aims of the College, and at the same time he warned the college authorities that they were facing a new situation, and one which demands new adjustments of college requirements. Some of the adjustments for which Superintendent Morrison argued were already under way and have been adopted since the conference, the others all deserve the most careful consideration of the faculty and trustees. No such presentation of the relation of Dartmouth to its local constituency and to the present problems of the schools has been made, and it is safe to predict that its results will be definite and far reaching.

The remarks of Professor Wicker after the reading of the papers of the evening well supplemented Superintendent Morrison's plea for the closer adjustment of the public school and the college. Professor Wicker argued for a reconstruction of the whole educational system to bring it into accord with modern knowledge and the aims of modern society. Science in its broadest sense must be made the principal instrument of education, and humanity and its social problems must be its central aim. Out of such a system of education will come a real religion of humanity.

The paper by Dr. F. E. Spaulding, Superintendent of the Newton, Mass., public schools, was a most thoughtful plea for the better administration of the schools below the secondary grade. The paper was a fine illustration of the application of sound training in philosophy to detailed problems of pedagogy. The question asked of Doctor Spaulding was how changes' in the work of the elementary schools could be made to relieve the pressure on the secondary schools. In his judgment, based on experiments in the Newton schools, it is not wise to thrust back into the lower schools much if any of the work now assigned to the high schools. The real improvement of the high school is to be sought by making the work of the elementary schools more effective. For this the prime essential is attention to the individual child. Training in masses is ineffective; the brighter children are dulled and stupefied by being held long on work that they have quickly mastered, while the dullest are forced on at a pace that is altogether beyond their capacity; with many of them failure becomes a mental habit. If elementary schools are to do their real work they must have a great reduction in the number of pupils assigned to a single teacher; twenty-five to thirty should be the maximum; the slower scholars ought to be in groups of a dozen for one teacher. Promotion should come to every child whenever he is ready for it, not at stated times in the year, nor together with a class.

Such work demands teachers of the highest quality, and communities must be ready to pay for men and women who are fitted to do this finer work. There is no real lack of financial ability; money will be forthcoming whenever the people as a whole come to value the education of their children as much as they value luxuries like tobacco and alcohol.

The address was one of those simple, far-seeing, reasonable pleas that carry conviction ; no one who heard it can be satisfied with any school that is moving along in a mechanical routine, dealing with children in the mass, and shoving them along from room to room like platoons of toy soldiers on a board. Out of such a system of elementary schools as Doctor Spaulding would have us develop would come high school pupils and college students who would have little complaint to make that college entrance requirements are excessive.

The discussion of Saturday forenoon on effective teaching of science for the two groups of secondary pupils, those who are to go to college, and those who are not, was one of the most profitable of the conference. Professor Bartlett outlined with great clearness the fundamental qualities that should have been acquired by a student who enters college with science as a part of his preparation; they are intellectual honesty, respect for facts and their consequences, power of concentration, and thoroughness. He then spoke in some detail of the essentials of a preparatory course in chemistry; these he stated to be everyday familiarity with a few chemical substances, and that in an orderly way; accurate knowledge of certain formulas, and complete connection in thought between the formula and the substance; some idea of the analogies of formulas and of the making and formulation of chemical equations, with the ability to write them from memory; to this should be added the ability to read the more difficult equations. Arithmetical problems should be simple enough to keep the attention on the chemical rather than the arithmetical relations of the problems; a glossary of chemical terms should be thoroughly mastered. In the case of familiar chemical substances beginners should give more attention to their uses than to complicated processes of manufacture.

Mr. F. M. Howe, instructor in science in Kimball Union Academy, in discussing the training in science needed by the student who is nut to go to college, urged that science courses be made more flexible. Mr. Howe would have the fundamental principles of the science as thoroughly taught to these pupils as to the others, but he would seek the illustrations and applications of the principles in the immediate environment of the pupils far more than is ordinarily done. The course for the city scholar should be very different from that for country schools. Elementary scienceshould be for every student the simpleexplanation of the phenomena with whichhe is himself familiar. There is danger of making the elementary courses in science too mathematical.

In the discussion that followed, stress was laid on the fact that there is no easy way to get scientific knowledge, and that fundamental principles must be mastered before the simplest phenomena can be understood. The belief was expressed that mistakes in the method and aims of elementary science teaching have made it less attractive and less useful in the schools than it was at an earlier period. The remedy will lie in the union of the aims and methods presented by Professor Bartlett and Mr. Howe, between whom there was no disagreement as to principle or method,

Professor Taylor's presentation of the question of the effect of requiring Latin of all candidates for admission to college was based on a large number of letters from members of the Dartmouth faculty in answer to the question of the probable effect in their own departments should such requirement be made. All but two expressed a decided conviction of the great value of Latin as a preliminary discipline. Professor Taylor emphasized the value of Latin as a continuous and rigorous discipline, greatly superior to a combination of single years in unrelated subjects. In the discussion that followed, Principal Young, of the Stevens High School, Claremont, gave strong testimony to the value of the training in Latin, but expressed his conviction that with good teaching as good results may be obtained through an equally extended course in one of the modern languages. He also said that in every school one would find a considerable number of pupils who have no aptitude whatever for Latin, but whose ability in other directions is such that they certainly ought to go to college. He pointed out the fact also that not infrequently a scholar decides late in his school course that he will go to college; one. who has not had Latin, but has been well trained in other subjects, ought not be forced to delay his college entrance while he makes up the work in Latin.

The effect of the discussion as a whole was to emphasize the wisdom of urging scholars who have linguistic aptitude to make Latin a part of their preparatory training, whatever may be their chosen line of after work, and at the same time to show that it is desirable that at least some of the colleges offer admission without Latin.

The social features of the conference this year were unusually enjoyable. A considerable number of the faculty with their wives responded to the invitation to meet the teachers in an informal social gathering at College Hall after the exercises of Friday evening. Singing by the glee club, and refreshments served by the College Club, added to the pleasure of the company. The afternoon of Friday was given to the annual luncheon of the High Schoolmasters' Club of New Hampshire. The club, together with all other visiting teachers and members of the college committee on admission and their wives, were guests of the College. The after dinner speaking was in charge of Principal Tracy of Kimball Union Academy, the president of the club. Dean Emerson gave a graceful welcome to the club, and then two addresses were given by members of the last legislature of New Hampshire, Mr Buffum of Winchester, and Mr. Clough of Lebanon. The substance of their addresses was a plea for making the education given in the high schools more practical. Singing by a quartet of college students in the course of the luncheon was highly appreciated.

* This system of entrance units was adopted by the Faculty at their meeting of May 23. Their final action had been deferred pending action by the Entrance Examination Board, and the discussions of the May Conference.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIN WHAT PARTICULARS DO THE DEMANDS OF THE COLLEGES HINDER THE WORK THAT THE HIGH SCHOOLS SHOULD BE DOING FOR THE PEOPLE AS A WHOLE?*

May 1909 By Henry C. Morrison -

Article

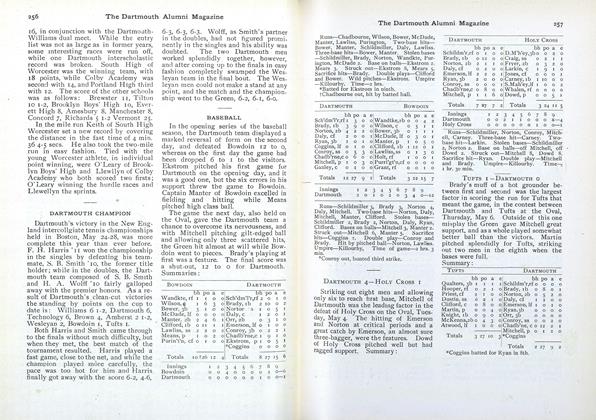

ArticleBASEBALL

May 1909 -

Article

ArticleTRACK

May 1909 -

Article

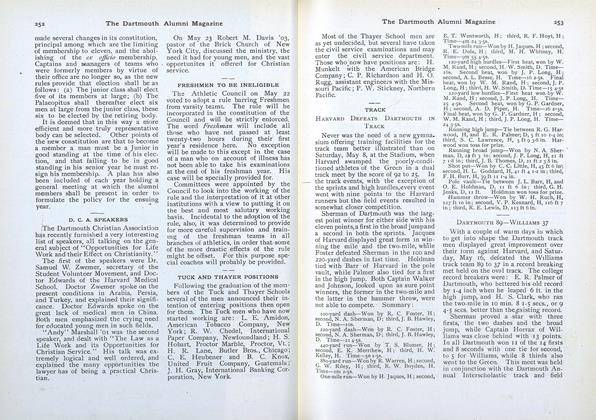

ArticleAt a meeting of the Trustees

May 1909 By W. J. TUCKER -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

May 1909 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

May 1909

Charles D. Adams

-

Article

ArticleRESOLUTIONS ADOPTED BY THE DARTMOUTH FACULTY

DECEMBER 1926 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksGreat Companions.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksGREEK THOUGHT IN THE NEW TESTAMENT.

AUGUST, 1928 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksHISTORY OF AMERICAN ORATORY

November 1928 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksA SON'S PORTRAIT OF FRANCIS E. CLARK

February, 1931 By Charles D. Adams