George Holley Gilbert '78. New York, Macmillan, 1928. Pp. 216. When the Class of '78 received their diplomas in the College Meetinghouse fifty years ago, their outstanding scholar was George Holley Gilbert. When they returned for their semi-centennial in June of the present yearwith all their honors, and they were many and distinguished—, there was no question that the quiet, modest man who was their one-time leader in scholarship was still in the same place. The publication of his Greek Thoughtin the New Testament at the beginning of this anniversary year crowns a series of scholarly volumes, each of which has been an honor to the College.

For a time Dr. Gilbert held a professorship in Chicago Theological Seminary, but as controversy waxed hot in his chosen field of New Testament criticism, his modest and non-combative nature impelled him to cut loose from the trammels of institutional responsibility, and he retired to a quiet Vermont village, where he was free to study and to write with an eye single to the truth as he saw it. His last volume is the natural and rich outgrowth of earlier studies in the life of Jesus, of Paul, in the teachings of the early interpreters of Christianity.

In the past fifty years we have had a multitude of special studies in the New Testament, led by the German specialists; out of these studies has grown a considerable consensus of opinion as to the origin and reliability of the New Testament writings. Dr. Gilbert, thoroughly at home in this critical field, and a valuable contributor to such studies, gives us in this volume an admirably clear and concise statement of the grounds for each position which he takes. Entirely free from the polemic spirit, with utter fairness in the statement of evidence, he is willing to state with entire frankness views which are flatly contradictory to many of the teachings of the churches of a half-century ago, as well as to those of the "fundamentalist" group of today. He is happily free from the tendency of a good many preachers of the advanced group to try to minimize or gloss over the significance of the new views. He does not present a contradiction in the pleasant guise of a "reinterpretation." In fact this volume is an admirable introduction both to the method and the results of scholarly New Testament criticism. Dr. Gilbert's sole purpose is to help restore to the Church the historical Jesus and the essence of his gospel. If the book is destructive, it is destructive only of human and fallible traditions and philosophical theories; it is thoroughly constructive in its clearing of our vision of Jesus and his teachings.

Jhe truth is that in the past century the science of historical criticism—a science that is just as severe and rational in its methods as are the natural sciences, has achieved results quite as important in the study of the New Testament as are the results of Geology and Biology as related to the Old Testament; and its results are as much more important as the New Testament teaching of the way of spiritual life is more important than the account of the origin of physical life "in the beginning." How far this historical and literary critical science has gone, and how deeply it cuts into traditiona views, what havoc it makes with some of our cherished creeds, and on what rational foundation these results rest, the reader of Dr. Gilbert's volume will see with great clearness. He will also see how entirely consistent it is with vital Christianity, and how it strengthens its hold on the thinking man of today.

Introductory chapters on the Hellenization of the Jews and the Greek Environment of the Apostolic Church show how constantly and deeply the Jewish world in the time of Jesus was influenced by Greek ideas. "First, there was the invasion of Palestine by Greek settlers, and second, the dispersion of Jews throughout the Greek world" (and the Greek world of that day was not simply little Greece, but the whole vast empire of Alexander.) To the Jews of the dispersion especially the learning of the Greek language was a necessity, and to all intellectual circles some knowledge of Greek literature and philosophy was inevitable. These hellenized Jews reacted constantly upon'those of the home land who were in only a lesser degree under Greek influence. As to the Apostolic Church, its environment was largely Greek; Greek was from the first "the predominant tongue m which the Church itself read its Gospel, confessed its faith, and sang its praises unto God."' Most important of all were the Greek philosophical and religious ideas with which the early Church was in constant contact. "To suppose that the Church was like a water tight ship in the vast sea of Greek thought and life, that its doctrines were altogether unlike the' religious and philosophical views of the world around, is to shut one's eyes to obvious processes of life, and to make the interpretation of the New Testament in no slight degree an impossible task." The chapter on Greek Thought in the Letters of Paul is introduced by the remark that "a Jew who spent his boyhood in a brilliant center of Greek culture and who, in his mature years, when a Christian, gave himself sympathetically to a religious mission among Greek-speaking peoples, constitutes, a soil in which we rightly anticipate deep marks of Greek influence. Paul felt divinely called to this Gentile field, "which, for the original apostles, appears to have had no attraction whatever."

In his conceptions of the one God, Paul "is at times more Greek than Hebrew." "The conception of God as imminent throughout the universe, an all-encompassing presence, the environment even of our physical being, springs from Greek philosophy. As to Paul's thought of Jesus, "It seems quite clear to the student of today that Paul's conception of Jesus, which is surely of the very substance ot his gospel, was essentially determined for him by a long series of Greek thinkers. The character of Jesus, in the apostle's thought, is divine love, and to that extent he is fully m accord with the story of the gospels, but when we hear him speak of the nature of Christ, his relation to the universe and to God, and his work 'of redemption, we are no longer in Galilee with Jesus, but in a realm of thought altogether foreign to his." Such foreign conceptions are those of Christ as the being through whom Creation took place, as a being who in his pre-earthly existence might have claimed equality with God, a being wo, equally with God, is the source of Grace, a being to whom the apostle offers prayer, and in whom finally all things shall be summed up. The kinship of these ideas is not with the teachings of Jesus himself, but wit Greek philosophy in its Alexandrine form. Gilbert finds the closest relation between views such as these and the teachings of Paul s Jewish-Alexandrine contemporary, Philo. It seems beyond question that the conception of the Logos which is so clear in Philo, is the basis of much of Paul's conception of Christ. Paul attempts to "articulate Jesus in a cosmical system of thought." Thus an ancient stream of Greek speculation, beginning as far back as Heraclitus, became confluent with the simple historical tradition of Jesus, but it is impossible that' they should ever blend," As to the incarnation and redemptive work of Christ: "The nucleus of the popular (Greek) cults of Attis, Osiris and Adonis, is this: A divine being comes to earth, assumes human form, dies a violent death, rises, and through union with him, variously brought about, men are redeemed. And what does Paul teach? A being who existed in the form of God appeared on earth in the likeness of sinful flesh; was crucified, and rose from the dead. Men, through their relation to this experience of a celestial being, are redeemed. The broad similarity is obvious. It will readily be granted that Paul transformed this Greek conception of the method of salvation, that he purified it from much that was crude and unworthy, and that, above all, he threw around it the light of divine love, both the love of Christ and the love of God. This was the contribution of his religious genius."

Discussing Paul's views of the Christian sacraments, Dr. Gilbert remarks that Paul gives little space to them in his writings, and seems to have laid less stress upon them than one would expect in a man of his time, but he feels competed to say that "Paul's view of this subject was foreign to the thought of Jesus." Dr. Gilbert holds that Jesus' own teaching and practice with regard to admission into his kingdom are positively opposed to the sacra- mental view of baptism, and that while Paul's own view is not definitely sacramental, it does tend in that direction. As to the Lord's Supper, Dr. Gilbert does not find evidence that Jesus instituted it as a continuing rite, while he finds Paul's view of the significance of the Sacrament to be closely related to the sacred meals of contemporary non-Jewish cults, like those of Dionysus and Mithra. In this much discussed field one may question whether Dr. Gilbert does not argue too much from the silence of the synoptic tradition, and give too little weight to the probability that Paul's account of the Last Supper was derived from eyewitnesses. The statement of Paul (Gal. 1, 11-12) that he did not receive his "gospel" from man, but "through revelation of Jesus Christ," ought not to be so interpreted as to preclude Paul's reception of many of the facts of Jesus' life from the disciples. It is unthinkable that he did not. It is more reasonable to interpret his word "gospel" in the often quoted passage of Galatians as meaning his conception of the significance of the life and death of Jesus, his Christology, which was, indeed, the center of his teaching. When Paul gives us an account of definite acts and words of Jesus we have good reason to believe that his sources are as trustworthy as those of Mark or Luke.

Paul's use of allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament Gilbert finds to be in line with Philo's practice and that of other contemporaries; so far as these writers are Jews, they have been influenced by Greek writers, notably the Stoics.

In general Dr. Gilbert holds that Paul's partial substitution of a gospel largely the outgrowth of Greek religious and philosophical ideas, for the very simple gospel of Jesus was the beginning of an unfortunate process which gave to the church, century after century, even down to our own time, an Alexandrian Christ, in place of the historical Jesus of Nazareth.

In beginning the discussion of the synoptic gospel Dr. Gilbert reminds us that while Jesus himself seems to have been wholly uninfluenced by Greek thought, though he lived wholly within a horizon of Jewish ideas, the writers of the three gospels were not so situated. They were under the influence of men and women who had separated themselves from temple and synagogue who were building up a new organization, and whose "chief practical problem was how to fit their Jewish Gospel to the Gentile world. In view of these facts the historical student is not surprised that the synoptic Gospels contain material which is not altogether in harmony with the revelation in Jesus, nor is he surprised even when he sees that the words and acts ascribed to Jesus were sometimes modified in transmission before they were finally cast in that literary form in which we have received them. Such results were inevitable, and the wonder is that they were not more numerous."

The space of this review , does not allow detailed account of the foreign elements which the author finds in our Gospels. Among them are the Virgin Birth, which Dr. Gilbert discusses in full detail, the rending of the veil of the temple at the time of Jesus' death, Peter's attempt to walk on the water, the silver coin in the mouth of a fish. Greek influence is distinctly to be seen in Matthew's use of the Old Testament, involving "a misunderstanding of the fundamental character of the prophetic writings." The concluding paragraph of the Gospel of Matthew, with its "world commission" and its baptismal formula, the author believes to be no part of the genuine tradition, but the product of later thought and practice, under Greek influence.

Greek influence in the Acts is especially to be found in the unhistorical account of the Ascension, and of the miraculous 'tongues' of Pentecost.

Dr. Gilbert finds Greek influence in First Peter, but to a limited extent. The story of Jesus' preaching to the "spirits in prison he attributes to such influence, reminding us of the Greek stories of Orpheus and of Odysseus.

A special chapter is given to the Epistle to the Hebrews, which, "the stateliest piece of composition in the New Testament, may be compared to a temple whose frame and structure are Greek, but whose atmospnere is partly Christian?' Dr. Gilbert closes his discussion of Hebrews with these words: "Its conception of Christ is wholly interpenetrated with the widely current views of the Logos; its conception of a heavenly tabernacle of which the Mosaic was only a copy and shadow is based on the Platonic theory of Ideas; and its conception of Scripture is Greek in the underlying view of inspiration, Greek in that Christ is sometimes represented as speaking in the Old Testament, and Greek in its profoundly allegorical character."

In the Fourth Gospel the doctrine of the Logos carries us at once into a field of contemporary Greek and Greco-Jewish thought, for the doctrine does not spring from a Jewish root. Other Johannine ideas are connected with this. Such is that of the supernatural knowledge possessed by Jesus, a conception which "is irreconcilable with the view of the earlier evangelists and the view of Jesus himself as contained in the synoptic narratives. Jesus is there represented as having a veritable human consciousness with respect both to knowledge and power." Teaching which John ascribes to Jesus as to the of his own knowledge, "that is, his attainment of it m a heavenly state" before his human birth, is a corollary of the doctrine of the Logos.

The Jesus of the synoptic Gospels is a Jew, speaking usually with in mind; but in the Fourth Gospel "the national character of the work of Jesus is well-nigh lost in its universal character. He no longer talks as a prophet of Israel, but only as the Light of the World." This conception too is a corollary of the doctrine of the Logos. Still more important is the difference between the mediatorial work of Jesus as taught in the synoptic Gospels, as for instance in the parable of the Prodigal Son, and that of the Fourth Gospel, where the Logos, in the full Greek conception, mediates between man and a transcendent God.

In his final chapter, "Conclusion," the author reviews the results of the foregoing studies, declaring that the Greek element in the New Testament must be judged wholly upon its own intrinsic worth, not regarded as_ authoritative because of its having been admitted into the body of our gospels and epistles. A few Greek elements are in general agreement with the primitive gospel, though lying beyond its horizon; still others, and those the most conspicuous, deal with subjects vital to the primitive gospel, and yet they are incompatible with it. "The primitive historical revelation in Jesus is indestructible because it is found true and priceless in human experience, jhe purest and highest truth that man knows."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNOFFICIAL AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

August 1928 By Robert Davis '03 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

August 1928 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1928 -

Sports

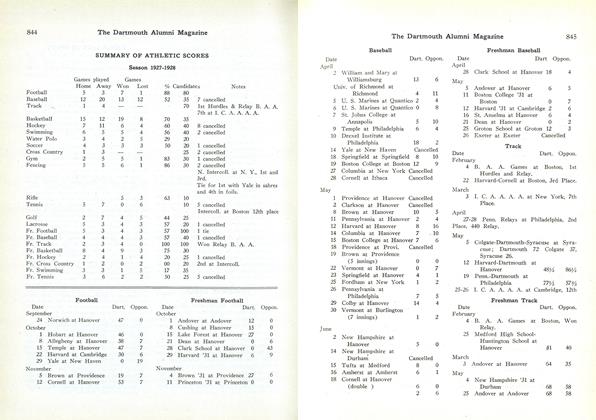

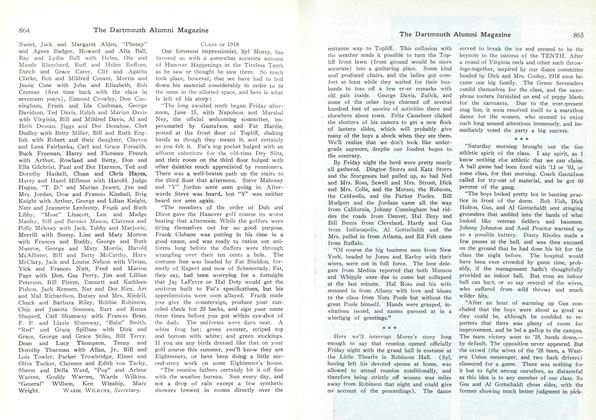

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

August 1928 -

Article

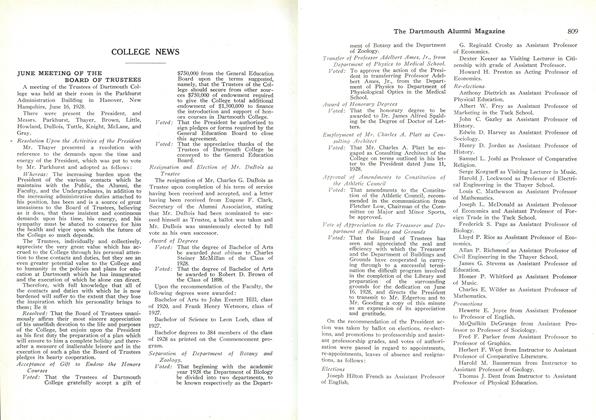

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

August 1928

Charles D. Adams

-

Article

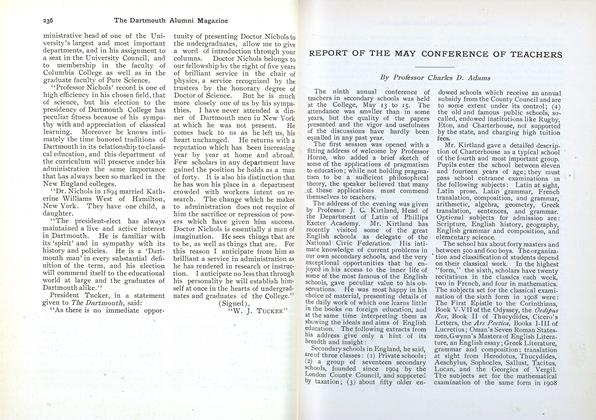

ArticleREPORT OF THE MAY CONFERENCE OF TEACHERS

May, 1909 By Charles D. Adams -

Article

ArticleRESOLUTIONS ADOPTED BY THE DARTMOUTH FACULTY

DECEMBER 1926 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksGreat Companions.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksHISTORY OF AMERICAN ORATORY

November 1928 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksA SON'S PORTRAIT OF FRANCIS E. CLARK

February, 1931 By Charles D. Adams

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE FRENCH REVOLUTION

February 1933 By Frank Maloy Anderson -

Books

BooksTHE RESTLESS HEART: BREAKING THE CYCLE OF SOCIAL IDENTITY.

March 1974 By H. GAYLORD HITCHCOCK'66 -

Books

BooksPEPPERFOOT OF THURSDAY MARKET

June 1941 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksGEORGE GASCOIGNE,

March 1942 By Lucien Dean Pearson -

Books

BooksA PERSONNEL PROGRAM FOR THE FEDERAL CIVIL SERVICE.

MARCH 1932 By MIlton V. Smith -

Books

BooksNEW YORK IN THE CRITICAL PERIOD,

March 1934 By Wayne E. Stevens