by Warren Choate Shaw '10. Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill Co. 1928. Pp. XI, 713.

In his preface Professor Shaw says that this volume "is intended primarily for use as a school and college text-book in public speaking courses; but it should also prove interesting and valuable to the general reader and especially to all students of American history; for, in a sense, the history of American oratory is the history of the American people, a record of their thoughts, feelings, passions and ideals, in every important period and crisis through which the nation has passed." The author attempts to provide "for teachers and students of oratory just such a background of history as is provided so lavishly for teachers and students of composition and English literature in its written form." Professor Shaw gives this statement of his principal objectives: "To provide the student of public speaking with a vast body of historical information suitable for use in speech-making; to stimulate him, at every turn, to undertake independent research for further interesting and valuable information suitable for use in speech-making; and to give him a course in speech-making, built upon materials contained in, or suggested by, this text, which will develop all his latent powers for strong and original speech-composition and speech presentation."

American oratory is treated under captions of successive periods, a brief statement of the significance of the period being given, with summary mention of its leading orators. Then follows a "life" of each of the orators chosen as representative of the period, a rather extended account of the circumstances of a selected speech, and some characterization of it, and finally an extract from the speech itself. Then is given a generous bibliography for collateral reading both for the period and the chosen orator, including many of the principal speeches; to this are added suggestions for collateral studies on the speech-texts included in the volume, and "dictionary studies", on words found in the extract.

These historical introductions to periods of oratory and the biographical accounts of the men show most exhaustive labor, skillful condensation, and a fine appreciation of what is needed by the student. The accounts are wonderfully comprehensive, considering the necessary limitations of space, and they are interesting. A reader finds himself impelled to follow the suggestions of the bibliography, and read the whole speech. Professor Shaw gives more attention to the historical and biographical material than to the appreciation and criticism of style. Characterizations of style are of course not lacking, but there is seldom any detailed treatment or criticism in this part of the field. We should expect in the introduction to each "period" some statement of the type of style prevalent in that time, and some attempt to relate it to the general tendencies of prose writing in that period; and it would be most useful to trace the influence of contemporary English style on that of American writers. For style is as much a part of an oration as subject-matter is, and the successive periods of American oratory show marked progress in the development of a clear, simple, yet impressive rhetorical style.

The orators chosen for extended treatment in this volume are those best known by tradition. Greek criticism had a "canon" of ten orators; Professor Shaw finds twenty-one for the United States. Bryan, Beveridge, and Wilson are the latest. Political orators are in the great majority. But Wendell Phillips, Beecher, and Ingersoll are representatives of the orators of the "special occasion"—the panegyric, the eulogy. The pulpit is not very generously represented in this volume. Professor Shaw admits the great power of the pulpit in the colonial period, but he says that "such eloquence was in no sense characteristically American," and that it "left no permanent literature that is capable of stirring the hearts and souls of modern generations." But as regards style, American pulpit oratory in the early period was no more under the English influence than our political oratory was in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As regards the possibility of stirring the feelings of later generations, that is not the test of oratory, but its power to stir the minds of the men of its own time. To men who believed profoundly that great masses of men were doomed to the fires of hell, Jonathan Edwards and the men of his time spoke with tremendous effect. That oratory must be included in any complete survey of American eloquence.

Dartmouth men will turn first to Professor Shaw's treatment of Webster and Choate; and they will not be disappointed. His treatment of the political questions of the period is full and discriminating, much of this matter being involved in his discussion of the lives of Clay and Calhoun. The discussion of the oratorical style of Webster is greatly enriched by the inclusion of Choate's tribute in the Eulogy delivered in the old College Church, while the cruel injustice which Webster suffered in his later years is vividly presented in the extract from Theodore Parker's terrible discourse on the death of Webster. The selections from Webster's orations are well chosen, including representative extracts from legal oratory, eulogy, and parliamentary debate. One of the few extracts in the volume representing descriptive oratory is from Webster's speech in the White Murder Case, one of the great descriptions of all time. To the Webster bibliography might well be added President Felton's great tribute, shortly after Webster's death, a discussion of Webster's statesmanship and oratory by one of the ablest critics of the time (AmericanWhig Review, Dec. 1852).

In the discussion of the oratory of Choate there is much of sound criticism. An old classical teacher would like to find more attention given to Choate's life-long study of prose style in Latin and Greek writers and especially to his early morning readings, in Thucydides and Demosthenes, while he was in the United States Senate. Webster's oratory was always under the strong influence of the Ciceronian style of Edmund Burke. If Choate was Webster's superior in refinement of style, it may well have been due to the fact that he had made more systematic and mature study of prose style in general. There are parts of Choate's journal which ought to be made required reading for every college student of oratory.

It is a far cry from Webster and Choate to Bryan; but if oratory is to be judged by its effect on the hearers, certainly Bryan deserves the place which he receives in Professor Shaw's volume; and the characterization of his oratory, while brief, is just and satisfying. If Choate was the ripe product of classical training at its best, Bryan was the fruit of the mid-west college debating society and intercollegiate oratorical contest, so far as style and manner are concerned; but back of the style there was a fine manhood, which made his life one of chivalrous, if futile, efforts for ill-conceived ideals.

We should have welcomed a final chapter in which the author might have summed up the characteristics of American oratory and compared it with that of England and France, but where he has given us so much it would be captious to demand more.

A series of appendices gives various pedagogical suggestions—Vocabulary-building, Pronunciation and Enunciation, Delivery, etc. At the close of the chapter on each orator a list of words is given which the student is advised to study in his dictionary. As Professor Shaw has taught both at Dartmouth and Knox, one must be reticent as to this list; but it is to be hoped that it is only at Knox that college students need a dictionary for, let us say, "absurd, hypothesis, unsullied, taunt, faction;" still, even a brainy Dartmouth aristocrat may find a dictionary useful for derivations even of these!

A word should be added about the questions on the text which follow each extract. These are certainly an "intelligence test": questions as to literary, especially Biblical, allusions, historical references, etc. Here again the reviewer misses questions that have to do with style, or that might point out passages where the eloquence becomes grandiloquence, as in the closing sentence of Wendell Phillips' Toussaint L'Ouverture.

The limits of even this portly volume forbade the printing of any important speeches entire. Professor Shaw tells the student where he will find them, and the wise teacher will surely insist that some at least be read throughout, their argument analyzed, and their style criticised. No study of extracts can take the place of such discipline. The reviewer does not know to what extent inexpensive editions of single speeches, with rhetorical and stylistic criticism, are available. If there are not such for most of the great speeches, he hopes that Professor Shaw will make it his next effort to supply them. He will then have made his apparatus complete.

Teachers and students of American oratory have reason to be grateful to Professor Shaw for having collected for them such a mass of material, historical and political, as well as biographical, and having presented it so clearly and in a manner so attractive; and others will find it an invaluable book of reference. The book does credit to Dartmouth and to Knox.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis New Library

November 1928 By Henry B. Thayer, '79 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1914

November 1928 By John R. Burleigh -

Article

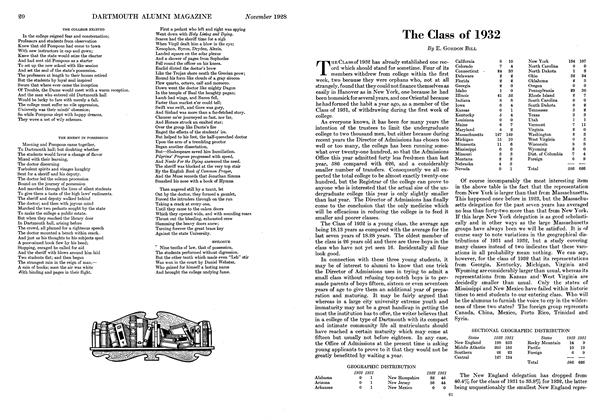

ArticleThe Class of 1932

November 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Lettter from the Editor

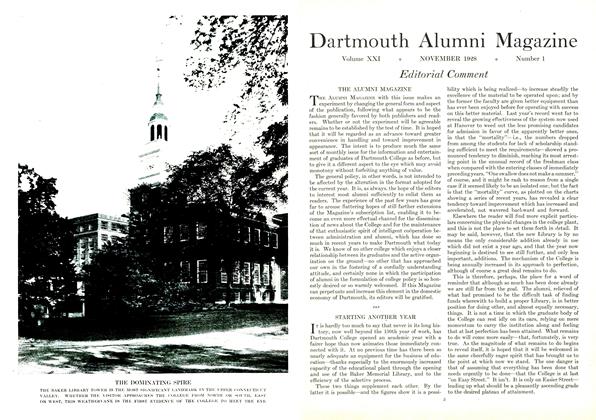

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

November 1928 By Charles D. Webster, Air Reduction

Charles D. Adams

-

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE MAY CONFERENCE OF TEACHERS

May, 1909 By Charles D. Adams -

Article

ArticleRESOLUTIONS ADOPTED BY THE DARTMOUTH FACULTY

DECEMBER 1926 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksGreat Companions.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksGREEK THOUGHT IN THE NEW TESTAMENT.

AUGUST, 1928 By Charles D. Adams -

Books

BooksA SON'S PORTRAIT OF FRANCIS E. CLARK

February, 1931 By Charles D. Adams

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

NOVEMBER 1970 -

Books

BooksROME

MARCH 1967 By DAVID SICES '54 -

Books

BooksFINLAND ON FIFTY DOLLARS

October 1938 By Harold G. Rugg '06 -

Books

BooksTHE NAKED WARRIORS.

November 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLaw of the Jungle

NOV. 1977 By JOHN S. RUSSELL JR. '38 -

Books

BooksBACKFIRE

JUNE 1932 By R. L. Woodcock