[The following address was delivered to the Class of 1899 on the occasion of its fifteen-year reunion. It is printed here as an interpretation of the reasons for Dr Tucker's remarkable personal influence.—EDITOB.]

Mr. Toastmaster, it would be difficult for me to respond to my toast in a humorous vein. Grant me, Sir, a special privilege tonight to speak somewhat in a serious mood. You may count upon the other speakers to make amends for my fall from grace.

We of '99 were fortunate enough to pass our entire college course under the direct personal, influence of William Jewett Tucker. It seems good, to me it seems no usual thing, for us to meet again and talk over our indebtedness to Dr. Tucker, which the intervening decade and a half has taught us to be much greater than we once realized. We one and all regard him with a sentiment akin to filial gratitude. We honor and love him for the message that he gave us and for the man that he is. Rather than reciting anecdotes or pronouncing a eulogy, let us try something more fundamental this evening, let us try, if we may, to refresh our memory as to his thrilling message and the inspiring personality out of which it issued.

0, how we: would like to hear his voice again that used to convey to us the message,—a voice so expressive of moral courage and spiritual passion, so fearless, so challenging, and so tender! 1 am afraid we shall never again hear that voice in public. Fortunately, it is possible for us to read some of his published works, especially his "Personal Power," and through his remarkably clear and vigorous style to recall most avidly the voice, the message, and the man. Read them, if you will, no longer with a passive mind, but in the light of the experience and insight you have gained during the fifteen years of contact with the world. Then, perhaps, the message will strike in you a deeper note of response than you may imagine. You will also get a rare opportunity to take a measure of yourselves,—a thing which you and I must do from time to time, if we would grow as men.

What was William Jewett Tucker's message to men of Dartmouth, not in its detail, but in its very essence? I believe it was through and through a moral message. "Seek, I pray you," said he, "moral distinction. . . . Do not expect that you will make any lasting or any very strong impression on the world through intellectual power without the use of an equal amount of conscience and heart. The laws of your being are against the experiment. Accept the moral law as you accept the law of gravitation." And his moral teaching was specially adapted to the needs of the age in which we live. Here, as in every other great' phase of his college administration, Dr. Tucker seems to have begun his work with a definite, clearly conceived policy or principle. It would seem that he had perceived, in his very lively appreciation of the active movement of social life in America, that there existed a double, self-eontradictory tendency, to fall back, on the one hand, more heavily than before and increasingly upon the sense of individual responsibility of the educated person, and, on the other, to relax the moral stimulus of the home life and to develop complex impersonal contacts in society. Between these conflicting tendencies, the college education, as Dr. Tucker conceived it, was set for the task of "quickening the personal power" of the student,—that is, to help him find himself in full measure, to kindle his sense of responsibility and, perhaps, consecration, and thus to send him out into society as a free, loyal, and undaunted moral being,—as a nucleus of clear, vitalizing power working in the midst of the confused and distracting society.

Upon this basis, Dr. Tucker inculcated a number of obligations the college student owed to society, and his discussion of each was original and stimulating. But his message was not a mere catalogue of social duties; it had a distinct unity. It seems to me that its basic principle was the fundamental capacity of man for truth, and the honest action that would result from the development of that capacity. Do you not recall how" often Dr. Tucker emphasized the isolation and the ultimate defeat of the untrue man,—the man, that is, who was not whole, who was willing to "take his chance as to the powers within him, whether they would work true or not?" Still oftener did he lay stress on the true man, honest and straight man, who, he stated, would gain "contact, influence, power as touching man, oneness with all related life, access to Nature, communion with God." And when one was filled with that power of truth, and saw in all other men the same capacity for truth, then he would act; he would "rise to the plane where he belonged," to use Dr. Tucker's expression, "the plane of leadership or of service." Till one came to honest, positive action, his power was merely potential. Action was the end; action was the "moral maturity" of the man. For the same reason, action meant, also, "the going out of self into men's lives." In other words, action was sacrifice, the gift of the costliest, of one's .true life to others' true lives. To this consummation should the realization of the universal capacity of men for truth lead. "You have yet to learn the art of giving," said Dr. Tucker; "Be patient with yourselves. . . The art of giving is learned by much practice, and through some mistakes. The only fatal mistake lies in not giving enough." Is not this a dynamic message? Can we remind ourselves of it too often?

Notice, friends, how our teacher put the whole idea in the form of a law, inexorable moral law. Hence the authority of the message. Integrity is a law of humanity in action. That, and nothing short of that, is in all men; it and it alone finds response in all men. "Keep your faith, I pray you, in men," said Dr. Tucker; "Use the true, never the false, in human nature, and persist in doing this. So shall you gain access, every one of you in his own way, to the heart of humanity. So too shall you get your return from the heart of humanity. Action and reaction are equal in the moral as in the physical world."

So much for the message. Now, does it seem presumptuous of me, my friends, to seek to return from the message to the man himself, to the author of the message? Would we not know, if we could, the source of his moral power from which sprang so challenging a message? In his intellectual life, Dr. Tucker showed few of the signs of that rigidity of the mind which is already upon most of us as we barely enter our middle life, but seemed always open to new light and ready to revise his views; even his present life in retirement he has characterized as "most stimulating and quickening. Perhaps as remarkable, if we only could see it, is his growth in spiritual grace. Where is the fountain of life from ' which he appears always to have drawn and still to draw? Is it within our power, even in the smallest measure, to share the blessing?

I trust it is no breach of confidence to say, for tie himself Has said it in public mat, toward the end of his seminary course at Andover, Mr. Tucker, then a young man 01 twenty-seven, hesitated awnne between the law and the ministry. Among the things that definitely committed mm to the ministry was a letter written by Frederick W. Robertson to a Friend in 1849 in which that noble English preacher expressed his passionate love of Christ. May I read a lew sentences from Robertson's letter which inspired the young Tucker and helped him to decide so large an issue? You will admit, in the light of his later career, that the issue has proved large indeed.

" . . . . Of one thing I have become distinctly conscious," wrote Robertson, "that my motto for life, my whole heart's expression, is, 'None but Christ; . . . to feel as He felt; to judge the world, to estimate the world's maxims, as He judged and estimated. That is the one thing worth living for. To realize that, is to feel 'none but Christ.' But then, in proportion as a man does that, he is stripping himself garment after garment, till his soul becomes naked of that which once seemed part of himself; he is not only giving up prejudice after prejudice, but also renouncing sympathy after sympathy with friends whose smile and approbation was once his life, till he begins to suspect that he will be very soon alone with Christ. More awful than I can express. To believe that, and still press on, is what I mean by the sentence, None but Christ.' I do not know that 1 can express all I mean, but sometimes it is to me a sense almost insupportable of silence, and stillness, and solitariness."

ere was no abstract theological argument, but a real, intense religious passion,-yet a passion based upon a trenchant reasoning. I say, a passion built upon reason, for Robertson had, after a considerable struggle in his mind, come to the simple but compelling conviction that the nature of Christ's mission was wholly sacrificial. Comparing Robertson with Tucker, I cannot help noting two traits of character that are common to both, namely, the far-reaching but wholesome intellectual imagination, and the strong spiritual passion capable of a high degree of devotion. It is not, therefore, difficult to understand that, in the one case as in the other, there was the conviction that the one aim in the search for truth should be reality, and also the convic- tion that devotion to a cause should be so strong and passionate as to involve the element of self-sacrifice. Complete devotion to Christ and the sacrifice of self for the great reality of His loving sacrifice to mankind—l feel quite certain that here is Dr. Tucker's fountain of life. For out of such a pure spring, and out of it only, must flow that most valuable of personal possessions—the spiritual graces and strength and energy that are never dried but increase with the years.

If we were so privileged as to look into the inner process of this mysterious life, I presume we might see that one of its important features consisted in continual reflection in the spirit of humility. Day by day—may I repeat the words? day by day—one's sense of his weakness and unworthiness returns to him, and year by year it gains in force as his searchings of his own heart become more exhaustive and uncomnromising. At the same time, this humble reflection before God keeps him always on the alert for new light and new sacrifice. Selfishness has little chance to invade such a loyal and vigilant soul; it becomes gradually invested with surprising spiritual graces which it is too intent and too humble to ask for.

How many of us realized that, while we were being stimulated by ' Dr. Tucker, he himself was drawing inspiration from his work for us? But how could it be otherwise with so humble a spirit? "No man," said he, "can undertake a great task [in education] in a mood so confident or so careless, that it will not return to him day by day with questions so fundamental and farreaching that he must answer them, if at all, under the very motive and through the very principles which are in their nature religious." "The great fact," he said again, "which confronts the educator day by day is that of capacity, the capacity of the human mind. . . . The educator sees human nature, not at its best, but just at that time when the imagination adds to fact the increment of promise. The very suggestions of power are often startling And if he be a man of reflection, he sees and feels more and more the religious significance of the endowment of . the human race with reason, an endowment which carries with it freedom, the spirit of inquiry, and the glory of personal responsibility in thought and action." So he concluded: "The work of education leads the way as surely as any known work, into the certainty and gladness of faith. It must needs be so. It is work in mind and in truth, the two great realities. The proportion therefore of the permanent in it is very great." So there was give-and-take between him and us ; no doubt he gave us more than we ever knew, and took from us more than we were able to take from him.

I have ventured to refer to this phase of Dr. Tucker's life, in order to round out our survey of the source of his great power for service. That source was, as we have seen, purely spiritual; it was the surrender of self, reverence, and humility, reinforced by his intense nature. The ultimate results of service born of such a source must necessarily far exceed the results that are known to its author. We all carry some of these results. Through us they shall multiply. And in this multiplication should consist the expression of our gratitude to the man and our own service to the world. It is, therefore, fitting to close my remarks with another powerful quotation from his message. With the Biblical text: "Freely ye have received, freely give," William Jewett Tucker said:—

"A man must learn how to give the whole of himself. I count this the secret of all success, as it is certainly the secret of all influence We do not get very far into life until we learn how costly a thing it is to live. The progress of the world is carefully registered, could we but see it, in the expenditure of personal power. 'Freely ye have received'— that means that somebody gave freely, gave of himself to you. 'Freely give'—that means, maintain the great succession. Pass on good gifts to men. Pour out of yourselves into the heart of the world."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePROBLEMS IN PREPARATORY SCHOOL ATHLETICS

March 1915 By Walter H. Lillard '05 -

Article

ArticleThe message of the College does not come to all with the same distinctness

March 1915 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

March 1915 -

Class Notes

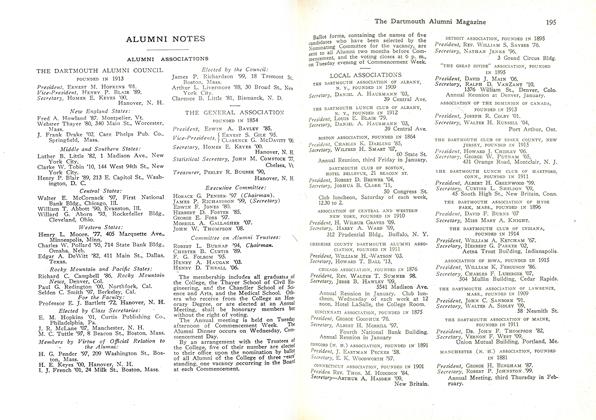

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1915 -

Article

ArticleTWO MEN OF DARTMOUTH

March 1915 By William Byron Forbush '88 -

Class Notes

Class NotesST. LOUIS ASSOCIATION

March 1915 By LEIGH C. TURNER '04