[President Hopkins during his recent trip among alumni associations of the College spoke of course, without notes and varied the emphasis and the nature of his remarks to suit the requirements of each occasion. Yet the theme of his message was everywhere the same, and it is here given in what is, after all, a digest rather than a transcript.]

It is a wise custom that year by year summons the President of Dartmouth out among the graduates of the College, — for whatever they may get from him, he must, of necessity, get much from them. The responsibility of the College at any given time is to the undergraduates of that period, but the reputation of the College at any given time is largely in the hands of the alumni. There is much to be learned, therefore, from studying this finished product of the College, the alumni group. It is likewise its own testimonial to Dartmouth's influence, and the stand of its graduates in the outside world that wherever Dartmouth men go, their influence promptly begins sending other men back for the Dartmouth training.

Three facts about the College are particularly impressive, as one goes from great meeting to great meeting throughout the country,—the distribution of the Dartmouth constituency, its loyalty, and its organization.

The proportion of geographical distribution, both of graduates and of undergraduates, insists upon constant consideration of the fact that Dartmouth is a college national in type to a degree unsurpassed by any and equalled by few. Located, as the College is, beyond the main lines of travel in northern New England, nevertheless, the growth of the College has been largely from without New England's boundaries, while still New England herself, has furnished an ever increasing quota of men. The vision which President Tucker brought with him to the presidency in 1893, of Dartmouth's contributing to the national life of this vast country, as it had in earlier times contributed to the country of nearer boundaries, was largely realized during his own administration, and has shaped the work of the College since, and will continue to do so. And those who are of the administration, or of the faculty, or of the alumni, can take no narrow or provincial view of their obligations to a student body which comes in increasing numbers from the middle and far West, until even now approximately fifty per cent are from beyond New England's areas.

Incidentally, it should be said that, once a college has a sufficient unit upon which to work advantageously, this question of the undergraduate numbers is important as a question of proportions of distribution rather than of size. We have a unit large enough in our fifteen hundred men, and the problem is greater to find the system by which to restrict our growth without breaking contacts with the public school 'system, or impairing other influences that make for our democracy, than is any problem of increased numbers. A man pays $140.00 for instruction which costs the College $300 to give. Its endowments pay $160. An increase of one hundred men costs the College the income on $400,000. Our present funds cannot properly be stretched out to do more work. There is nothing sacred about the figure of fifteen hundred that should make us wish to hold the figures there, . if added endowment comes, but, until such time, it is far more to Dartmouth's interest to have the numbers remain where they are, to restrict the courses in its curriculum and to strive to increase the size of the instruction staff and the financial recognition which the College offers to those capable men upon it.

The late Prof. Royce once gave a series of lectures on the "Philosophy of Loyalty" in which he showed that the great impulse of loyalty in a man's life is a vital need, but that it should be a loyalty to something of the greatest importance, a fundamental requisite, so that some other loyalty of major importance should not come along and crush it, thus decreasing the sum total of loyalty in the world.

I believe it behooves us, as Dartmouth men, to analyze our own enthusiastic loyalty. Is it to a name or to a thing? Upon the answer must rest the opinion of its ultimate worth.

The founders of the historic colleges had just one thing in mind, the production of intelligent manhood interpreted broadly, and I believe that need to be just as great today. It is this purpose transmitted down through the decades, for ISO years and to reasonable extent fulfilled, that commands and gains the loyalty of Dartmouth men to their College, and it must be to convincing work to this end that the College shall continue to point, to win continuing and increasing loyalty, if this loyalty be worth while.

The College of distinctive type, like Dartmouth, must keep its own functions clear in its own mind, for it can not accept the university theory that the development of mentality along specialized lines is its sole responsibility; nor can it accept the theory of the "college-within-the-university" that the college is simply a threshold to the university, and all else is subordinate. The great majority of Dartmouth men, seventy-five per cent, who are deriving their final preparation for their life's work in her halls, precludes the latter, if we are still to claim that our service to them is of particular value.

As a matter of fact, the present tendencies in education are to squeeze the college out of the direct line of educational ascent. The development of Junior Colleges in the public school systems of the country, covering the first two years of college work, will be met eventually, I believe, under the demand that men be introduced to their careers at younger age, by the university's swinging its entrance requirements back, to take men at the close of their junior college work directly into the professional schools and the graduate courses.

What becomes of the traditional, cultural college of unit type, then? —the question arises; and the answer is as plain as the inquiry. It becomes free to develop as a terminal in education rather than as a way-station, and resumes its old-time functions as a shaper of careers, rather than specializing primarily on the needs of the university.

Nothing must be allowed to obscure the primary function of the college to give the zeal for intellectual power which is possible only for trained minds. But accompanying this, the college must assume responsibility for insistence upon the development of moral fibre and the conserving of health in the men entrusted to it at the most impressionable period of their lives. The world at large calls for and demands men of all-round development,—men of brains and character and health. There are the "good" men and these are the traits in men that it is Dartmouth's responsibility to develop.

I know not what other institutions of higher learning may conceive their responsibilities to be, but this is Dartmouth's, the definition of which was given by Eleazer Wheelock and his associates one hundred and fifty years ago, as by the founders of all other traditional colleges of earlier times, and insistence upon which is given by present day needs.

Now, if our loyalty is to this ideal, are we organized to accomplish it, and does our organization work? It can be made to, and it is for this that I am pleading. As alumni, as officers of the College in administration or instruction, and as undergraduates, we must know the College problems and strive without ceasing to solve them. We must be free from that curse of highly developed modern organization which makes a department in an organization seek its own advantage, even at the expense of the welfare of the concern as a whole. It is inconceivable that with intimate knowledge of college problems, there could be any lack of common striving to solve them on the part of any of the great groups of the College constituency at home or abroad. There is no place for ignorance nor for selfishness in the program. Our aim is the development of instinct for the honorable and the spiritual, the intellectual and the healthful in each man entrusted to our care. Our progress towards this goal is dependent upon the paths of our different groups running parallel, and never counter to each other. The star of full accomplishment is sufficiently remote so that if we keep our eyes toward this we shall all find ourselves advancing side by side. Appreciation of our function will demand that men on the college faculty be teachers as well as scholars, interested in their students as well as in their subjects and solicitous for the College as well as for their departments of knowledge. It will demand from the undergraduates that they recognize the right of the College to insist upon evidences of worth which shall make its diploma an assertion of positive value rather than a certificate that nothing has been done sufficiently poorly in scholarship or conduct to bring about separation. But as insistently, it will demand from the alumni, collectively and individually, that they bring their great influence to bear, as. they gather from time to time in Hanover, or as they meet men of the College outside, that the purposes of the College shall be understood and accomplished, and that in truth it may be, even as never before, the inevitable producer of the men for which the professions and industry and citizenship are crying,—the "good" men, of character and health and brains.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePresident Hopkins' recent visit among the alumni has proved most gratifyingly successful.

March 1917 -

Article

ArticleTHE GRADUATE CLUB

March 1917 By Harry E. Burton -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE MONTH

March 1917 -

Article

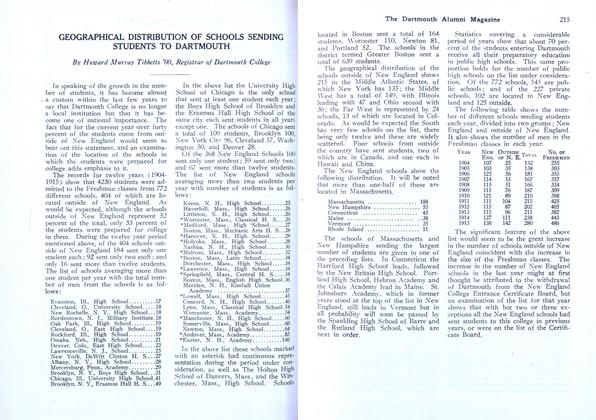

ArticleGEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF SCHOOLS SENDING STUDENTS TO DARTMOUTH

March 1917 By Howard Murray Tibbetts '00 -

Books

BooksSaints Legend

March 1917 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1916

March 1917 By Richard Parkhurst