In October 1994, Dartmouth hosted Lessons and Legacies III: Memory, Memorialization, and Denial, the third phase of an international conference on the Holocaust. I was one of two undergraduates who attended the conference as an official participant. I suppose I was a natural choice for the invitation. Since the age of 13 I have studied the Holocaust, and have visited several former concentration camps in Europe. Still, when the conference began, I felt out of place amidst the crowd of more than 100 scholars. At the first formal dinner I glanced around the table. I was the youngest by at least 15 years.

To my surprise, though, conversation flowed easily. The woman to my right, a professor at Williams, immediately launched into her family history. She told me the story of escaping from Nazi-occupied Vienna to Shanghai, and the difficulty of growing up in the unfamiliar culture.

The woman across the table told of fleeing Warsaw in the 1940s as a young Jewish woman. She described the loss of her home and possessions, as well as the devastating realization that the culture she loved was being destroyed ruthlessly around her.

held me back from participating in the storytelling.

About halfway through dinner, it hit me. The stories that I had been hearing all had a common denominator. Persecution. Es cape. Survival. And my family? My grandparents were among the thousands of German and Austrian citizens who stood by quietly during the Nazi era.

They were never party members, but my grandfather did fight in the German army. My cousins were in the Hitler Youth. My father grew up living in Hitlerbau, a maze of yellow-plastered apartment buildings built by the Nazi government. Throughout the war, my grandparents' home was 15 miles from the infamous concentration camp at Mauthausen. At a table of survivors and children of survivors, I was the granddaughter of people who embraced Hitler.

That evening still haunts me. How can I know the cries of Nazi victims and still take in the quiet rationalizations of my Austrian relatives? Why do I continue to hear whispers of both voices in everyday life?

Dartmouth has provided me with many ways to explore such questions. I participated in the Language Study Abroad Program in Mainz, Germany, and the Foreign Study Program in Berlin. I visited the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., as part of a Holocaust class. I wrote a 60-page journal exploring my reactions to Holocaust material. As the Presidential Scholar research assistant to History Professor Leo Spitzer, I have been working on a study of Central European refugee emigration to Latin America during the Nazi era as remembered in individual and collective memory.

But understanding remains elusive. The methods are so intricate, the faces so ordinary, the horror so absolutely overwhelming. And the fact will always be that my grandparents stand on one side of history, and my conscience on another.

Caught in the middle, I am still searching for answers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

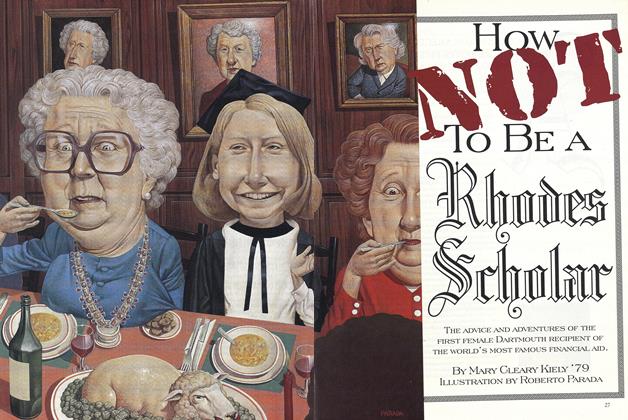

FeatureHow not to Be a Rhodes Scholar

October 1995 By Mary Gleary Kiely '79 -

Cover Story

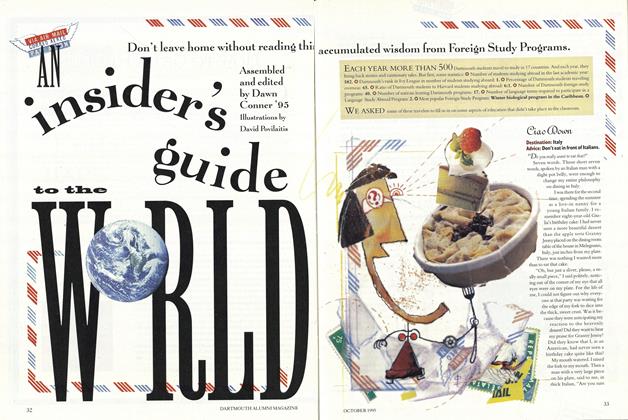

Cover StoryAn Insider's Guide to the World

October 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Feature

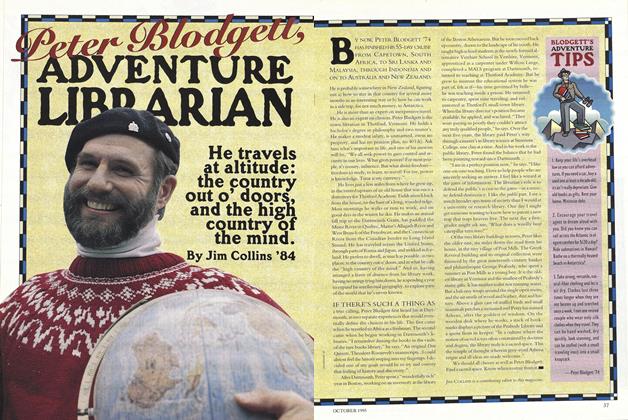

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman