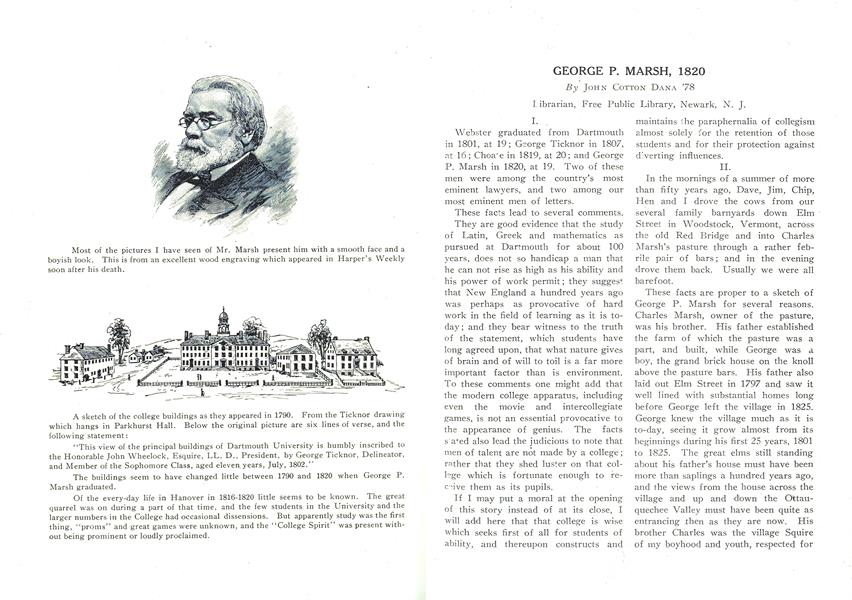

Librarian, Free Public Library, Newark, N. J.

I.

Webster graduated from Dartmouth in 1801, at 19; George Ticknor in 1807, at 16; Choa e in 1819, at 20; and George P. Marsh in 1820, at 19. Two of these men were among the country's most eminent lawyers, and two among our most eminent men of letters.

These facts lead to several comments.

They are good evidence that the study of Latin, Greek and mathematics as pursued at Dartmouth for about 100 years, does not so handicap a man that he can not rise as high as his ability and his power of work permit; they suggest that New England a hundred years ago was perhaps as provocative of hard work in the field of learning as it is today ; and they bear witness to the truth of the statement, which students have long agreed upon, that what nature gives of brain and of will to toil is a far more important factor than is environment. To these comments one might add that the modern college apparatus, including even the movie and intercollegiate games, is not an essential provocative to the appearance of genius. The facts stated also lead the judicious to note that men of talent are not made by a college; rather that they shed luster on that college which is fortunate enough to receive them as its pupils.

If I may put a moral at the opening of this story instead of at its close, I will add here that that college is wise which seeks first of all for students of ability, and thereupon constructs and maintains the paraphernalia of collegism almost solely for the retention of those students and for their protection against diverting influences.

II.

In the mornings of a summer of more than fifty years ago, Dave, Jim, Chip, Hen and I drove the cows from our several family barnyards down Elm Street in Woodstock, Vermont, across the old Red Bridge and into Charles Marsh's pasture through a rather febrile pair of bars; and in the evening drove them back. Usually we were all barefoot.

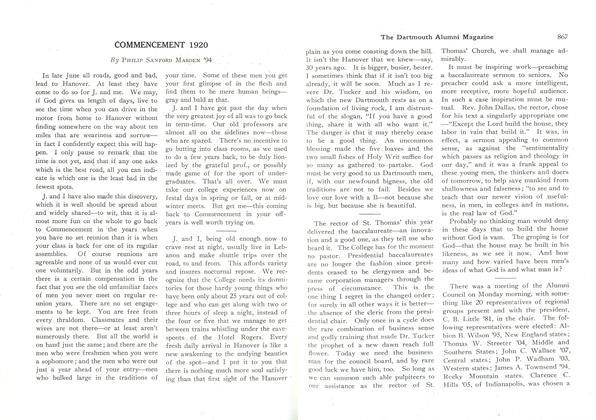

These facts are proper to a sketch of George P. Marsh for several reasons. Charles Marsh, owner of the pasture, was his brother. His father established the farm of which the pasture was a part, and built, while George was a boy, the grand brick house on the knoll above the pasture bars. His father also laid out Elm Street in 1797 and saw it well lined with substantial homes long before George left the village in 1825. George knew the village much as it is to-day, seeing it grow almost from its beginnings during his first 25 years, 1801 to 1825. The great elms still standing about his father's house must have been more than saplings a hundred years ago, and the views from the house across the village and up and down the Ottauquechee Valley must have been quite as entrancing then as they are now. His brother Charles was the village Squire of my boyhood and youth, respected for his goodness and wisdom. Another brother, Lyndon, was long clerk of the Probate Court, and lived in one of the most engaging of the Elm Street houses.

His father (Charles Marsh, 1765-1849) was a trustee of Dartmouth College from 1809 to 1849, and helped as much as any man ever did' to take it through its days of threatened dissolution and to make it the inevitable forerunner of the larger, but not better, college of to-day.

So much for cows, barefoot boys, and the Squire's farm and the village of George P. Marsh's younger days. Dartmouth students who visit Woodstock will find it worth while to go down Elm Street; cross the iron bridge which long ago replaced the covered "Old Red"; turn to the right—not to the left, for the pasture bars have been gone for fifty years—and up the hill to the Old Marsh Place as reconstructed by Frederick Billings in 1870. I am sure that permission to look out from the verandah upon the landscape setting of the boyhood of Dartmouth's most scholarly of sons will be gladly granted. The low flat-topped stone wall, built in 1874, that curves round toward the bridge was once the finest runway ever known for barefoot boys, and deserves the consideration of even a college student.

III.

Mr. Marsh opened a Phi Be,ta Kappa address at Cambridge in 1847 by saying: "In a youthful people, encamped like ours upon a soil as yet but half wrested from the dominion of unsubdued nature, the necessities of its position demand and reward the unremitted exercise of moral energy and physical force, and forbid the wide diffusion of high and refined intellectual culture."

Here he speaks clearly of his own experience and sets down quite frankly his one desire. He sought all his days for a "high and refined intellectual culture" ; and at 47 had already clearly seen how hard a task it was to gain it in a country of which, he says, in the next paragraph of the same address, that there is in it "no appropriate place, no recognized use, for a purely literary class", and that in it ,the "mere scholar feels that here and now he hath no vocation". The populace still measures our national progress by material gains and "computes our prosperity by the returns of our custom house and the profits of our workshops." All that we learn must be profitably applicable at once, and our schools and1 colleges must lead directly into factories and counting houses. It is seventy-three years since Mr. Marsh said that the conquest of a new land and the building of a new nation were not occupations favorable to scholarship. In those years scholarship and research have here made progress ; but it is doubtful if, in the round hundred years since Marsh's graduation, our own college has been able to develop and maintain an atmosphere more favorable to the student than it was in 1820.

But I find myself, after making a statement like that last, always compelled to modify it. The obvious comment here is that Mr. Marsh was driven by his love of learning, and that his great mental power made a continuing pleasure of the tasks to which his love of learning led him.

He grew up in a remote Vermont village ; spent four years at a college which was a five days' journey by wagon from the nearest city; studied law in his native village; settled down as a lawyer at 25 in Burlington, a small town even more distant from the humanity of our seaboard towns than were Woodstock and Hanover; was in Washington as a State representative from his 43rd to his 48th year; was minister to Turkey at Constantinople, 1849-1854, and ambassador to Italy from 1861 ,to his death in 1882.

That dry outline tells plainly how barren of opportunity for scholarship, rather how void of incentive to scholarship, must have been the greater part of Marsh's life. Add to those bare facts the further fact that though his father was a man of some property, George never enjoyed, either by inheritance or through his own earnings, more than a very modest income, and you will see how great was the obstacle which environment set to the attainment of his dream,—"refined intellectual culture".

I am insistent on the handicap to studentship in America in ,the early 19th century, not that that handicap may serve as an apology for Mr. Marsh's shortcomings in learning, which are not for a casual student like me to find; but to make more prominent by contrast the man's astounding powers and accomplishments. Matthew Arnold met him, in 1865, and said of him that he was "redeemed from Yankeeism by his European residence and culture". Brief as must be the record here given of what he acquired, and of what he gave forth in his. writings, it will amply show that his talents and his industry led him to gain a culture which was far too deep and too broad' to endure any label whatsoever.

IV.

While in college he .bought grammars, the dictionaries for Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, and certain classics in these languages. Latin and Greek he mastered easily, and mathematics as well. While practising law in Burlington it was his habit to have on his reading table a half-dozen books in as many different languages and to pass from one to the other as his fancy or his topic called him. At 48 he writes to Prof. S. F. Baird of the Smithsonian giving him advice on the study of the Dutch language, which "can be learned", he says, "by a Danish and German scholar in a month"! In his book "Man and Nature", 1864, revised and issued in 1874 as "The Earth as Modified by Human Action", the list of works used in its preparation fills eleven pages of fine print, and includes books in ten different languages.

In Constantinople he had a personal library of a thousand volumes. This was in 1850, and1 up to that time the stimulus of human environment toward book acquisition had come almost solely from his native village, from Dartmouth College, from, (Burlington, Vt., and from Washington, D. C.!

At his death his library numbered about 13,000 volumes. It was bought by the same Frederick Billings who had in 1869 acquired from George's brother Charles the old home in Woodstock, and given to the University of Vermont at Burlington, together with a beautiful library building.

This "Marsh library", was catalogued by Mr. Harry Lyman Koopman, now librarian of Brown University. This work gave Mr. Koopman a close and intimate knowledge of Mr. Marsh's studies and achievements, and he writes to me his conclusion that "Mr. Marsh was one of the finest, most commanding figures that ever represented us abroad, a man whose very presence in Europe made America honored." "Dartmouth", he adds "has every reason to keep his memory green".

His wife said of him, writing a few years after his death, that he could speak and write a language as soon as he had learned to read it.

V.

Space does not permit more to be said of Mr. Marsh's talents in the field of language. The wide range of his learning and depth and fullness of his knowledge is shown by his writings and testified to by scholars.

Mr. Koopman published in the Library Journal, December, 1886, a "Trial Bibliography of G. P. Marsh", of about a hundred entries. If each of his many contributions to journals like The Nation and to Encyclopaedias were separately listed the total would be much larger.

Placing these entries in the order of time, we find that he wrote an Icelandic Grammar at 38; a discussion of the influence of the Gothic spirit on New England's founders at 43; made notable contributions to a discussion on the Smithsonian and on libraries as essentials to learning at 47; published a book on the camel at 56; a report on Vermont railways at 58; books on the English language at 60 and 62; and the first edition of Man and Nature at 65. With these more important items appear references to many addresses, reports, essays and contributions to encyclopaedias and journals.

The eagerness of Mr. Rugg of our college library to make as complete as possible that library's collection of the writings of Dartmouth alumni surely makes it possible ,to find in Hanover a good part of Mr. Marsh's works. I am trying, through this article, to persuade a few of my fellow alumni and a few undergraduates to give at least an hour or two to Mr. Marsh's writings. I particularly recommend his "Earth as Modified by Human Action". Donald G. Mitchell says that it contains enough of wise observation, sound reasoning and cumulative knowledge for a half dozen treatises. He is quite right. It is full packed with knowledge and suggestions. In its opening pages he gives an explanation of the fall of the Roman Empire, and no better explanation has yet been set forth. I open it at random, to page 113 and find a discussion, as up-to-date as the latest by our Audubon societies, of the destruction of insects by birds. On page 52 I find in a footnote remarks on the "old legal superstition, fostered by the Dartmouth College Case, as to the sacredness of corporate prerogatives". This antedates by 40 or 50 years the anti-trust movement out of which recent political reformers have acquired so much credit.

On page 11 the author gives us almost a credo. Speaking of the Observation of Nature he says that in this book it is his aim to stimulate, not to satisfy, curiosity; and that it is no part of his object to save his readers the labor of observation or of thought. "For labor is life, and Self is the schoolmaster whose lessons are best worth his wages. For every earnest observer, the power most important to cultivate, and, at the same time, hardest to acquire, is that of seeing what is before him. Sight is a faculty; Seeing an art.

"Next to moral and religious doctrine, I know no more important practical lessons in this earthly life1 of ours thanthose relating to the employment of thesense of vision in the study of nature."

VI.

In books by Mr. Marsh and in books and essays about him, I have marked as worth including in a presentation of his character, his powers, and his writings, passages that would easily twice fill this journal.

I hope that statement will make it quite clear that I have found full of interest and pleasure the task of preparing this, very fragmentary note upon the most scholarly of Dartmouth's sons.

A most casual glance at "Man and Nature" shows that the author was not a linguist and a reader only; but that from his earliest boyhood to his latest day he lived according to his creed,— "Self is the best Schoolmaster", and "Seeing is an Art". Still more emphatic is the testimony, to the same fact given by his letters. Of these his widow published many in the "Life" which she edited. Unfortunately she prepared one volume only of the .two she planned; and that volume ends in 1861, when Mr. Marsh left America to become Ambassador to the new-born Kingdom of Italy. It is a great pity", Mr. Koopman writes to me, ".that Mrs. Marsh's life of her husband was not completed. The second volume would have been still more interesting than the first."

In this first volume, beginning in 1848, we find many letters addressed to Prof. Baird of the Smithsonian. In these letters are countless allusions to scientific subjects, including accounts of collections made and sent to Baird from Constantinople and other places, of fishes, lizards and many other things. From all these notes it is plainly to be seen that Baird the scientist found in Marsh a man of the rare scientific temper. Baird knew that Marsh practised seeing as an art, and found in him one who added to a vast store of learning gleaned from books the learning gained through the observation of nature, with "Self as Master".

VII.

He was seemingly as much at home in the field of art as he was in .that of science. Allusions to art topics are few in his published letters, probably because in his first 48 years he had no correspondent to whom such allusions would be of interest. But he had made, before he left Washington in 1848, a large collection of prints; and for a poor man to have learned .to admire and to wish to own fine prints, early in the 19th century in this country, was to indicate a keen interest in the most refined of all the arts. Good paintings, good sculptures, good examples of decorative art, were all here sadly lacking. In prints they were all portrayed to the mind of a man of taste and learning, and to prints Mr. Marsh turned quite naturally for study and enjoyment. He was almost obliged, by stress of money difficulties, to dispose of his collection in 1848. The Smithsonian purchased them; but unfortunately they were almost destroyed within a few years, first by a fire and later .through indifference and neglect. A report on this collection made by Secretary Jewett of the Smithsonian says that, it was believed to be the choicest collection then in this country. It illustrated the progress of the art of engraving from its early masters to the present time, and contains some of the best works of nearly every engraver of celebrity.

That it is now destroyed is cause enough for grief, only slightly softened by the thought that its brief existence is abundant evidence of Mr. Marsh's zealous interest in and his thorough knowledge of all the arts.

VIII

I have left myself no space to speak of Mr. Marsh's travels. Turkey, Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt, Germany, Italy—in and through them all he made journeys, often under very trying conditions and always after the manner and style of travel in those lands 40 to 70 years ago. Everywhere he observed,—practised the Art of Seeing—wrote voluminous letters to his family and friends at horn?, and made notes. The letters, alas! are nearly all destroyed. The notes he used to a large extent in the writing and the revision of his "Man and Nature".

Nor have I left space to speak of his work as a diplomatist. Here I am driven to quotations, and with them must close. William J. Stillman said in the Nation in 1882, "It has been my fortune to make the acquaintance of many distinguished men, and of all I ever knew, George P. Marsh was the noblest combination, me judice, of the noblest qualities which distinguish men—inflexible honesty, public and private; most intelligent and purest patriotism.; ideality of the highest as to his service in his official career; generosity and self-sacrifice in his personal relations; quick and liberal appreciation of all good in others, and the most singular modesty in all that concerned himself; unfaltering adherence to truth at any cost; an adamantine recognition of duty which knew no deflection from personal motive; and, binding the whole in the noblest and truest of lives, a sincere religious temperament in which the extreme of liberality of others was united to the profoundest humanity as to himself If anybody loved him, it was for the sake of truth and justice he himself so revered; he was so broad in his humanities, so uncompromising in his judgments on his own feelings, so free from vanity of any kind, or ostentation that he seemed almost impersonal."

S. G. Brown said in an address on Mr. Marsh at Hanover, in 1883,—"Mr. Marsh followed the Italian government, of course, in the change of its capital from Turin to Florence and from Florence to Rome. No prime minister was more respected for learning, weight of character and familiarity with affairs, and long before the end of his protracted service, his personal influence with the court had become as efficient as it was wise and beneficent.

"It was greatly to the honor and the advantage of our government, whatever causes may have lead to it, that through all the changes of administrations, and in spite of the clamor for office, he was regained at his post. No foreign diplomatist, however accomplished, could for a moment feel in his society that he was called to associate with one not fully his equal; no man of letters or lover of antiquity, or student of history, or student of nature, or devotee of art, ever interrogated him without an intelligent response; no political philosopher, watchful of national progress, no defender of absolutism, could help honoring a Republic which committed its interests to so learned, so wise, so conciliatory, so faithful an ambassador; and no American traveler or resident could for a moment feel that his personal interests or the interests of the country were not safe in his hands."

Mr. Koopman writes me: "In the Dartmouth book about Daniel Webster you will notice that the writer or speaker refers to the great impressiveness of Webster's presence even when in the same procession with George P. Marsh, —which is indirectly a tribute to Mr. Marsh, for Webster in appearance as well as ability was a superman; so in ability was Mr. Marsh. He was called 'cold' but this was largely due to his contempt for triflers and trivial interests. He was capable of warm friendship as you see from his correspondence with Baird In the very breadth of his interests along with their importance, Mr. Marsh was a splendid representative of the intellectual American of the first half of the 19th century. I know that scholars still greatly respect the work that he did in early English. I have an idea that he is really the father of the great reclamation work that America has done. In diplomacy I presume he would rank with Franklin and Charles Francis Adams as one of our three most distinguished representatives abroad."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue