Following is the text of a letter toPresident Nixon from President Kemenyin response to President Nixon's letterof September 18 sent to more than 900college and university presidents on thesubject of campus unrest.

DEAR MR. PRESIDENT:

Your letter to university presidents reached me belatedly, since it was addressed to my predecessor. I would like to give it the thoughtful answer it deserves.

First of all, let me stipulate that I accept your charge: "the primary responsibility for maintaining a climate of free discussion and inquiry on the college campus rests with the academic community itself." Under the leadership of my distinguished predecessor, John Sloan Dickey, such a climate was maintained on the Dartmouth campus during the past 25 years. I am proud of the record of my institution and will do everything within my power to continue Dartmouth's outstanding record.

A policy of Freedom of Expression and Dissent was drawn up by a faculty-student committee a few years ago. It was approved overwhelmingly by the faculty and endorsed by the Board of Trustees. Every student entering Dartmouth College must signify his acceptance of this policy:

"Dartmouth College prizes and defends the right of free speech and the freedom of the individual to make his own decisions, while at the same time recognizing that such freedom exists in the context of law and of responsibility for one's actions. The exercise of these rights must not deny the same rights to any other individual. The College therefore both fosters and protects the rights of individuals to express dissent. Protest or demonstration shall not be discouraged so long as neither force nor the threat of force is used, and so long as the orderly processes of the College are not deliberately obstructed. Membership in the Dartmouth community carries with it, as a necessary condition, the agreement to honor and abide by this policy."

Thank you for sharing with me the testimony of Professor Sidney Hook before your Commission on Campus Unrest. I know and respect Professor Hook. Many of his suggestions are constructive and useful. Yet I must disagree with one of his fundamental assumptions.

Professor Hook states that: "The objection is not to controversy, for intellectual controversy is the life of the mind. The public objection is to how controversy is carried on—to the use of bombs, arson, vandalism, physical assault and other expressions of violent strife and turmoil." I wish that this assumption were correct, because it would make it much simpler to administer institutions of higher education. Unfortunately, I know from first-hand experience that all too often the objection is to intellectual controversy, no matter what form it takes.

I agree wholeheartedly that violence, assault and all forms of coercion are intolerable on the university campus. However, the vast majority of students do not engage in any such activity. They express concern about the problems of society in a dedicated, responsible and constructive manner. I have therefore been quite disturbed by the high level of intolerance shown by many Americans towards the peaceful expression of unpopular views.

I am greatly concerned over the fact that there is a tendency to lump together the small violent minority with the vast majority of concerned and constructive students. I too have complained on occasion that students tend to be highly impatient, show a lack of understanding of the political process and refuse to recognize the lessons of history. And yet one must recognize, as Professor Hook said, that "intellectual controversy is the life of the mind."

The deep concern of students for the abolition of all wars, the eradication of racial prejudice, the saving of our environment, and the solution of the many perplexing problems of our technological society serves as a cry of conscience for the entire nation. I regret expressions of intolerance towards constructive criticism which, by implication, would deny students the right to express their own ideas. I also regret the many incidents in which students have been coerced or assaulted for a crime no greater than wearing their hair too long or favoring an informal mode of dress. For one who has had to flee persecution in Europe and found a haven in the United States it is a matter of great personal sadness to find such irrational intolerance on the increase.

I would like to thank you for appointing your Commission on Campus Unrest. I feel that the recommondations of the Scranton Commission represent a truly well thought-out, balanced blueprint for solving the problems of the universities. I urge you to give the most serious consideration to the implementation of all their major recommendations.

I am in complete agreement with the Commission's statement that "violence and disorder are the antithesis of democratic processes and cannot be tolerated." But equally important is their statement that "dissent and peaceful protest are a valued part of this nation's way of governing itself." I accept their criticisms of the shortcomings of universities and their constructive recommendations for ways in which we can improve both the system of higher education and the government of our institutions. The call to students to protect the right of all speakers to be heard, and to acquire greater understanding of the processes of change, is most welcome. Equally important is the Commission's recommendation for a change in the national climate that will make it easier for university administrators to carry out their appointed tasks.

In particular I strongly urge you to accept the Commission's recommendation that you use your high office to provide moral leadership for our nation and to create an atmosphere of tolerance and understanding.

I have learned in my brief seven months in office that a special responsibility belongs to the president of the college to try to explain the various segments of our academic community to each other and to bring about understanding and a tolerance for dissenting views. I realize the magic invested in the office that gives the president both a unique opportunity and a heavy responsibility. I am happy to say that we have made major strides in improving understanding amongst our students, faculty and alumni.

This experience leads me to believe that only the President of the United States is in a position to bring about such an atmosphere of tolerance and understanding on the national level. While it is certainly part of your responsibility to point out the sharp distinction between freedom of speech and violent action, I hope that you will be willing to play the leading role in helping the non-academic community to understand the feelings of the vast majority of faculty and students.

We must not allow a very small percentage of extremely radical students and faculty to present a completely unfair and distorted image of the American university. If you could take the initiative to explain to the nation that the vast majority of our faculty and students are deeply and sincerely motivated to work for the improvement of our society through peaceful means, and to recall to our citizens that tolerance for unpopular views is a cornerstone of American democracy, it would go a long way towards healing wounds in our country and reestablishing that atmosphere of tolerance which is crucial for the existence of our universities.

I am happy that you have taken the initiative in opening channels of communication between yourself and those of us who are responsible for higher education in the United States. I hope that this exchange of letters is but the beginning of a continuing dialogue.

Sincerely yours,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is a Conservative?

November 1970 By NORMAN LAZARE '40 -

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

November 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

November 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

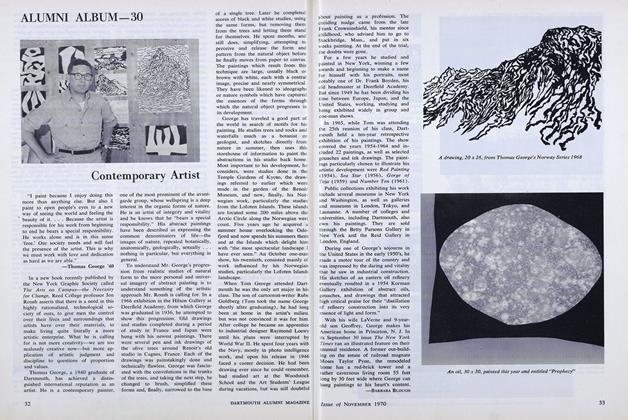

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

November 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Article

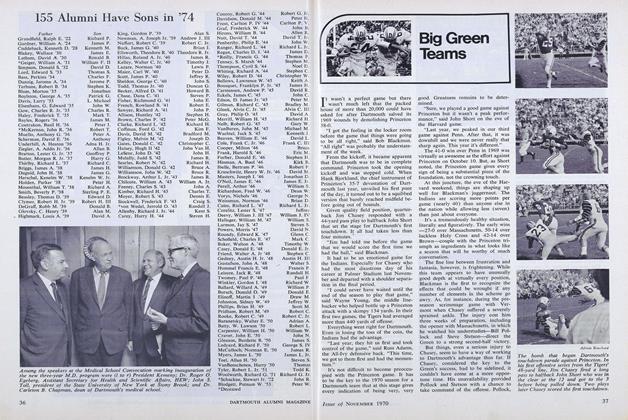

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe ROTC Decision: An Explanation

November 1970 By ARTHUR LUEHRMANN

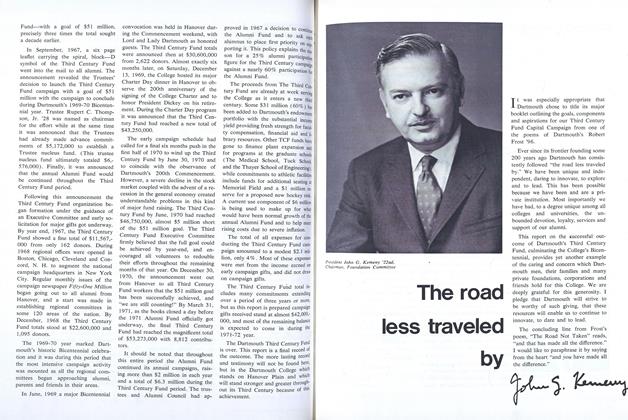

John G. Kemeny

-

Article

ArticleThe road less traveled

DECEMBER 1971 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to '73

JULY 1973 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

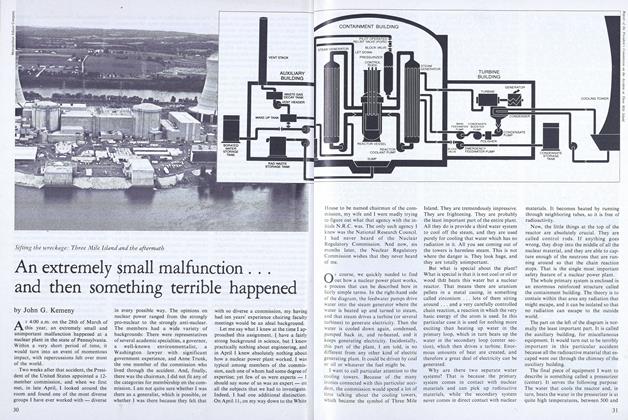

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleA Compressed Life

February 1993 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Valedictories

July 1974 By LAN R. LAW '74, John G. Kemeny

Article

-

Article

ArticleProgram of 29th Annual Winter Carnival

February 1939 -

Article

ArticleTim Ellis Memorial Fund

February 1956 -

Article

ArticleCLASS AGENTS DINNERS

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

ArticleFraternities Should Be Strengthened

MARCH 1992 -

Article

ArticleTough Act

JUNE 1978 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

January 1974 By J. H.