The Grand Strategy of Evolution, The Social Philosophy of a Biologist

February 1921 Wilbur M. UrbanThe Grand Strategy of Evolution, The SocialPhilosophy of a Biologist. By William Patten, Ph. D., Professor of Biology in Dartmouth College.

The normal corrective for the disastrous social effects of extreme specialization in science and education is the study of philosophy. For reasons into which it is not necessary to enter philosophy, in the technical and conventional sense of the word, is scarcely fulfilling its function at the present time. More and more it is becoming evident that the way back to philosophy, for the average man at least, must lie through the special sciences, and must be pointed out by those who, like Professor Patten, driven by the deeper necessities of understanding, leave, for a time at least, the field of investigation for the field of interpretation and apply their wide experience to the solution of the more general problems of their fellow men. Among the growing number of such attempts Professor Patten's new book must be reckoned as' one of the most useful as it is one of the most vigorous and independent. Without undue technicalities, he reveals the deeper meaning of evolution and with helpful common sense applies the elementary principles of nature to the problems of the individual and social life.

Professor Patten is not a philosopher in the ordinary sense of the word. He does not pretend to be. It is as "a purely personal record," the record of "one compelled to act as secretary to his own disordered mind," that he would have his book received. But for that very reason, perhaps, he is the better fitted to act as interpreter to the disordered minds of his contemporaries. When the war revealed the wide-spread influence of false conceptions of Darwinism, he realized that something must be done towards furnishing a better worldview, something that would show the "grand strategy" of evolution in a truer light. The 'vital human interests of church, of science and of state call for a common language, but as he rightly sees, there is only one idea in the common possession of them all, the idea of cosmic evolution. Professor Patten has not exaggerated the central importance of this conception nor the great social need of a sounder popular philosophy. In undertaking to supply this need, in showing that cosmic evolution is a continuous triumph of constructive over destructive agencies, of cooperation over competition, of peace over war, Professor Patten has done yeoman's service, not only for the cause of true science and philosophy, but for the deeper human interests of morals and religion.

Professor Patten begins his story of cosmic evolution by showing how there is present, even in the inorganic world of atoms, processes of what he calls "constructive Tightness," identical with those we call moral in the life of man. Progressive cooperation, organization, service and discipline are viewed by him as inherent properties of matter and life. In short, co-operation, not competition, is seen to be the creative process common to all phases of evolution, inorganic and organic, mental and social. Physicists who still hold a dogmatic and uncritical view of their concepts of matter and motion will doubtless take exception to this new form of "animism." Biologists will miss the discussion of many special questions such as the origin of life or of vitalism vs. mechanism, the solution of which they will feel is bound up with the larger problem. Psychologists and sociologists will have their caveats to register and critical philosophers will perhaps feel that this is but another of the many uncritical monisms that they find themselves called upon to demolish. But all will be carried along by the tremendous sweep of the story, by the panorama-like vividness with which the onward march of the creative forces of evolution is portrayed, and they will have much to learn from this vigorous essay in interpretation, with its robust conviction of moral forces at the very heart of things. If, as the author himself suggests, they will lay aside their own particular prejudices, coming foot-free with him over neglected trails, "they, too, may see that elemental truth which governs the institutions of nature and man alike. The right to exist and the obligation to serve are one and inseperable; for to exist is to give, and to give is to receive."

From this emphasis upon the larger social and philosophical implications of the book it would be a mistake to infer that the knowledge and power of the specialist is not evident on every page. One of Professor Patten's lifelong preoccupations with the world of living things could scarcely fail to reveal the most intimate acquaintance with biological lore. As an authority on the evolution of the vertebrates', it was to be expected that his chapters on the "Great Highway of Evolution" would be a masterpiece of biological exposition. Speculative originality is present also, as when he extends the concept of tropisms in the lower vital world to the higher reactions of man. But after all, the significant thing is that he has ventured to put his matured scientific wisdom at the service of the larger spiritual interests of men, and that this matured wisdom has brought him, although in has own way, back to the eternal verities. For him all the constructive problems of social life reduce themselves to the problem of ways and means of extending the principles of cooperative action to larger and larger groups and for longer periods of time. Labor and capital, science and religion, must draw together in mutual give and take and, since human evolution is "a progress towards a world-wide co-operative life," a true internationalism is its necessary goal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhat does a man lose by going to college ?

February 1921 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

February 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT, '72 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleTHE LOG OF THE DARTMOUTH OUTING CLUB

February 1921 By LELAND GRIGGS '02 -

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH PIONEER

February 1921

Wilbur M. Urban

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

April 1946 -

Books

BooksCHRISTIANITY AND THE FAMILY.

January 1945 By Amdrew G. Truxal. -

Books

BooksZEHN JAHRZEHNTE 1860-1960.

December 1959 By HERBERT R. SENSENIG '28 -

Books

BooksWORKSHOPS FOR THE WORLD.

February 1955 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN INDIAN: A RISING ETHNIC FORCE.

May 1974 By MICHAEL A. DORRIS -

Books

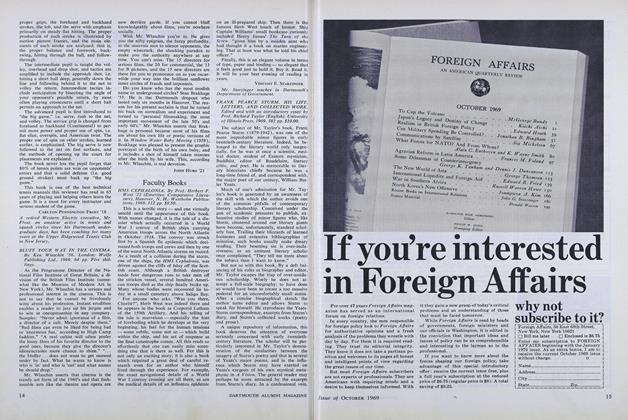

BooksHMS CEPHALONIA.

OCTOBER 1969 By VINCENT E. STARZINGER