From Long-Hand and Probably Inaccurate Notes

Wasn't it just too funny, Mr. Editor? I read that'story about Cuthbert Payson his diary, I mean—and you can judge of my surprise, and grandma's too, when I told her; for she doesn't know so much now about college things as I do. She didn't go to college, but my goodness! she says it was worse than if she did, because she grew up in a college town-right in Hanover; and what the faculty didn't know the women folks did; and what the women didn't know—the "sassiety" ones, I mean—the maids, the help, knew; and what they didn't either of them know they made up; and so after a while the girls knew it all. Grandma says if they think all that stuff is worth printing they might ask her and she could tell them a few items that haven't reached the public, at that.

She says that grandpa never told her a word about any old diary, and the idea of his writing all that foolishness about Miranda and Tottie and the rest and never saying a word about her is perfectly ridiculous. She was just seventeen years old when he graduated, and he kept his eye on her for five years and then he married her. And she says that was very unusual, because-even if they went away engaged—and they'd get engaged gaged in the strangest places; propinquity, you know—they generally forgot all about it, and so did most of the girls, and started over.

Golly, aren't I the little bonehead! I haven't told you what the joke is. Cuth bert Payson was my grandfather. That makes him grandma's husband, doesn't it? Her father was the well known professor H. I. Story. And grandpa Cuth didn't say anything about that either, did he? I wonder if he always passed his examinations like the time he told about in his diary. Just think! Grandma knew Bill Kent and Jack Eastern and Fat Enderby, because they all came to the house. Her mother didn't let her see much of the students because she was such a kid; but she knew all that was going, and a lot more students than her folks thought; though she never had anything to do with the fellows that whistled when the girls went by the houses where they roomed.

The first time she really noticed Cuth bert was one day when ''just for greens" as they said, two or three of them came to visit the Home School for Girls, and the head teacher was wise, and got them to move the piano (and she had to hire four men the next day to move it back.). Grandpa was a splendid big strong fellow. Every one except the faculty knew that they never could have got the cow up into Bed Bug Alley (She says no girls ever used, those words in her time) if it hadn't been for Cuth. But they wouldn't have told under torture. Well, anyway, they wouldn't be bluffed, and so they tackled the piano; and Cuth pretty nearly carried the whole of one end. He didn't have on his important clothes, if he had any; and grandma thinks he had on an old collar or something; anyway it broke loose and he couldn't fasten it again with out undressing, and he looked so red and absurd that the girls all giggled. But grandma says that even with a mackintosh face and a punctured collar he was a knock-out, and the moment she set eyes on him she fell for him right off. Anyway that was what she meant. Maybe she said some old stuff like "mash" or "crush". Of course the girls didn't dare do a thing; but she went and got old aunty Benson to fix him up.

After that she sort of managed to get around where he'd notice her, the way girls do. She says she almost blushes now to think of it. And they had a little handkerchief flirtation, all perfectly proper because they had been introduced. I don't know the silly stuff, but you wave it up and down and back and forth and draw it across your lips and put it in your pocket with your left hand and so forth, and it is all supposed to mean something. (She needn't talk to me about modern flappers.) When Commencement came she went and got a big bunch of roses out of the garden and sent it up by the usher without any card. But Cuth told the usher he'd punch his head if he didn't come clean. And of course the usher gave it away like they always do. And grandma begged so hard to go to the reception or levee or whatever they called it that her father and mother took her with them. And she had two promenades and one lemonade with grandpa. Wouldn't that cause a smile? And he gave her a knockdown to two or three other of the big snakes. But she was all sold out to Cuthbert the more she saw of the others.

After that he used to make a point of coming to Hanover as often as he could; and he used to jolly Mrs. Frary and tell her that he was making a bluff of coming to Hanover on business, but really he came to get some of her meat pie. All she'd say was "huh". But one time when he was going away she said with a kind of twinkle that there'd be some more meat pie in just three months, and if she saw anyone meddling with his business she'd let him know. She really liked him even if he did have an awful mean appetite. She was a good scout, and they had her to the wedding when it came. Grandpa didn't have any money at all, but he told her that if she'd just wait he'd get some all right. She said she'd wait till she was old and gray, till she was thirty anyway. She grew prettier and prettier, (Grandpa told me that) but she didn't pay much attention to the fellows that tried to rush her, just enough to keep alive and they used to call her "Mystery"; the old prof was "History," from his initials you know. Wasn't that a scream ?

I guess girls aren't so awfully different then and now. I could add a few neat observations on the Johnny complex myself, only—this isn't my story.

You know Mr. Editor, I went to the Carnival. They sent around such a funny notice about being warm and comfortable. Maybe they thought we'd be wearing galoshes and sweaters and things if they hadn't been the style. I don't guess so. But I had just the cutest knickers you ever saw. And I'm thankful to say that the fellows don't grab hold of your arm and tow you around in broad daylight like we were blind babies that couldn't walk alone. I had a perfectly gorgeous time, I danced with the captain of the football team and the manager of the dramatic club; and as Wilfred was in the Show he got a perfectly splendid fellow that writes for The Dartmouth and some of the papers to take me. He is so delightfully sarcastic and has such a cute way of stroking his chin just before he says some perfectly withering things. They got one joke on me. At the tea dance at the Eta Pi House they sold me such a nice handsome high-talking fellow that I was quite struck. I thought he was a perfect gentleman, but do you know he was just one of the kid faculty. How they gave me the merry ha ha!

Grandma says "What a goose you are! Can't you, after going almost through college yourself, find anything better to talk about than those young snips?" I said kind of gentle, for she is a good old thing, "What did you use to talk about, Grandma?" She spoke right up, "You needn't think that these young fellows with their good clothes that papa paid for and their glued hair and their lazy know-it-all ways are like the men we knew when I was a girl." And then she gave a great big sigh. So I just said, "How long did it take them to get into the war, when they found out about "it?"

They are the best we've got, anyway.

I had some fun shocking grandma, at that. Now I'm no wise guy to put it into words, but it seems to me that people who think the same way that it is just horrid to be really bad get into a peck of trouble over things that don't themselves do any harm. See? Like this,—grandma used to think it just awful if her ankles showed; at least the old dames told her so when she was young. Ankles! You can't possibly make anything wicked out of ankles. The bicycle got rid of that anyway. Grandma knows I wouldn't do anything I really thought was wrong, but when she sees me in my knickers she holds up her hands in horror and says "my che-ild !my che-ild!" I expect she would pass away if she saw me in my one-piece bathing suit. But do you know I never think anything about it. Knickers are such a blessed deliverance from skirts when I am in the woods or the snow; and if a one-piece bathing suit isn't just the thing to swim in I'd like to know what is, except the skin; and maybe that is going a little far in a cold climate. Are men indecent in their running clothes,—when they are clean?

Well, I got switched off what I was going to say. You know the mean old faculty turn us out of the frat houses on Sunday, so a lot of us went over to the Lignumberg Inn. They wouldn't let us dance till the clock struck twelve; the Puritans aren't all dead yet. So to kill time there were some little petting parties in the small rooms. Nothing much. No twos-ing, you know. When I mentioned it to Grandma she asked, "What in the world are those?" And when I explained she almost fainted. "Great Heavens! Goodness Gracious! Why Joan Payson," said she. (I don't see why it is any worse to go the other way and say "Hell and damnation", and things like that.) "I should worry", said I; "I wasn't in it." And that gave her another chance. "How can you use such senseless vulgar expressions? If you are going to talk that way you ought to have some gum." (Wasn't that cute of the old dear?) Then I got back at her real catty. "Now grandma," I said, "didn't you use to say, 'I should smile', and 'I should gurgle', and 'I should relax my features', and 'I should blush to murmur'? And didn't you think it was awful funny when the boys used to say to each other, 'Wipe off your chin', and 'Pull down your vest'? And when you wanted to be real tough didn't you say, 'O bother the old thing', and 'Drat it' ? I'll bet you've said 'Darn it' in your day. And when you wanted to be a regular cut-up didn't you use to sing 'Coca chelunk chelunk chelaly,' or 'The waiter roared it through the hall, We don't give bread with one fish ball'? Didn't you? And how about sliding down the hill on those bob-sleds with the boys holding up your legs with white stockings on? Was that the road to perdition?" I just wanted to stampede her, for I wasn't quite so sure about those petting parties myself; and I did.

She tried to bluff, but she couldn't. Then when I had her all fussed up I took pity on her, and I said, "Never mind, Grandma; I'll forgive you. I never thought you were a bad person" (She is a regular old dear.) "Now tell me about the college ages and ages ago. Were the fellows so awfully different? And was grandpa Cuth the smarty he makes out in that diary?" "Well", she said, "I don't know much about them now, only what you tell me. They don't invite me to their carnivals. But I guess they are different. Things are a lot easier for them now, and that makes everything a little different. There aren't any better or smarter fellows than when I was a girl. But whiskers and tall hats was the best they could do; now they have telephones and automobiles, and pay eighty or ninety dollars for just one suit of clothes. I guess grandpa's set could have swapped with them there and come out all right. But they were a great deal poorer then, and more serious; they had fewer interests and those were nearby; they didn't have all these games and things so they had to have some mischief for amusement. They spread out pretty thin now from what I hear. I know they dress better, keep their hair cut better, act more polite; they are brought up different, waited on more, and spanking has gone out of fashion. They tell me that only a little more than half those that start go through college, mostly because they want to do something else. It wasn't that way when I was a girl. Most all of them stuck to it and graduated unless they were sick or their money gave out."

Grandma stopped and counted her stitches. I expect she got to thinking of the old wayback times. "Grandma", 1 said to start her off again, "Grandpa muSt have been quite a singer when he was young." Grandma laughed till she had to lay down her needles and wipe her eyes. "Sing"! she said; "he couldn't sing the doxology in long meter and keep the key. They must have been awful patient to let him go to that Choral Society he writes about. I guess they just liked to have him around. The only time he ever tried to sing was when he was taking his bath, and I guess it would have kept the animals away. He had two tunes, songs, I mean, 'Shoo fly, don't bodder me,' and 'l'm Captain Jenks of the horse marines; I feed my horse on corn and beans. of course it's quite beyond my means; A captain in the army.' And he sang them as far off the key as it is from New York to Hanover in the winter. Why, one day one of the neighbors wanted to know why they tooted the horn in our garage so early in the morning."

Grandma wiped away something that looked like a tear. "He could make others sing though. One time an Uncle Tom's Cabin play came around, and of course we went to see it, even lots of the church members. Maybe you've seen it. At the end was a kind of panorama moving up instead of sideways as they generally do. They called it the 'Apotheosis of Little Eva.' When it came Cuthbert got up and said, 'Now fellows'; and then they sang together, 'Empty is the cradle; baby's gone'. After that some of the wicked ones started 'Nearer my God to Thee', but I'll say for Cuthbert that he hushed that up right away."

"He was a regular cut-up, wasn't he?" I said.

"He was full of fun, if that's what you are talking about," said grandma sternly; "but he wasn't mean about it. He didn't steal the ice-cream that they carelessly left outside the kitchen door the night of the Junior party at Prof. Watts'. He didn't lock Prof. Phussey into his recitation room, though it looks so in his diary. It was Bill Kent. And you could trust him not to take any of the well—intimate garments—off a clothesline in the night; and you couldn't trust some of them, I'll tell you. He did have a hand in carrying off freshman Guffy so that he couldn't go to his class supper and make a speech about Cuthbert's class. But they • didn't hurt him any, and they gave him better food than he ever knew there was after boarding at one of those two-and-a-half-without-tea-or-coffee-clubs. They said he fired off the gun in Prof. Neanderthal's recitation; but he didn't. I guess it is safe to tell now that it was that Fat Ender by. Did you ever! Coming to our house just as innocent, and keeping on probation pretty much all the way through college! I suppose your grandfather did start going to examination with a big drum and wearing crape on the left arm. And he carried the cane the first rush his class had with the sophomores. There wasn't any harm in those things, except that they irritated the faculty; and I suppose that's what the faculty are for; partly, anyway. O, I could go on for a week." And she started for her knitting which she had actually forgotten while she was talking.

"Spill it, grandma", I said; "shoot".

"What", said she, with a kind of jump.

"I said 'please continue; your reminiscences interest me beyond measure.' "

Grandma looked at me severely and uttered these words, "Joan Payson, you are talking through your hat." Now waddo you know about that?

"Do tell me some more, Grandma. Did they treat the faculty with more respect than they do now." I didn't care, but I wanted to keep her talking.

"I don't know. They always touched their caps on the street and stood up when the profs came into the recitation rooms, and that is something; but I guess they were always saying—some of them—the same as they do now, that the profs couldn't get their living any other way. lit took them a good while to understand what that prof in another college said, 'I don't want to take it all in money'; but I guess a lot of them do understand as they grow older. They had their trials besides worrying over nice fellows that just wouldn't study. You see they always talked them over in faculty meeting then; so they felt better acquainted. I guess the faculty that deserved respect got it then, and probably do now. You couldn't respect every one.. I know father never dreamed that he wasn't getting all the respect there was.

"But they had queer trials with some of those awful green students. I don't suppose there are any now. There was Marcus Henneberry. He was very poor, and father asked him to come and see us. He came that same night as soon as he had eaten his supper,—about quarter past six. Father and mother hurried through their supper and went into the parlor. Marcus said he'd come, as long as father asked him to; and that was all he had to say. They put him through the usual questions,—where he roomed, and where he boarded, and how he liked his studies, and which was the hardest, and which prof he liked the best, and what he was going to do when he got out of college. He was boarding himself, and that touched mother; so she went out and got a big cut of Washington pie—real hearty stuff—and asked him if he liked it. Hie tried it and then he said he did. About eight o'clock mother got out the album, and then father took his turn with photographs of ruins they had just dug up somewhere. At nine mother had to go and see Maria about breakfast and didn't come back. I don't know just how father got along; he wasn't much of an entertainer without mother. When the college clock struck ten Marcus said he guessed he'd better be going. And there is where father made a mistake; he was always polite, and he said, "Must you go now?" Generally they said they had to go and study, and that was a good enough reason for a prof; but Marcus said 'No I don't have to; I've got my eight o'clock lesson'. So he sat down again. At half past ten father asked Marcus to excuse him while he put some wood in the furnace; and when he came back Marcus was waiting just as patient, half asleep. The clock struck eleven as loud as it could, and Marcus jumped up and said he really must go now or he would sleep over chapel, because he generally went to bed at nine. Poor father! He was writing a paper for the Northern Academy on the recent excavations in the Roman Forum.

"And I remember the next night, when father was sitting up late to make up time, a half a dozen of them on the steps across the street began to sing 'Old Dog Tray'; and sang it for just an hour. You know how it goes, 'Old Dog Tray ever faithful grief cannot drive him away he's gentle and he's kind and you'll never never find a better friend than Old Dog Tray ever faithful grief cannot drive him away he's gentle and he's kind ' And that's the way it goes on forever and ever. It's enough to drive one crazy hoping it will stop, even if their voices are good. And something was the matter with their voices that night."

I popped in to show her I was listening, "Well, you did have your trials, Grandma."

"O, yes we thought so; but they don't seem much now. But you ought to have heard the Handel Society fellows sing 'Stars of the Summer Night'. They serenaded me once when I was older."

"But we had our laughs too; only it wouldn't do to let them know it. This is one that went around, and I know it's true. Mrs. Prof. Horatio Jedd was a real good woman, but she was the greatest talker in Hanover. One night she had in a senior to supper, the son of an old friend that sold her eggs and chickens and butter ever since she lived in Hanover. She just about talked him blind, and if he had eaten everything she tried to make him he'd have burst then and there. She couldn't bear to have any food go off the table, and she'd always say 'There's plenty more in the kitchen'. She was bound he should have his third cup of tea, and she asked and she coaxed and she urged. Every time, he said, 'No marm, thank you', polite but firm. For the last call she said in her sweetest tones, 'Now do let me pour you another cup; please do.' And he said, 'Well, marm, you can pour it out if you want to, but I won't drink it'. That settled her; but someway it got out.

"One of them asked mother if she remembered President Wheelock. He died, you know about forty years before she was born. We thought .the joke was on him; but I don't know."

Grandma is some talker when she gets going, is nt she ? But she sat quiet a while, and when she isn't talking her thoughts are going back to grandpa. I guess she thought a lot of him. By and by she said softly, "Did you know that grandpa wrote poetry?" "Poetry!" said I; "you're kidding; he didn't even write his own checks." "But he did. He was real sentimental about the old college days." Then she toddled off into her bedroom and I had to laugh, she's such a precious old goose. Pretty soon she came back with an old portfolio and fished this out. I think I'll let you have it and duck before you read it. Ain't it the limit!

*Famous Bedbug Alley

'Twas in the days when boys were bold, And made their midnight sally, That things waxed hot and froze up cold In famous Bedbug Alley.

The tramp of armies there was heard. Their forces in a rally, And roistering calls the red blood stirred In famous Bedbug Alley.

The Delta Kaps are on rampage And there's no dilly dally They think they only have the stage In famous Bedbug Alley.

But Sigma Eps await the charge, Up coming from the valley With fisty weapons small and large To famous Bedbug Alley.

A sudden hush falls o'er the scene. Who's that that's keeping tally?

'Tis Prexy, slipped the foes between, In dusty Bedbug Alley.

The forces, left and right, divide; Each party starts the ballet And waltzes in a gliding stride From famous Bedbug Alley.

*Contributed. The author wishes to blush unseen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

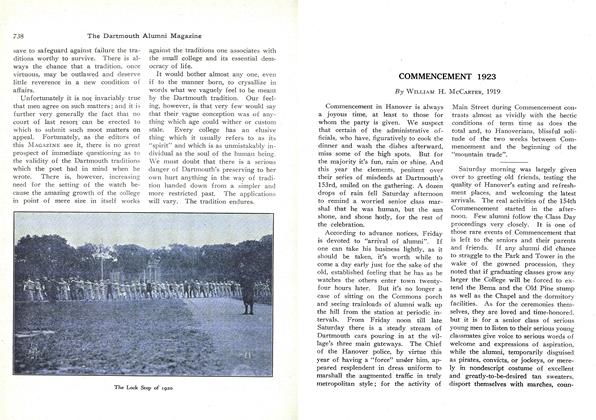

ArticleCommencement is over. The college year is ended.

August 1923 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1923

August 1923 By WILLIAM H. MCCARTER, 1919 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE STUDENTS AND THE AVERAGE AGE

August 1923 By RICHARD WELLINGTON HUSBAND -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1923 By P.E. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1923 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

August 1923

EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72

-

Article

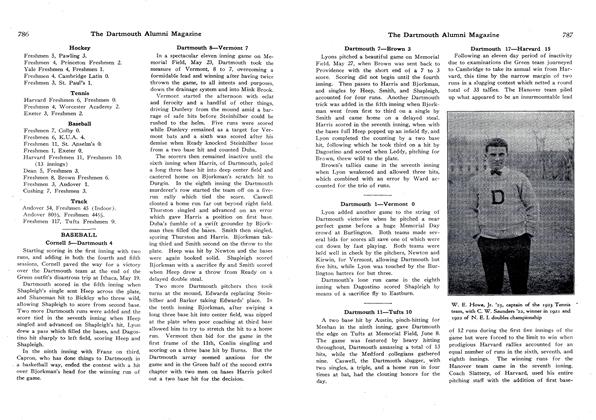

ArticleATHLETIC SPORTS AT DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1905 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE STUDENTS' ARMY TRAINING CORPS OF 1918

February 1919 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

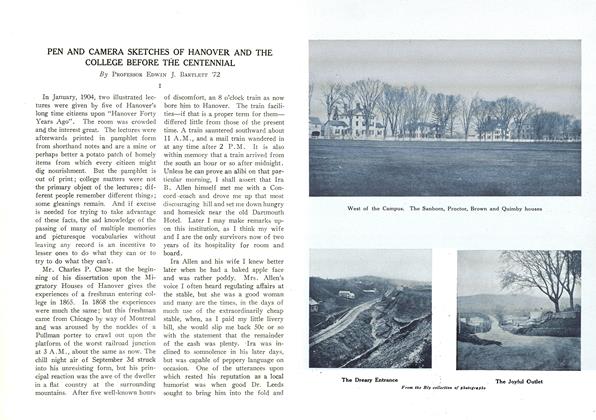

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72