The following sketch of Mr. Kimball of the class of 1854 appeared recently in TheBoston Herald. It is one of a series by Mr. Powers.

It frequently has been asserted, and it is probably true, that our ablest men do not enter public life. This applies more to this country than to England, and it also applies more to the present day than to the earlier history of the Republic. We are living in a material age, in which the desire to accumulate wealth has been on the increase for many years past. Men are not as ambitious to enter the field of politics as in the days gone by. They prefer wealth to fame. It does not require exceptional ability to secure fame in the field of politics. I have known many instances where a member of Congress has become famous by presenting a bill which he had not prepared or even read and which later on became a law, and was christened with the name of the member who presented it, and conferred upon him immortal fame. The name of "Volstead" will be known to our children's children, and yet I do not assume that Mr. Volstead had anything whatever to do with the preparation of the bill at the time it was filed with the clerk of the House. It was, however, reported out of a committee of which he was chairman, that position coming to him by reason of length of service upon the judiciary committee. A legislative assembly affords an immense opportunity to secure popular reputation. Senator Hoar once told me that he did not care whether his colleagues in the Senate listened to his speeches or not, that he was speaking not to them, but to the American people, and if he happened to make a notable speech, he was talking, not only to his own countrymen, but even to people across the seas.

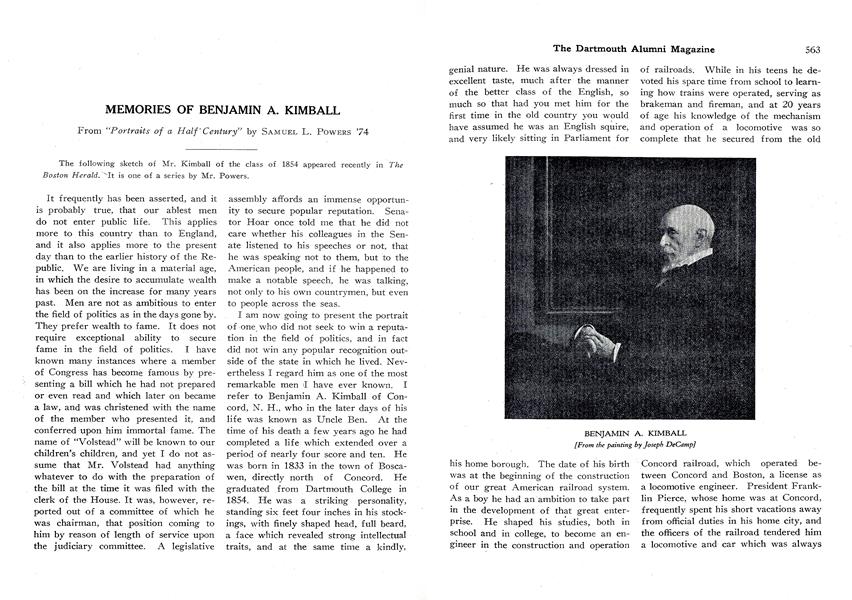

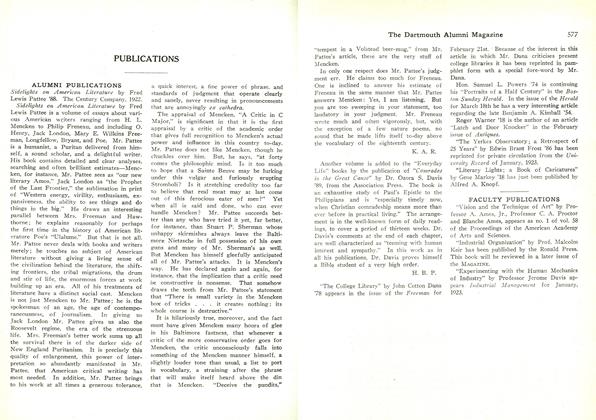

I am now going to present the portrait of one who did not seek to win a reputation in the field of politics, and in fact did not win any popular recognition outside of the state in which he lived. Nevertheless I regard him as one of the most remarkable men I have ever known. I refer to Benjamin A. Kimball of Concord, N.H., who in the later days of his life was known as Uncle Ben. At the time of his death a few years ago he had completed a life which extended over a period of nearly four score and ten. He was born in 1833 in the town of Boscawen, directly north of Concord. He graduated from Dartmouth College in 1854. He was a striking personality, standing six feet four inches in his stockings, with finely shaped head, full beard, a face which revealed strong intellectual traits, and at the same time a kindly, genial nature. He was always dressed in excellent taste, much after the manner of the better class of the English, so much so that had you met him for the first time in the old country you would have assumed he was an English squire, and very likely sitting in Parliament for his home borough. The date of his birth was at the beginning of the construction of our great American railroad system. As a boy he had an ambition to take part in the development of that great enterprise. He shaped his studies, both in school and in college, to become an engineer in the construction and operation of railroads. While in his teens he devoted his spare time from school to learning how trains were operated, serving as brakeman and fireman, and at 20 years of age his knowledge of the mechanism and operation of a locomotive was so complete that he secured from the old Concord railroad, which operated between Concord and Boston, a license as a locomotive engineer. President Franklin Pierce, whose home was at Concord, frequently spent his short vacations away from official duties in his home city, and the officers of the railroad tendered him a locomotive and car which was always at his service when he was at Concord. One day when the President requested his train to make a trip to Boston young Kimball was assigned as engineer to take charge of the, train. When the train arrived in Boston the President came to the cab, shook hands with Kimball and his fireman, thanked them for the safe journey, and asked young Kimball his name and age. It has been popularly assumed that President Roosevelt was the first president to shake hands with an engineer, but President Pierce apparently established that custom nearly fifty years before the administration of Roosevelt. A few days after this trip to Boston the superintendent of the railroad received a letter from President Pierce requesting that young Mr. Kimball be assigned whenever he was available to take charge of his train. Mr. Kimball once told me that this incident was one of the great delights of his life.

His keen intellect, far-reaching sagacity and indomitable perseverance would have won for him distinction in any field of action. He was the best judge of human nature I have ever known. He could read character, analyze motives, and predict future events with marvelous accuracy. During his long life he built and managed railroads, established and operated industrial plants with marked ability. The field of service, however, in which he applied his energy was a limited one, and I have always believed that had Mr. Kimball in early life located in New York, Boston, or some large center of population he would have become a conspicuous leader in our industrial life. However, his love for his native state was so intense that he was quite content to live and die almost in sight of his birthplace and boyhood home. For some 25 years he was a trustee of Dartmouth College, and rendered service of the greatest value in the building up of what Dr. Tucker terms "the New Dartmouth."

During his long life he was a great traveler. Every journey he made was of educational value to him, because he studied the customs and the manners of the peoples whom he visited. Many years ago while he was making a journey around the world he reached Cairo and made the trip up the Nile. While on the boat he was taken ill, and he made a landing at an English hotel located on an island in the river, and before the night was over he was stricken with pneumonia. Mrs. Kimball became exceedingly alarmed. She was not quite satisfied with the hotel physician, and she learned that Sir James MacKenzie, at that time physician to Queen Victoria, was sojourning at the hotel, and she requested the attending physician to call Sir James into conference. This he declined to do, saying that it would be highly improper to make that request; that Sir James was taking his vacation, and under no circumstances would it be proper to ask him to take part in any professional duty. Mrs. Kimball's anxiety was such that she decided to have a conference with Sir James. She told him that she was an American, that her husband was seriously ill, and that she was in great distress, and Sir James said, "I will do everything I can to relieve him," and he took charge of Uncle Ben, and remained with him day and night throughout his illness, staying in the room almost constantly. When Mr. Kimball was convalescing, Sir James said to him, "You are the toughest old fellow I have ever seen. The amount of medicine I have given you would have killed at least ten Englishmen. I have secured from my attendance upon you some very valuable information by reason of the tests I have made, which I would never have made upon one of my own countrymen. They will be of great value to me in the years to come." Mr. Kimball told me of an interesting incident that occurred during his illness. He said at times he was more or less delirious. One night he awoke, and looking through the dim light of the room he saw something in a chair which he thought was a dog, and he called out, "What is that I see in yonder chair? Is it a dog?" Sir James sprang up from his doze, and replied, "Yes, it is a dog; it is your own faithful dog watching by your bedside." Uncle Ben said, as he thought of the unselfish devotion of this great physician, who was willing to give up the much needed rest of a vacation to devote his time and go without sleep in behalf of one who was a stranger and a citizen of another country, his eyes filled with tears, and his love went out to his great benefactor. From that time on Sir James MacKenzie and Mr. Kimball became close and intimate friends. I have seen letters which the distinguished English physician wrote to Uncle Ben, in which he said, "When you next come to London, if you do not come directly to my house I will never forgive you," and it was through that acquaintance that Mr. Kimball came to know a very large number of distinguished Englishmen.

There is one other incident in the life of Mr. Kimball that to me has always seemed exceedingly interesting. Many years ago Mr. Kimball made his first trip up the German Rhine. As he sat upon the steamer's deck viewing the vine-clad slopes on either side of the river, he finally came into view of the castles built by the barons of the middle ages and located on the highest parts of the land on either side of the river. It was then that the thought came to him that he would like to build a castle similar to those, upon a promontory which he owned on the southerly bank of Lake Winnepesaukee; and so he made a landing, secured an architect, and arranged with him to make plans for a castle which suited his fancy. Later on he reproduced that castle, which stands today some 700 feet above the waters of Winnepesaukee lake, on the southerly shore, and which is known as "Kimball's Castle." That castle is an exact reproduction of the one that he selected upon the banks of the Rhine. My belief is that the most joyous hours of his life were those spent during the summer season at this New Hampshire castle. I have seen Uncle Ben many times sitting in a large chair upon the broad veranda looking out through the arches at the view before him, and on one occasion he said to me, "Where in the world can you find a more superb view, one that has greater diversity of scenery, than the one which lies before us?" And it was a remarkable view — 700 feet below were the sparkling waters of Winnepesaukee, dotted with its hundreds of islands, each rich with summer verdure extending to the very water's edge, and farther to the north were the silvery waters of Lake Asquam, hedged in by that beautiful range of mountains — Chocorua, Passaconaway, Whiteface and Sandwich Dome — and then still farther to the north the Presidential range — Mount Washington in bold relief piercing the fleecy clouds; farther to the west, Lafayette and Lincoln and Moosilauke, and still farther to the west the mountains of Vermont, while to the east beyond Ossipee, were the mountains on the westerly line of Maine, and to the south Belknap and Gunstock, as though keeping guard over the castle. Upon that broad veranda Uncle Ben would not only discuss the beauty of the scene, but his breast swelled with pride as he recounted the history of New Hampshire, and the history of Old Dartmouth.

Mr. Kimball was the typical New Englander of the older school. He was a conservative and not a modern progressive. He was opposed to the enactment of a multiplicity of restrictive laws. He favored the greatest liberty for the in- dividual consistent with the safety of society. He believed that the public school was the great agency for the development of good citizens. He was an optimist as to the future of the republic. He was accustomed to say, "Educate the masses and the country will be safe." He belonged to that remarkable generation that has nearly disappeared—brave men and strong, earnest in action, loyal and devoted to country and mankind.

BENJAMIN A. KIMBALL [From the painting by Joseph DeCamp]

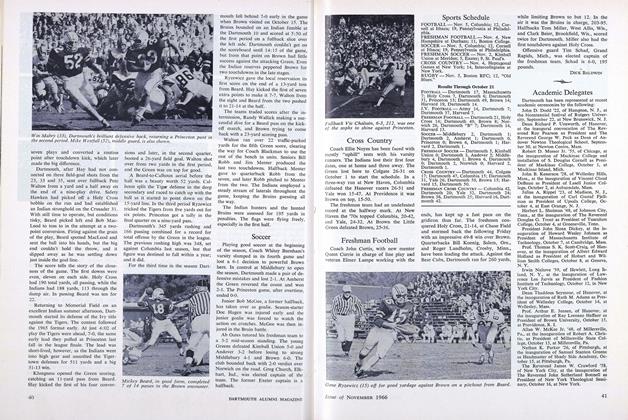

Spring Practice on the Campus

From "Portraits of a Half' Century" by SAMUEL L. POWERS '74

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleReaders of this MAGAZINE will have discovered no doubt

May 1923 -

Article

ArticleRAMBLING THOUGHTS OF A CLASS SECRETARY

May 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

May 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

May 1923 By John H. Chipman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1923 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Books

BooksSidelights on American Literature

May 1923